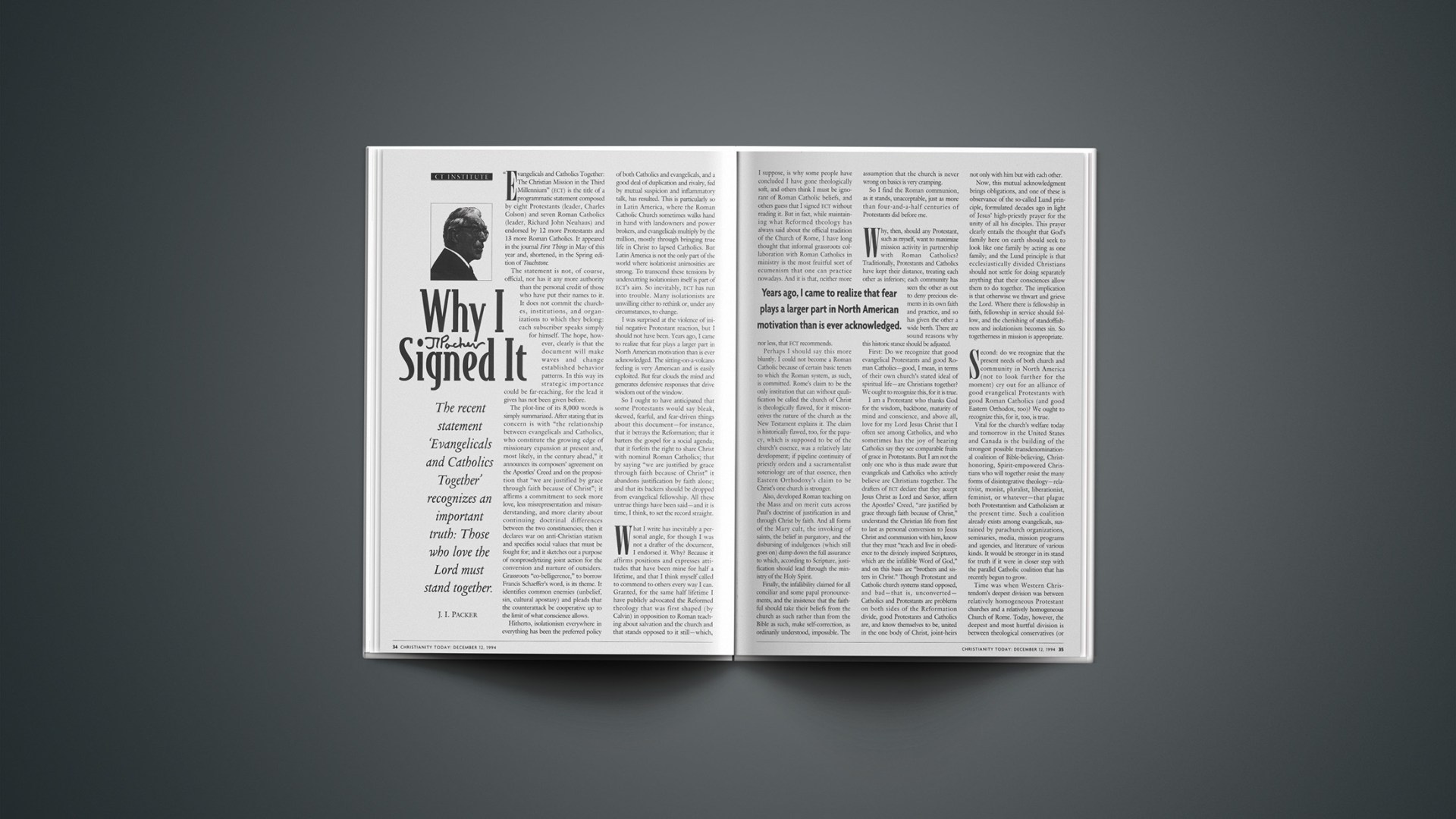

"Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium" (ECT) is the title of a programmatic statement composed by eight Protestants (leader, Charles Colson) and seven Roman Catholics (leader, Richard John Neuhaus) and endorsed by 12 more Protestants and 13 more Roman Catholics. It appeared in the journal First Things in May of this year and, shortened, in the Spring edition of Touchstone.

