It was the summer of 1972, a few months after my conversion at the age of 16, when I confronted, firsthand, Bill Bright's evangelistic mission. I had taken a Greyhound bus cross-country from Ohio to Dallas, Texas, to attend Explo '72, Campus Crusade for Christ's (CCC) week-long evangelism training conference. There, through daily workshops and evening praisefests at the Cotton Bowl, the zeal of the Jesus freaks was effectively harnessed. We were trained to use the Four Spiritual Laws (Bright's evangelistic formula for pitching the gospel) and then unleashed to advance in an evangelistic blitzkrieg in our hometowns.

I broke in this innovative system on an easy target—my little sis (aged15). I hoodwinked her into meeting me on the swing set, and then I laid out God's blueprint:

—God loves you and offers a wonderful plan for your life.

—Man is sinful and separated from God, thus cannot know and experience God's love and plan.

—Jesus Christ is God's only provision for man's sin.

—We must individually receive Jesus as Savior and Lord.

Got it?

Without hesitation she told me she wanted to "receive Christ" and "pray the prayer." I read the prayer from the booklet; she echoed. She cried; I cried.

I thought, This is easy.

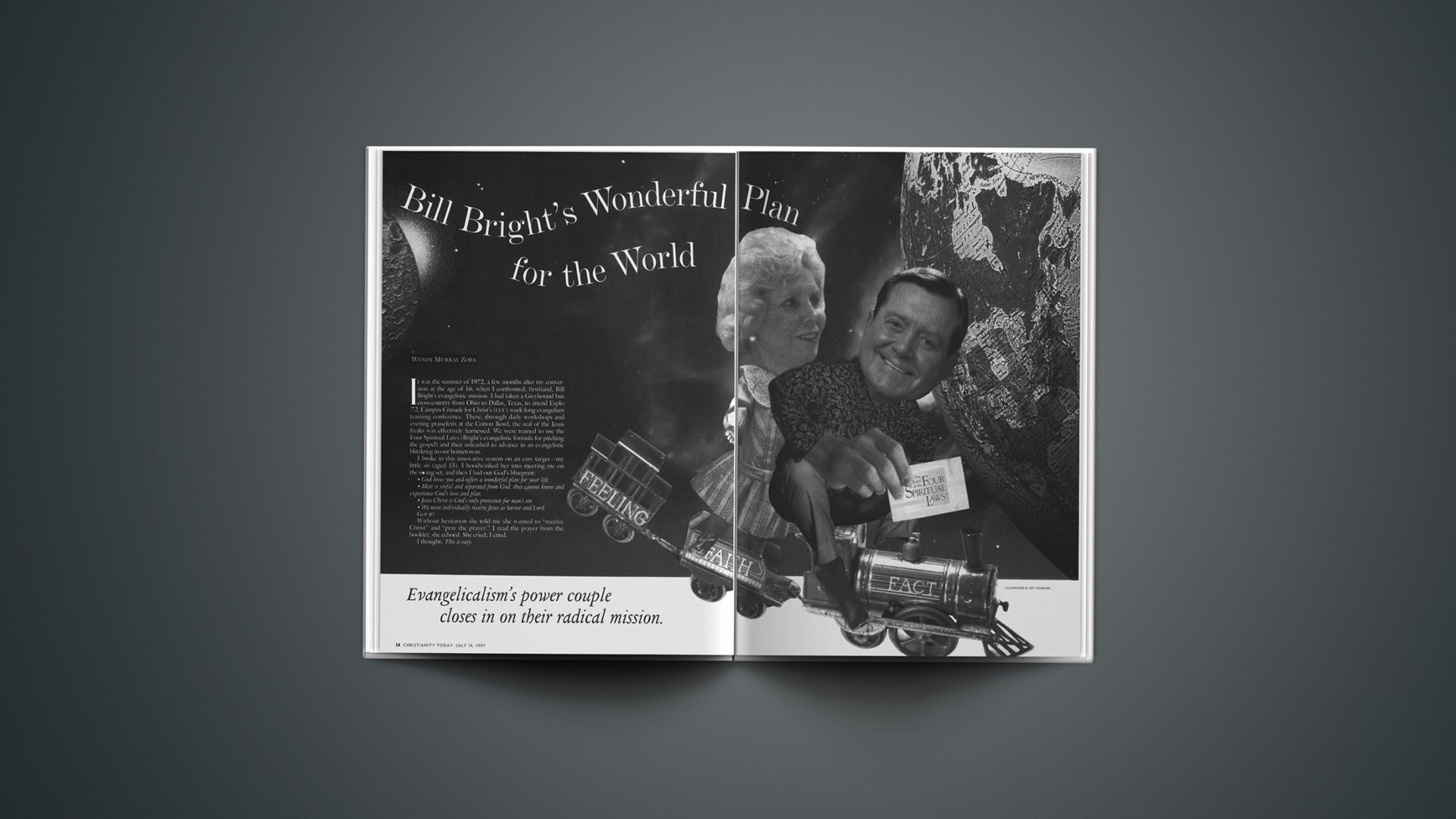

We finished with a recitation of the principles outlined in the back illustrated by the Fact-Faith-Feeling train. The fact of what God has done in Jesus is the engine that drives the train; fact pulls faith behind it; feelings take up the rear in the caboose. ("Our feelings—thecaboose—must never drive the train," I said.)

