The Family Life Center lies on the edge of Baton Rouge just down the road from the newly opened Mall of Louisiana. The parking lot for the shopping mall is burgeoning on a Sunday, while the acres of parking for the Family Life Center are nearly vacant. Such a contrast might occasion yet another commentary on spiritual apathy, misplaced priorities, and the false gods of consumerism, until one remembers that the preacher behind the pulpit at the Family Life Center on this Sunday—as well as most Sundays—is a man named Jimmy Swaggart.

To suggest that Swaggart is behind the pulpit, however, is somewhat misleading; he has never submitted easily to the constraints of pulpits—or, for that matter, to any other conventional boundaries. Instead, he bobs and weaves and shouts and cries and spins his own magic. “Preaching is like an orchestra,” Swaggart told me. “You have to be loud one moment and quiet the next. You’ve got to keep the people’s attention. You’ve got to keep the people’s attention.” Throughout a raucous and controversial career now in its fourth decade, Jimmy Swaggart has rarely had trouble keeping people’s attention.

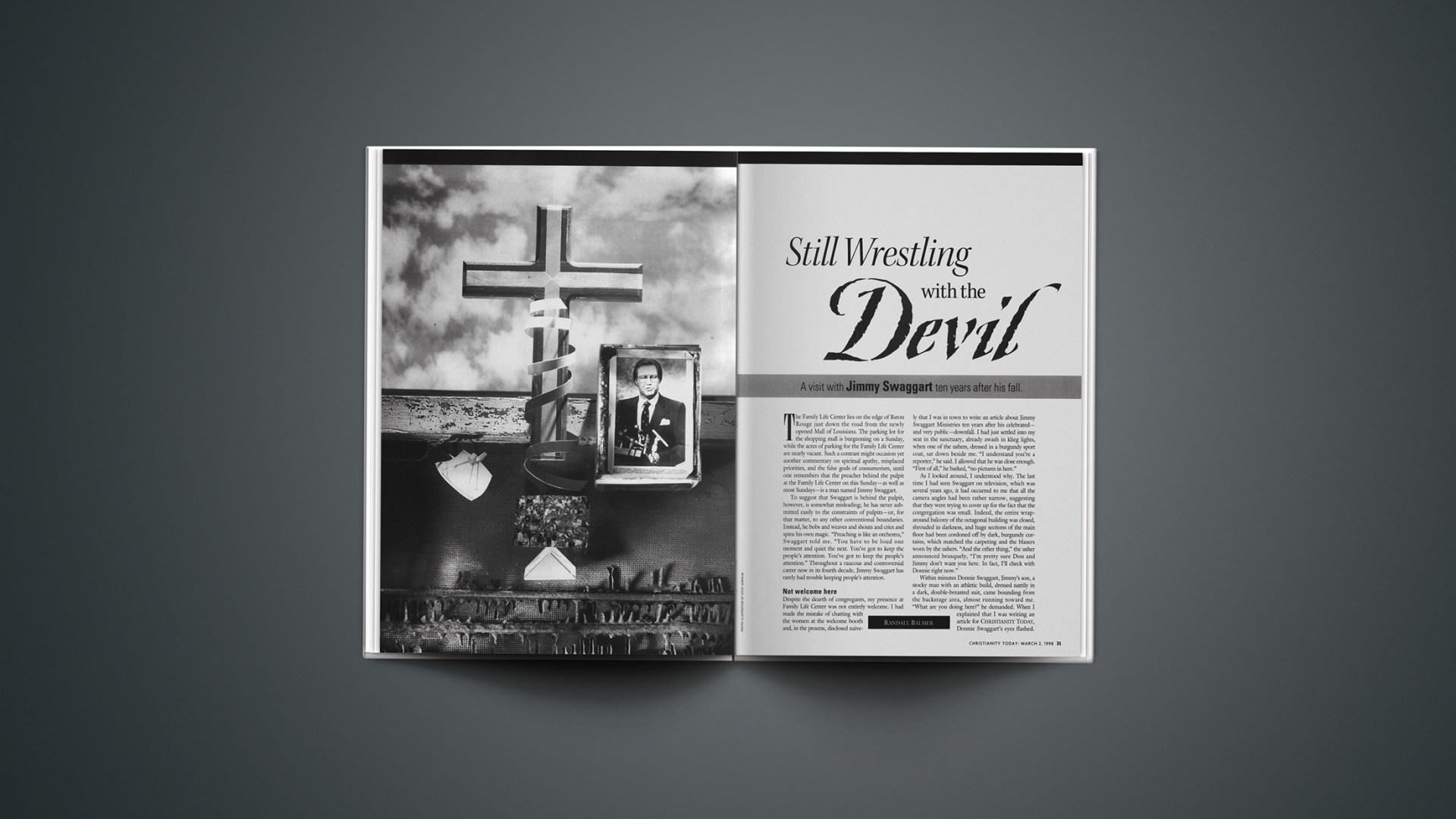

NOT WELCOME HERE Despite the dearth of congregants, my presence at Family Life Center was not entirely welcome. I had made the mistake of chatting with the women at the welcome booth and, in the process, disclosed navely that I was in town to write an article about Jimmy Swaggart Ministries ten years after his celebrated—and very public—downfall. I had just settled into my seat in the sanctuary, already awash in klieg lights, when one of the ushers, dressed in a burgundy sport coat, sat down beside me. “I understand you’re a reporter,” he said. I allowed that he was close enough. “First of all,” he barked, “no pictures in here.”

As I looked around, I understood why. The last time I had seen Swaggart on television, which was several years ago, it had occurred to me that all the camera angles had been rather narrow, suggesting that they were trying to cover up for the fact that the congregation was small. Indeed, the entire wraparound balcony of the octagonal building was closed, shrouded in darkness, and huge sections of the main floor had been cordoned off by dark, burgundy curtains, which matched the carpeting and the blazers worn by the ushers. “And the other thing,” the usher announced brusquely, “I’m pretty sure Don and Jimmy don’t want you here. In fact, I’ll check with Donnie right now.”

Within minutes Donnie Swaggart, Jimmy’s son, a stocky man with an athletic build, dressed nattily in a dark, double-breasted suit, came bounding from the backstage area, almost running toward me. “What are you doing here?” he demanded. When I explained that I was writing an article for CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Donnie Swaggart’s eyes flashed. “I don’t like the press,” he bellowed. “How come you didn’t tell us you were coming?” I explained that I had called the office several times over the preceding weeks to inquire about dates and that I had made no attempt to hide my purpose for visiting. “Well you didn’t talk to me,” he said, his tone softening slightly.

