One hundred years ago today, on December 22, 1899, Dwight Lyman Moody died in Northfield, Massachusetts, the same small town in which he had been born. Years before, Moody had anticipated this moment: “Someday you will read in the papers that D. L. Moody of East Northfield is dead. Don’t you believe a word of it! At that moment I shall be more alive than I am now. … I was born of the flesh in 1837. I was born of the Spirit in 1856. That which is born of the flesh may die. That which is born of the Spirit will live forever.”

More specifically, Moody embodied three principles that are highly relevant for what we face today. First, he modeled an evangelical unity focused on the gospel. Some have predicted the inevitable fragmentation and dissipation of evangelicalism in the post-Graham era, a replay of the fratricidal fights following Moody’s death. But history need not repeat itself. Evangelical unity is not a matter of patching together new coalitions, nor of devising a new superstructure. Jesus Christ is our unity, and his gospel is our message. Second, Moody showed love and generosity toward all, including those with whom he differed. This same note was sounded by the late Francis Schaeffer, who reminded us that love is the irreducible mark of the Christian: “We must not forget that the final end is not what we are against, but what we are for.”

Finally, both Moody and Graham nurtured a worldwide fellowship of faithful believers. Moody and Graham were Great Commission Christians and they proclaimed the many-colored grace of God unto the ends of the earth.

