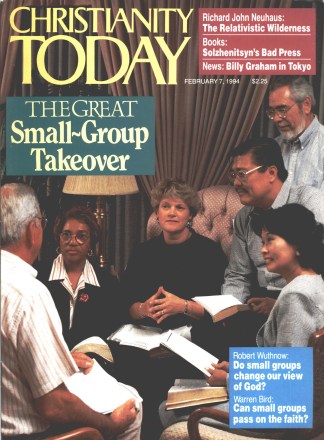

Small groups continue to multiply, but are they helping the church pass on the faith?

Last fall, a certain scale tipped at Trinity Baptist Church, Mount Pleasant, Texas. For the first time in its 11-year life, this Southern Baptist church of about 350 worshipers counted more adults involved in small groups than it did in Sunday school.

Sunday school is strong at Trinity Baptist, with 60 percent of worship attendee participating in any given week. But attendance in other kinds of small groups, whether meeting on-premises or in homes, has steadily inched even higher.

This change neither surprises nor disappoints Reggie McNeal, until recently Trinity’s senior pastor. Of Trinity Baptist’s 27 non-Sunday-school small groups, McNeal himself typically led only one or two. “But every key leader in the church has been with me at one time or another in some kind of small-group discipleship,” he says.

According to a recent three-year, Lilly Endowment-funded Gallup study, more adult churchgoers today are involved in Bible studies and self-help groups than in Sunday school. This broadening of options, an expression of our “megachoice” era, represents both a significant historical movement and an important dimension in the culture of North America itself.

It is not the first time America has seen such significant change. Many Christians are surprised to learn that the American Sunday-school movement, started in the 1790s, has gone through several dramatic changes in the many decades since. The purpose changed from literacy education to evangelization, then changed again to focus on Christian instruction. Classes moved from rented halls to church buildings, and the participants expanded from the poor to all social classes.

Small groups are again significantly altering the landscape of the North American church. This continentwide emphasis is even more diverse than Sunday school was during its infancy. Advocates and critics alike are not even agreed whether it is a simple extension of the Sunday school or its eventual successor.

Culture shift

Understanding small groups’ impact begins with realizing how pervasively the movement affects our culture. According to sociologist Robert Wuthnow, the movement is effecting a “quiet revolution.”

George Gallup, Jr., likewise links small groups to societal changes.”If the sixties represented the ‘Movement Decade,’ ” he notes, “the seventies the ‘Me Decade,’ and the eighties the ‘Empty Eighties,’ then perhaps the nineties will become known as the ‘Decade of Healing.’ ” Gallup believes such a label is appropriate in view of the millions of Americans who have joined small nurturing and caring groups seeking help for psychological, physical, emotional, or spiritual problems.

Why do so many seek the solace of small groups? Gallup cites several reasons, all dealing with the impersonalness and fragmentation of today’s society: (1) We live in an addicted society—whether to chemicals or to self-indulgence; (2) six out of every ten new marriages will end in divorce; (3) seven out of ten people are so detached from their communities that they do not know their neighbors; (4) loneliness is widespread; and (5) privatism contributes to a go-it-alone philosophy in religious matters. “The small-group movement,” concludes Gallup, “appears to be bringing us back together, answering what seems to be one of the central needs of our era—the need for an intimate and healing community.”

Carl George, director of the Charles E. Fuller Institute and proponent of the “metachurch” paradigm (which focuses on leadership development through small groups), points to an additional, even more basic need in today’s culture: “In an alarming number of cases, the biological family is not functioning well: people are increasingly unable to find the support, acceptance, belonging, positive role modeling, and sense of normalcy they need from home. A cell [small group] is a place where people have enough reference points socially to find themselves sustained emotionally and spiritually.” While the emotional support of a small group is different from that of a family, a group, says George, provides “a context for meeting needs for intimacy and trust.”

Such changes mean that Sunday school, while still alive and well, is no longer the primary manifestation of the small-group movement in America. Something like 40 out of every 100 American adults belong to small groups (and an additional 7 of 100 are interested in joining), according to the Gallup study. In the study, a small group is defined as one that meets regularly and provides caring and support for its members. Only 24 of those 40 people (60 percent) are in a church-related group. The rest of the groups may gather as a literary discussion group, as friends who do Step Reebok exercises and then go out for coffee, as a senior’s travelogue club, or in any number of other contexts that have no organizational connection with a church.