“Listen, I’ve seen characters like you before,” he continued, resuming the bluster and wagging his finger in my direction, “and you know what? It’s the so-called Christians who are the worst.” Ten o’clock was fast approaching, and Donnie had to assume his place on the stage. “Just remember,” he continued, “blood is thicker than water. Do whatever you want to me, just don’t touch my parents or my kids. If you do, I’m coming after you, you understand?”

Although I found these threats more amusing than intimidating—should I expect a knock on the door some night from a couple of thugs with cigarettes dangling from their mouths: “Hey, buster, some preacher fella from Baton Rouge wants to have a little chat with you”?—Donnie Swaggart clearly was paranoid about my presence. Throughout the service he kept stealing glances in my direction. A rather large usher whose name tag read “Bill Wilson” was assigned to follow me, tracking my serpentine movements after the service. Although I managed to lose him a couple of times, he caught up with me, breathing a bit heavily, and resumed his surveillance. When I approached Jimmy Swaggart, who had changed into a turtleneck and was greeting congregants near the stage, Wilson fidgeted nervously but kept his distance.

Swaggart himself couldn’t have been more gracious. He is a kind man who, unlike some other “televangelists,” is not afraid to meet your eyes. Lest there be any confusion or false pretenses, I informed him immediately of my purpose for visiting Baton Rouge and told him of my admiration for his preaching abilities. The mention of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, however, brought a change in his countenance, not so much anger or defiance, as it had with Donnie, but sadness. “I’m afraid I won’t be able to help you,” he said, shaking his head. “That magazine has said some pretty hurtful things about me.” He shifted his eyes briefly toward the middle distance, then back at me. From the corner of my eye I could see my tail, Bill Wilson, shuffling nervously.

“Listen,” Swaggart said kindly, “I’m not always right about this, of course, but I’m pretty good at judging people, and I detect a good spirit about you. But I don’t want anything to do with that magazine. In fact,” he continued, suddenly laughing, “I don’t even want anything good about me going into that magazine!” He grabbed my hand, shook it warmly, and drove home the point. “I’m sorry. If you were writing for the Washington Post,” he said, “that might be a different matter.”