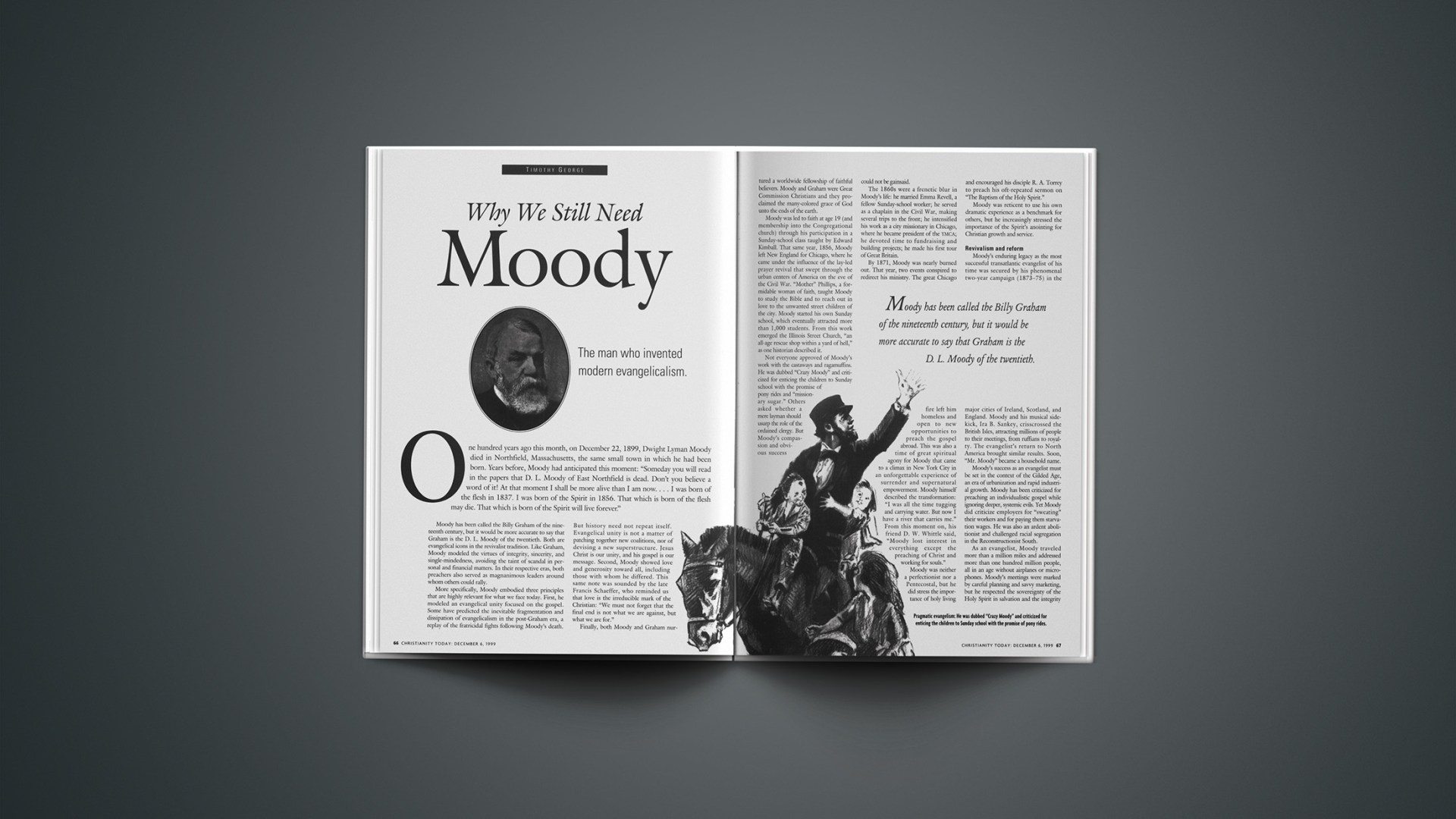

Moody was led to faith at age 19 (and membership into the Congregational church) through his participation in a Sunday-school class taught by Edward Kimball. That same year, 1856, Moody left New England for Chicago, where he came under the influence of the lay-led prayer revival that swept through the urban centers of America on the eve of the Civil War. “Mother” Phillips, a formidable woman of faith, taught Moody to study the Bible and to reach out in love to the unwanted street children of the city. Moody started his own Sunday school, which eventually attracted more than 1,000 students. From this work emerged the Illinois Street Church, “an all-age rescue shop within a yard of hell,” as one historian described it.

Not everyone approved of Moody’s work with the castaways and ragamuffins. He was dubbed “Crazy Moody” and criticized for enticing the children to Sunday school with the promise of pony rides and “missionary sugar.” Others asked whether a mere layman should usurp the role of the ordained clergy. But Moody’s compassion and obvious success could not be gainsaid.

The 1860s were a frenetic blur in Moody’s life: he married Emma Revell, a fellow Sunday-school worker; he served as a chaplain in the Civil War, making several trips to the front; he intensified his work as a city missionary in Chicago, where he became president of the YMCA; he devoted time to fundraising and building projects; he made his first tour of Great Britain.

By 1871, Moody was nearly burned out. That year, two events conspired to redirect his ministry. The great Chicago fire left him homeless and open to new opportunities to preach the gospel abroad. This was also a time of great spiritual agony for Moody that came to a climax in New York City in an unforgettable experience of surrender and supernatural empowerment. Moody himself described the transformation: “I was all the time tugging and carrying water. But now I have a river that carries me.” From this moment on, his friend D. W. Whittle said, “Moody lost interest in everything except the preaching of Christ and working for souls.”

Moody was neither a perfectionist nor a Pentecostal, but he did stress the importance of holy living and encouraged his disciple R. A. Torrey to preach his oft-repeated sermon on “The Baptism of the Holy Spirit.”

Moody was reticent to use his own dramatic experience as a benchmark for others, but he increasingly stressed the importance of the Spirit’s anointing for Christian growth and service.

Revivalism and reform

Moody’s enduring legacy as the most successful transatlantic evangelist of his time was secured by his phenomenal two-year campaign (1873-75) in the major cities of Ireland, Scotland, and England. Moody and his musical sidekick, Ira B. Sankey, crisscrossed the British Isles, attracting millions of people to their meetings, from ruffians to royalty. The evangelist’s return to North America brought similar results. Soon, “Mr. Moody” became a household name.

Moody’s success as an evangelist must be set in the context of the Gilded Age, an era of urbanization and rapid industrial growth. Moody has been criticized for preaching an individualistic gospel while ignoring deeper, systemic evils. Yet Moody did criticize employers for “sweating” their workers and for paying them starvation wages. He was also an ardent abolitionist and challenged racial segregation in the Reconstructionist South.