Nevertheless, the last 40 years have given rise to a distinct small-group movement in North American Christianity. Its proponents share a loosely connected, variously defined passion that emphasizes lay-led groups, whether on- or off-premises, as pivotal to a church’s sense of community, discipleship, evangelism, pastoral care, and assimilation.

Indeed, while the story of Trinity Baptist would have been unimaginable before the 1950s, highly unusual in the 1960s and 1970s, and denominationally embarrassing in the 1980s, in the 1990s it is commonplace. Many church leaders realize that much of the work of the church is best accomplished in the context of a group, particularly one that is small.

Today’s multifaceted small-group movement, however, gives rise to some questions: Are small groups truly helping the church to pass on the faith, encourage biblical literacy, and form committed disciples of Jesus Christ? How effective are they as a tool for outreach? And are they driven more by God’s calling for his church or by the vagaries of our secular culture?

Spiritual kinship?

Most advocates of cell-sized church groups point to Scripture as the source for their emphasis. In his books, Elmer Towns, long-time chronicler and theorist of the Sunday-school movement, looks to Acts 2 and other passages to demonstrate that the New Testament church was composed of both “cell” and “celebration.” To him, small groups—ideally the Sunday school—are foundational to any healthy church worship, edification, and witness.

Others, such as Carl George, emphasize the New Testament teachings on the body of Christ and suggest that small groups are the ideal arena for their expression. George points to the 59 “one-another” commands that appear there.

Other small-group proponents go back further in sacred history, emphasizing the role of the synagogue in Jewish culture. Ten men, along with their families, could form a synagogue. The resulting sense of community formed a binding social context. Church-growth theorist C. Peter Wagner builds on that concept by calling today’s small group a “spiritual kinship unit.”

One of the most visible and most researched expressions of North American small groups came to be John Wesley’s class meetings. Howard Snyder, in The Radical Wesley and Patterns for Church Renewal, outlines Wesley’s organizational plan: Wesley started with societies (based on a large geographic area), which were subdivided into groups of 12 members called classes. Those within a class who professed assurance of salvation were organized into bands. Finally, band members who “appeared to be making marked progress toward inward and outward holiness” were formed into intimate cell groups called select societies.

According to Snyder, “The class meeting was the cornerstone of the whole edifice. The classes were in effect house churches—not classes for instruction as the term class might suggest—meeting in the various neighborhoods where the people lived.” These classes usually met weekly.

For various historical reasons, classmeeting momentum waned, but not without forging a critical link in Methodism’s growth. The denominational forerunner of today’s United Methodist Church was one of the dominant religious bodies in the United States from the mid-1800s to the 1960s.

By the late 1800s, the Sunday-school movement was gaining national prominence, by the 1920s becoming the dominant small-group movement in America. Because it was not limited to only one or two denominations, it dwarfed the scope of Wesley’s class meetings.

“By 1900,” says Lyman Coleman, developer of Serendipity Bible-study resources, “the Sunday-school movement had developed a cradle-to-the-grave emphasis with a graded curriculum based on the public-school format. By 1950, 75 percent of church members were involved in the Sunday school. It was the major force for evangelism and assimilation in the church. The few alternatives, such as cottage prayer meetings, were not perceived as being the small groups that they in fact were.”

The forties and fifties also gave rise to a number of organically unrelated parachurch movements: the Oxford group, Alcoholics Anonymous, Faith at Work, the Navigators, InterVarsity and numerous others. Says Coleman, by the 1960s, and even more so by the 1970s, the Sunday school, with its emphasis on age categories, on-site location, and Sunday-only meetings, was clearly in decline. At the same time, a new model was rising, with an emphasis on “life-stage categories,” on- or off-premises meetings, and—to borrow from a recent term by Lyle Schaller—the seven-day-a-week church.

Struggling for definition

Roberta Hestenes, Eastern College president and popularizer of the “covenant” model of small groups, notes, “Trying to define the small-group movement is like describing the proverbial elephant. Your perspective all depends on which piece you are experiencing and seeing.” Snyder argues that the small-group movement has changed dramatically over the past 20 years and “now nearly defies definition.”