As I turned away, back toward Bill Wilson, so we could resume meandering around the Family Worship Center, I too was sorry. Jimmy Swaggart is an enormously likable man, and I would have loved to chat for awhile about life and preaching and failure and grace and the many doctrines we held in common, including providence.

MENTORING JIMMY Little did I know that an affirmation of providence would occur within the hour, but to understand the scale of this theological demonstration I must reveal a mundane personal detail: I rarely eat lunch—once or twice a month, at most, and only when a business or social occasion demands it. As I pulled out of the parking lot at the Family Life Center, however, and drove past the vast array of restaurants on Bluebonnet Avenue, I abruptly decided to pull into a large, well-advertised seafood restaurant. I wanted to look through Swaggart’s autobiography, To Cross a River, which I had just purchased in the bookstore, and, relieved that Bill Wilson and the usher corps had not confiscated my notebook, I wanted to review my notes from the morning.

The hostess seated me at a table next to a fairly large group, headed by none other than a man wearing a gray turtleneck—Jimmy Swaggart. He noticed me almost immediately and, without a moment’s hesitation, invited me to join them. I assured him that I had not followed him to the restaurant, but he was unconcerned and introduced me all around—his wife, Frances, his mother-in-law, and a missionary family from South Africa.

Swaggart was relaxed and expansive. Although he dropped out of high school, he is an exceedingly bright, literate, and articulate man. In the course of our conversation he talked about the preachers who had influenced him, A. N. Trotter and John R. Rice, a fundamentalist with whom Swaggart had formed an improbable friendship. “I’ve preached a lot of his sermons over the years,” Swaggart said, citing one of his favorites in particular, whose theme was “all the Devil’s apples got worms.” He said that he had developed “my own style,” but he very much admired the oratorical abilities of Martin Luther King, Jr., E. V. Hill, and “some white guy with a bald head.” When I ventured the name Tony Campolo, Swaggart recognized it immediately. “Yeah, that’s him! That guy can preach,” he said, slapping the table with evident appreciation.

Swaggart’s autobiography cites a couple of other preachers as influential in his early years. J. M. Cason, a young evangelist, held revival meetings in Swaggart’s hometown of Ferriday, Louisiana. He made an impression on Swaggart as “a highly emotional man who cried and preached at the same time.”

Another young preacher, Cecil Janway, also played the piano. Swaggart remembers that he “brought life” from the church’s ragged upright piano, “life which flowed throughout the church building.”

To this day, Swaggart opens his services at the keyboard, his right leg thumping up and down in time to the beat. As with many Pentecostal services, the opening songs blend seamlessly one to the next. “There is power in the blood” segues into “Alleluia, fill us afresh today.” As the music whips the congregation into a frenzy, Donnie Swaggart claps and hops in time to the beat and then grabs a microphone. “I’m here to serve notice on the Devil today,” he exclaims, “there’s power in the blood. There’s power in the blood of Jesus Christ.” The congregation concurs with shouts and applause. “There’s a new sheriff in town,” Donnie announces. “The Devil has been defeated!” He does a little dance as the music segues back into “Power in the Blood.”

If God forgot Swaggart’s transgression, few others did.

After still more music and an exhortation to “give the Lord a big hand,” the crowd hushed as a woman in the front row spoke in tongues. Someone from the choir offered an immediate interpretation. Donnie once again grabbed the microphone. “I don’t know if you can hear it. The Holy Ghost is saying, ‘I’m about to enlarge your borders here at the Family Worship Center. There’s not going to be an empty seat in the house.’ “

TRUE CONFESSION—SORT OF For ten years now, there has been a surfeit of empty seats in the Family Worship Center, which has a capacity of 7,500. The last full house, in fact, gathered to witness the famous confession on February 21, 1988. “I do not plan in any way to whitewash my sin,” Swaggart said in the wake of disclosures about having visited a motel room with a prostitute. “I do not call it a mistake, a mendacity. I call it sin.” In a soliloquy that was baroque and eloquent at the same time, Swaggart apologized to his wife, his son, and his daughter-in-law.

