As a child, Kay Brigham read Admiral of the Ocean Sea, the Pulitzer prize-winning biography of Columbus, by naval historian Samuel Elliott Morrison, a good friend of her sea-captain father. This early interest in the Italian explorer never left her. As a Woodrow Wilson Fellow at the Claremont Graduate School, she earned a master’s in Spanish language and history, and later continued her studies at the University of California at Berkeley in romance languages and literature. But as a student of Bible prophecy, Brigham was particularly interested in Columbus’s handwritten Book of Prophecies. Her search took her to Madrid and Seville, where she was able to examine a rare facsimile—complete with rat holes. Her resulting books, Christopher Columbus: His Life and Discovery in the Light of His Prophecies and Christopher Columbus’s Book of Prophecies: Reproduction of the Original Manuscript with English Translation, were recently published by Libros CLIE of Barcelona (available in the U.S. from TSELF of Fort Lauderdale).

At one point Columbus experienced a significant personal crisis. How did that shape his sense of mission?

On his third voyage, Columbus found Hispaniola in chaos. Columbus’s brothers, who were governing the island, had lost all control. A tremendous tension had been created between the colonists and the native Americans. Word got back to Spain about these problems, and they sent over representatives. Columbus, along with his brothers, was shipped back to Spain in chains. This was the most humiliating experience of Columbus’s entire life. He refused to have the chains removed until he had a personal audience with the king and queen. Between the time he was shipped back and his audience with the Spanish crown, he had a lot of time to think, much of it spent in a monastery in Seville.

It was in 1502, at this time of personal crisis, that he put together The Book of Prophecies. The Prophecies is extremely important because it reveals the essence of Columbus. It reveals an extraordinary intellectual and spiritual formation.

The Book of Prophecies seems like a compilation of Scripture and other quotations with few of Columbus’s own words. Did you have to read between the lines to analyze what was going through his mind?

Columbus was a prolific writer, and so we do not have to read between the lines. There is a prefatory letter in the Prophecies addressed to the king and queen of Spain in which he clearly explains his goal in the compilation: to explain his vision of history and his enterprise of the Indies and his role in the scheme of world history.

