“The Liberator has come!” With that declaration, African-American evangelist Tom Skinner concluded his keynote address at Urbana ’70, InterVarsity’s missions conference in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. The gathering of more than 11,000 college students leaped to its feet, exploding in applause and cheers.

Jesus Christ was the “radical” Liberator whom Skinner proclaimed. But for the hundreds of young African-American evangelicals scattered across that assembly hall, Skinner himself was a liberator-their ambassador to the white evangelical church. At last, their struggles and concerns had the chance for a legitimate hearing.

There had been a buzz in the air at Urbana even before Tom Skinner took the stage. College students from all over the U.S. had descended on the campus during the last five days of 1970 to study their Bibles, sing hymns, and hear such speakers as John Stott and Leighton Ford talk about discipleship and world evangelization. But on the second evening of the event, with Skinner at the helm, the student missions conference made a significant departure from its usual program.

In its ninth triennial offering, the Urbana convention had become an influential and highly anticipated occasion, where countless young adults made decisions to enter full-time Christian service. InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (Urbana’s sponsor) was known as one of the evangelical movement’s premier campus ministries. And the Urbana conference was its prime laboratory for mobilization and renewal.

But there had also been controversy surrounding the event. Three years earlier at Urbana ’67, about 60 African-American students, all InterVarsity members, had come to the conference with idealistic notions of finding a connecting point for their black evangelical sentiments. What they found instead was a “white” event, not only in terms of attendance, but also in terms of vision. For the black attendee, there seemed a disregard for the presence and needs of students from non-Anglo cultures.

“I went there bright-eyed and naïve,” remembers Carl Ellis, then a sophomore at the historically black Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia. “But it didn’t take long for me to realize something wasn’t right. I didn’t see anybody from my neighborhood there. I didn’t see anyone talking about missions to the cities or about the concerns of the black population. And I said to myself, ‘I hope these people aren’t deliberately doing this.’ “

Ellis and other African-American students who had the same misgivings tempered their frustration by an unshakable commitment to the biblical ideals of evangelicalism. But if they could not find fellowship and encouragement through organizations such as InterVarsity, where were they to go?

The students gathered for an impromptu prayer meeting that went on for hours. “We weren’t planning on staying up all night,” Ellis continues, “but it was an evening of absolute, fervent prayer that God would raise up an army of African Americans who would be able to minister to our community, our people.”

After Urbana ’67, Carl Ellis and others recruited and campaigned to ensure the next Urbana convention would not be without a notable black presence. Ellis, Hampton Institute’s InterVarsity president, was named to the national advisory committee for Urbana ’70. He convinced InterVarsity that a 28-year-old African-American evangelist by the name of Tom Skinner should be added to the list of plenary speakers. As a result, in 1970, more than 500 black students and Christian leaders flocked to the Urbana convention. The black evangelical renaissance that the students had prayed about three years earlier actually felt within reach.

As the winter of 1970 approached and Skinner officially signed on to speak, there arose a confidence among young black evangelicals across the nation that a new day was imminent: Urbana ’70 was going to be different.

In 1970, Tom Skinner was no stranger to high-profile, ground-breaking positions. Christian radio listeners had heard his weekly teaching program. Thousands had packed venues across the U.S. and in countries as far away as Guyana to hear his streetwise, yet intellectually stimulating preaching. Before his untimely death in 1994, Skinner had influenced a wide audience of both black and white church leaders, theologians, business executives, politicians, social activists, entertainers, and professional athletes.

“Tom was the most visible black evangelical we had at that time who was willing to tell the truth,” says Johnnie Skinner, the late evangelist’s younger brother and a Baptist minister in Knoxville, Tennessee. “It was extremely difficult for any black leader in that type of position to tell the hard truth all the time, but he was trying.”

“Tom Skinner had the clearest understanding of the gospel of anyone that I’ve ever heard, and he was able to articulate that,” adds John Perkins, evangelist and publisher of Urban Family magazine. “He understood the importance of ‘on earth as it is in heaven,’ and that was the heart of his message-living out the kingdom of God. He was a prophet without honor because he was hitting at themes of reconciliation that were too radical for blacks and whites alike.”

A Double Life

Skinner was born a Baptist preacher’s son in the concrete environs of Harlem, New York. A gifted child, he was aware of his intellect at an early age: “By the time I was 14 I could tell you the difference between existentialism and rationalism; between Freudian psychology and behavioristic psychology,” he wrote in his 1968 autobiography, Black and Free.