He apologized to the Assemblies of God, “which helped to bring the gospel to my little beleaguered town, when my family was lost without Jesus, this movement and fellowship that girdles the globe, that has been more instrumental in bringing this gospel through the stygian night of darkness to the far-flung hundreds of millions than maybe any effort in the annals of history.” He apologized to the “godly” pastors of the Assemblies of God, to its evangelists and missionaries.

Finally, Swaggart apologized to Jesus, “the one who has saved me and washed me and cleansed me.” Swaggart’s jaw quivered; rivulets of tears flowed down his cheeks. His eyes turned toward heaven. “I have sinned against you, my Lord, and I would ask that your precious blood would wash and cleanse every stain until it is in the seas of God’s forgetfulness, never to be remembered against me.”

The performance was vintage Swaggart—complete with anguish and tears and self-flagellation—but if God forgot his transgression, few others did. For Swaggart’s many critics, moreover, he had finally received his comeuppance. Swaggart had earlier criticized “pretty-boy preachers,” a thinly veiled reference to Jim Bakker, his fellow Assemblies of God minister and rival televangelist. Marvin Gorman, a Pentecostal preacher from New Orleans, had also tangled with Swaggart, and Gorman was the one who produced evidence that Swaggart had entered a Louisiana motel room with a prostitute—not for a sexual liaison, it turns out, but to engage in some sort of voyeurism.

Believers shuddered at the toppling of yet another televangelist, and the media, already in a feeding frenzy in the wake of Bakker’s tryst with Jessica Hahn, had a field day. Swaggart became the object of ridicule and derision. He had engaged in something that was portrayed not so much as immoral as it was tawdry. Some commentators made much of the fact that Hahn (after the requisite plastic surgery) appeared in Playboy, while the woman linked with Swaggart appeared in Penthouse.

Swaggart promised to submit to the discipline of the Assemblies of God, with whom he held ordination credentials. He offered what the denomination characterized as a “detailed confession,” which demonstrated “true humility and repentance” on Swaggart’s part. While the Louisiana District of the Assemblies of God imposed a three-month silence, which Swaggart accepted, the denomination extended the discipline to two full years. Swaggart, however, chose to abide by the Louisiana punishment. He resumed preaching on May 22, 1988, Pentecost Sunday, explaining that “Jesus paid the price” for his sins. Swaggart may have had little choice. Put simply, the scale and the reach of his operations in Baton Rouge and around the world demanded a steady infusion of cash. Donnie was not yet ready to step in—he had neither the experience nor the charisma—and Jimmy recognized that he had to go back on the air in an effort to salvage the various components of his empire.

In retrospect, that decision was probably a miscalculation. “He has isolated himself from those who could have helped eventually restore his ministry with integrity,” CHRISTIANITY TODAY opined. “Swaggart was too impatient, too friendly with power, too short-sighted to see beyond his immediate desires and goals.”

The General Presbytery of the Assemblies of God defrocked Swaggart for violating the terms of their suspension; Swaggart had burned his bridges with his own denomination. His basic constituency had already eroded, and Swaggart certainly did not help himself with his own recidivism. In 1991 he was stopped by police in Indio, California, while driving with a woman who claimed to be a prostitute. The result was predictable. More scorn, more ridicule, more empty seats.

FIRE IN HIS VEINS The compound that straddles Bluebonnet Road has a forlorn look to it. With the huge infusions of cash from his television program—Jimmy Swaggart Ministries pulled in $141.6 million in 1986, the last full year before the scandal—Swaggart had built an impressive empire: the massive Family Worship Center, television production facilities, an administrative center for his worldwide operations, and Jimmy Swaggart Bible College across the street.

Most of the flagpoles, each of which once represented a foreign nation where Swaggart maintained a presence, are empty. The fountains are dry, the landscaping neglected and overgrown. At the Bible college, weeds and a chainlink fence surround the shell of what was to be a high-rise dormitory, its construction abruptly halted after the scandal. Only about 45 students attend the school now, Swaggart told me wistfully, a campus built to accommodate hundreds more. The entire scene resembles a fly trapped in amber, frozen in time.

