Facing another election year, American Christians are bound to feel depleted. When Jimmy Carter, a born-again, Sunday-school-teaching Baptist, was elected President, many people thought his Christian sincerity would inevitably make a moral impact. When the Moral Majority was founded in 1979, change seemed relatively simple—just get the great silent majority organized. When the conservative Congress of 1994 swept into office, backed by an enthusiastic corps of Christian activists, many thought the real revolution had begun. Now Christian activists are debating the viability of the Religious Right, with former heavyweight activist Paul Weyrich writing that

"politics itself has failed."

Now we know: Christian influence is not going to be easy. Will we ever see the end of hundreds of thousands of abortions? Will we ever see marriage and sexual fidelity restored to honor? Will entertainment ever again be decent? Will gambling ever be pushed back into the shadows? The uncertainty is discouraging.

Still, this is not the first time American Christians have been discouraged in trying to usher in a moral agenda through politics. Our forebears have much to teach us.

A Vocal Moral Minority

For the past several years, in doing research for a novel, I have lived mentally in an America before the automobile, before the electric light, before modern instruments of communication. Yet I have heard the same sighs of exasperation and discouragement from Christian activists as we hear today. These were the men and women who set out to oppose slavery.

Some of the issues they confronted have eerie parallels in our own day. The political establishment charged that their moralistic crusade against slavery stirred up hatred and violence. (Slaveholders claimed that abolitionism, not slavery, caused Nat Turner to lead his bloody slave rebellion.) The two political parties (Whig and Democratic) contended that they could not take a stand on slavery—or even discuss it—because they must remain a "big tent" to include people of different persuasions. For about 30 years, from 1830 to the beginning of the Civil War, abolitionists gave their lives to a cause that saw no visible success. True, anti-slavery sentiment grew from a tiny splinter of opinion to a vague and uncommitted majority opinion in the North, but not one slave was freed by law, and slaveholders grew harder, if anything, in their resistance. As a result, abolitionists were often discouraged, and some lost faith in the movement and in God.

"The great body of Abolitionists seem to be mere passengers on a pleasure sail," staunch abolitionist Theodore Weld complained to his friend Gerrit Smith in 1839. Another friend, Charles Stuart, wrote to Weld in 1843,

"The Anti Slavery heart of the nation wants re-rousing, and we can obtain no adequate means of re-rousing it. … So that I should despair were it not that 'The Lord reigns' and bids 'the Earth rejoice.'"

Eventually Weld gave up the cause, having decided that he had tried to change hearts in the wrong way and must simply tend to his own. He had been "the most mobbed man in America," a fearless, charismatic speaker who converted whole towns to the anti-slavery cause despite violent resistance. For a generation of abolitionists he was the model of Christian commitment, but businessman and abolitionist leader Lewis Tappan wrote sarcastically to poet-activist John Greenleaf Whittier in 1847,

"'Where is Weld?' He is in a ditch opposite his house, doing the work any Irishman could do for 75 cents a day."

Near the heart of their discouragement was the insight that slavery is sin: not merely an unfortunate institutional arrangement, but an act of prideful rebellion against God. An American's natural predisposition, on seeing a sinful institution, is to try to outlaw it. The abolitionists saw, however, that this would not be enough. Sin corrupts the heart, and how could they affect slaveholder hearts by changing the law? Supposing they were able to make slavery illegal. Would that change the stain of racism and pride? So, in the beginning, abolitionists abjured politics.

Abolitionists set out to convince slaveholders to repent of their sin. They did so first by mailing publications to prominent citizens in the South. Soon they discovered that Southerners were not only unready to repent, but would not even tolerate the voice of the preacher. Abolitionist pamphlets were collected at Southern post offices and burned, their authors hung in effigy. Southern newspapers advertised large rewards for the lives of William Lloyd Garrison or Arthur Tappan. (Tappan, in perhaps his only recorded attempt at humor, was supposed to have said regarding the $100,000 offered for him, "If that sum is placed in a New York bank, I may possibly think of giving myself up.")

It was not just the South that refused to listen. Even in the North, abolitionist opinions were regarded as inflammatory and dangerous: 1834 saw three days of rioting in Manhattan in which churches with anti-slavery sympathies were trashed, homes were wrecked or burned, and the Tappan Brothers store, one of the most prominent in New York, came within an eyelash of being destroyed while the police stood by. In Boston a mob led Garrison through the streets with a rope around his neck. The police rescued him by putting him in jail. In Cincinnati, James Birney's printing press was dragged through the streets and thrown in the river; he hid for days to escape violence. In Alton, Illinois, editor Elijah Lovejoy defended his press from similar mobs and was shot and killed. In hundreds, perhaps thousands of towns, abolitionists who tried to give lectures were stoned, beaten, tarred and feathered, or at least physically threatened.

