In 1975, a British Columbia couple was among the few Christian families that adopted a Cambodian orphan of the infamous killing fields genocide.

But the life of their adopted son, Michael Senior, 23, was cut tragically short in July when a coup in Cambodia was accompanied by an outbreak of violence.

Airlifted out of Phnom Penh at the age of 13 months, Senior’s life had recently come full circle. In 1995, he returned to Cambodia and was teaching English in Phnom Penh, and his Cambodian wife worked for World Vision. With Senior’s death, his infant daughter, Nina, joins yet another generation of Cambodians whose families have been shattered by decades of bloody conflict.

“Michael was a miracle,” Judy Senior, his adoptive mother, told Christian Info News of Vancouver. “I know that God is going to use his short life for some good. Out of his death will come the life of God … the presence of Jesus in Cambodia.”

Cambodia is not only one of Asia’s poorest countries economically, it has also been a modern war zone since 1970. Following the costly United Nations- sponsored elections four years ago, Cambodia’s experiment in democracy has been precarious.

An unwieldy coalition government, led by co-prime ministers Prince Norodom Ranariddh and Hun Sen, attempted to rule Cambodia. But by mid-1997, tensions between the bitter political foes had reached the breaking point. Then, on July 5, taking advantage of Ranariddh’s absence from the country, the units of the national army loyal to Hun Sen seized control of Phnom Penh and most provincial areas. At least 35 people died in the fighting, including Senior.

DEPENDENT ON FOREIGN AID: Since the 1993 elections, the Cambodian government has been heavily dependent on foreign financial assistance. But following the coup, some countries as well as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund put aid programs in limbo.

The U.S. government’s Agency for International Development (USAID) has halted expansion of relief projects in Cambodia. Yet not all countries and not all relief agencies are doing the same. “If the British government had followed suit, we would have had to shut our larger project down,” observes Andrew Leigh of Christian Outreach, a British relief group. Shortly after the coup, 84 relief agencies urged the U.S. government to continue aid to Cambodia. “This is not the time to leave the Cambodian people in isolation,” says Rodney Page of Church World Service.

Some U.S.-based groups such as World Relief (WR), the relief-and-development arm of the National Association of Evangelicals, have been affected by USAID’s decision to delay funding for new programs.

WR president Clive Calver refuses to see USAID’s delay as a setback. “This can be the start of an era and not the beginning of a problem,” he insists. WR’s grant would have provided care to 24,000 mothers and children, and some of them face death without the assistance. “USAID has said the proposal we made was superb,” Calver says. “The reason they are not going to grant it is simply because U.S. government policy is not to give any new grants to Cambodia until after [next year’s] elections.”

NO WAITING AROUND: Faith-based relief-and-development agencies and Cambodian Christians have persevered in caring for the poor, planting new churches, and rebuilding villages in spite of the nation’s volatile politics.

It is quite possible that the elections long scheduled for next year will not take place due to Hun Sen’s firm grip on power. And if elections do occur, it is also quite possible that they will not be as free and fair as outsiders might hope. But relief agency leaders such as Calver are not sitting idly by as international policy and politics grind away.

WR has committed itself to raising $250,000 in private donations to finance its new program for Cambodian mothers and children for one year.

“As we’ve faced the challenge together, people have said, ‘Isn’t this better?’ ” Calver says, noting that more than half of the funds have been raised. “Without USAID, we can be more open about the gospel.” Federal restrictions, under the principle of church-state separation, do not allow faith-based organizations to use federal grants for any overtly religious activity. But such organizations are allowed to provide contracted services and programs as other secular, nonreligious relief groups do.

A COUNTRY WITHOUT A FUTURE? Cambodia is situated between Thailand and Vietnam. Geographically the size of Missouri, Cambodia’s closest historical equivalent is Haiti.