And yet, a decade after the scandal, Swaggart soldiers on. He leaves the piano, steps onto center stage, removes his glasses, and exclaims, “I don’t know about you, but I’m happy this morning!” He initiates a reprise of “I’ve got the Holy Ghost down in my heart, just like the Bible says,” and then, referring to a recent downturn in the financial markets, remarks: “If you get your joy out of Wall Street, well, you got quite a jolt a couple of weeks ago.” He invites members of the congregation to come forward for healing. As the choir and the congregation sing “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty,” Swaggart, his son, and several elders pray for each one. Swaggart took particular compassion on a man who was badly deformed. “Lord, touch my brother,” he cried, with his hands on the man’s forehead, “from the top of his head to the soles of his feet.”

Divine healing has always been a central tenet of Swaggart’s ministry. The death of his baby brother, Donnie, when Jimmy was only four made a deep impression on him. While preaching his first revival in Sterlington, Louisiana, Swaggart came down with pneumonia (the same illness that had felled his brother). Swaggart went to the hospital but left after a couple of days, still burning with fever. He fell into a deep depression. “Dark, gloomy thoughts roamed through my mind,” Swaggart recalled. “It seemed as if every demon in hell had crawled out to do battle with me.”

He read a passage from the Book of Joshua, with the admonition to be strong and of good courage. “God’s healing power surged through my body,” Swaggart said. “It was like fire in my veins.” He went on to impart his healing gift to others—as well as to the battered, blue Plymouth he used during the early years of his itinerancy.

DOWN IN THE BAYOU The quickest route from Baton Rouge to Ferriday, Louisiana, is U.S. 61, also known as the Great River Road. It winds north past refineries along the Mississippi River, past antebellum plantations that have been turned into museums, and past sharecroppers’ cabins sitting next to their modern counterpart, that peculiarly American oxymoron, the mobile home. Baptist churches outnumber gas stations and restaurants and taverns and just about every other sort of establishment in the piney woods of Mississippi. At Natchez the road connects to U.S. 84 west across the kudzu banks of the Mississippi River and back into Louisiana to Ferriday.

When I told Swaggart that I planned to visit Ferriday, he said, “Well, it’s still there.” The large sign on the edge of town, just past Martin’s Auto Shop & Used Tires, reads: Ferriday, La, Visit Our Museum, Home of Jerry Lee Lewis, Howard K. Smith, Mickey Gilley, Peewee Whittaker, Jimmy Swaggart, Ann Boyar Warner.

Ferriday is a town of convenience stores, cinder-block Laundromats, and abandoned houses. Most of the shops along Louisiana Avenue were shuttered years ago, although the hardware store and the pawnshop remain open. Many of the houses in town, not just the mobile homes, sit atop piles of bricks or cinder blocks, testimony to the perils of life on a floodplain. Poverty abounds on both sides of the tracks, although even the tracks themselves were removed some years ago.

After driving around town for half an hour, I still hadn’t located the Assembly of God that had been organized in 1936 by Pentecostal missionaries Mother Sumrall and her daughter Leonia. When I asked for help in a convenience store, one of the customers interjected, “Oh, I can help you. Jimmy’s my cousin.” Carolyn Magoun, who later clarified that she was actually Frances’s cousin, not Jimmy’s, directed me to the First Assembly of God at the end of Texas Avenue. The Swaggart house, she said, had been torn down a long time ago.

When I offered that Jimmy Swaggart has had a rough time in recent years, Magoun agreed. “Yes, he has,” she said, shaking her head, “but people just forget that we’re all human.” She added that when Frances Swaggart grew tired of the media glare during her husband’s troubles, she would often slip away to Ferriday and Wisner, her hometown, just up the road.

The tiny clapboard building at the end of Texas Avenue was sagging somewhat, but it sported a fresh coat of white paint. I pulled into the gravel parking lot where Swaggart’s uncle, Elmo Lewis, Jerry Lee’s father, had pulled his sleek, black Cadillac in the spring of 1958, interrupting a church picnic. Elmo Lewis had just returned from Memphis with the news that Sam Phillips, the producer of Sun Records who had discovered Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis, had sent for Swaggart. Phillips had heard Swaggart sing and play the piano and found his keyboard style virtually indistinguishable from that of his cousin, Jerry Lee Lewis; he wanted to start a gospel line at Sun, with Swaggart as his first artist.

Swaggart was at that time, in his words, “a smalltime, wrong-side-of-the-tracks Pentecostal preacher” earning $30 a week—in good weeks. He had a wife and a young son and the battered, blue Plymouth. He preached in a $20 Stein suit and a single pair of shoes, while his cousin, known nationally as “the wild man of rock ‘n’ roll,” was pulling in $20,000 a week.