Although religion was a part of Skinner’s life from the beginning, growing up in inner-city New York gave it little credibility in his estimation. “As a teenager I looked around and I asked my father where God was in all this,” he wrote. “I couldn’t for the life of me see how God, if He cared for humanity at all, could allow the conditions that existed in Harlem.”

Despite his father’s role as a minister, Skinner had come to believe that Christianity was the religion of the American white man. “All the pictures of Christ I saw were the pictures of an Anglo-Saxon, middle-class, Protestant Republican,” he remarked in his Urbana address. “And I said, ‘There is no way that I can relate to that kind of Christ. … He doesn’t look like he could survive in my neighborhood.’ “

During his teen years, Skinner began leading a double life. By day he was president of his high-school student body, a member of the basketball team, president of the Shakespearean Club, and an active member of his church’s youth department. But come nightfall, Skinner could be found among the Harlem Lords, one of New York’s most notorious street gangs. Under Skinner’s leadership, the Lords rioted, looted, robbed, and assaulted other gangs for turf and respect.

He kept up this double existence for several years without his parents’ knowledge. But the young man’s tortured duality came to a head on the eve of what Skinner expected would be the largest and most significant gang fight ever in New York City. “It would have involved five gangs,” Skinner wrote in his book If Christ Is the Answer (1973). “If I were to succeed in leading the fellows to victory … I would emerge as … the most powerful leader in the area.”

But as Skinner prepared for the brawl, God-and a rock-‘n’-roll radio station-interrupted.

At 9 p.m., Skinner expected to hear his favorite deejay’s radio show. However, on this particular night, “an unscheduled program came on and a man began to speak from 2 Corinthians 5:17 … ‘Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old has gone, the new has come!’ ” The man sounded rough and unpolished, the kind of preacher Skinner found distasteful. But Skinner could not stop listening: “He went on to tell me that Jesus Christ was the only person who ever lived who was both the truth about God and the truth about man. … I could never be what God intended me to be without inviting this Christ-who died on the cross because He was capable of forgiving me of my sins, and who rose again from the dead-to live in me. Apart from Him I could never become a new person.”

Years of anger, deceit, and violence had turned the 17-year-old Skinner into a disheartened, conscienceless young man with no regard for the consequences of his actions. But the Word of God, delivered by an uneducated radio preacher, broke through a wall of hatred and disillusionment. Skinner bowed his head and challenged Jesus Christ to turn his life around.

Leaving a street gang was tricky business. Few had voluntarily left the Harlem Lords without losing their lives. So when Skinner went to his 129 fellow gang members to announce he was quitting, he knew he would probably not leave the room alive.

Terrified, Skinner informed the gangbangers that he had accepted Christ into his life and that he could no longer be a member of the Harlem Lords. Not one sound came from the bewildered gang. Skinner turned to leave the room. Still, no response.

To his astonishment, Skinner left the room a free-and unharmed-man. Later, the gang member who had been Skinner’s second-in-command told him that he wanted to kill him that night but that a strange force prevented him. Skinner went on to lead that young man and several other members of the Harlem Lords to faith in Christ. That marked the end of the agnostic gang leader and the beginning of the Harlem evangelist.

Like a street-smart apostle Paul, Skinner immediately began preaching on the streets of Harlem to a ready-made audience of prostitutes, drug dealers, and homeless people. He also ministered to the youth of Harlem, particularly its gang members. He spoke at neighborhood churches and became a respected figure in the community. Soon Skinner teamed with a group of 12 young, influential church and community leaders in Harlem to form the Harlem Evangelistic Association (HEA), an organized effort to reach the inner city with the gospel.