The statement is not, of course, official, nor has it any more authority than the personal credit of those who have put their names to it. It does not commit the churches, institutions, and organizations to which they belong: each subscriber speaks simply for himself. The hope, however, clearly is that the document will make waves and change established behavior patterns. In this way its strategic importance could be far-reaching, for the lead it gives has not been given before.

The plot-line of its 8,000 words is simply summarized. After stating that its concern is with "the relationship between evangelicals and Catholics, who constitute the growing edge of missionary expansion at present and, most likely, in the century ahead," it announces its composers' agreement on the Apostles' Creed and on the proposition that "we are justified by grace through faith because of Christ"; it affirms a commitment to seek more love, less misrepresentation and misunderstanding, and more clarity about continuing doctrinal differences between the two constituencies; then it declares war on anti-Christian statism and specifies social values that must be fought for; and it sketches out a purpose of nonproselytizing joint action for the conversion and nurture of outsiders. Grassroots "co-belligerence," to borrow Francis Schaeffer's word, is its theme. It identifies common enemies (unbelief, sin, cultural apostasy) and pleads that the counterattack be cooperative up to the limit of what conscience allows.

Hitherto, isolationism everywhere in everything has been the preferred policy of both Catholics and evangelicals, and a good deal of duplication and rivalry, fed by mutual suspicion and inflammatory talk, has resulted. This is particularly so in Latin America, where the Roman Catholic Church sometimes walks hand in hand with landowners and power brokers, and evangelicals multiply by the million, mostly through bringing true life in Christ to lapsed Catholics. But Latin America is not the only part of the world where isolationist animosities are strong. To transcend these tensions by undercutting isolationism itself is part of ECT's aim. So inevitably, ECT has run into trouble. Many isolationists are unwilling either to rethink or, under any circumstances, to change.

I was surprised at the violence of initial negative Protestant reaction, but I should not have been. Years ago, I came to realize that fear plays a larger part in North American motivation than is ever acknowledged. The sitting-on-a-volcano feeling is very American and is easily exploited. But fear clouds the mind and generates defensive responses that drive wisdom out of the window.

So I ought to have anticipated that some Protestants would say bleak, skewed, fearful, and fear-driven things about this document – for instance, that it betrays the Reformation; that it barters the gospel for a social agenda; that it forfeits the right to share Christ with nominal Roman Catholics; that by saying "we are justified by grace through faith because of Christ" it abandons justification by faith alone; and that its backers should be dropped from evangelical fellowship. All these untrue things have been said – and it is time, I think, to set the record straight.

What I write has inevitably a personal angle, for though I was not a drafter of the document, I endorsed it. Why? Because it affirms positions and expresses attitudes that have been mine for half a lifetime, and that I think myself called to commend to others every way I can. Granted, for the same half lifetime I have publicly advocated the Reformed theology that was first shaped (by Calvin) in opposition to Roman teaching about salvation and the church and that stands opposed to it still – which, I suppose, is why some people have concluded I have gone theologically soft, and others think I must be ignorant of Roman Catholic beliefs, and others guess that I signed ECT without reading it. But in fact, while maintaining what Reformed theology has always said about the official tradition of the Church of Rome, I have long thought that informal grassroots collaboration with Roman Catholics in ministry is the most fruitful sort of ecumenism that one can practice nowadays. And it is that, neither more nor less, that ECT recommends.

Perhaps I should say this more bluntly. I could not become a Roman Catholic because of certain basic tenets to which the Roman system, as such, is committed. Rome's claim to be the only institution that can without qualification be called the church of Christ is theologically flawed, for it misconceives the nature of the church as the New Testament explains it. The claim is historically flawed, too, for the papacy, which is supposed to be of the church's essence, was a relatively late development; if pipeline continuity of priestly orders and a sacramentalist soteriology are of that essence, then Eastern Orthodoxy's claim to be Christ's one church is stronger.