That encounter saved my sister.

Fifteen years after that Ohio summer she and I shared another life-changing moment. We buried her first-born child, who died of head injuries sustained in a freak accident. She died the day before her second birthday. The birthday cards were already in the mail.

During those dark days I pleaded with God that the faith my sister owned that day on the swing set would hold up.

In the end, it held. (Though her understanding of God's "wonderful plan" moved into a new dimension.)

I have never dismissed the value of the Four Laws. I used to keep one copy in my wallet—just in case the opportunity to witness to somebody presented itself. But the booklet became so tattered and worn (from being dutifully kept but never used), I ended up throwing it away. I guess I stopped thinking about my Christian witness in terms of laws, plans, and trains.

In a similar vein, segments of evangelicalism have felt ambivalent aboutthe Bright blueprint for kingdom building. The misgivings focus on three fronts: CCC's "simplistic" theology; the "mass marketing" approach to evangelism; and the embrace of pragmatic means to fulfill the inspired end of reaching every person with the gospel.

Theology. Richard Quebedeaux notes in his biography of Bill Bright (I Found It, 1979) that many dismiss his approach as "crassly superficial." Former CCC staff worker Peter Gillquist leda handful of Crusade staff (and hundreds of other evangelicals) to Eastern Orthodoxy in the late eighties, citing a hunger for "something more" than the "reductionism" of Crusade-type evangelicalism. Ole Anthony of the Trinity Foundation points out: "The Laws offer nothing about the cost of discipleship." Mark Noll writes in The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind that Bright and other "popular authority figures" have contributed to an intellectual environment in evangelicalism today that is "naive, inept, or tendentious." Many Christians can't abide reducing Christian doctrine to simple how-tos.

Mass marketing. Bright is a businessman. His business acumen has emboldened him to lurch ahead where many evangelicals fear to tread: He has wedded spirituality and marketing principles. J. I. Packer calls Bright "God's entrepreneur to middle America." "Some brilliant people can see their wayto a formula that fits almost everybody," Packer says. "Henry Ford did it with the Model T; Bill Bright did it with the Four Spiritual Laws." Bright understands America's appetite for a simple message with straightforward appeal. So the gospel presentation he has fashioned can be mass produced, expeditiously disseminated, and proficiently advanced.

But he is not just a businessman.

Bright is convinced that God has given him the mandate to reach "every singlehuman on earth" with the gospel. Campus Crusade is the vehicle to that end. So he is also a visionary. And the wedding of these two forces can, at times,result in the passing over of the mundane details of ministry management and the sometimes faltering human element. And this introduces the third area of ambivalence.

Pragmatism. Campus Crusade has one mission: to get the gospel to every human on the planet. It is fueled by visionary zeal, plotted according to marketing principles, and executed by a multimillion-dollar ministry that includes over 14,000 workers. So things can, and do, go wrong. Bright finds himself in the center of painful controversies, some attributable to his own missteps, some not. Good people are sometimes swept up and away in the whirlwind of reaching the larger goal.

All of these, for good or ill, are parts of the picture of Bill Bright. Yet there is another side of him that completes the picture.

Entrepreneurs are supposed to have one thing on their minds: profit margins. While Bright epitomizes the hardball business wizard in his orchestration of CCC's mission (Bright raises more money than you or I can dream about—Packer quips; "Bill stage-manages mass money"), on a personal level, he defies his entrepreneurial persona by renouncing personal wealth and material gain. In fact, his latest preoccupation is calling American Christians to self-denial, to repent through prayer and fasting.

So the businessman advances the cause by shrewdly applying market principles; the visionary defines his motives by denying self-gratification and greed, the very engines that drive our consumer culture. The visionary sees the landscape of possibility by the power of God, the businessman translates that vista into real estate. He rubs elbows with multimillionaires like the Bunker Hunts of the world, though his annual income is comparable to that of a McDonald's manager.

Whether because of, or in spite of, Bright's approach, God's blessing is evident in his life and on his work. Campus Crusade's marketed gospel, billboard tactics, and no-holds-barred global mandate are changing the world. Superficial, reductionist, tendentious or not, God used the Four Spiritual Laws to save my sister.