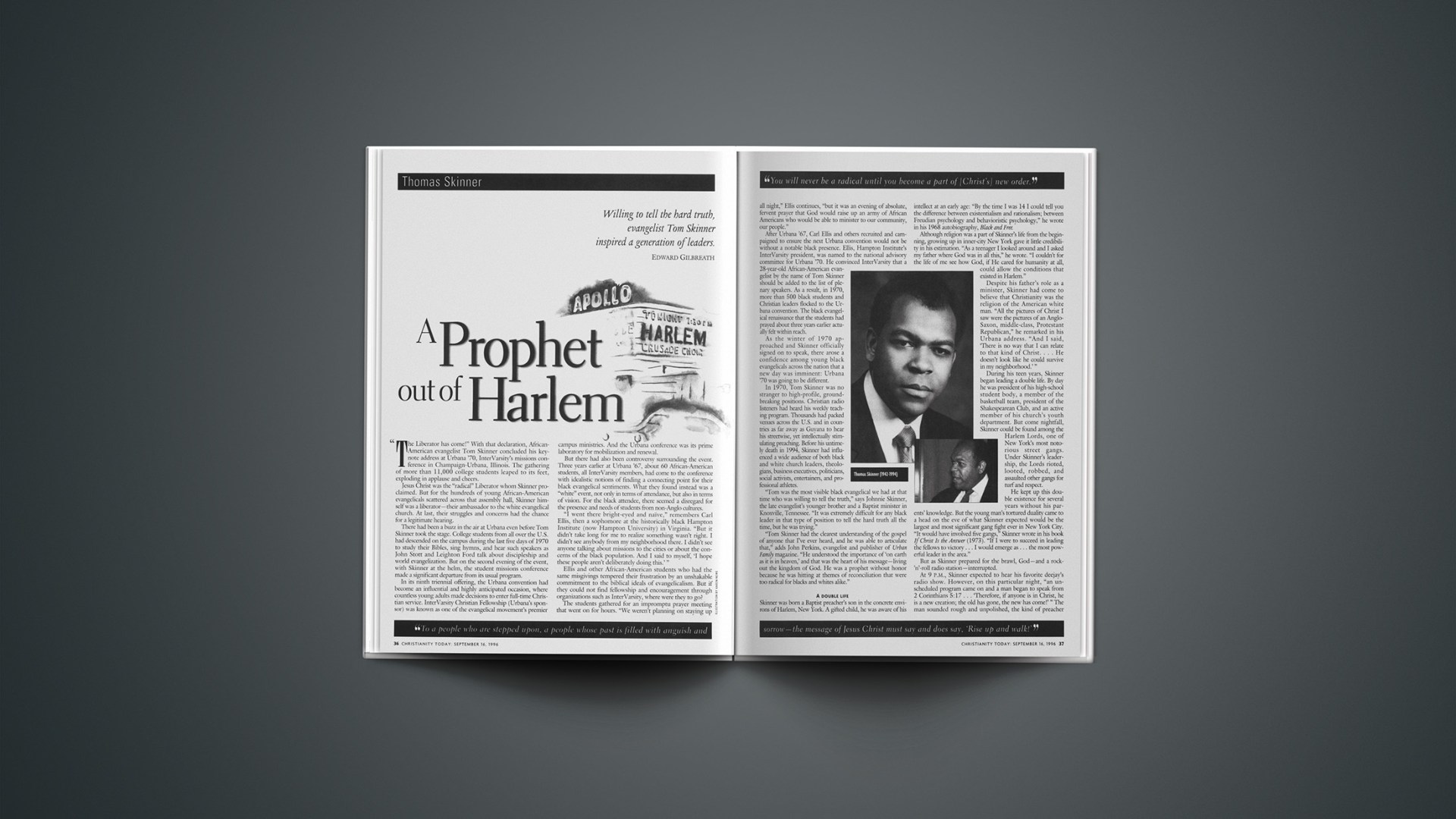

With Skinner named as its chief evangelist, the HEA scheduled its first major crusade for the summer of 1962 at the Apollo Theatre. The group took a crash course in crusade planning and was able to gather the people and resources needed to make the event happen. In the process, however, Skinner began to sense the dilemma of being a young black evangelical in America. When the hea approached white evangelicals in New York whom they knew had experience in crusade development, they were met with “cold shoulders.” Skinner wrote in Black and Free:

I then became aware of how so many white evangelicals are willing to say that the Negro community needs Christ and needs the preaching of the Gospel, but when it comes to action, they are not willing to join forces with brave and uncompromising Negro evangelicals who make the Gospel of Christ relevant in such a community.

But it was not only from the white evangelical community that the hea felt resistance. Blacks were likewise suspicious of this young contingent of black men. Skinner continued:

[We] began to approach Negro evangelical leaders of established reputations in New York City. And again, from many of them, we met polite coldness. They said, “It’s a wonderful thing you’re doing. We’re behind you … we’ll pray for you … but we really can’t get involved.” Minor doctrinal disagreements kept Negro evangelicals from joining together in a cooperative venture such as the one we proposed.