Also, developed Roman teaching on the Mass and on merit cuts across Paul's doctrine of justification in and through Christ by faith. And all forms of the Mary cult, the invoking of saints, the belief in purgatory, and the disbursing of indulgences (which still goes on) damp down the full assurance to which, according to Scripture, justification should lead through the ministry of the Holy Spirit.

Finally, the infallibility claimed for all conciliar and some papal pronouncements, and the insistence that the faithful should take their beliefs from the church as such rather than from the Bible as such, make self-correction, as ordinarily understood, impossible. The assumption that the church is never wrong on basics is very cramping.

So I find the Roman communion, as it stands, unacceptable, just as more than four-and-a-half centuries of Protestants did before me.

Why, then, should any Protestant, such as myself, want to maximize mission activity in partnership with Roman Catholics? Traditionally, Protestants and Catholics have kept their distance, treating each other as inferiors; each community has seen the other as out to deny precious elements in its own faith and practice, and so has given the other a wide berth. There are sound reasons why this historic stance should be adjusted.

First: Do we recognize that good evangelical Protestants and good Roman Catholics – good, I mean, in terms of their own church's stated ideal of spiritual life – are Christians together? We ought to recognize this, for it is true.

I am a Protestant who thanks God for the wisdom, backbone, maturity of mind and conscience, and above all, love for my Lord Jesus Christ that I often see among Catholics, and who sometimes has the joy of hearing Catholics say they see comparable fruits of grace in Protestants. But I am not the only one who is thus made aware that evangelicals and Catholics who actively believe are Christians together. The drafters of ECT declare that they accept Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, affirm the Apostles' Creed, "are justified by grace through faith because of Christ," understand the Christian life from first to last as personal conversion to Jesus Christ and communion with him, know that they must "teach and live in obedience to the divinely inspired Scriptures, which are the infallible Word of God," and on this basis are "brothers and sisters in Christ." Though Protestant and Catholic church systems stand opposed, and bad – that is, unconverted – Catholics and Protestants are problems on both sides of the Reformation divide, good Protestants and Catholics are, and know themselves to be, united in the one body of Christ, joint-heirs not only with him but with each other.

Now, this mutual acknowledgment brings obligations, and one of these is observance of the so-called Lund principle, formulated decades ago in light of Jesus' high-priestly prayer for the unity of all his disciples. This prayer clearly entails the thought that God's family here on earth should seek to look like one family by acting as one family; and the Lund principle is that ecclesiastically divided Christians should not settle for doing separately anything that their consciences allow them to do together. The implication is that otherwise we thwart and grieve the Lord. Where there is fellowship in faith, fellowship in service should follow, and the cherishing of standoffishness and isolationism becomes sin. So togetherness in mission is appropriate.

Second: do we recognize that the present needs of both church and community in North America (not to look further for the moment) cry out for an alliance of good evangelical Protestants with good Roman Catholics (and good Eastern Orthodox, too)? We ought to recognize this, for it, too, is true.

Vital for the church's welfare today and tomorrow in the United States and Canada is the building of the strongest possible transdenominational coalition of Bible-believing, Christ-honoring, Spirit-empowered Christians who will together resist the many forms of disintegrative theology – relativist, monist, pluralist, liberationist, feminist, or whatever – that plague both Protestantism and Catholicism at the present time. Such a coalition already exists among evangelicals, sustained by parachurch organizations, seminaries, media, mission programs and agencies, and literature of various kinds. It would be stronger in its stand for truth if it were in closer step with the parallel Catholic coalition that has recently begun to grow.

Time was when Western Christendom's deepest division was between relatively homogeneous Protestant churches and a relatively homogeneous Church of Rome. Today, however, the deepest and most hurtful division is between theological conservatives (or "conservationists," as I prefer to call them), who honor the Christ of the Bible and of the historic creeds and confessions, and theological liberals and radicals who for whatever reason do not; and this division splits the older Protestant bodies and the Roman communion internally. Convictional renewal within the churches can only come, under God, through sustained exposition, affirmation, and debate, and since it is substantially the same battle that has to be fought across the board, a coalition of evangelical and Catholic resources for the purpose would surely make sense.