Rancher Turned Visionary

"Every farmer is a fool [dramatic pause] for who will stand by year after year and see his soil washed away without doing anything about it?" This provocative elocution won the young, lean, bareback bronco-riding Oklahoman William R. Bright (then 18) the national Future Farmers of America oration contest in 1939. The speech, entitled "I Dare You," exhorted farmers to take advantage of the various methods of soil rotation (land terracing, treated soil, and fertilizer) to preserve the viability of their land. "Two farmers could be side by side—same soil, same sun, same rain; one is poor, the other is rich," Bright, now 75, recalls. "There's a difference in the way they do things. My challenge to them was: 'I dare you to be different.' "

Bright took his own advice. He, along with his wife, Vonette, launched Campus Crusade for Christ 46 years ago on the campus of UCLA, their first meeting targeting a sorority known as the "house of beautiful women. "Today the organization employs 14,200 staff along with 163,000 volunteers in 167 countries. The Jesus film alone (the life of Jesus on film, based on Luke's gospel), created and produced by Crusade, has been viewed by over 850 million people in 219 countries in 400 languages. (According to their calculations, "tens of millions" have "responded" to the message.) U.S. News & World Report ranked Campus Crusade as number one in America's "biggest" religious charities in 1995, outranking in total income the Christian Broadcasting Network, Focus on the Family,the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, and Wycliffe Bible Translators.Money magazine (1993 and 1995) labeled it the most "efficient" religious organization in the U.S. (measured by the percentage of the charity's incomespent on programs). In 1996 Crusade's "world revenues" (including U.S. andinternational ministries) totaled nearly $300 million.

According to the Brights' estimate, CCC has helped reach at least 2 billion people with the gospel. They know this because, for years, Crusade quantified their results by tracking numbers, a method they no longer use (to Bright's regret—"It's important for account ability"). As newspaper editor and former CCC staff worker Ken Sidey says, "It ishard to go anywhere in Christian circles and not meet someone who has been touched by Campus Crusade for Christ."

"We are dedicated to using the most strategic, efficient means available to give every resident of planet earth the opportunity to say 'yes' to Jesus Christ."

Still, Bright is self-deprecating. He calls himself a "puny termite somewhereout in space." In his acceptance speech when he received the Templeton Awardfor Progress in Religion last year, he recounted how, before he became a Christian, he was driven by "selfish goals—materialistic pursuits." All that changed after he surrendered his life to Christ at the age of 23. Afew years after his conversion, he renounced his worldly inclinations anddrew up a written contract with the Lord, proclaiming, "I am your slave."Since then, Bright's spiritual sensibilities have been consistently quickened with "overwhelming impressions" from God.

In July 1994 the Lord "impressed" upon Bright to pray for revival in America. He prayed, "Lord, I'll fast for 40 days, but you'll have to help me." The third week of that fast he sensed that God heard his prayers and promised to send revival. "The Lord impressed me that he was going to send a revival that would be the greatest spiritual harvest this nation and the world have ever seen. But first," he says, "there had to be a humbling and a brokennesson the part of believers." Bright is not "given to prophecy" ("I'm a Presbyterian"), but he would "stake his life" on these promises. His confidence rests on the simple fact that this is what God "told" him.

Confections to Convictions

Bill Bright grew up "in the saddle," the sixth of seven children on a ranchin Coweta, Oklahoma. His grandfather had been a pioneer in oil, so the family was very prosperous, though not pampered. The Bright ranch was also the "entertainment center" of the surrounding area, with a constant flow of people either soliciting his father for advice on cattle or attending one of many watermelon and ice cream parties the family sponsored.

According to Vonette, Bill inherited the "finer fibers" of a spiritual nature from his mother, Mary Lee Rohl Bright, who, says Bright, "was truly a saint, though I didn't appreciate that when I was growing up." He credits her strong character for many of the spiritual qualities he would eventually adopt.

He graduated from Coweta High School in 1939 (having developed his own herd of registered short horn) and went on to study economics and sociology at Northeastern State College in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. After graduating in 1943, Bright served for a year as part of the extension faculty for Oklahoma State. Then he moved west to seek his fortune in California.

Before "making it big," however, Bright faced an unusual test. "The day Pearl Harbor was bombed, we all signed up for the military," he says. "They knew I had a perforated eardrum, and they rejected people with perforated eardrums because of poison gas. So I went to the air force, the navy, the marines,the coast guard—anything to get in. I had three brothers and all of my fraternity brothers in the military. I was the only one left." He went to California with the hope that he could overcome the obstacles he faced in his small town and find his way into the service there.

"I can remember watching Bill during that time," says Vonette. "His face was red all the time. He was embarrassed to be 4F. It was the first thing that he'd ever wanted that he was not able to accomplish."

His mother's prayers began to catch up with him on his very first evening in L.A. While out looking for a good time, he picked up a hitchhiker who turned out to be a member of the Navigators and, worse, the housemate of Navigators founder Dawson Trotman. He invited Bright to dinner with the Trotmans. Bright became positively predisposed to Christianity as a result of the Trotmans' gracious demeanor. Later that same night he ended up at a party given by Dan Fuller, son of radio evangelist Charles E. Fuller (and soon-to-be founderof Fuller seminary).

Bright had no interest in God or related subjects at the time and by now had launched his own business, Bright's California Confections, purveying "epicurean delights"—fruits, candies, jams, and jellies. But the pull toward faith became more acute when the elderly couple he was living with relentlessly urged him to come to their church (First Presbyterian of Hollywood) and hear their pastor, Louis Evans, Sr., preach. One Sunday, after a trail ride, he felt the pull to slip into the service ("smelling like a horse") to hear Evans preach. Shortly after that, a young woman "with a come-hither smile in her voice" invited Bright to a church-sponsored party, which introduced him to the church's social scene. He thought, if nothing else, becoming part of the church would expose him to the rich and famous who attended.

