An American who lived in Washington State once hosted an old college buddy from Alabama for a summer vacation. As the visitor’s week drew to a close, the Washingtonian invited him to come out the back door. You’ve been here all this time,” he said, “and I haven’t told you that our yard ends at the Canada/U.S.border. Why don’t we walk through the hedge so that you can say you’ve been to Canada?”

His friend liked that idea. But,” he replied, “shouldn’t I bring a jacket?”

Americans assume that Canada is just like the United States—except colder. When it comes to evangelicals in Canada, the stereotype may be partly true: Canadian evangelicals live and witness in a chillier cultural climate. While Christianity in the nineteenth century transformed Canada even more dramatically than America, decades of secularization have profoundly cooled the nation’s once-Christian atmosphere. And even though recent polls show a slight upturn in church attendance after decades of precipitous declines the picture is still not bright. How have Canada’s evangelicals responded? As the clustering of evangelical churches and ministries known as the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada celebrates its thirtieth anniversary, evangelicals in the States stand to learn much from their Canadian cousins.

AN AMERICAN IN TORONTO

At first glance, Canadian evangelicalism may not seem especially distinct from the American variety. A recent Christian conference in southern Ontario, for example, boasted a lineup of American standbys: John Wimber, Jim Wallis, and Ken Medema. Still other Americans filled out the ranks and—oh, yes—two Canadians were featured as well: Don Posterski, a widely known writer on church life and social trends in Canada, and David Mainse, host of Canada’s most popular Christian talk show, 100 Huntly Street.

Another Canadian evangelical talk show recently advertised its most attractive guests: Each was a prominent American evangelical. Walk into any evangelical bookstore and you find the same American authors prominently on display. As you browse, try to locate Canadian authors or publishers—while you listen to Amy Grant, Carman, or some other American musician over the sound system.

Americans may predominate in Canada’s popular evangelical culture, but some British influence remains. John Stott, J. I. Packer (now a Canadian himself), Alister McGrath, and the late David Watson continue to be widely read. And on Sunday morning, many congregations will sing “Shine, Jesus, Shine” or some other praise song by English composer Graham Kendrick.