Nevertheless, Skinner and the HEA persevered. During the eight nights of the crusade, thousands of people from both Harlem and the greater New York area gathered to hear Skinner’s messages, breaking attendance records for any single event at the Apollo. Skinner tailored his messages to pique the curiosity of his audience and to address social and economic concerns of African Americans. Those expecting a “black Billy Graham,” as he had been tagged by many, were jolted by Skinner’s unconventional sermons with titles like “The White Man Did It” and “A White Man’s Religion.”

“At several of the rallies I deliberately chose controversial subjects to attract the crowds and challenge them with the claims of Jesus Christ in my own life,” Skinner noted. “I knew the implications, and yet I felt that God was deliberately calling me to go right into the middle of the controversy and make Jesus Christ known.”

By the crusade’s end, more than 2,200 people had responded to Skinner’s presentation of the gospel, and the 20-year-old evangelist was hailed as a preaching phenomenon.

Skinner’s crusade outreach quickly expanded beyond the Harlem community. A radio ministry took Skinner’s phenomenal preaching to listeners throughout the country. Soon, Tom Skinner Crusades was established (which was later changed to Tom Skinner Associates, TSA, when more staff came on board), and the evangelist began speaking on college campuses and at urban arenas throughout the U.S.

Dream Team

William Pannell had a vision for urban ministry within the evangelical church. As the assistant director of leadership training at Youth for Christ (YFC) in the late 1960s, he worked to involve the organization in outreach to his African-American community. He had written an eyebrow-raising book in 1967, titled My Friend the Enemy, which took the white evangelical church to task for what he perceived to be its lack of concern for the holistic gospel message. For many black evangelicals, it was a message to their white counterparts that was long overdue.

Tom Skinner was particularly moved by Pannell’s book and even more so by the man himself. The two men formed an intellectual and spiritual bond. It did not take long for them to find that they shared similar visions for ministry. “As Tom and I talked,” says Pannell, “I realized that perhaps God was telling me that it was time for African Americans to take more responsibility for reaching their communities, and that it would take a black-led organization to make a serious impact.”

In the spring of 1968, Pannell joined Skinner as vice president of TSA. Soon, the ministry assembled a “dream team” lineup of young African-American leaders: Pannell worked to strengthen the crusade outreach and the campus ministry; Henry Greenidge, a musician and minister who had assisted Skinner from the earliest days, settled in as artistic director and leader of TSA’s praise-and-worship band Soul Liberation; and Carl Ellis, briefly courted by InterVarsity, joined Skinner in 1969 as his campus ministry director.

With Pannell on board, TSA began rounding out its evangelistic focus with more prophetic and holistic concerns. According to Pannell, who is now a professor at Fuller Theological Seminary, “It was at the point when we put together the evangelistic and the prophetic traditions that we were led back to the motif of the kingdom of God.” He explains, “Our primary concern was to ascertain what Jesus really meant when he said, ‘The kingdom has come.’ What implications does that have for the church today? What does it look like? How does it affect the way we relate to each other? And how should it change our preaching and our follow-up? Those questions affected everything we did.”

In his 1970 volume entitled How Black Is the Gospel? Skinner highlighted the social demands of Christian theology: “The gospel of Jesus Christ must say to a community that is economically powerless, that is politically powerless, that is socially powerless-to an exploited people, to a people who are stepped upon, a people whose past is filled with anguish and sorrow-the message of Jesus Christ must say and does say, ‘Rise up and walk!’ The church must get involved no matter what the cost; and not only in preaching that message but practicing it.”

Skinner’s influence soon generated interest from audiences far wider than those within the African-American community. In fact, according to Richard Parker, Skinner’s crusade director from 1969 to 1973, “the racial make-up of the attendance was about 60 percent white and 40 percent black.”

Parker, who is now senior pastor of Friendship Community Church in Chattanooga, Tennessee, suspects that Skinner’s unconventional approach put off many blacks. “Whites knew of Tom because he was more or less a product of white evangelicalism in terms of his schooling and thought,” Parker says. “But the black church was for the most part very traditional back then, and the thrust of Tom’s message and the way he conducted himself were rather foreign to the older black church.”

Skinner was no fan of the “traditional” black church and had often been bored and sadly amused by what he saw at his father’s church. “Like so many churches across America, in my church there was no real worship,” he explained in Black and Free. “Sunday morning was a time for the people to gather and be stirred by the emotional clichés. … So long as the service was liberally sprinkled with those time-worn phrases, the people felt good.” Consequently, Skinner made no strong efforts to appeal to those within the traditional black church.