Wuthnow/Gallup statistics confirm the diversity. Small groups include 800,000 Sunday-school classes (involving 18–22 million people), 900,000 Bible-study groups (15–20 million people), 500,000 self-help groups (8–10 million people), 250,000 political/current-events groups (5–10 million people), and 250,000 sports/hobby-event groups (5–10 million people).

Nowhere in the small-group movement is there more diversity than in the definition of small and of group. Lyle Schaller, prolific author and church consultant, insists that small groups are technically seven people or less. Carl George opts for 8 to 10: “By the time a group reaches 17 people, it no longer functions as a small group.… Much experience suggests that intimacy is significantly hampered as group size exceeds a dozen.”

Definitions of group are equally divergent. Ralph Neighbour, one-time Southern Baptist curriculum writer and author of numerous books, including Where Do We Go from Here?, argues for an intensive approach, what he calls a “pure” cell-church movement. Small groups would replace what he calls “program-based” church structures, including Sunday school.

Carl George takes a more generic approach to small groups, similar to Wuthnow’s. “The typical church,” he says, “has dozens of regular gatherings that may not be formally recognized as small groups, but easily have the potential to function as a group in providing emotional care, gift-based, ‘one-another’ ministry, teaching, evangelism, discipleship, and assimilation.”

Why so much divergence of perspective? No founding or pre-eminent leader has led the sprawling small-group movement. It has flourished without one person or organization serving as an equivalent to what Bill Hybels and Willow Creek Church are to today’s “seeker-service” movement. And small groups are trendy in the widest possible range of denominations, regions, social classes, and ethnic groups (the one major exception being first-generation immigrants for whom the extended family seems to obviate a voluntary small group). This diversity allows churches to respond flexibly to varied needs and opportunities. It also means churches must guard against merely responding to the currents of our culture.

Keeping groups on track

In the midst of this diversity, can any principles distinguish small groups that function healthily from those that do not? “There are many ways to encourage, build, and run a small-group system,” says Hestenes. “The need for minimally trained and supported leadership is always present.”

Clarity about a group’s reason for being is also important. “When the purpose of a congregation’s small groups is outreach,” says Hestenes, “it’s very appropriate to have groups that are deliberately open all the time. At the same time, groups tend to grow deeper when the membership remains stable for a while.”

But what in particular should be emphasized? Options and purposes vary greatly:

• Reaching out to nonchurchgoers. Lyman Coleman believes small groups are particularly well suited to draw in those on the periphery or outside a church. Coleman says he has identified 130 “ ‘doors’ where people can get on the ‘subway line’ that feeds into the ‘center city’ of a church,” referring primarily to support and recovery groups. “In the next 10 years, the church will learn how to open those doors, or we’ll miss the greatest opportunity since the first century.”

Judy Hamlin, a Texas-based small-group consultant and author of 14 books on small groups, believes churches need to think of groups evangelistically. She finds a direct link between cell health and evangelistic intent—an orientation to reaching out helps a group stay vital. “Small groups,” she says, “offer a platform to build relationships that reach people for Christ.” As such, the typical small-group leader needs to be known and gifted not so much for teaching abilities “but as a person of compassion.”

• Assimilating newcomers. Charles Arn, president of the Monrovia, California-based Church Growth, Inc., and editor of The Growth Report, says that “in more cases than not, small groups actually distract a church from reaching and assimilating new people.” Because most churches do not think of groups in terms of how many people they can bring into the church family, Arn argues, “they divert considerable resources, energy, and focus away from outreach and evangelism.”

Arn’s solution is “for churches to be regularly starting new groups for their new people.” His rule of thumb: “20 percent of all groups should have been started within the past two years. That way, newcomers will have opportunity to find a place to fit in and grow.”

John Vaughan, professor of church growth at Southwest Baptist Seminary, Bolivar, Missouri, confirms this strategic role of small units. “The small group is the most likely place for assimilation and equipping for ministry to occur,” he says. “Large churches have, in most cases, mastered the dynamics of smaller groups. The large churches that survive, achieve and sustain their growth through effective subgroupings.”

At the same time, he warns against shifting away from Sunday school as the preferred forum for those groups. “America’s fastest-growing churches demonstrate that Sunday-school groups continue to be the premier small-group growth model in the nation.” He notes that some churches emphasize home groups, some Sunday school, but only a few do both well. “If the Assemblies of God and Southern Baptists, for example, were now to adopt the home-cell-group model as their primary emphasis, it could be a tragedy.”

