Jesus and the GDP I wish I could say that these stories are now personal ancient history and a source of a good retrospective laugh. I wish I could report that, like in the movies, all of our dreams quickly came true, just the way we imagined. In truth, it takes all our mental and spiritual strength to hold on to our vision in the face of one disappointment, delay, and discouragement after another. Even though we have had plenty of manna in this wilderness time, I wrestle with God over what feels like abandonment.

I wrestle with an image of how I thought my life would go. I hate what seems to be wandering in circles and wonder where I misplaced that upwardly-mobile road map that was tucked into my college diploma. Just thinking that way makes me even more ashamed of my pettiness and lack of trust in God for more than just a good parking space at the mall.

I am ashamed that my allegiance to Christ often slips into merely wanting him to sanction my worldly desires.

Yet I am beginning to see that my dissipation is in direct proportion to how much I have allowed the world of advertising and consumption to influence me. It does not only seek to eradicate my sense of identity, but more alarmingly, invades my spiritual life with its hyper self-consciousness and exaltation of languor. As our participation in that world has waned of late, I have noticed that my husband’s soul is being freed and forged into something new. Mine, on the other hand, is in meltdown.

After 25 years of trying to follow Christ, I am ashamed that my allegiance often slips into merely wanting him to sanction my worldly desires. Lately, as I have not been able to satisfy every last whim, I am frantic inside. To deal with the gap between my fears of going down the drain and my fears of being honest, I put on my carefully crafted Christian mask.

When I play the role of a Christian, she is a very glib character indeed. In fact, I have grown quite bored of self-affirming babble, trying to explain what God is doing in my life. I am tired of the absurdity of my entire faith centering on my personal emotional health. I know Jesus doesn’t stand at the gate of earthly happiness, promising me my portion of the gross domestic product (GDP). Christ bids me come and die to my rights to it.

Still, I allow myself, my inner self, to be compared to others—not others’ inner selves, but to what material things they may possess. Because we live in a typical suburban neighborhood that borders some other rather affluent ones, those messages assume tangible forms.

I see shopping bags from nice stores lying around friends’ houses and hear regularly about impressive family vacations. Once, standing in the grocery line behind a well-heeled woman easily ten years my junior, I caught a glimpse (it was entirely accidental) of her very ample checkbook balance. (I could have gotten a year’s worth of groceries with that much, but it was an accident—really.) After watching her wheel of Brie and jar of macadamias float easily down the conveyer belt, my peanut butter and pork and beans looked like I felt.

A low-grade guilt overtakes me when my defenses are down. How do I expect my kids to become fully functional adults if they wear hand-me-down and thrift-shop clothes? When I wear my second-go-round Liz Claiborne skirt or Gap vest, I fear some well-dressed acquaintance, who is about my size, will expose me. She, in my imagination, says, “I like your skirt, Lee. I used to have one exactly like it but I gave it to the Goodwill.” And in my best lockjaw I respond, “Really dahling, what a strange coincidence.” If I am not careful I will pass on my shallowness to the boys. Once in a while I wonder how they will make it in this world if they only play golf on public courses. How can they be informed without cable television? Am I dooming them to a look-but-don’t-touch life?

To make matters seem worse, during the time our family budget imploded, the U.S. economy exploded. (A few years back we sold the only stock we ever owned for a $2 per-share loss. Six months later it had tripled in value.) The steady stream of good news from Wall Street makes it seem as though the world is having an elegant, titillative party, and I am not invited. Even some of my Christian friends are inside, having a big time. But when I show up outside the gate, trying to slip in unnoticed, the door is slammed in my face. I am left on the outside, feeling anxious and, even worse, invisible.

And where is Jesus in all of this? Why couldn’t he usher me into this grand party? In my dense superficiality, I wonder why Jesus wouldn’t give me just a little cause to celebrate. Even though I know all good gifts are from heaven, deep down I long for the ones made in Germany.