To say the least, abolitionists' naïve expectation that their simple religious logic would win a quick response proved badly mistaken. Naturally this was discouraging, most of all because it revealed so much about their fellow citizens. There was no "moral majority." The character of America was determinedly racist; appeals to moral conscience were not only not heeded, but violently resisted.

The Failure of Churches

A parallel attempt at persuasion occurred in denominations. Abolitionists thought they could use church machinery to catch slaveholding consciences. For example, if the Presbyterian General Assembly would recognize slavery as sin, then any slaveholding Presbyterian would be refused communion until he freed his slaves.

But here, too, obduracy was stronger than abolitionists expected. The major denominations were willing to split North and South—and did—rather than yield on the question of slavery. The only legacy of abolitionist argument seemed to be rancor, bitterness, and division.

Abolitionists were left disillusioned about the character of their fellow Christians and the churches they shared. Garrison and his Boston followers, along with other separatistic "come-outer" believers, completely left organized religion during this phase. The rank and file continued in church but were discouraged. They no longer believed that a simple appeal to right would win the hearts of their fellow Americans—or even of the broad range of their fellow Christians.

If straightforward moral appeals will not work, what next? The bitter 1840 split that all but destroyed the American Anti-Slavery Society was ostensibly about whether women could serve as society officers. The question of politics lay underneath, however. Garrison had grown more convinced that politics, whether in church or society, could never do good. The system was evil, so that even to vote, he famously declared, was "sin for me." He dramatized this conviction one Fourth of July by publicly burning the Constitution. Rather than engage in politics, he chose to provide a noisy moral conscience to a sinful nation.

Most abolitionists were not so pure. Many were loyal Whigs or Democrats, still seeing their parties hopefully. They had always voted, and continued to vote, trying to find candidates who would support their positions. It became common to question candidates regarding their positions on slavery, and to publish the results as a kind of forerunner of voter's guides.

Many abolitionists hung between politics and prophetic morality. And many grew disillusioned by the rank politics and evident racism of the major parties. Thus the Liberty Party was born, running former slaveholder James Birney for President in 1840 and 1844. The Liberty Party confined its concerns to slavery. Electorally its fate was that of all single-issue parties in American history: Birney received a negligible number of votes. His only impact was to split the Whig vote in New York and elect slaveholder James Polk to the presidency, ensuring the annexation of Texas as a slave state. This was hardly a reason for most abolitionists to rejoice in politics.

Yet they did not give up on politics. The Liberty Party—most of it, anyway—merged with disgruntled Democrats and Whigs to form the Free Soil Party in 1848. This represented a classic case of political coalition-building. Abolitionists—many of whom considered themselves more politically shrewd than they really were—joined a party that contained some frankly racist members, on the belief that they could manipulate it toward their own ends. They even accepted Martin Van Buren as their presidential candidate, though he was the very man who, as President, had tried to send the Amistad slaves back into captivity.

What Looks Like Failure

The abolitionists' experiment in politics failed on two counts. They found that their real influence in the party was negligible—politicians promised them vague blessings in exchange for their support but gave them nothing concrete. More importantly, the Free Soil Party with its watered-down commitments still won practically nothing on the national scene. They had compromised for the promise of politics, but gained the wind.

No wonder, then, that the rise of the Republican Party from the ashes of Free Soil won little interest from abolitionists, or that the nomination of Abraham Lincoln by that party in 1860 was treated with scorn by most abolitionists. Lincoln was a frank moral compromiser. He was willing to preserve slavery, only opposing its extension into the rest of the nation. His party included many candid racists. Though many rank-and-file abolitionists voted for him, no doubt, they did so without enthusiasm. Few recognized the man they would come to regard with such reverence.

Altogether the abolitionists appeared to be failures. Whether they pursued the pure morality of moral appeal, the modified purity of single-issue politics, or the compromising politics of coalitions and deals, they accomplished nothing visible except increasing rancor. They were blamed for the violence in Kansas, for the bloodshed over fugitive slaves, for the bitter feelings of the South, for the extremism that led to John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry—and with some justice. To preach against sin without success is to harden consciences and to create almost intolerable frustration.

Longtime abolitionist Gerrit Smith expressed this despair in 1855 when he concluded that "the movement to abolish American slavery is a failure." He saw this as a tragedy not only for slaves but for all America. "American slavery has left scarcely one sound spot in American character; and it is, confessedly, the ruler of America." He had lost all hope for moral change. "It is but too probable," he predicted, "that American slavery will have expired in blood before the men shall have arisen who are capable of bringing it to a voluntary termination."

He was right, of course: slavery ended through the worst bloodshed America has ever known. It represented a complete failure for America. Unable to find a political or moral solution to its most vexing issue, the nation divided and fought to kill.