It is similarly vital for the health of society in the United States and Canada that adherents to the key truths of classical Christianity – a self-defining triune God who is both Creator and Redeemer; this God's regenerating and sanctifying grace; the sanctity of life here, the certainty of personal judgment hereafter, and the return of Jesus Christ to end history – should link up for the vast and pressing task of re-educating our secularized communities on these matters. North American culture generally has lost its former knowledge of what it means to revere God, and hence it has lost its values and standards, its shared purposes, its focused hopes, and, in a word, its knowledge of what makes human life human, so that now it drifts blindly along materialistic, hedonistic, and nihilistic channels. Again, it is the theological conservationists, and they alone – mainly, Roman Catholics and the more established evangelicals – who have resources for the rebuilding of these ruins, and their domestic differences about salvation and the church should not hinder them from joint action in seeking to re-Christianize the North American milieu.

In its section titled "We Contend Together," ECT spells out a resolve to uphold religious freedom, sanctity of life, family values, parental choice in education, moral standards in society, and democratic institutions worldwide. This should be as much an agenda for all evangelicals as it is for any Catholic, and these contendings are crucial at present; but they will only gain credibility if the view of reality in which they are rooted takes hold of people's minds. Propagating the basic faith, then, remains the crucial task, and it is natural to think it will best be done as a combined operation. So togetherness in witness is timely.

Third: do we recognize that in our time mission ventures that involve evangelicals and Catholics side by side, not only in social witness but in evangelism and nurture as well, have already emerged? We ought to recognize this, for it is a fact.

From the many available examples, I take three. Among them, they illustrate the point sufficiently. The late Francis Schaeffer focused the concept of co-belligerence, that is, joint action for agreed objectives by people who disagree on other things, and then implemented it by leading evangelicals into battle alongside Roman Catholics on the abortion front, where – thank God! – they remain. Billy Graham's cooperative evangelism, in which all the churches in an area, of whatever stripe, are invited to share, is well established on today's Christian scene. And so are charismatic get-togethers, some of them one-off, some of them regular, and some of them huge, where the distinction between Protestant and Catholic vanishes in a Christ-centered unity of experience. So the togetherness that ECT pleads for has already begun.

ECT, then, must be viewed as fuel for a fire that is already alight. The grassroots coalition at which the document aims is already growing. It can be argued that, so far from running ahead of God, as some fear, ECT is playing catch-up to the Holy Spirit, formulating at the level of principle a commitment into which many have already entered at the level of practice; and certainly, the burden of proof must rest on any who wish to deny that this is so.

I conclude, then, on grounds of biblical principle, reinforced by current pressures and precedents, that ECT's modeling of an evangelical-Roman Catholic commitment to partnership in mission within set limits and without convictional compromise is essentially right, and I remain glad to endorse it. In the days when Rome seemed to aim at political control of all Christendom and the death of Protestant churches, such partnership was not possible. But those days are past and after Vatican II can hardly return. Whatever God's future may be for the official Roman Catholic system, present evangelical partnership with spiritually alive Roman Catholics in communicating Christ to unbelievers and upholding Christian order in a post-Christian world needs to grow everywhere, as ECT maintains. This should be beyond question.

Concerning ECT itself, however, questions remain, and it is time to turn to them. Whether it was wisest to write this document in a flowing, rhetorical, open-textured way, so that it reads like a political speech; whether it would have helped to have professional evangelical theologians involved in the drafting process (there were none); and whether any particular rearrangements, additions, and tightenings up would make ECT more persuasive to its suspicious critics – all are questions we may leave on one side. ECT's tone and thrust are right, and anyone who has learned not to rip phrases out of their context will see well enough what is intended.

Some, however, denounce ECT as a sellout of evangelical Protestantism and conclude that the evangelical team was incompetent, irresponsible, and outmaneuvered. The difficulties these critics feel raise issues of importance.