• Nurturing disciples. This is the area many most naturally think of in connection with small groups. Ron Habermas, Christian-education expert and professor of biblical studies at John Brown University, Siloam Springs, Arkansas, suggests that small groups allow for a certain “sophistication” in the learning process. While they can degenerate into mere sharing of feelings, he says, “small groups force people to think about and articulate what they believe in a way not usually possible with sermons and traditional Sunday-school lectures. They prompt dialogue and can bring a person to greater ownership of beliefs.”

Others see small groups as ideal settings for “spiritual formation” and accountability. Organizations such as the Navigators or Richard Foster’s Renovaré emphasize them as ideal for nurturing Christian growth. And many pastors, notes George, see small groups as ideal “laboratories” for developing church leaders.

What can go wrong

Whatever the potential uses and benefits of small groups, observers also raise some cautions.

Today’s small groups may lack the stability of yesteryear’s networks of family and church. They may be more concerned with the emotional state of the individual than with spiritual formation; some are prone to accent subjective experiences more than objective truths. Theologian J. I. Packer believes that when churches encourage people to join small groups now, as opposed to 25 years ago, “it is not so much thought of as a way of seeking God as much as seeking Christian friends. The vertical axis is not emphasized as much as the horizontal axis.”

While Wuthnow found that adult Bible studies are among the most popular groups—almost two Bible studies for each one self-help group—small groups do little to increase the biblical knowledge of their members. Says Hestenes, who has been involved in the small-group movement since her conversion through a college InterVarsity chapter, “Small groups easily become too faddish or too psychologically oriented whenever they are not grounded in the authority of Scripture or the centrality of God, and in the need for redemption, conversion, and the transforming power of the Holy Spirit.”

Another potential pitfall is spiritual abuse. Dave Johnson and Jeff VanVonderen have helped lead a Minneapolis-area church to significant growth primarily by the preaching of grace and the offering of recovery groups. But in their book The Subtle Power of Spiritual Abuse, they point out numerous examples of churches and groups that control, manipulate, and misuse power in a way that could be called spiritually abusive. People involved in cults, in the charismatic shepherding movement, and in the Boston Church of Christ likewise testify to ways that small groups can be driven by warped, sometimes sub-Christian, motives.

What of the future?

To what extent are small groups here to stay? George Barna, pollster and author, created something of a stir last year by suggesting that the small-group movement may be waning. A 1993 survey he conducted pointed to an overall drop in small-group participation in churches—the first downturn in the five years he has been conducting the poll. He speculated the drop can be accounted for by a tendency toward weak teaching, confusion of purpose, lack of leadership, and even such mundane concerns as inadequate childcare. Many question, however, whether a one-year fluctuation is conclusive.

In the meantime, publishing houses, from those of the Southern Baptists to InterVarsity Press, continue to sell an ever-widening array of small-group resources. Some churches, including Willow Creek Community Church in suburban Chicago, which has the largest weekend attendance of any church in North America, are encouraging all members to join small groups. The newly organized Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan hands out brochures entitled, “If you’re not in a small group, you’re not in the church.”

Experimentation with new approaches will doubtless continue. Paul Walker, pastor of Atlanta’s Mount Paran Church of God, says that the church (which now sees a weekly attendance of 11,000 on five “campuses”) emphasized small groups continually during his more than 30 years there. But that emphasis took new forms. “We moved from the 1960s,” says Walker, “with small Sunday-school classes that were group oriented, into the 1970s, with home-fellowship groups, into the 1980s, with more support- and recovery-group models, to now, with what we call a multiple-group model, which has a little bit of everything.”

In the wider church, adapting and experimenting with new forms can be a sign of health and strength. It can also signal lack of purpose or direction. However much the small-group movement has grown and flourished, it stands at a critical juncture. As it continues to help many people discover deeper levels of community and emotional wholeness, it must also find new ways to meet the churches’—and our culture’s—need for grounding in the unchanging truths of the Christian faith.

Paul Brand is a world-renowned hand surgeon and leprosy specialist. Now in semiretirement, he serves as clinical professor emeritus, Department of Orthopedics, at the University of Washington and consults for the World Health Organization. His years of pioneering work among leprosy patients earned him many awards and honors.