As an evangelist, Moody traveled more than a million miles and addressed more than one hundred million people, all in an age without airplanes or microphones. Moody’s meetings were marked by careful planning and savvy marketing, but he respected the sovereignty of the Holy Spirit in salvation and the integrity of each individual’s spiritual struggle.

A living theology

Moody was a vigorous, muscular Christian who, according to one English observer, had a “terrier-like aspect.” The rapid pace and excitement of his messages led to a concluding crescendo that “was like a cavalry charge. You had either to go with it or get out of the way.” Yet Moody held this kind of bravura in perfect equipoise with the most heartfelt tenderness. Sankey’s sentimental songs were matched note for note by Moody’s stories and anecdotes. One can hear echoes of the kind of narrative power that arrested so many in this sample of the evangelist’s preaching:

I can imagine when Christ said to the little band around Him, “Go ye into all the world and preach the gospel,” Peter said, “Lord, do you really mean that we are to go back to Jerusalem and preach the gospel to those men that murdered you?” “Yes,” said Christ, “go, hunt up that man that spat in my face, tell him he may have a seat in my kingdom yet. Yes, Peter, go find that man that made that cruel crown of thorns and placed it on my brow, and tell him I will have a crown ready for him when he comes into my kingdom, and there will be no thorns in it. Hunt up that man that took a reed and brought it down over the cruel thorns, driving them into my brow, and tell him I will put a sceptre in his hand, and he shall rule over the nations of the earth, if he will accept salvation. Search for the man that drove the spear into my side, and tell him there is a nearer way to my heart than that. Tell him I forgive him freely, and that he can be saved if he will accept salvation as a gift.

In his masterful survey of Moody’s theology, Love Them In, Stanley Gundry shows that—contrary to popular opinion—Moody’s preaching was theologically driven, structured around what the evangelist called the “Three Rs” of the Bible: ruined by the Fall, redeemed by the Blood, and regenerated by the Spirit. If Moody preached more about the love of God than the torments of hell, he did not deny the latter. Moody believed in the inerrancy and verbal inspiration of the Bible—”We ought to open the Holy Book as we would go into a sanctuary where we were sure of meeting our heavenly Father face to face, of hearing His voice”—though he counted among his close friends liberal evangelicals with less strict views of inspiration.

No doubt, Moody’s lack of formal theological training left him vulnerable to the attacks of unbelieving critics. Revivalism in general, and Moody in particular, have been accused of contributing to the evacuation of the evangelical mind, and there is some truth to this. Evangelistic good will and warm-hearted piety alone were not enough to stave off the inroads of liberalism and unbelieving theology in the decades after Moody’s death.

Moody was deeply grieved by the divisions he witnessed within the Christian family, and he longed for the day, he said, when all bickering, division, and party feeling would cease, when Roman Catholics and Protestants would see eye to eye and march together in a solid column against the forces of the Evil One.

Moody’s openness to Catholics was remarkable for the times. In Northfield, he contributed funds for building a local Catholic church, and he welcomed Catholic leaders to the platform of his 1893 Chicago campaign. Despite these initiatives of good will, Moody did not advocate an uncritical ecumenism. While preaching in Dublin, Ireland, he challenged the Catholic doctrine of purgatory and spoke against priestly confessions.

He also broke with his sometime associate, the temperance leader Frances Willard, because of her association with Unitarians who denied the divinity of Christ. Moody’s overriding concern was that the gospel of Jesus Christ be proclaimed to all people everywhere. For this reason, he opposed what he called “this miserable sectarian spirit” among orthodox believers.

If Mr. Moody were able to observe our fragile evangelical fellowship today, he would probably have a similar message for us. He’d be encouraged by our growth and increased opportunities for ministry. But he’d likely remind us that, in the midst of our big numbers, fancy buildings, and newfound political clout, we must not neglect the heart of our mission—extending the love of Christ to a lost world and to one another.

Timothy George is dean of Beeson Divinity School of Samford University and senior adviser forChristianity Today.

Copyright © 1999 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.