Uncle Elmo had left the Cadillac running. The contracts were waiting in Memphis, and Swaggart had been scheduled into the recording studio the next morning. Swaggart paused, surveyed the church folk, and said no. “I can’t do it,” he said finally, and the black Cadillac pulled away.

Swaggart believes that God gave him his musical abilities. After the arrival of Cecil Janway, the young preacher-pianist, to the Assemblies of God church in Ferriday, Swaggart prayed for a miracle. ” ‘Lord,’ I said, ‘I want you to give me the gift of playing the piano.’ ” Swaggart was so fervent that he even attached conditions to the request. ” ‘If you give me this talent, I will never use it in the world,’ ” he promised, adding, ” ‘If I ever go back on this promise, you can paralyze my fingers!’ ” The gift came that very evening, a gift that he tried to refine with lessons from the local band director, but Swaggart quit after four lessons, concluding that “playing by the book was a waste of time.”

PLAYING IT BY EAR Playing by the book has never been Swaggart’s forte. His preaching style is inimitable, and he is a consummate showman. (I often tell students that if they want to appreciate fully Swaggart’s artistry, tune him in on television, turn off the sound, and watch his facial expressions and his gesticulations.) At 11:30 on Sunday morning, an hour and a half after the service began, Swaggart announced, “I’m not going to preach long, just enough to get through.” He recited his text from memory: “I baptize you with water for repentance. But after me will come one who is more powerful than I, whose sandals I am not fit to carry. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire” (Matt. 3:11, NIV). He was already weeping. “I know I’m nothing.”

He recounted the baptism of John along the “reedy banks” of the River Jordan. Swaggart loosened his necktie. “I believe that Jordan rained with shouts that day,” he said. “There’s nothing like people getting saved.” His voiced cracked. “Forgive my emotion,” he said and then launched into a riff: “When people come to God, the drunkard puts down his bottle and the drug addict his drugs!” He recounted how “Jesus came to my house” when Swaggart was five; his parents were converted. “When they got saved,” Swaggart exclaimed, “the fighting ended.” Behind Swaggart, in the pastors’ gallery adjacent to the choir, Donnie Swaggart was sobbing convulsively. “I’m not going to push any more on this message this morning,” Swaggart said, after a pause. “Here’s what the Holy Ghost tells me to say to you right now,” he continued, pacing the stage. “Come to Jesus.”

And they came. Maybe not the hundreds, as in years past, but scores. They filed to the front steps, where boxes of tissues had been placed discreetly around the stage. Swaggart had invited them to come for salvation, for healing, for release from the bondage of sin or addiction.

Playing by the book has never been Swaggart’s forte.

As members of the congregation streamed toward the octagonal stage in response to Swaggart’s altar call, a fascinating tableau unfolded. Donnie Swaggart, having dabbed his tears, strode purposefully into the audience, picked out a good-looking young couple, guided them forward, and positioned them in front of one of the television cameras. He began praying fervently and animatedly. The camera’s red light flicked on obligingly, while the couple, especially the man, looked rather bewildered. Midway through the prayer, moreover, Donnie signaled to one of his associates to bring someone else. He moved to another camera and repeated the performance.

Donnie Swaggart clearly is positioning himself for an even greater role in Jimmy Swaggart Ministries. He is the heir apparent, and when his father announced on Sunday morning that Donnie would preach that evening, the son let out a whoop, prompting his father to compare him to a racehorse chomping at the bit.

When I arrived for the six o’clock service, my friend Bill Wilson was waiting for me in the lobby, still eyeing me suspiciously. Jimmy Swaggart again opened the service at the piano, while Donnie tried to imitate his father’s style. “The Devil does not own this town,” he shouted. “He doesn’t own this town. He doesn’t own this state. He doesn’t own this nation.”

In show business terms, Donnie Swaggart was dying out there, so his father stepped from behind the piano and, smooth as butter, came to the rescue. After a few remarks about his early days as a preacher he began spontaneously to sing “The Old Rugged Cross.” A woman near the stage was slain in the Spirit, caught as she fell backward by a man in a burgundy blazer. “Let me tell you,” Swaggart told the congregation, “you’ll make it if you hold to that cross.” The music shifted to “O, Happy Day” and then “Where Could I Go but to the Lord?” “The crippled man can still go to him,” Swaggart declared. “The drunk can still go to him. The lost sinner can still go to him.”