Our health and wealth gospel Whenever I fall into this pity party, I make my way to a place that has the best deals in town. In fact, everything inside is free. I go to the library.

In a book of essays I found titled The Culture of Consumption, historian Jackson Lears examines the psychological effects that consumption has had on Americans. Whereas earlier Americans (when we were citizens, not consumers) were inner-directed, having their identity revolve around a higher principle, modern Americans can be termed other-directed.

Lears notes that the other-directed person is just “an empty vessel to be filled and refilled according to the expectations of others and the needs of the moments.” People’s identities consist of the masks they put on, masks that either make them look successful or help them get success, allowing those around them to define who they are.

Lears quotes the Atlantic Monthly on the changing nature of individuals. “We are a mass. As a whole we have lost the capacity for separate selfhood.” To my surprise, I noted that the Atlantic quote is from 1909.

Although the essay centered on the turn of the century, its explanations shed light on my present confusion. I have lost my separate selfhood, or at least momentarily misplaced it. Instead of finding it in my rich family heritage, or in the gifts that have surfaced in me, or in the laughter of my children, I have gotten sidetracked by the consumer culture’s claims that I am incomplete and needy.

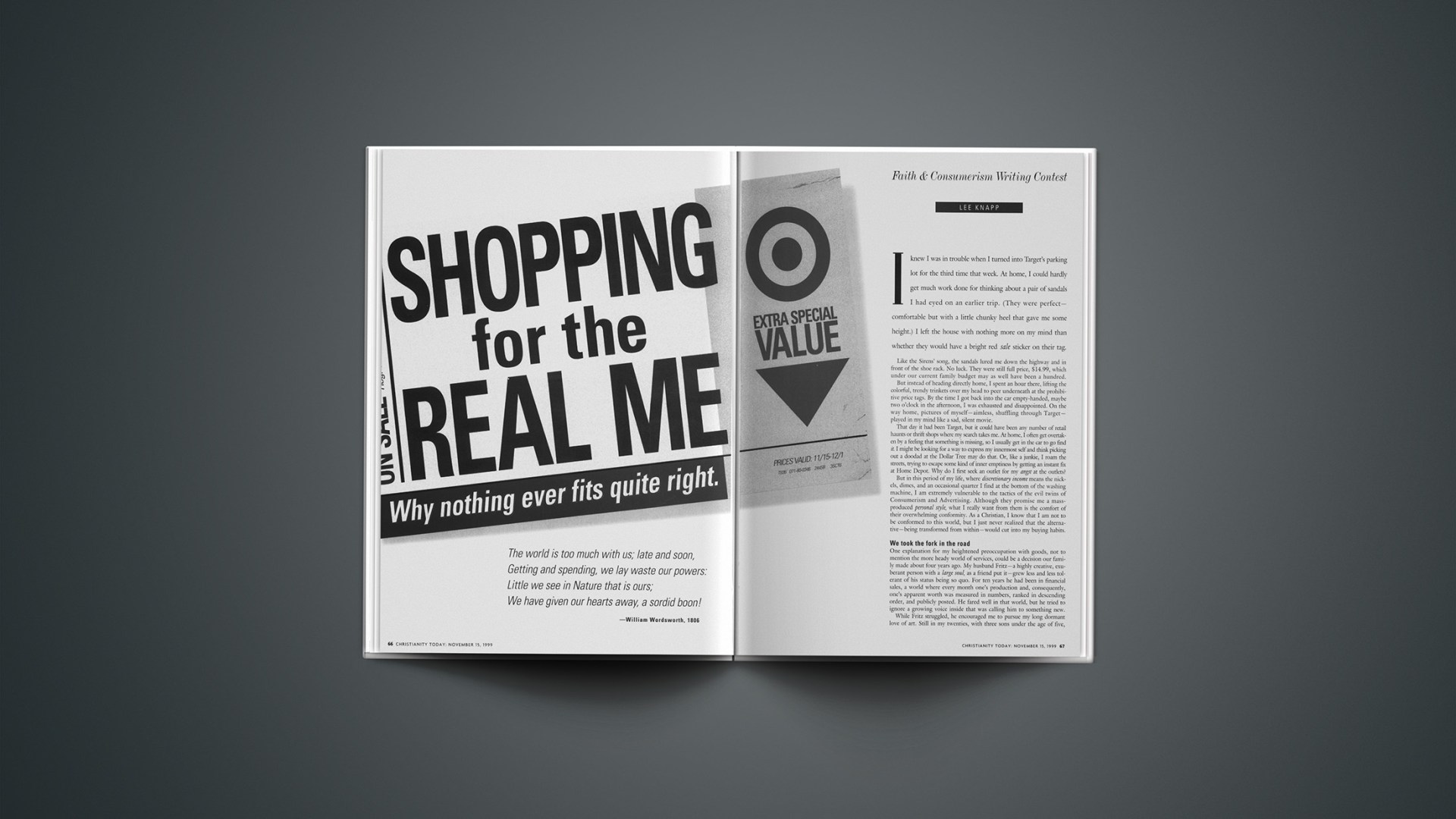

In this time when it seems that I am floating aimlessly, I look to things to give me a “lifestyle” in place of this struggle known as life. But trying to manufacture an identity is exactly like going shopping and leaving the dressing room empty-handed. Nothing ever seems to fit quite right.

Like a junkie, I try to escape inner emptiness by getting an instant fix at Home Depot.

Realizing that a wholly other way of life, as well as notions of self and God, motivated people in the decades leading up to this present century gives me more perspective and hope. “Inner-directed” people once lived a more restrained and modest life, a life that made sense, one that was integrated and not so grotesquely self-conscious. During some of that time, people went to church to feel bad, not good. But then they were moved to repent, and in that cathartic experience were restored to God. Humility, which has the same root as humus or dirt, kept men and women grounded. From almost the beginning of Protestantism, it was thrift, not material “blessing,” that marked the Christian. If someone did have wealth, flaunting it brought ostracism, since in some groups excessive spending was seen as stealing from God. There was a time when humanity’s view of God’s view of humans had nothing to do with finances.