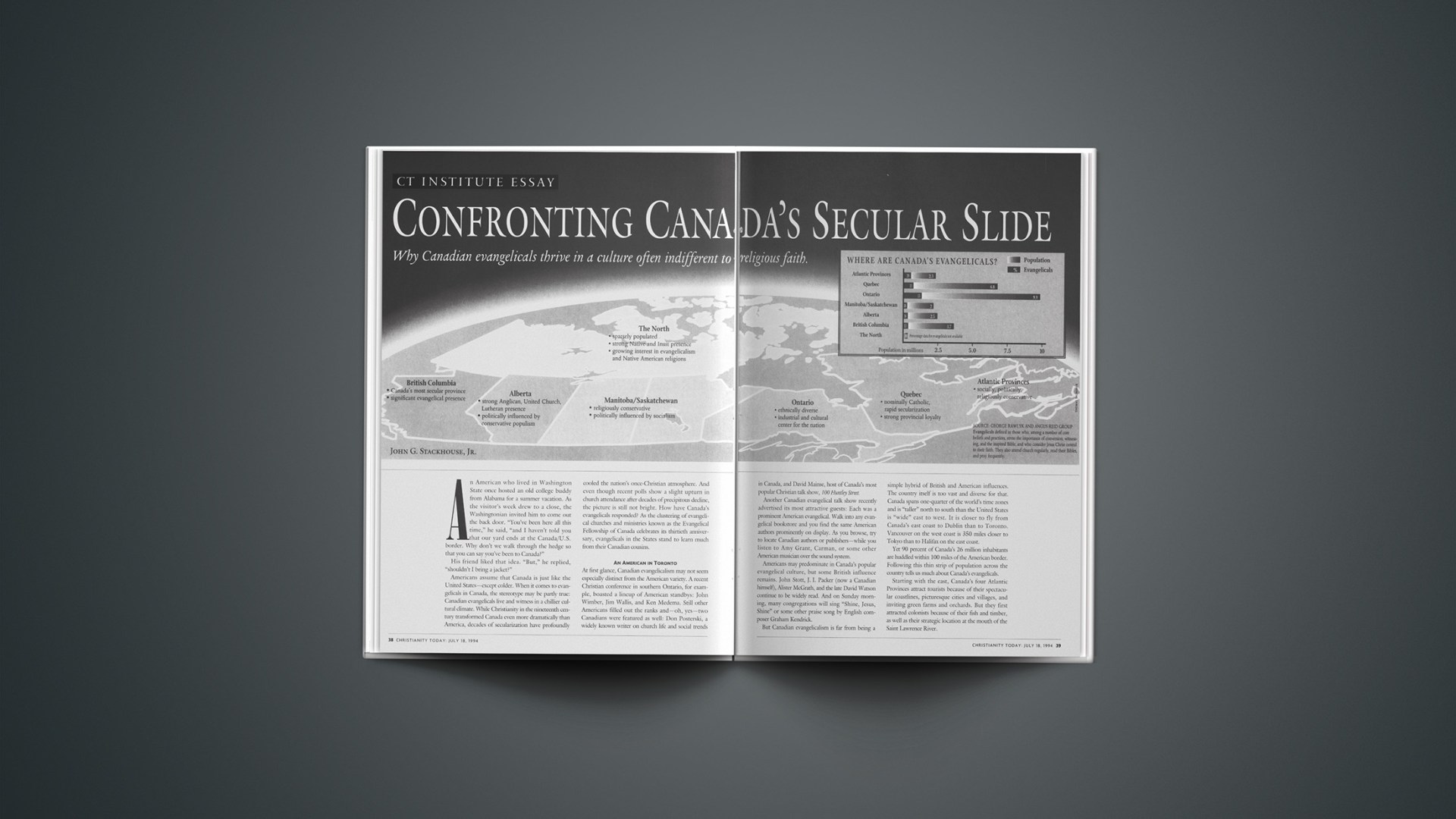

But Canadian evangelicalism is far from being a simple hybrid of British and American influences. The country itself is too vast and diverse for that. Canada spans one-quarter of the world’s time zones and is “taller” north to south than the United States is “wide” east to west. It is closer to fly from Canada’s east coast to Dublin than to Toronto. Vancouver on the west coast is 350 miles closer to Tokyo than to Halifax on the east coast.

Yet 90 percent of Canada’s 26 million inhabitants are huddled within 100 miles of the American border. Following this thin strip of population across the country tells us much about Canada’s evangelicals.

Starting with the east, Canada’s four Atlantic Provinces attract tourists because of their spectacular coastlines, picturesque cities and villages, and inviting green farms and orchards. But they first attracted colonists because of their fish and timber, as well as their strategic location at the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River.

It was here that evangelicalism first came to Canada in the eighteenth century. Colonists in the outlying villages of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick felt cut off from their fellow Yankees in the revolutionary 13 colonies to the south. Henry Alline (1748-84) born in Rhode Island and raised in Nova Scotia, brought a message of God’s radical favor upon those whom the world had ignored. His work sparked the Canadian “Great Awakening” in the Maritime region.

Unlike the well-educated leaders of the awakenings in the American colonies a generation earlier—such as Oxford graduate George Whitefield or Yale man Jonathan Edwards—these Maritime revivalists left behind no profound theological or homiletical works. But they did foster a warm piety and expressed it in gospel hymnody. Alline himself composed more than 500 hymns, a few of which are still known by heart among Maritime Baptists 200 years later:

He pluck’d me from the jaws of hell With his almighty arm of pow’r; And O! no mortal tongue can tell The change of that immortal hour!

Then I enjoy’d a sweet release From chains of son and powers of death; My soul was killed with heav’nly peace, My groans were turn’d to praising breath.

Leaders of this Great Awakening did more than preach individual salvation; they sought to transform the little settlements of the Maritime hinterland into loving communities of worship, mutual edification, and social service. Their success stamps Maritime culture to this day with evangelical orthodoxy, piety, and social concern.