And yet it would be wrong to agree with Smith that "the movement to abolish American slavery is a failure." For American slavery was abolished, and the abolitionists, who created the moral consciousness that led to a war, were very much responsible.

Before they began their work, there was only the mildest, sleepiest reaction against slavery in America. When they were done, millions of Americans stood against slavery. Change did not come as the abolitionists had hoped. It did not come as anyone had hoped. But it did come, and few would claim today that it was not change for the good, however bitter the circumstances.

The Plans of the Almighty

Of all the theologians who commented on this contemporaneously, Abraham Lincoln thought deepest and spoke most wisely. His Second Inaugural Address can be read as a commentary on the limits of politics, and on the deeper purposes that work beneath the surface strivings of politicians and activists and even those who pray.

The address begins with an utterly confounding pronouncement: No predictions about the future will be made, Lincoln says—a remarkable statement for a politician in power, whose armies at last seem to have swung the war in their direction. Indeed, Lincoln suggests, human plans have been confounded by the course of the war. Both sides, he notes, dreaded war and sought to avert it. Lincoln puts the result of their attempts in the cadence of a muffled drumbeat: "And the war came." The war came, unimpeded by the plans of both sides.

Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. … Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God. … The prayers of both could not be answered—that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has his own purposes.

Having established the futility of human planning, Lincoln probes the Almighty's "own purposes":

if we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God … he now wills to remove, and that he gives to both North and South this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to him? Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, "The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

Lincoln is reminding America that human effort is puny; and that God has his own purposes which rule the universe in ways we would not choose. Only having placed our actions in that grand context of divine justice does Lincoln conclude, in a single long, winding sentence, that we should "strive to finish the work we are in … with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right."

Lincoln's consciousness, I would say, ought to help us deal with discouragement. He would remind us that we must "strive to finish the work we are in," but we cannot afford to place too much trust in that work. We should work "with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right." We should agitate, and argue, and pray for a result we believe in—even as we know others hold opposite convictions with equal fervency. Yet God may work something more fundamental and astounding than anything we could guess.

The abolitionists, we see with hindsight, played a potent role in arousing the moral consciousness of the North regarding slavery. They failed at all their goals, and they failed even to arouse a majority to their point of view. They did, however, plant deeply the seed of revulsion for slavery and love for brothers and sisters of another color. They never expected that this seed would grow in a young mother, daughter of a famous clergyman, who would write it in a novel called Uncle Tom's Cabin. The abolitionists did not generally read novels, which they considered to border on the immoral. Still, Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel, sentimental as it was, stirred up the North to make white people feel that black people had human feelings. Few if any books have had the same effect on a nation.

The abolitionists' experience should teach us not to be discouraged, but not for any obvious reason. We cannot know whether we will ultimately succeed, and our trust ought not to rest in our plans and hopes. Rather we trust and hope in Almighty God, who rules our plans and makes of them results more fundamental and astounding than anything we can dream. His judgments, and his only, are "true and righteous altogether." Toward this trust, and this only, our discouragement should lead us.

Tim Stafford is Senior Writer for Christianity Today.