In retrospect, Parker believes TSA was too harsh in its critique of traditional black churches. “I don’t think we courted them in the way we should have,” he says. “There were things that were said that denigrated the black church and alienated some of the black ministers across the country.”

The difference between the “traditional” black church and the “evangelical” black church, observes Oberlin College religion scholar Albert G. Miller, was that the “modern black evangelical movement placed more emphasis on its rationalistic or propositional character and thus highlighted doctrine over the experiential and ecstatic.” These differences were addressed with the founding of the National Negro Evangelical Association in 1963 (later the National Black Evangelical Association). The late William H. Bentley, the organization’s leader, recognizing this divide, suggested that most African-American Christians were, in fact, “evangelical” but were just not aware of such terminology.

Skinner occasionally participated in the meetings of the National Negro Evangelical Association, but his increasingly radical rhetoric, along with his emerging concerns about biblical and racial reconciliation, gradually shifted him away from a place of easy alliances.

Shock Tactics

In 1970, the U.S. Civil Rights Act was six years old; both Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X were dead; and inner-city race riots were a common feature of the nightly news. The nonviolent resistance of the King era had given way to the militancy exemplified by Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panthers. A sense of dashed hopes had seized the civil-rights movement. Despite key advances, American race relations appeared stalled. And, in the estimation of many blacks, they were in fact edging backward.

Not coincidentally, just as Skinner’s ministry was attracting more attention from whites, his outspoken views on issues of social injustice facing the black community intensified (a fact that would lead many Christian radio stations to drop his program due to its “political” content).

In countless speeches and in books such as How Black Is the Gospel? and Words of Revolution (1970), Skinner declared Christ as a radical revolutionary, not unlike Barabbas or, by extension, the Black Power revolutionaries of his own day. No-holds-barred presentations of Scripture marked Skinner’s style. In How Black Is the Gospel? Barabbas is portrayed as a violent Jewish insurrectionist, who, with his band of angry “guerrillas,” hurls Molotov cocktails into the homes of the “honky” Romans in order to usurp the corrupt Roman Empire. And Christ is a revolutionary who agrees with Barabbas about the oppressiveness of the Roman occupation. He wrote: “Jesus would have … said, ‘Barabbas, when you burn the Roman system down, when you have driven the Roman out, … what are you going to replace the system with?’ ” The solution did not lie in the violent overthrow of “the Man,” Skinner said, but rather in a spiritual revolution within men’s minds and hearts.

His freewheeling interpretation was intended to grab his audience’s attention and shock them into a new understanding of Christ. So it was no surprise to Skinner that whites found his assertions harsh and, at times, irreverent. But if the evangelist’s shock tactics were losing him audiences among whites, Skinner’s fan base among African-American students on college campuses was steadily increasing.

Many young black evangelicals, while committed to Christ, had been captivated by the Black Power rhetoric of the late sixties. The Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam constantly challenged black students to abandon any hopes of seeing racial progress within the parameters of white power structures. And the pressure was even greater for young black evangelicals, who were often ridiculed and mocked for adhering to “the white man’s religion.” For them, Tom Skinner’s radical approach to Christianity provided the firepower needed to defend their faith against Black Power assaults.

Ron Potter, a theologian and professor at Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi, first met Skinner while a student at Wheaton College in the late sixties. According to Potter, the group of African Americans at Wheaton during his era represented the first significant black student presence there. In 1969, Potter’s group rallied to have Skinner speak on the Wheaton campus. “Few black evangelicals in the late sixties were able to take on the charismatic evangelists of the secular Black Power movement,” he says. “But Tom was able to help us address the attacks made upon us.”

He adds that Skinner also assisted Wheaton’s African-American students in responding to racial injustices at their school. “We were experiencing a lot of subtle forms of racism at the time, but we could not describe what it was,” Potter recalls. “Tom was able to articulate for us what we had been feeling. He helped us to differentiate between biblical Christianity and the Christ of the white evangelical culture.”

Kay Coles James, dean of government at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and a noted evangelical speaker, was a student at Hampton Institute in the late sixties when Skinner made several visits to that campus. “We were trying to figure out what it meant to be black and Christian in the culture of that day, and we realized we were not going to find all the answers through groups like InterVarsity,” she says. “What we found in Tom Skinner was a towering figure of a man, straight off the streets of Harlem, who had a real connection with our unique needs. He gave us hope and empowered us as Christ’s ambassadors to those blacks on our campus who were skeptical toward Christianity.”