Donnie, wearing (honest to God) blue suede shoes—midnight blue loafers to match his shirt and his pocket square—again came to the microphone and this time rose to the occasion. His father, seated behind him, was his biggest cheerleader, offering hearty amens and applause. Donnie, preaching from Numbers 13, proved that he is a competent, even better-than-average preacher, “reading” his audience in good Pentecostal fashion, trying one theme after another until something clicks. That Sunday night, it was his recounting of an interracial revival he had preached recently in Orlando, Florida. “We don’t need Farrakhan,” he shouted. “We don’t need Jesse. We need Jesus!” The congregation cheered. “Racism is destroying this nation,” he continued, “but Jesus is the cure.”

The soaring rhetoric was a digression, but it worked; he had the attention of the audience. Swaggart then settled back into his theme, that “we are well able” to possess the land. For the younger Swaggart, that meant that the congregation, despite its setbacks in recent years, should move forward in faith. “The Devil took his best shot, but we are well able to go up and possess the land,” he said. “At times it doesn’t seem like there’s many of us, but there’s more for us than there are against us.” He talked about filling the cavernous Family Worship Center once again, and he even talked about resuming construction on the high-rise dormitory across the street. “Doubt says the church is half-empty, but faith says the church is half-full.”

THE FAITHFUL REMNANT In the course of the service, I had noticed a 30-something woman from afar. She had been one of the most enthusiastic participants in the service, arms outstretched, weaving back and forth with her eyes closed. Her name, I learned, was Vickie Whittenburg, and when I asked her why she attended Swaggart’s church, she replied that it was “the Word, nothing but the Word.” She professed not to be bothered by Swaggart’s past transgressions. “It’s the anointing, regardless of the sin in one’s life,” she explained. “It’s a gift from God, and God doesn’t take it back.”

Ralph Walker, an usher, stopped by to join the conversation. “Nobody can preach like Jimmy Swaggart,” he said. “I’ve never known anyone like him. I started listening to him on the radio. I was a heathen. I was just a rank heathen.” Walker began attending the church when “it was bulging at the seams,” he said, pointing to the empty balcony. “I had to stand at the back of the balcony.”

Both Whittenburg and Walker consider themselves a remnant of the faithful. Whittenburg was drawn to Swaggart, in part, because of her passion for the underdog. “He’s a fighter,” she said. “I’ve never felt that I wanted anyone to make it as much as him, regardless of any error or failing on his part.” Walker ventured that the downfall happened because Jimmy Swaggart Ministries was getting too big.

Lorraine Thomas had moved with her husband, a preacher (now deceased), to Baton Rouge from Arizona in September 1987, just months before the scandal unfolded. “God said, ‘Go there and lift Jimmy up because he’s going to go through a great trial,’ ” she recalled. All three said that they met with ridicule when they told others that they attended Swaggart’s church. “Is he still preaching?” friends ask incredulously.

As the klieg lights dimmed and the conversation drew toward a close, Whittenburg asked, “Do you mind if we pray with you over this article?” A small crowd encircled me and joined hands. “Lord, we pray that you would send your Spirit upon this man as he writes this article,” Walker intoned. “Help him to remember the things he should remember and forget the things he should forget.”

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THIS PICTURE? In the decade since the televangelist scandals we have forgotten some of the shame that was heaped upon evangelicalism in the 1980s, but evangelicalism itself, the most resilient and influential movement in American history, has managed to survive, even prosper. I wonder, however, if the fixation on the financial shenanigans and the sexual escapades of the scandals has allowed us to dodge some thorny questions. Surely the transgressions of Bakker and Swaggart were not that much more egregious than Pat Robertson accepting Rupert Murdoch’s millions for the sale of the Family Channel, a property that Robertson developed from the tax-deductible contributions of the faithful. A focus on the transgressions of Bakker and Swaggart deflects attention from theological issues surrounding televangelism. The obscene sums of money pouring into the televangelists’ coffers is an invitation to abuse, and we can only speculate on how much of that revenue has been diverted from local congregations.