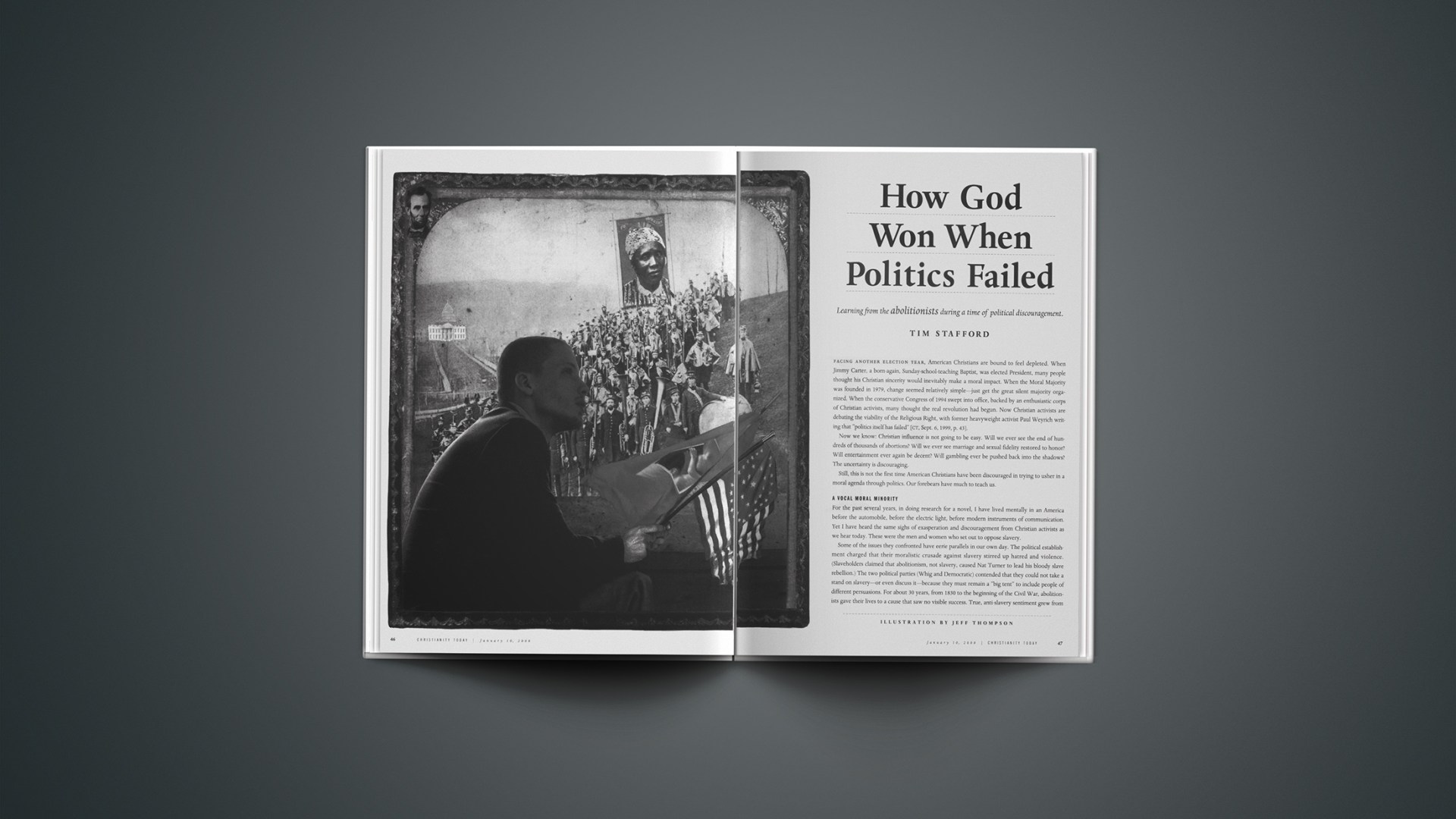

Photo credit: Fort Wayne Museum, Indiana

Related Elsewhere

Also appearing today at ChristianityToday.com is the first chapter of Stafford's Stamp of Glory: A Novel of the Abolitionist Movement (Thomas Nelson, January 2000). Stafford also had two articles about abolitionism in the September/October 1999 issue of our sister publication Books & Culture: "Abolition's Hidden History | How black argument led to white commitment," and "The Puzzle of John Brown" Another Christianity Today sister publication, Christian History, has repeatedly looked at slavery and abolitionism. Articles have included:

By Any Means Necessary | Black abolitionists were tired of waiting for a gradual, peaceful end to slavery (from issue 62:The Spiritual Journey of Africans in America: 1619-1865)

The Evil that Baffled Reformers | African slavery thwarted every effort to eradicate it (from issue 56: David Livingstone)

The 'Shrimp' who Stopped Slavery | The most malignant evil of the British Empire ceased largely because of the faith and persistence of William Wilberforce (from issue 53: Wilberforce and the Century of Reform)

A Profitable Little Business | The tragic economics of the slave trade (from issue 53: Wilberforce and the Century of Reform)

Christian History Issue 33, The Untold Story of Christianity and the Civil War, also included several articles on slavery and abolitionism. It is not available online, but can be inexpensively purchased online.

for more on abolitionism, see Britannica.com, the Library of Congress, and PBS's Africans in America. Earlier Tim Stafford articles for ChristianityToday.com and Christianity Today include:

CT Classic: Bethlehem on a Budget | Planning a church budget and the Christmas story share surprising similarities (Dec. 23, 1999)

The Business of the Kingdom | Management guru Peter Drucker thinks the future of America is in the hands of churches (Nov. 8, 1999)

Anatomy of a Giver | American Christians are the nation's most generous givers, but we aren't exactly sacrificing. (May 19, 1997)

God's Green Acres | How DeWitt is helping Dunn, Wisconsin, reflect the glory of God's good creation. (June 15, 1998)

God Is in the Blueprints | Our deepest beliefs are reflected in the ways we construct our houses of worship. (Sept. 7, 1998)

The New Theologians | These top scholars are believers who want to speak to the church (Feb. 8, 1999)

The Criminologist Who Discovered Churches | Political scientist John DiIulio followed the data to see what would save America's urban youth. (June 14, 1999)

Stafford also writes the "Love, Sex, and Real Life" column for Campus Life magazine, another Christianity Today, Inc. publication.

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.