But his church attendance carried the additional effect of introducing him to the solid, radical declarations of the teacher of the college students there, Henrietta Mears. In the spring of 1945, when Bright was 23, Mearsspoke about Paul's conversion on the Damascus Road. He recalls: "She ended her message by saying to us, 'When you go home tonight, get down on your knees and say with the apostle Paul, Lord, what wilst thou have me do?' "

There were no bells and whistles when Bright prayed this prayer. But, he says, "The Lord knew my heart; he knew I was sincere, and he changed my life."

He decided that he needed all available information pertaining to this new adventure in faith. So he left Bright's California Confections under the oversight of a manager, and in the fall of 1946 he went east to attend Princeton seminary. He returned less than a year later: "It wasn't a happy situation. You can't run a successful business that far away." He moved back to southern California and enrolled as a member of the first class of a fledgling seminary named Fuller.

It was also in 1947 that he joined Mears's discipleship group known as "the Fellowship of the Burning Heart." Through this connection he and several friends, under the guidance of Mears, pledged "absolute consecration to Christ." This marked the beginning of the end of Bright the entrepreneur of epicurean delights and the birth of a new Bill Bright—the entrepreneur of the gospel.

A Tortured Affair

Vonette Zachary also grew up in Coweta. Despite their age difference (heis five years older), Bill and Vonette remember keeping tabs on one another.Her first memory of young Bill was when her family attended one of the Brights' famous ice cream socials. The 11-year-old Bill stood in his bare feet and overalls to open the gate for guests. "You could pick him out of the crowd," she says, "standing with one hand in his pocket, just very confident." "There was no heart throb," she says, "but I can tell you where he stood waiting for the school bus."

The relationship lay dormant until the summer of 1945 when Bright, now livingin California, took his sister to see Diana Lynn perform. "She reminds me of the Zachary girl. What's happened to her?" he inquired. His sister informed him Vonette had just finished her first year at college in Texas. "So I dropped her a line the next day."

The letter contained three short sentences, but the big 'B' on the burgundyand gray number-10 envelope made an impression. To his three sentences Vonette responded with ten pages, and that launched what became almost a year of daily correspondence between them.

In the spring of 1946, the 24-year-old Bright returned to escort Vonette Zachary to a ball. "We had been corresponding a lot. So I was pretty sure that I was in love," she says—though she wasn't expecting a marriage proposal on their first date. (Bright recalls this daring move: "I sensed the Lord telling me that this was the person I was to marry.") The following fall,when Bright went to Princeton, he promised her his fraternity ring.

But a glaring inconsistency in their relationship began to develop. "Vonette was not a believer," says Bright. "She'd grown up in the church, so she thought she was." In fact, Henrietta Mears, who didn't know Vonette, thought Bright was "throwing his life away" on this hometown girl.

At the same time, Vonette thought he was becoming a fanatic. "I was getting all these biblical references from him all the time. He was going down and preaching on Skid Row, taking teams into the jails and road camps. The only people that I knew did things like that were Pentecostals, who seemed to me straight-laced, sober, and sad," she says.

At about this time a young starlet "made herself very available" to Bright and followed him out to Princeton. The letters soon stopped, and the fraternity ring was not forthcoming.

In the meantime, a man whom Vonette had been casually dating fell in love with her and once refused to leave her dorm until she would agree to marry him.

"I cannot tell you that," she said.

He rejoined: "Well, just tell me that you love me."

She thought she could, in truth, say that she "loved" this man (kind of):"He was a great guy; he was very respectful toward me." So she mumbled the words he longed to hear, and he went bounding down the stairs, "excited to death."

"I shut the door to the dorm, and I thought, 'What in the world have I done?'"

This crisis convinced the lovesick Zachary girl that her heart belonged to Bill Bright and that a chasm had to be crossed for this relationship to succeed. So she prayed and asked God to intervene.

Bright came to see her on campus that spring (1947), and that began the restoration of the relationship. By the fall she was wearing the long-awaited fraternity ring, and by the end of the year she had an engagement ring.

Mears asked Bright, "Who is this you've given a ring to?" Bright thought it was time for these two to meet, so after Vonette's graduation from college in the spring of 1948 she attended a college briefing conference with Brightat Forest Home, Henrietta Mears's retreat center.

"It was there that Henrietta Mears led me to the Lord," says Vonette. The Brights were married in December and settled into their new life with all the worldly possibility that cattle herds, confections, and oil ventures promised.

How to Reach Every Human?

The Brights drew up lists outlining what they wanted out of life. Reading them they recognized that their desires were largely directed toward worldly gain and comfort. They reassessed their lists in light of their blossoming faith and compiled new ones. This time their agenda included things like "living holy lives," being "effective witnesses" for Christ, and "helping to fulfill the great commission in their generation."

They then consecrated these priorities in the form of a "written contract" with the Lord. In this document they renounced materialistic inclinations, surrendered their lives, and took on the status of "slaves" to Jesus Christ. The contract was a "transaction of the will," Bright says. "There was no particular emotion behind it."