QUEBEC’S QUIET REVOLUTION

As one travels up the Saint Lawrence, the huge province of Quebec (almost three times the size of France) stands as a kind of fortress against evangelicalism. Until the 1960s, this officially French-speaking province was dominated by the Roman Catholic Church—to the extent that public education was ceded to it by successive provincial governments. Notorious laws—some passed just decades ago—enabled priests and their Catholic partisans to incite local mobs and law-enforcement authorities to harass and even arrest Protestant evangelists in their communities.

Since Quebec’s “quiet revolution” began in the 1960s, however, the province has undergone remarkably rapid secularization. According to University of Lethbridge sociologist Reginald Bibby (a Canadian combination of George Barna, George Gallup, and Robert Wuthnow), almost nine in ten Quebecois attended church on a weekly basis as late as 1957. Fewer than three in ten do so today. The challenge for the few evangelical churches in Quebec today is to evangelize an increasingly secular population, not to convert a Catholic one.

The cultural revolution of the sixties affected a wide range of Canadian institutions, including the church. The liberalization of divorce laws and sexual ethics, the increase of government-sponsored gambling, the secularization of public schools and Universities, the availability of abortion virtually on demand, the progressive dismantling of Lord’s Day legislation—all have shown Canadian Christians that they no longer command their culture as they did in the nineteenth century.

As Bibby has detailed, well over 80 percent of Canadians now maintain a nominal allegiance to the Christian faith. A recent article in Maclean’s magazine (Canada’s answer to Time) recently declared that Canada is an “overwhelmingly Christian nation.” But many Canadians know little and practice less of historic Christianity. “Canada emerged late out of the Victorian periods mused historian John Webster Grant, but Canada seems to have made up for lost time. Religion generally figures in the news only when it is extreme (which is rare in Canada) or immoral (which, sadly, is not so rare).

THE CENTER OF THINGS

It is a long day’s drive—600 miles—from Quebec City to Windsor, at the southern tip of Ontario, across from Detroit. Yet 60 percent of the Canadian population lives along this corridor, only 2 percent of the country’s area. Canada’s capital city, Ottawa, is in Ontario, and the financial, political, and demographic center of power is clearly here, in the neighborhood of metropolitan Toronto.

In the nineteenth century, evangelical Anglicans, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists dominated Ontarian culture. They founded hospitals, orphanages, universities, and missionary societies. And their churches—almost all in the same “Ontario Gothic” architectural style—still loom in the province’s downtowns.

The skyscrapers of the banks, though, loom higher still. In populous Ontario, evangelicals no longer run the show. The same is true nationally. Of the Canadian population of 26 million, Protestant evangelicals may number—depending on which survey you use—as few as 10 percent.

In no sphere is this more obvious than in education. A century ago several of Canada’s provinces, including Ontario, established public-school systems that were explicitly Protestant Each day began with the Lord’s Prayer, and teachers promoted a generic, mildly evangelical faith. Substantial Roman Catholic minorities, as in Ontario, received government support for their own, “separate” schools (as they are still called).

Today, though, the public schools have been fully secularized. Many evangelicals believe the current system threatens the faith of their children. Yet the Ontario government continues to resist their efforts to obtain tax support for new, religiously oriented schools—while the historic support for Roman Catholic schools continues.

That provincial wariness holds for postsecondary education. Since the Second World War, Dutch Reformed Christians have supported a private undergraduate college, Redeemer, and a graduate school, the Institute for Christian Studies, which, incredibly, cannot receive official accreditation to grant standard university degrees.

Ontario yet provides the home—or at least headquarters—of many denominations and evangelical institutions. One of the continent’s oldest Bible schools and one of Canada’s largest seminaries, Ontario Bible College and Ontario Theological Seminary, serve a wide range of Canadian evangelicals just north of Toronto, as do a number of other denominational schools in the province.

Southern Ontario also hosts the offices of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (EFC), a parallel to the National Association of Evangelicals in the United States. For 30 years, EFC. has linked the most important evangelical institutions across the country. Not surprisingly, Canadian evangelicals—along with Canadians in general — look to Ontario as the country’s hub.