And, to the delight of Potter, James, and hundreds of other young black evangelicals across the nation, this was the Tom Skinner who arrived at the Urbana ’70 missions conference ready to stir 11,000 students to a higher understanding of the gospel message.

Radical Departures

Soul Liberation didn’t look like any other music group that had performed on the Urbana stage. Their afros, multi-colored attire, and Afro-centric symbols made them seem more like a sanctified Sly and the Family Stone than an evangelical praise-and-worship ensemble. And the predominantly white Urbana crowd was not altogether prepared for their style of ministry. The group regularly accompanied Skinner to college campuses and evangelistic rallies, but as the group took the stage to do a song prior to Skinner’s keynote address, the band members knew they would be journeying through uncharted territory.

After a day and a half of singing familiar hymns and choruses, the Urbana crowd was off guard when Soul Liberation started playing the group’s gospel anthem, “Power to the People,” whose lyrics borrowed heavily from Black Power idioms. “It was such a radical departure and so different that people gasped when we began,” says Henry Greenidge, the group’s leader. “Our clothes, the drums, the bass; it was too much for them.”

After initial shock, however, the audience soon jumped to its feet to sing along as it realized the Christo-centric focus of Soul Liberation’s song. For the white students, it was an instant lesson in contemporary black culture.

Greenidge, who is now senior pastor of Irvington Covenant Church in Portland, Oregon, remembers that second night of Urbana ’70 as being “very electric.” “It felt like something historic was happening,” he says. “Tom was our spokesperson, and we knew as soon as we finished he would be giving a major address. I think Tom’s speech and our music had a hand-in-glove effect.”

When Tom Skinner finally stepped to the podium, the crowd was already charged for what they anticipated would be a revolutionary address. The majority of the black students sat together in front of the platform, awaiting sage words from the man who, for at least that evening, would be their Moses.

Skinner began his Urbana address, officially titled “The U.S. Racial Crisis and World Evangelism,” with a friendly, humorous warm-up that offered a brief history lesson on the plight of the “Negro” in America. Drawing from secular and biblical sources, the young evangelist dramatically uncovered the sad state of race relations in the U.S. and the American church’s utter failure to address the problem. One by one, Skinner picked apart the issues that held evangelicalism captive to white prejudice and indifference.

On U.S. nationalism: “As a black Christian I have to renounce Americanism. I have to renounce any attempt to wed Jesus Christ off to the American system. I disassociate myself from any argument that says a vote for America is a vote for God. I disassociate myself from any argument which says God sends troops to Asia, that God is a capitalist, that God is a militarist, that God is the worker behind our system.”

On white fears of miscegenation: “I don’t know where white people get the idea that they are so utterly attractive that black people are just dying to marry them.”

On white evangelicals who ignored the plight of the inner city: “If you … told him about the social ills of Harlem, he would say, ‘Christ is the answer!’ Yes, Christ is the answer. But Christ has always been the answer through somebody. It has always been the will of God to saturate the common clay of man’s humanity and then send that man in open display to a hostile world as a living testimony that it is possible for the invisible God to make himself visible in a man.”

After some 20 minutes of provocative preaching, Skinner “brought it home” with a proclamation of a “revolutionary” Savior who had come to “infiltrate” and “overthrow” the existing world order to establish his Father’s kingdom.

At the end, Skinner’s voice scraping its upper registers, he reached for one last elocutionary blitz: “You will never be a radical,” he declared to the students, “until you become a part of [Christ’s] new order, and then go into a world that is enslaved; a world that is filled with hunger and poverty and racism and all those things that are the work of the devil. Proclaim liberation to the captives … go into the world and tell men who are bound mentally, spiritually, and physically, ‘The Liberator has come!’ “

A thunderous and seemingly endless standing ovation, from black and white alike, shook the University of Illinois assembly hall.

“It was incredible,” remembers Ron Potter. “It was like heaven on earth.”

“Tom was absolutely prophetic that night,” says Carl Ellis, now president of Project Joseph, a church renewal ministry in Chattanooga, Tennessee. “I knew several people who were there who just didn’t give a hoot about Christianity, but they were shaken to their foundations that night.”

“That speech was a pinnacle of visionary and prophetic expression,” remarks Albert Miller. “It gave both African Americans and whites a vision of what being a black evangelical Christian could be. That they could actually impact not only a community, but a world.”