After this "transaction," Bright received what he says was an "overwhelming impression" from the Lord: "I was studying for one of my final exams in seminary. It was about midnight, and in an unusual way, God met with me. He gave me my marching orders. He told me what I was to do in broad strokes as on anartist's canvas. That night he gave me the broad picture of the world."

He shared this "impression" the next day with his Bible instructor, Wilbur M. Smith, who felt convinced that the vision was "of God" and told the young Bright that he would join him in praying about it. The next day in class, Smith handed Bright a small piece of paper on which were written "CCC/Campus Crusade for Christ." ("God had provided the name for my vision.")

"The longer I worked with the intelligentsia, the more I realized the necesity of developing simple how-tos for the Christian life."

In Henrietta "Dream Big" Mears fashion, the Brights took up the challenge (which became the CCC motto) to "win the campus to Christ today, win the world to Christ tomorrow."

Bright promptly dropped out of seminary ("Layman status has always worked to a great advantage in my ministry"); sought the counsel of other Christian leaders (including Wilbur M. Smith, Henrietta Mears, Billy Graham, Richard Halverson, Dawson Trotman, Cyrus Nelson, Dan Fuller, and J. Edwin Orr); started a 24-hour prayer vigil; and targeted the UCLA campus as CCC's first mission field.

Crusade's humble beginnings in 1951 centered on Bright's one-on-one ministry of evangelism and Bible studies targeting the "best and the brightest" onthe campus of UCLA (which explains why the first meeting met at the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority house—"the house of beautiful women"). The reach-the-world mandate accounts for this strategy: The "best and the brightest" would emerge as tomorrow's leaders who, in turn—once they were won for Christ—would influence others exponentially. (The "beautiful women" did have the effect of attracting inquiring men to CCC meetings.)

During the first year, the Brights found themselves without home and headquarters when their rental situation fell through. Again, Henrietta Mears entered the picture. She had a predicament of her own: her sister, who had run the home they shared, had recently died, and Mears wanted someone to live with. To answer both needs, she purchased a mansion only a few blocks from the campus and shared it with the Brights. The main dining room could seat 300people, so it was an optimal facility for housing what was becoming a burgeoning ministry. "We saw many people come to the Lord there," Bright recalls.

The ministry spread as students were won to Christ in herds; new staff jumped on board; ministries opened up on new campuses. In 1958 they moved their headquarters to Mound, Minnesota, where a pocket of land had been donated to them. When the first brutal winter dealt them 30 days of 30-degrees-below-zero temperatures, they were grateful when the townspeople offered the ministry "no encouragement" to expand.

By 1960 the ministry had expanded to include 40 campuses in the U.S. and overseas ministries in Korea, Pakistan, and Mexico. With the Minnesota property curtailing expansion, they set their sights on California, where Bright soon received another "overwhelming impression" about where to relocate: "The impression that God wanted this [Arrowhead Springs] facility for Campus Crusade was so real that almost every day I found myself expecting a telephone call from some person saying that he … would purchase it for us," he writes in his book Come Help Change the World. The call finally came—inpart. A significant portion had been promised by a donor if the balance ofthe $2 million purchase price could be raised.

To make a long, nail-biting, midnight-phone-calling story short, the Lord enabled Crusade to purchase the abandoned health spa and resort near San Bernardino, though some of Bright's key financiers jumped ship in the process. "They thought I was loony to go ahead with it," says Bright. One of Crusade's biggest givers and most loyal friends told him after seeing the property: "If you buy this property, I will never give you another penny." (Says Bright: "I think he missed a great blessing.")

The Spiritual Pitch

As the campus outreach was becoming fully operative, Bright realized that his growing team needed a uniform, accessible approach to communicating the gospel message—"a spiritual pitch," as he called it. The system he devised has come to be known as the Four Spiritual Laws, though at first he simply had his staff people memorize these general principles. (They were published when a businessman asked if he could make this presentation available to anyone, not only CCC staff.)

Bright calls the laws a "positive, 20-minute presentation of the claims of Christ: who he is, why he came, and how one can know him personally." He calls them a "harvesting tool," protesting that people who criticize this method are "hung up" about the fact that "harvesting" neglects "fertilizing" and "watering." But, he says, "those who find fault with the Four Spiritual Laws and other so-called simplistic approaches are people who don't recognize where the masses are."

"I never put on an act. I'm just Bill Bright. I'm to cast my cares upon him. And, of course, I have a few thousand of those."

By seizing the initiative to confront "the masses" with the gospel, the Four Spiritual Laws accomplish the first of three imperatives that define the Crusade mandate: win, build, send. Peggy Wehmeyer, religion reporter for ABC's World News Tonight, recalls the time during her sophomore year at college when she was "won" by Vonette's visit to the campus. Out of the blue, Vonette approached Wehmeyer and asked: "And are you a Christian?" The shock of that pointed question caused Wehmeyer to pause: "I said I wasn't sure." Wehmeyer is convinced that Vonette's initiative changed the course of her life: "If it weren't for Campus Crusade, I can't see my Christian life ever getting rooted."