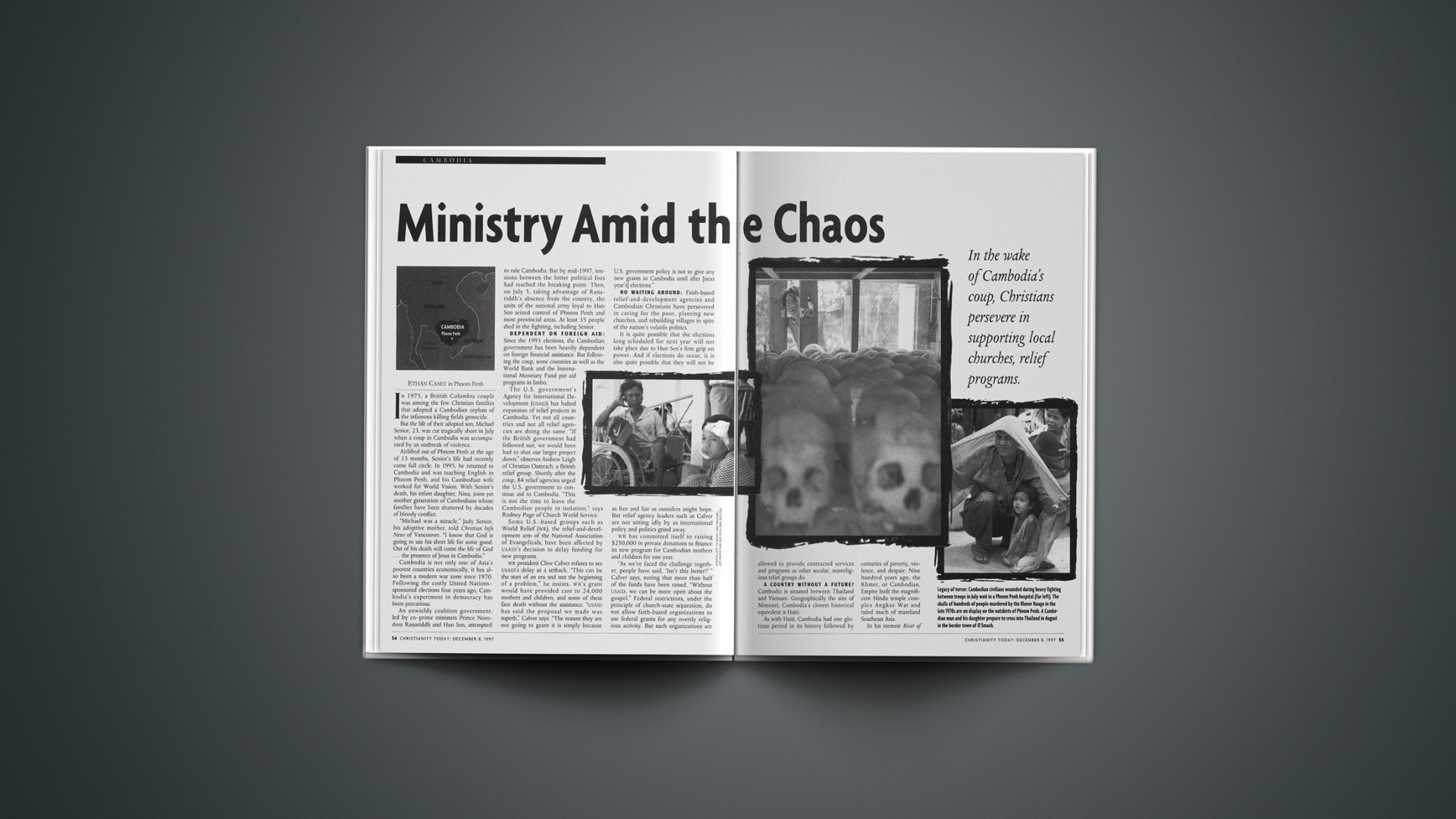

As with Haiti, Cambodia had one glorious period in its history followed by centuries of poverty, violence, and despair. Nine hundred years ago, the Khmer, or Cambodian, Empire built the magnificent Hindu temple complex Angkor Wat and ruled much of mainland Southeast Asia.