But for Pete Hammond, a white InterVarsity leader who helped plan Urbana ’70 to include more African Americans, Skinner’s speech brought ambiguous feelings. “For me, it was a mixture of fear and joy,” he says. “I was fearful that we were going to polarize white evangelicals who had never engaged the subject of race so directly. But I was joyful over seeing young black leaders together in a national position to worship, to celebrate, and to find affirmation and a platform to bring their brilliance to the church.”

William Pannell remembers sitting behind Skinner on the platform as he delivered his address. “It was the most powerful moment that I’ve ever experienced at the conclusion of a sermon,” he says. “For perhaps the first time in the history of the Urbana conferences, not only was a black evangelical a keynote speaker, but he was able to cast the Christian mission in the context of a world that was falling apart. Tom was not just talking about going into the world to evangelize, he was talking about linking hands with the Savior who came to take over.”

Troubled Times

Following Urbana ’70, Tom Skinner and TSA continued to be a force among evangelicals. But as his public success continued, cracks began to show in Skinner’s private life. By 1971, Skinner’s demanding ministry schedule had taken its toll on his marriage to Vivian Sutton, Skinner’s childhood sweetheart and a former crusade musician. Tom and Vivian had been married since 1963 and had two daughters, Lauren and Kyla. Although the couple initially demonstrated all the signs of a happy family, the rigors of a high-profile ministry proved too much for Skinner to balance with his family life. Separation, and ultimately a divorce, followed when Skinner failed to make the changes necessary to restore his marriage.

While many of his ministry associates were aware of the evangelist’s marital woes, Skinner at first kept the critical condition of his marriage hidden from even his closest friends. “The TSA board knew that the marriage was stormy, but not because Tom had told us,” explains Pannell. “We knew because we were the ones Vivian would call wondering where her husband was.”

“Since I was not as involved in his ministry, I think I was probably more sensitive to the problems,” says Skinner’s ex-wife, Vivian Bartee. “Tom received a lot of fame and prestige at a very young age, and I believe that made it easy for him to turn a deaf ear to a spouse who was telling him that things were not right in his own household. I think he was embarrassed to admit that there was a problem.”

Skinner’s oldest daughter, Lauren Gaines, now 32, remembers spending much time traveling with her dad, especially in the early part of Skinner’s ministry. But with the birth of her younger sister in 1970 and Skinner’s rapidly growing prominence, Lauren soon found herself seeing less and less of her father.

“I remember being about nine years old and being very frustrated about how much he was gone,” she recalls. “But the Lord ministered to me through another child my age who sent me a card and a wooden cross she had made. She sent it to tell me thanks for letting my dad come to where she lived, because she had gotten to know Jesus through my father’s ministry. At that point, when I was probably struggling the most with my father’s absence, I got ministered to by another child my age. And I realized just how important Dad’s work was.”

Despite Skinner’s absences, Gaines insists he never stopped being a good father. “He impressed upon Kyla and me the importance of a relationship with Christ and the necessity of receiving a good education,” says Gaines, who today works with World Impact Ministries in Newark, New Jersey.

For Bartee, now a school teacher in Brooklyn, New York, it is not as easy to overcome Skinner’s shortcomings as a husband and father. “By God’s grace, I was able to forgive Tom,” says Bartee, “and God even ministered to me through Tom’s ministry. But we were never truly friends again.”

As word of Skinner’s marital problems spread, the evangelist saw many other friendships come to an end as well. And, consequently, tsa saw its support from the wider evangelical community dwindle.

“The divorce became the official occasion for white evangelicals to divorce Tom,” contends Potter. “He had long ago become a persona non grata for many white evangelicals who were offended by his critique of white Christianity, but now they had an official reason to desert him.”

At the same time, Skinner had slowly moved away from the team-ministry concept that had originally driven TSA, says Pannell. With more solo ministry opportunities presenting themselves, such as his role as chaplain of the Washington Redskins football team, Skinner became less and less of a team player. “It was a very sensitive area for many of us on the TSA board,” admits Pannell.

And so, with the lingering stigma of Skinner’s failed marriage and an ever-growing wedge between the evangelist and his once close-knit ministry associates, TSA began to unravel.