THE PRAIRIES’ EVANGELICAL RESURGENCE

The three large provinces to the west-Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta—have long welcomed immigrants from all over the world to tend their wheat fields and mine their ores. Evangelicalism on the prairies has been influenced in significant ways by these immigrants, and perhaps by no group more than the Mennonites.

Look up the “Churches” section of the Yellow Pages for Winnipeg, a city of 650,000 and the gateway to the west, and you will find the three largest churches in the nation represented in order. Roman Catholics have the most congregations listed (roughly half of Canada is Catholic). The United Church of Canada comes next; one in five Canadians holds some allegiance to this decades-old amalgam of Methodists, Congregationalists, and most of the Presbyterians. The Anglican Church in Canada (one in ten nationally) accounts for the third-largest number of congregations.

An equal number of Winnipeg churches, though, are Mennonite. Indeed, Southern Manitoba could be called the Mennonite capital of the world. While they number fewer than 1 percent of the national population, Mennonites add their Anabaptist flavor to evangelicalism all across the prairies, as well as in southwestern Ontario. Much of the strength of evangelicalism in western Canada, says Trinity Western University historian Bob Burkinshaw, “is due to the number of people of Mennonite background in a whole range of churches, such as the Christian and Missionary Alliance, Baptist, Pentecostal, and independent.”

As the Trans-Canada Highway moves west out of Manitoba on the prairie tableland, it passes through the tiny town of Caronport, Saskatchewan. Towering over the village is the peaked roof of one of western Canada’s largest auditoriums, the main building of Briercrest Bible College. As Canada’s largest Bible school, it joins dozens of others in training more than 7,000 students each year. Because Canada has only a handful of Christian liberal-arts colleges and seminaries, Bible schools have long been Canadian evangelicalism’s dominant form of post high-school education. Alberta, in particular, seems to be experiencing a resurgence of evangelical strength Calgary, for example, has recently seen remarkable enthusiasm for “concerts of prayer” and substantial church growth. In other major prairie cities as well, the new churches going up tend to have signs with words like “Pentecostal,” “Christian and Missionary Alliance,” “Mennonite Brethren,” and “Baptist.”

THE LEADING EDGE

Two apparently contradictory trends come together strikingly in Canada’s westernmost province, British Columbia. Here is Canada’s land of new beginnings, of a milder climate, of a West Coast lifestyle that many Americans would easily recognize. “Beautiful British Columbia,” as its tourism office tirelessly proclaims, is where the vast majority of Canadians say they would move if they left their current home.

Most British Columbians have left more than their previous residence: they have left organized religion. Who wants to go to church when one can hike, ski, or windsurf amid spectacular surroundings? And since Vancouver and Victoria are Canada’s most expensive cities, people commonly work overtime or even hold a second job. British Columbia thus is Canada’s most secular province. The polls show that the leading religious choice among British Columbians is “no religion.”

Yet, as this province perhaps serves as a bellwether for Canada’s continued secularization, a countervailing trend bears watching as well. For the second-most-popular religious option among British Colombians is evangelical Christianity.

Part of this can be accounted for by looking in the lower Fraser Valley, now a southeastward extension of metropolitan Vancouver and heavily populated by immigrants from the prairies. Here grow Mennonite Brethren, Alliance, and other churches seating hundreds and even thousands—remarkable statistics in a country with virtually no “megachurches,” and in which 90 percent of the churches have fewer than 250 people in attendance on a Sunday morning.

Part of evangelicalism’s vitality in British Columbia comes also from Christian immigrants from the other direction: the Pacific Rim. Virtually every urban center in Canada is being reshaped by an influx from Hong Kong, Singapore, and Korea. Canadian evangelicalism is changing as well. Schools like Vancouver’s Regent College have begun programs and hired faculty to serve these new communities.

GOOD NEWS IN THE BAD NEWS?

This relative strength of evangelicalism in British Columbia reflects a national reality as well. Most Canadians continue to identify with a small number of Christian denominations. The Roman Catholic, United, and Anglican churches claim the nominal allegiance of about three-quarters of the population. Lutherans, Orthodox, Presbyterians, and Baptists make up much of the rest.