Once a person is "won" to Christ, the Crusade staff person then seeks to "build" that person's understanding of the Christian faith through a systemized study of the "basic principles." Vonette's early campus Bible studies were the precursor for this "building" phase, which is based upon and supplemented by the "transferable concepts" (TCs), published by CCC in ten booklets. A transferable concept is "an idea or a truth that can be transferred or communicated from one person to another and then to another … without distorting or diluting its original meaning. "Growth in discipleship thus became a regimented process.

The TCs include such topics as "How You Can Experience God's Love and Forgiveness"; "How You Can Be Filled with the Holy Spirit"; "How You Can Be a Fruitful Witness." They are handles by which new Christians can grasp key Christian principles. Says Vonette: "If you study the material, you will know the basics of the Christian faith on each subject. We think believers ought to know how to express their faith to another person. It becomes a ministry of multiplication." And on it goes: winning, building, sending—an indispensable sequence if every human being on earth is to be reached with the gospel.

When the Vision Breaks Down

There has been some frustration both within the ranks and without because of Crusade's highly structured methodology for nurture and discipleship. Kelly Hardman, a former CCC worker who holds the organization in high regard, points out that the "highly trained curriculum" was the strength of the organization but that it "can be so 'by the book' that it does not take into account that people are different." She found that some of the people she shepherded had deep emotional dysfunctions and so would get waylaid in the build-ing (nurturing) phase, deterring them from being sent to win and build others. "The mechanism isn't prepared for that," she says. "I felt torn between who I should be spending time with and what my job description was."

On another front, an ideological skirmish erupted in the seventies when Jim Wallis, editor of Sojourners, cowrote an article with Wesley Granberg-Michaelson asserting that Bright was embroiled in a plan to use his ministry to achieve right-wing political ends. Bright had launched the "Here's Life, America" campaign as an attempt to turn the tide of cultural and moral decay. By means of billboards, bumper stickers, and massive phonecalling (using the teaser "I Found It" to promote conversation), CCC sponsored a massive effort to "saturate the United States with the gospel."

At the same time, Bright was heavily involved in networking through the politically conservative Christian Embassy in Washington, whose members had similar concerns about the nation's moral condition. Wallis and Granberg-Michaelson felt that Bright had indiscriminately mingled his evangelistic vision with the political goals of the newly forming Religious Right.

Bright did not help his own cause when he endorsed the book In the Spirit of '76 ("a handbook for winning elections") published by politically arch-conservative Third Century Publishers. He later admitted that he had never read the book—it had been commended by a staff worker—and that he didn't know what Third Century Publishers was about until he read the Sojourners article.

Bright denied being part of any political scheme, and today Wallis and Bright have grown to understand and appreciate each other's respective callings. Wallis recognizes that Bright's flirtation with political involvement inthe seventies was driven more by evangelistic fervor than by political ambition. And he also believes that the controversy helped nudge CCC toward what has become a standard operating principle not to politicize itself. "Bright moves in [politically conservative] circles," Wallis says. "But I'm not aware that CCC has aligned with any of those organizations."

In the mid-1980s, Bright undertook a project that he felt sure was another vision from God. He wanted to build the International Christian Graduate University—a "Christian Harvard," as a former CCC person put it, and he poured a great deal of the ministry's time and resources into the project.

They initially purchased 5,000 acres in the La Jolla Valley near San Diego for $27 million, without use of Crusade funds. They established a for-profit subsidiary, University Developments, to oversee the project. The mayor at first assured Bright that they could begin building within 18 months of the purchase, and then, later, the San Diego City Council approved the general plans. However, when a new mayor was elected, concern arose that the university and its attendant community would not be compatible with the county's slow-growth zoning policy. Zoning delays ensued over the next few years, so Crusade found it necessary to use its funds to cover the interest and principal payments. When the project was finally put on the ballot, voters turned it down 56 to 44 percent, despite the backing of business and evangelical leaders.

To cut their losses, Crusade was forced into Chapter 11 protection (court-supervised reorganization under the Federal Bankruptcy Act). Says Bright, "I had to question the Lord: Did I misunderstand you?" Ken Sidey says this is an example of where "the miracles didn't happen" for a Bill Bright vision.

Today, however, Bright says, "We are praising the Lord that he didn't allow us to build there." He says the value of the Crusade interest in the sameproperty today far exceeds the investments that were made in the eighties. And the institution he dreamed about is being realized in the form of a "university without walls" capitalizing on new computer technologies. "What we originally planned has been multiplied from what would have been thousands to millions of students," he says.

An Ever-Widening Net

But by no means was it all bad news during these formative decades. There were many high points, one of which was Vonette's finding her niche in the ministry. In 1972 she organized a prayer rally to which she invited women from all over the country to join in prayer for the nation and, more particularly, Explo '72 (7,000 women showed up). This success spurred her to organize gatherings all over the country, which became known as the Great Commission Prayer Crusade of 1972. "The greatest contribution that I've made had to be this call to prayer when there were so few leaders mobilizing people to pray."