First: Does it not always put you in a false position to work with people with whom you do not totally agree? Not if you agree on the specific truths and goals the proposed collaboration involves, and if the points of nonagreement and therefore the limits of togetherness in action are well understood. Here, I judge, ECT, fairly read, passes muster.

Second: May ECT realistically claim, as in effect it does, that its evangelical and Catholic drafters agree on the gospel of salvation? Yes and no. If you mean, could they all be relied on to attach the same small print to their statement, "we are justified by grace through faith because of Christ," no. (The Tridentine assertion of merit and the Reformational assertion of imputed righteousness can hardly be harmonized.) If you mean, do all present-day Catholics focus on the living Christ, Lord, Savior, and coming King as the direct object of the sinner's faith and hope in the way ECT does, doubtless no again. (I imagine some traditional Catholics have problems with ECT at this point, though today's Catholic theologians observably do not.) But if you mean, does ECT's insistence that the Christ of Scripture, creeds, and confessions is faith's proper focus, and that "Christian witness is of necessity aimed at conversion," not only as an initial step but as a personal life-process, and that this constitutes a sufficient account of the gospel of salvation for shared evangelistic ministry, then surely yes. What brings salvation, after all, is not any theory about faith in Christ, justification, and the church, but faith itself in Christ himself. Here also ECT, fairly read, seems to me to pass muster, though the historic disagreements at theory level urgently now need review.

Third: Does not ECT treat baptismal regeneration, which Catholics affirm and evangelicals deny, as acceptable doctrine? No. Its logic (smudged somewhat by loose drafting, but clear enough to fair readers) is that agreement on the necessity of personal conversion makes evangelistic cooperation viable, in principle and in practice, despite this continuing disagreement. ECT clearly envisages an evangelism that, by requiring transactional trust in the living Christ, rules out all thought of baptism without faith saving anyone.

Fourth: Does not ECT imply that Protestants should stop trying to evangelize Roman Catholics, or make Protestants out of them? No. ECT walks a tightrope here, as follows: "We condemn the practice of recruiting people from another community for purposes of denominational or institutional aggrandizement. … It is neither theologically legitimate nor a prudent use of resources for one Christian community to proselytize among active adherents of another Christian community. … Those converted … must be given full freedom and respect as they discern and decide the community in which they will live their new life in Christ."

It is clear that sharing Christ with inactive, nominal, lifeless-looking adherents of any communion is permitted by this wording; so is explaining the pros and cons of choosing a church, and the importance, for growth, of being under faithful ministry of the word. What is ruled out is associating salvation or spiritual health with churchly identity, as if a Roman Catholic cannot be saved without becoming a Protestant or vice versa, and on this basis putting people under pressure to change churches.

The flow of thought in the above extract shows that "theologically legitimate" means "theologically appropriate." This is not the only example of loose phrasing in ECT. But all comes clear if one follows the flow of ideas.

So I find that ECT is not at all a sellout of Protestantism, but is in fact a well-judged, timely call to a mode of grassroots action that is significant for furthering the kingdom of God.

To be sure, ECT is only a beginning. Those for whom anti-Romanism or anti-Protestantism is part of their identity and ministry will need more than ECT to alter their mindset, as will those Protestants who deny that Roman Catholics can be Christians without leaving Rome. There needs now to be a rigorous review of how the theological questions that have thus far divided the Catholic and Protestant churches look in light of the new ECT commitment. Well does ECT say, "The differences and disagreements … must be addressed more fully and candidly in order to strengthen between us a relation of trust in obedience to truth." Without this ECT will get nowhere, nor will it deserve to.

To help shape this proposed study of the historic disagreements, Michael Horton and I put together some agenda suggestions that are printed in Modern Reformation (July-August 1994). What is important, however, is not that the work be done our way, but that the work be done as distinct from not done; for such study is the necessary next step.

But ECT is a good beginning, and for it I continue to thank God.

J. I. Packer is Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Systematic Theology at Regent College, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.