By 1975, the bottom had fallen out of Skinner’s organization. Coworkers such as Pannell, Ellis, and Greenidge gradually left the organization. And Stan Long, now a pastor and consultant to the American Tract Society, was brought aboard in the hope of salvaging the ailing ministry. But the golden age of Tom Skinner Associates had passed, and Skinner, his ministry a shadow of what it had once been, entered a long period of reevaluation.

New Horizons

The 1980s signaled a new era for Skinner. Having survived several years of rejection and bouts of depression, Skinner’s ministry turned away from an evangelistic emphasis and focused more on Christian leadership training. In addition, Skinner’s ongoing work as chaplain of the Washington Redskins expanded his influence in mainstream celebrity circles.

Most significantly, in 1981, Skinner married Barbara Williams, an attorney and secretary for the Congressional Black Caucus in Washington, D.C. With marriage to Barbara came new happiness, and through her connections his ministry began making inroads into the black political elite and traditional black church leadership whom Skinner had once scorned. Powerful figures in the black community such as Jesse Jackson and the late minister Samuel Hines of the Third Street Church of God in Washington, D.C., became his close confidants.

Many friends, like Ellis, believe some of Skinner’s greatest contributions came during this latter phase of his life. “By the time of his death, Tom had had an enormous influence on countless black leaders,” says Ellis. “He had integrated his theology and social activism in such a way that you could clearly see he was making a profound contribution.”

But even reaching a more mainstream audience, Skinner’s central motif of the “kingdom of God” never shifted. “The stories might have changed, but his main theme remained the same,” says Barbara Skinner, who now directs the Skinner Farm Leadership Institute in Tracy’s Landing, Maryland. “He was constantly looking for that body of believers who were the life expression of God’s kingdom.”

Patrick Morley, a white Orlando, Florida, business executive, was deeply affected by Skinner in the latter half of the evangelist’s life. After Skinner delivered seminars to Morley’s company, the two became fast friends. “Tom poured hundreds of hours into discipling me around our dinner table, after tennis, or in a car going somewhere,” Morley told Urban Family. “He never would give up on anyone; [he saw] the potential in everyone, even when others would write you off.”

Skinner and Morley joined together in 1993 to launch Mission Mississippi, a racial-reconciliation ministry based in Jackson. The pair also traveled to Israel together in January 1994, just four months before Skinner’s death. “Tom made some blacks and some whites angry,” says Morley, “but he deeply influenced an entire generation of people to think more deeply about their lives.”

Skinner’s death from leukemia at age 52 was a shock to many. At his funeral, an unusual gallery of individuals from all segments of American society came to pay their respects. The diverse lineup included Jesse Jackson, poet Maya Angelou, Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Shabazz, and Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan-not to mention the countless others with whom Skinner had worked in the heyday of TSA.

“He was a true reconciler,” says Johnnie Skinner about his brother. “Even in his death, he was bringing different people together.”

Today, nearly 26 years after Skinner’s landmark speech at Urbana ’70, there is also a fresh sense of hope and purpose among those young black evangelicals who were inspired by Skinner’s memorable words.

“The real meaning of it is becoming increasingly apparent to me as I continually encounter men and women who have made the choice for ministry in part because of what happened there,” observes Greenidge. “Back then, we wanted to see white evangelicalism make some wholesale changes, but it wasn’t happening. However, out of that movement came people like Tony Evans, Matthew Parker, and many other black leaders who are making a huge impact in today’s church.”

An extended list of those directly or indirectly influenced by Skinner’s ministry reads like a virtual who’s who of what has been called the “new black evangelicalism”: Carl Ellis, Kay Coles James, Crawford Loritts (of Campus Crusade for Christ), Albert Miller, Spencer Perkins (of Urban Family), Ron Potter, and Brenda Salter McNeil (of InterVarsity), to name a few.

Some, like Miller and Potter, have expressed minor disappointment that the full potential of Skinner’s vision was not realized by the evangelist during TSA’s shining years. Contends Potter: “Tom knew how to fire up young blacks, but there was an inability on the part of TSA to flesh out the message. After the Urbana ’70 speech, many of us were looking for leadership on what to do next, but it never happened.”

Still, he says, the finger must point back to those young black evangelicals who were imparted a new vision by a streetwise prophet from Harlem.

“When Tom died, an era came to an end,” Potter concludes. “But that means those of us who have been mentored by Tom now have a responsibility to carry on that vision. We sometimes complain that ‘the Liberator is late.’ Well, he may be late because he’s waiting on us.”

Edward Gilbreath is associate editor of New Man magazine.

Copyright © 1996 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.