This catapulted Vonette into a leadership role within the larger evangelical community. She became a member of the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization and served as chairperson of the Intercession Working Group from 1981 to 1990. She helped found the National Prayer Committee and served for nine years as chair of the National Day of Prayer Task Force. She helped draft legislation, which both houses of Congress unanimously approved, setting aside the standing date for the National Day of Prayer.

The success of Explo '72, which energized and mobilized 80,000 teens and college students from all over the country, was followed by an even larger showing at Explo '74 in Seoul, South Korea. More than 300,000 attended this conference, which mobilized national church leaders from all over the world to pursue evangelism. CCC was casting an ever-widening netas they implemented their global mission.

One-on-one ECs (evangelistic contacts) and small-group Bible studies on college campuses remained the heartbeat of the organization. Butas momentum was building, CCC expanded into a seemingly endless roster of new and diverse ministries to complement the evangelistic effort.

The Jesus film is one of CCC's crowning successes, having been projected on outdoor movie screens in just about every corner of the planet. Several years ago in Peru, for instance, during the insurgence of the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), a Wycliffe couplewas traveling to show the film in a village. Their vehicle was intercepted by the Senderos, and they feared for their lives (with just cause). Instead of killing them, however, the terrorists decided to seize their equipment, including the film projector. The husband boldly suggested that they might as well take the film reels too.

Some time later, a man contacted them and reminded them that he had been among the Senderos who had robbed them. He told them they watched the film seven times (out of sheer boredom), and some had been converted through it. He came to apologize and to tell of his ministry in preaching and evangelism.

"If you're going to join Crusade staff, you're joining a revolution."

There are stories like this associated with every arm of Campus Crusade's national and international ministries. The Andre Kole ministry uses Kole's illusionist skills (which have been likened to David Copperfield's) to stupefy audiences while weaving a gospel message into his performances. The Hollywood ministry reaches out to the Bel Air glitterati; the Josh McDowell ministry coordinates "morality campaigns" for young people and "truth campaigns" through McDowell's apologetics talks; Student Venture, CCC's high-school outreach ministry, follows the same blueprint in local high schools that is used on college campuses; Justicelink equips volunteers to minister in prisons; Prayer Works serves as a resource for local churches wanting tomobilize prayer ministries; Priority One Associates develops Christ-centered business leaders through luncheons and speakers; SOLO (Singles Offering Life to Others) networks with local churches to coordinate conferences, small groups, and outreach to singles; Here's Life, Inner City partners with urban centers in meeting the physical and spiritual needs of the urban poor; Women Today International, through a daily radio program (Vonette's latest undertaking), encourages and equips women in their respective callings, domestic or professional.

Campus Crusade was a charter member of the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability and publishes an annual audited financial report that is open to public scrutiny. In 1996 Money ranked CCC fourth overall in terms of bang-for-buck charities, and first among charities designated as "religious" (as opposed to "humanitarian").

All CCC staff workers raise their own support, 12 percent of which is channeled into the ministry (5 percent to overhead; 5 percent to overseas ministries; 2 percent to U.S. ministries, focusing on supporting minorities on staff). Bill and Vonette Bright, too, raise their own support and between them earn $48,000 ($29,000 and $19,000, respectively). Bright relinquished his Templeton prize money (in excess of $1 million) for the purposes of developing the ministry of prayer and fasting. He recently liquidated $50,000 of his retirement funds to help start up a training center in Moscow. All royalties from his books go to Campus Crusade; he does not accept speaking fees and has no savings account (though Vonette has a small one). The luxury condo they live in was donated to CCC (they pay $1,000 a monthrent). They do not own a car, and they have no property.

New Life 2000 is the latest dream child in fulfilling their evangelistic mandate. "We've divided the world into 5,000 regions with populations of 1 million each," says Bright. Then, through showing the Jesus film and airing translated radio broadcasts of it, coupled with massive mobilization of ministry teams, Bright hopes to penetrate even the most obscure corners of the planet. "We've taken the Jesus film into places where they've never seen a white man, or a movie of any kind. And 45 to 50 percent of them are accepting Christ," he says.

Crusade is targeting every household in the U.S. in an effort to get the Jesus video (a shorter version of the Jesus film) into every home by the end of 2000. Says Steve Douglass, executive vice president of Crusade's U.S. ministries, (who also holds degrees from Harvard and mit): "God called us, we think, to put a video in every home. We've knocked on 2.2 million doors, and almost a million people have indicated decisions for Christ. Bill said, 'That's good. But that's not all God has.' " (There are still 100 million doors to knock on.)

"We're ending this millennium, and people are expecting something wonderful to happen," says Bright. "We have momentum, and if we don't harness every opportunity, we'll fail—the Great Commission won't be fulfilled, and people will drift away. We are challenging tens of thousands of people not to make any plans but to help fulfill the Great Commission by the end of the year 2000."

Bright hopes that his life's work will culminate with the realization ofthe World Center for Discipleship and Evangelism in Orlando, which broke ground this spring. This campus, being built on 285 acres of donated land near Lake Hart, will house an operations and administrative support center (the "nerve center for global telecommunications"); a visitor's center (to "immerse friends of the ministry, prospective donors, staff, media representatives, and curious visitors in the story of the gospel and Crusade's mission to proclaim it to the world"); a retreat center; a training and conference center; and a chapel. It is from this epicenter that he expects that "the vision" will reach its "appointed time" by the end of 2000.