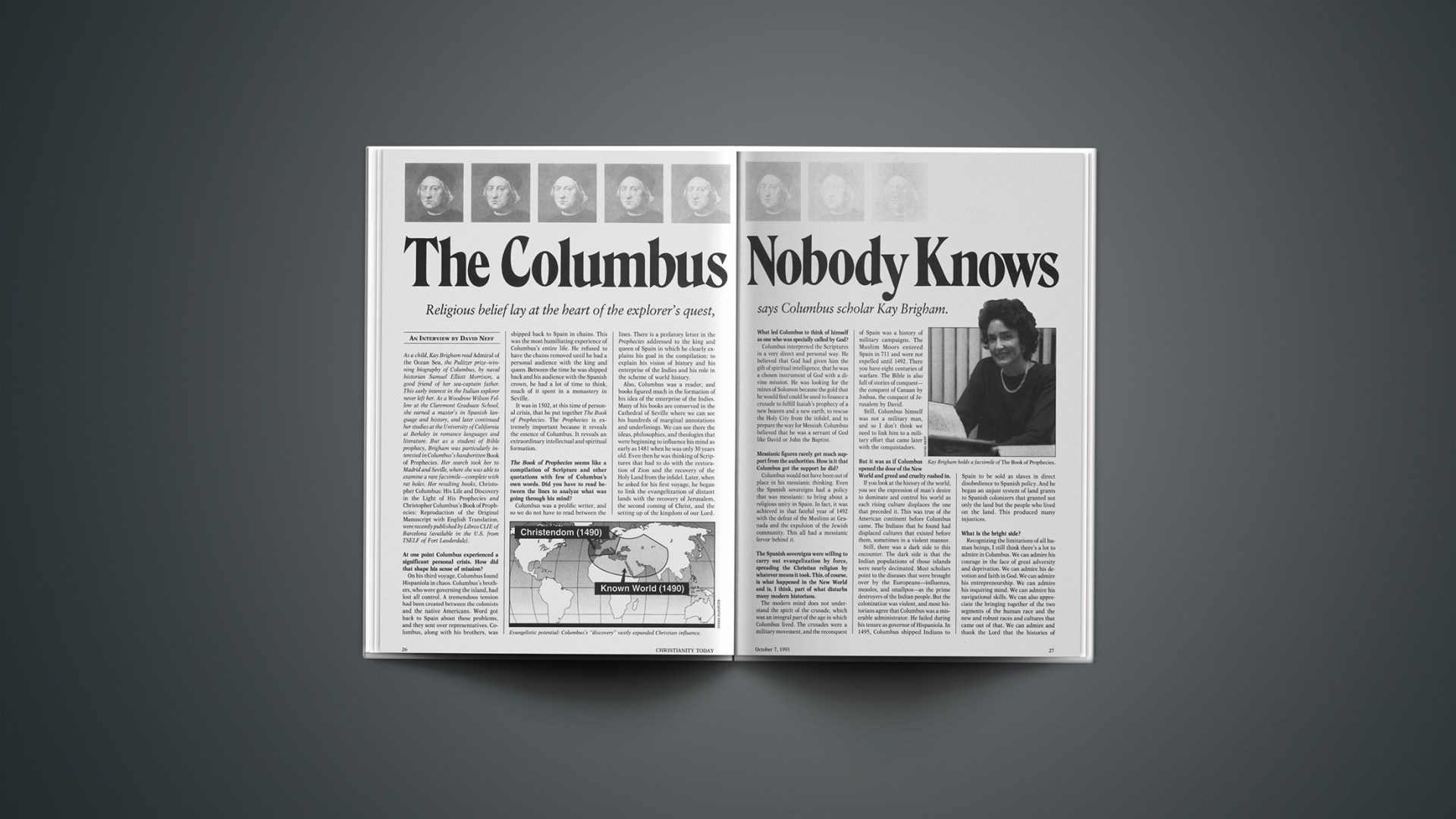

Also, Columbus was a reader, and books figured much in the formation of his idea of the enterprise of the Indies. Many of his books are conserved in the Cathedral of Seville where we can see his hundreds of marginal annotations and underlinings. We can see there the ideas, philosophies, and theologies that were beginning to influence his mind as early as 1481 when he was only 30 years old. Even then he was thinking of Scriptures that had to do with the restoration of Zion and the recovery of the Holy Land from the infidel. Later, when he asked for his first voyage, he began to link the evangelization of distant lands with the recovery of Jerusalem, the second coming of Christ, and the setting up of the kingdom of our Lord.

What led Columbus to think of himself as one who was specially called by God?

Columbus interpreted the Scriptures in a very direct and personal way. He believed that God had given him the gift of spiritual intelligence, that he was a chosen instrument of God with a divine mission. He was looking for the mines of Solomon because the gold that he would find could be used to finance a crusade to fulfill Isaiah’s prophecy of a new heaven and a new earth, to rescue the Holy City from the infidel, and to prepare the way for Messiah. Columbus believed that he was a servant of God like David or John the Baptist.

Messianic figures rarely get much support from the authorities. How is it that Columbus got the support he did?

Columbus would not have been out of place in his messianic thinking. Even the Spanish sovereigns had a policy that was messianic: to bring about a religious unity in Spain. In fact, it was achieved in that fateful year of 1492 with the defeat of the Muslims at Granada and the expulsion of the Jewish community. This all had a messianic fervor behind it.

The Spanish sovereigns were willing to carry out evangelization by force, spreading the Christian religion by whatever means it took. This, of course, is what happened in the New World and is, I think, part of what disturbs many modern historians.

The modern mind does not understand the spirit of the crusade, which was an integral part of the age in which Columbus lived. The crusades were a military movement, and the reconquest of Spain was a history of military campaigns. The Muslim Moors entered Spain in 711 and were not expelled until 1492. There you have eight centuries of warfare. The Bible is also full of stories of conquest—the conquest of Canaan by Joshua, the conquest of Jerusalem by David.

Still, Columbus himself was not a military man, and so I don’t think we need to link him to a military effort that came later with the conquistadors.

But it was as if Columbus opened the door of the New World and greed and cruelty rushed in.

If you look at the history of the world, you see the expression of man’s desire to dominate and control his world as each rising culture displaces the one that preceded it. This was true of the American continent before Columbus came. The Indians that he found had displaced cultures that existed before them, sometimes in a violent manner.

Still, there was a dark side to this encounter. The dark side is that the Indian populations of those islands were nearly decimated. Most scholars point to the diseases that were brought over by the Europeans—influenza, measles, and smallpox—as the prime destroyers of the Indian people. But the colonization was violent, and most historians agree that Columbus was a miserable administrator. He failed during his tenure as governor of Hispaniola. In 1495, Columbus shipped Indians to Spain to be sold as slaves in direct disobedience to Spanish policy. And he began an unjust system of land grants to Spanish colonizers that granted not only the land but the people who lived on the land. This produced many injustices.

What is the bright side?

Recognizing the limitations of all human beings, I still think there’s a lot to admire in Columbus. We can admire his courage in the face of great adversity and deprivation. We can admire his devotion and faith in God. We can admire his entrepreneurship. We can admire his inquiring mind. We can admire his navigational skills. We can also appreciate the bringing together of the two segments of the human race and the new and robust races and cultures that came out of that. We can admire and thank the Lord that the histories of Canada, the United States, and the numerous American republics were initiated. In fact, we can admire the fact that the great missionary movement that issued from this part of the world began with the second voyage of Columbus when he brought with him missionaries to these lands.

Some would have us believe that the New World was a paradise before Columbus came. What was it like?

There was the same greed and violence over here as there was in all the rest of the world. In fact, on Guadeloupe, on the second voyage, Columbus discovered widespread cannibalism. The Carib people would raid the gentler Taino groups in the island, enslave them, and eat them. And later on in Mexico, Cortés, for all his cruelty, was horrified by the human sacrifice that was practiced on a grand scale in the Aztec culture.

Much of the concern over the celebration of the five-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s arrival seems not so much over Columbus as a person as it is over difficult aspects of the history that can be dated to that time.

Many groups are exploiting the quincentenary for their particular causes. But I think we should look at history in its own context, and we should present both the good and the bad aspects of what happened. I don’t think any of us are out to extol injustice. But we must not miss the good, the heroic, and the noble, and there was much heroic and noble in the encounter. And that, I think, we should celebrate.

At the end of your book, you call for a renewed vigor in promoting Christianity’s influence around the world in imitation of Columbus. What can we learn from Columbus in this regard?

Christianity is in a precarious position if we don’t proceed in the spirit of Columbus, with his faith in God and his sense of mission. If Christians ever lose this, then we, but for the sovereignty of God, are lost. Only a small part of the known world in Columbus’s day was under Christian influence. And the discovery of America doubled the geographical sphere of that influence. You have to ask, if Columbus had not arrived on these shores, what would have happened to Christianity? I believe God raised up this man to extend the gospel to those regions that had never heard.

Eugene H. Peterson is pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church, Bel Air, Maryland, and author of A Long Obedience in the Same Direction (InterVarsity) and Answering God (Harper & Row), both of which are about the Psalms.