In his memoir River of Time, journalist Jon Swain calls Cambodia in 1970 “a country without a future.” The 1970 coup by Field Marshal Lon Nol and the Nixon administration’s airborne bombing to cover withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam set the stage for the 1975-79 rule of the Khmer Rouge or “Red Cambodians.”

During Khmer Rouge rule, 1.5 million people died from violence, starvation, or disease, and Cambodian Christians experienced a devastating setback. The World Churches Handbook estimates that the number of Christian congregations fell 80 percent, from 87 in 1975 to 17 in 1980.

In 1979, Vietnam invaded Cambodia and ousted the Khmer Rouge. But the United States, China, and Thailand, each for its own political reasons, all disapproved so much of the Hanoi-guided Communist government led by Heng Samrin and later by Hun Sen that they aided the now-rebel Khmer Rouge during another bloody internal war that finally ended with a 1991 peace agreement.

A brief period of relative peace, openness, and hope began with the 1992-93 United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia and ended abruptly in July. Christian and other relief-and-development agencies began trickling into Cambodia to work in areas such as health and literacy as early as 1980, but not until the United Nations period did their presence come to be strongly felt. Largely because of the millions of dollars in aid money from around the world flowing into Phnom Penh, this small, poor, and rough-and-tumble city now sports a thin veneer of prosperity in some quarters.

A SMALL, BUT STRONG CHURCH: In spite of their common purpose of helping Cambodia survive, secular and faith-based relief agencies do have tensions. Those tensions heightened in the wake of a Phnom Penh evangelistic crusade in November 1994. Texas-based evangelist Mike Evans was forced to flee a crowd of angry Cambodians, some of whom had traveled long distances from the provinces in the belief that they would be miraculously healed (CT, Jan. 9, 1995, p. 57).

“That set Christianity in Cambodia back quite a lot,” says Colin Radford of the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA). “For about 12 months, anything to do with Christianity left a bad taste in people’s mouths.” Despite the Evans incident and other difficulties, the country does have a small but strong Christian community. According to Joel Copple, country director for World Relief, there are about 450 known Christian fellowships in Cambodia and perhaps as many as 30,000 Christians. A Baptist Association formed in 1995, and it has grown to more than 40 churches.

Moeun Sany, a resourceful, smiling man who runs ADRA’s successful garden project, is one of 30 in the village of Tang Krossang in Kompong Thom province. Like many Cambodian Christians, he became a Christian in a refugee camp in Thailand in the early 1980s. “I think in the future the number of Christians will increase in Cambodia,” he says confidently.

BLESSING FROM A CURSE: As Christians in Cambodia have achieved some progress in rebuilding the church, they have gained a fresh understanding of the gospel’s durability. Cheryl-Kim Quillin, a 28-year-old American nurse in Tang Krossang, believes some Cambodians are more willing to examine Christianity now than before the genocide years, but she is disturbed by the implications of this.

“This is a positive for Christianity,” she says. “But it’s really saying that what used to hold together their religious system is totally broken. Many people would say God has made a blessing come out of a curse. And I believe that, too; but still, the tragedy of what has happened to the people.”

Quillin observed Cambodians’ openness to Christianity at first. “Part of it is their survival instinct,” she says. “[But] we have a very high fallout rate, because a lot of Cambodians get pressure: ‘To be Khmer you have to be Buddhist.’ ” In addition, she says some new converts are called rice Christians, who turn out to be motivated by a desire for material gain, not newfound faith in Christ.

STANDING UP FOR JUSTICE: If the country’s troubled history has made some Cambodians more receptive to the gospel, those missionaries who come to Cambodia to do church-based ministry also find themselves developing in new ways.

Quillin, an Adventist pastor’s daughter from Michigan, is but one example of how missionaries are changed by the circumstances in which they minister.

Quillin intended to do traditional missions work of church planting and evangelism when she came in 1994, but her supervisors instead refocused her attention into health-and-development work. “That forced me to become a professional,” she says now with satisfaction.