But look inside the doors of the churches on Sunday morning to see who is there. Ask people, “Who actually prays and reads the Bible regularly and gives money to Christian causes?” The answer underscores that evangelicalism—both within the former mainline Protestant denominations and the uniformly evangelical ones—is now the dominant orientation in Canadian Protestantism.

This relative dominance, however, has come only at the expense of a decline in mainline churches’ active membership. Popular broadcasters like David Mainse and Terry Winter remain unknown to the nation at large. InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Campus Crusade for Christ, Youth for Christ, and the Navigators lead the way in Christian work among students, but higher education in Canada remains overwhelmingly secular and pluralistic. Groups like EFC, Citizens for Public Justice, and Focus on the Family exert political pressure, but few Christian lobbyists besides the EFC’s Brian Stiller have any significant access to the powerful in government and mass media.

Canadian evangelicalism therefore faces the daunting prospect of re-evangelizing a country it once deeply influenced. But it does so with some remarkable advantages.

First, despite their diversity—whether Anglicans, Mennonites, Presbyterians, or Pentecostals-Canadian evangelicals belong to a network that connects denominations, congregations, parachurch organizations, and individuals. Unlike the United States with its “wheels within wheels,” evangelicals in Canada tend to recognize one another as part of one large, if sometimes fractious, movement.

Second, Canadian evangelicals work together with very little of the separatistic militancy of fundamentalism. Few Canadian denominations have been divided; few political campaigns have been waged; few supporters have been found for the kind of absolutist Christianity that has affected American evangelicalism to this day. This moderation is partly due to the fact that Canadian evangelicals have rarely been able to afford the luxury of splitting up institutions and creating new ones.

Third, even traditions that elsewhere produce extremes seem to moderate in the Canadian climate. In an earlier generation, for instance, J. E. Purdie (1880-1977) was renowned for his efforts to keep Pentecostalism connected with the heritage of historic Christianity. As founding principal of the Pentecostals’ first full-time Bible college in Winnipeg, he influenced several generations of clergy. Himself a graduate of the evangelical Anglican Wycliffe (theological) College in Toronto, Purdie was widely reported to have taught his Pentecostal students from Presbyterian Charles Hodge’s Systematic Theology while retaining his Anglican clerical collar. Pentecostals now lead Canadian evangelicals in church growth and are welcome contributors to major transdenominational institutions as well.

But Canadian evangelicalism also faces challenges from within. Leaders among Pacific Rim immigrants and French-Canadians are still virtually invisible at the regional and national levels. The vast North’s scattered population remains nominally Christian for the most part, with some modest evangelistic success by Pentecostals, Baptists, and other evangelicals who carry on the tradition of missions established by Roman Catholics, Anglicans, and others. It remains to be seen how much these various Christian communities will assimilate into the prevailing AngloCanadian styles of evangelicalism.

Other issues—Pentecostal/charismatic phenomena, gender roles, homosexuality, Christian schooling—prompt tensions and even some divisions among denominations and parachurch organizations. Yet Canadian evangelicals do not generally polarize over issues that divide many Americans, such as inerrancy or eschatology. Canadian evangelicals will likely continue to cooperate when they can—particularly in evangelism, worship, and political action on behalf of family issues-and go their own ways with little recrimination when they cannot.

Evangelicalism in Canada continues to grow in numbers, networks, and sophistication. Whether or not Canada’s slide toward secularization bottoms out, evangelicals will continue to attract new seekers. They will continue to find their way to the table of pluralism to speak with cogency and compassion to a society driven with racial, regional, and economic differences. They may not enjoy the threat resources of personnel and finances and the more benign environment that help Americans produce rich and exotic varieties of evangelicalism. But there is good work going forward nonetheless, even as we button up our jackets.

John G. Stackhouse, Jr., is associate professor of religion at the University of Manitoba, and author of “Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century” (University of Toronto).

Copyright © 1994 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

ctjul94mrw4T80185619