Evangelicalism, with its relative lack of creedal formulas and the absence of strong ecclesiastical structures, moreover, has always been susceptible to the cult of personality, a weakness only magnified by television. Evangelicals once harbored a healthy—though, at times, excessive—suspicion of worldliness, but they too have been infected by the culture of celebrity. Although evangelicals have always been citational in the expression of their beliefs, the fixation on celebrity in the last couple of decades has produced an important shift. Evangelicals once referred directly to the Bible as the basis for their theology, but now, more often than not, the citation has been filtered through the celebrity preacher: “As Dr. Swindoll says … ,” or “As Dr. Schuller says … ,” or “Dr. Dobson believes that . …”

Finally, while only the most obdurate Luddite would deny that the gospel can be proclaimed over the airwaves, evangelicalism’s worship forms, with the overweening emphasis on the sermon and the relative neglect of the sacraments or the church as the body of Christ, has led some viewers to suppose that a Sunday morning in the easy chair might be the rough equivalent of an hour in the pew. Besides, those televangelists, with their high-tech graphics and their cuddly musicians, sure know how to put on a good show!

But no one, not even Swaggart with his remarkable artistry, has found a way to sustain the community of faith over the airwaves. Worship surely must be something more than watching a preacher trying to project bonhomie and intimacy into a television camera. Shouldn’t the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation mean something? Jesus took on a fleshly form, after all; he didn’t rent satellite time. The gospel itself was flesh and blood, not an image flickering across the television screen, the medium capable of such extraordinary deception. No, the gospel is tactile and visceral, incarnate, the very characteristics we celebrate in Holy Communion. Blessed are the present, Jesus seems to be saying throughout the New Testament. Blessed are the present, for they are here and not absent.

WHY JIMMY MAKES US UNCOMFORABLE Swaggart’s sermons and his autobiography are replete with references to the Devil and to darkness. He speaks of being “anointed by the Devil” as a young man, while playing the piano in a competition, and another time when the “darkened, oppressive forces of hell had been unleashed against me.” He wrestled with demons luring him to the movie theater and the temptation to follow his cousins, Lewis and Gilley, into the secular music business. But for every account of slipping into dark waters, Swaggart eventually claimed a victory.

“Jerry Lee can go to Sun Records in Memphis, I’m on my way to heaven with a God who supplies all my needs according to his riches in glory by Christ Jesus,” he declared after a bout of envy at his cousin’s wealth. “I didn’t know how to explain it, but I knew I had won a great victory over the powers of darkness.”

While preaching in Ohio on the camp-meeting circuit many years ago, Swaggart was awakened by a flash flood. The raging waters, he said, nearly swept him and his wife away, but God spared them. “The Devil had tried to take our lives, and I realized the struggles would become more intense as I moved forward with God,” Swaggart recalled. “For years to come, I would dream about struggling against that current and almost drowning.”

For more than a decade Jimmy Swaggart has been struggling against the current. But when he responds to his critics by saying that “as many scars as I have, another one doesn’t really matter,” I suspect he’s talking about something more than scorn and ridicule and declining revenues. When Swaggart refers to the “stygian night of darkness,” the reference is internal as well.

Perhaps that’s why Swaggart makes us uncomfortable. All of us wrestle with demons, whether we use that terminology or not. They may or may not be sexual, as with Swaggart, but from time to time we feel ourselves slipping into dark waters, and the undertow seems all too overwhelming. Swaggart, with his tears and his sweat and his tortured confession, seems all too human, and, let’s face it, we evangelicals prefer our heroes to be anodyne and in control, tidy and triumphant. Swaggart makes us uncomfortable by reminding us of ourselves, but rather than facing our faults, our fallenness, our humanity, it’s easier to change the subject and dismiss Swaggart with ridicule. More’s the pity, for it is only by gazing into the mirror of our own wretchedness that we begin to comprehend the magnificence of grace.

A decade ago, groping for an explanation for his transgression, Swaggart remarked, “Maybe Jimmy Swaggart has tried to live his entire life as though he was not human.” We’ve known about Swaggart’s humanity for a decade now, and when in the course of a sermon he segues into “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me,” some would dismiss that as contrived and disingenuous, just another part of his act.

I think he knows whereof he speaks.

Randall Balmer, professor of American Religion at Columbia University, is the author of Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: A Journey into the Evangelical Subculture in America.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.