Much soul-searching and prayer led Quillin to the conviction that Cambodia was where she belonged, even before she had visited the country. “I have a very strong sense that God called me to work with Khmer people,” she says.

“Politically, I didn’t know anything about it before I came here. Now I’ve been changed forever. I want to stand up for their justice. I don’t want the gun to be the voice.”

THE CNN EFFECT: Even as some missions leaders have recommitted themselves to Cambodia, support from their home countries has been undermined somewhat by the intense media focus on violence within the country.

WR’s Copple believes that advances in news media technology have forever changed the environment in which relief-and-development agencies and missionaries carry out their work, especially when violence and politics mix. He says, “During the Vietnam War, you’d see it for ten minutes, then you wouldn’t see it again until the ten o’clock news. With CNN it’s just constantly in your face.”

Pierre Tami of Youth with a Mission (YWAM) agrees: “People see a tank and they panic. The perspective from outside is not objective.” Tami, who lives with his wife and three daughters in Phnom Penh, was in the thick of things the weekend of the coup. “We had tanks posted outside of our house,” he recalls. Tami sent all Khmer YWAM workers home that day and instructed the expatriate staff to buy three days’ worth of food and fuel to be sure they had adequate backup batteries and access to drinking water, and to stay at home and remain in radio contact with him.

The most immediate concern of relief agencies at the time was workers’ safety. “By the time we could get people out, it was obvious that there was no real need to get them out,” says Howard Jost of Church World Service. “It did seem that if the fighting got stronger again, we could have gone by road to Vietnam.”

HOW SOVEREIGN IS GOD? In times of crisis, a perennial dilemma for overseas missions personnel is that they may be evacuated in a country’s time of greatest need.

After ADRA country director Murray Millar decided that foreign dependents should leave the country, Quillin recalls, “We were praying, and the thought struck me that we have passports; we can leave. These people can’t leave.”

ADRA staff had the added, coincidental concern of hosting 28 visiting Adventist leaders from the United States.

Millar himself had decided to leave the country a few days after the coup, but a sleepless night convinced him he had made the wrong decision. “It’s like the captain of a ship staying on the ship until the end,” he says. “That was for me an incredible lesson; it was like I’d died and come back to life again.”

The experience left him with strong feelings about what is and is not appropriate action at such a time. “In analysis of those who left the country, it is astounding how many Christians were [in] the exodus,” he wrote in a circular letter soon after the coup. “Khmers are now questioning our trust in God.”

Millar stresses, “I don’t want to be misunderstood as saying a Christian should always stay right to the end. The conclusion I’ve reached is that we shouldn’t be influenced by outside opinion.”

Leigh of Christian Outreach happened to be on vacation in Thailand and tried to return to Cambodia while others tried to flee. “I’m the country director,” he says. “If there is a crisis, this is where I should be.” Leigh arrived July 11 on the first commercial flight into Phnom Penh after the coup.

A DEFINING MOMENT: The coup was a defining moment for individuals and governments concerned with Cambodia. While some human-rights activists are calling for an international boycott, others are more centered on what can still be accomplished. “That the world is evil is an old story,” says YWAM’s Tami. “We are not here for politics. It is not a matter of whether we like Hun Sen or not. Even if [Khmer Rouge leader] Pol Pot came, we would still stay.”

The United States’ stance on restoring aid to Cambodia includes the phrase “pending free and fair elections.” But as with Haiti a few years ago, Christians in Cambodia are keeping their focus on ministry, not on the ebb and flow of politics.

Millar, a New Zealand native, says, “There’s a stark reality here. To me the real power of Christ is when he comes in and helps people to be themselves. It’s my conviction now that we’ve got to help people to think, to see possibility. And that’s got to be done in their own context, not with a big UN program.”

Tami says, “The question is not whether we’re going to have problems or not. The question is how we are going to solve them.”

Copyright © 1997 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

December 8, 1997 Vol. 41, No. 14, Page 54