Yet in the early twentieth century, Lears notes that Christianity became limp and flabby, its prominent preachers adapting the gospel to a nation that was yearning to restore the health it once enjoyed when life was more real and experience, not to mention personality, was less fabricated. As an example of the contrast, he cites one of the leading ad men of the day, Bruce Barton, who struggled to integrate his Protestant upbringing with his business philosophy. He claimed that “it was no accident that credit, the basis of modern business, was derived from credo, I believe.”

Barton fancied advertisers and businessmen as ministers of Christ for the good they could do. He brought his two worlds together, advertising and Christianity, by promoting consumption as a healing balm to an increasingly secular America.

Finally, Lears writes that the abundant life got confused with a perpetual good mood. Since old concerns of the next day’s meals eased in the advent of excess goods, emotional needs took over. In this climate, the kingdom of God is good self-esteem. In the 1910s the anxiety about change and maintaining a respectable status was termed “overpressure.” Today it is called stress. Perhaps Jesus is entreated less to forgive sin than to relieve stress. Christianity becomes one more self-help program.

I can sometimes see, superimposed on my heart, a ladder, a spiral staircase that leads me upward to God. My spiritual life, in the light of an image-conscious society, can be one more thing to improve about myself with the application of some miracle formula. Do I look to Christian books and magazines and listen to tapes and sermons merely to improve the quality of my inner life, to find relief from the madness of the twentieth century? This is not a healthy motivation. To grow in Christ is a good goal, but growth occurs in seasons, and involves a cycle of death as well as a time of blooming. Most of it is done in complete darkness, known only to God.

Continued on next page | The camel, the needle, and me

Copyright © 1999 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.