Measuring Brightness

How does one assess the impact of Bill Bright? Some have dismissed him as being sentimental, pietistic, or simplistic.

Others—including some of his "dear friends"—have denounced him as a "heretic" (his word) for his endorsement of Evangelicals and Catholics Together (a March 1994 statement of mutual recognition between key conservative Catholics and Protestants, aiming at cooperation on a variety of issues) and have challenged him to recant his position, which he refuses to do: "There are tens of millions of true believers among the Catholics who don't believe that salvation is something you can work for. Many are reformers, like Luther."

Others recognize Bright's heralded place in American religious history. Timothy George, dean of Beeson Divinity School, says that Bright is a "major shaper of American theologizing." Mark Noll, professor of Christian thought at Wheaton College, for all his ambivalence about Bright's "tendentious" theology, recognizes that Bright "is one in a long line of faithful activists who have kept alive many of the things that make evangelicalism alive, and which, were it not for them, would otherwise be dead." John Woodbridge of Trinity Evangelical Divinity School numbers him among "the post-World War II entrepreneurial laypeople who felt that the churches were not able to deal effectively with the needs of America's youth" and calls him "one of the most engaging evangelists of the twentieth century."

But, says Noll, "Activists get stuff done—but sometimes by promoting a simpler picture of the world than the world really is," which gets back to the ambivalence factor. To be accessible to the mainstream, the message must be kept simple. To reach the world, it must be "marketable"—easily duplicated, disseminated, and perpetuated (which accounts for the "best and the brightest" strategy, despite Jesus' own ministry to the sick and the lost). It must also work—or the momentum subsides. The mission breaks down.

So there has been a price to pay for the Brights' radical mission. Sometimes women have felt stifled and sidelined in their CCC ministries. Charismatics were once spurned by Crusade. Independent thinkers and "free spirits" won't always catch the CCC stride.

"Billions more are waiting for someone to tell them the most joyful news ever announced, the truth about God."

And Bright's theological "packaging" has sometimes led him into murky waters. His emphasis on "spiritual breathing"—a discipline he contrived that involves exhaling confessed sins and then inhaling cleansing and empowering of the Holy Spirit—has spawned criticism by some who claim he is flirting with works-oriented theology.

But it can be just as quickly said that for every woman who has felt stifled, there are another dozen who have blossomed and flourished under the Crusade mantle (both the Brights promote the full involvement of women in church leadership). And charismatics today are warmly embraced by Bright ("I love their spirit," he says, adding, "They've grown up and we've grown up."). He says spiritual breathing is "the one thing that causes my heart to be constantly aflame for him":

Here I am, Bill Bright, a very sinful, depraved person. Christ comes to live within me, he died on the cross for my sins—past, present, and future. I'm promised that if I walk in the light, the blood of Jesus cleanses me from all sin. Not to live in the joy of the resurrection is to dishonor our Lord, because he gave us the power. It is like pushing your car around instead of driving it.

"There is little doubt that CCC has created a generation of believers who know how to share the basic elements of their faith. He put structure and shoe leather on evangelism at numerous college campuses, which otherwise were almost devoid of a Christian presence," says Darrell Bock, research professor at Dallas Theological Seminary.

"The genius of the movement," says Woodbridge, "is that it didn't fracture into a million pieces when they would go off in their many different directions." Woodbridge attributes this to the uniformity and constant rehearsal of their teachings. "They have been able to expand while keeping the same vision."

That vision is simple: They sow the seed of the gospel across planet Earth. (Bright was a farmer/rancher, after all.) They see their role as "abundant sowers," according to Steve Douglass, leaving the "cost-of-discipleship"-type nurture to the local churches. "We aren't the whole church," says Douglass." We hope it would be perceived as a positive trait that we know what we aren't."

"I'm just Bill Bright," he responds to his critics. "If Christ can change me he can change anyone. I know the joy of living and the power of the Resurrection, not because I'm so good but because he is so wonderful.

"I have one goal in life," he adds. "And that's to take the gospel to everybody on planet Earth. I don't have time for arguments. For 46 years my life has been like a farmer who lifts the calf over the fence."

CCC's critics rightly suggest that the simple, marketable, pragmatic approach to theology does not attend to the problems of thoughtful evangelicals.

"True," says J. I. Packer. "But that is the penalty for being a broad-scale entrepreneur. The Model T couldn't satisfy tastes for sports cars and Cadillacs."

Kelly Hardman cried the first time she used the Four Spiritual Laws. "I didn't want to be perceived the wrong way, but the message was worth risking my reputation."

Seizing the initiative and risking reputations drives the Crusade engine." The average person—98 percent according to our survey—is not sharing hisor her faith," Bright remarks in an interview with the Door (1977). "Why?"

Some would say that depends on what you mean by "sharing" and "faith." But whatever others mean, and whatever methods they employ, the Brights knowwhat they mean when they sow the seed of the gospel. They are telling the world all about it.

Copyright © 1997 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.