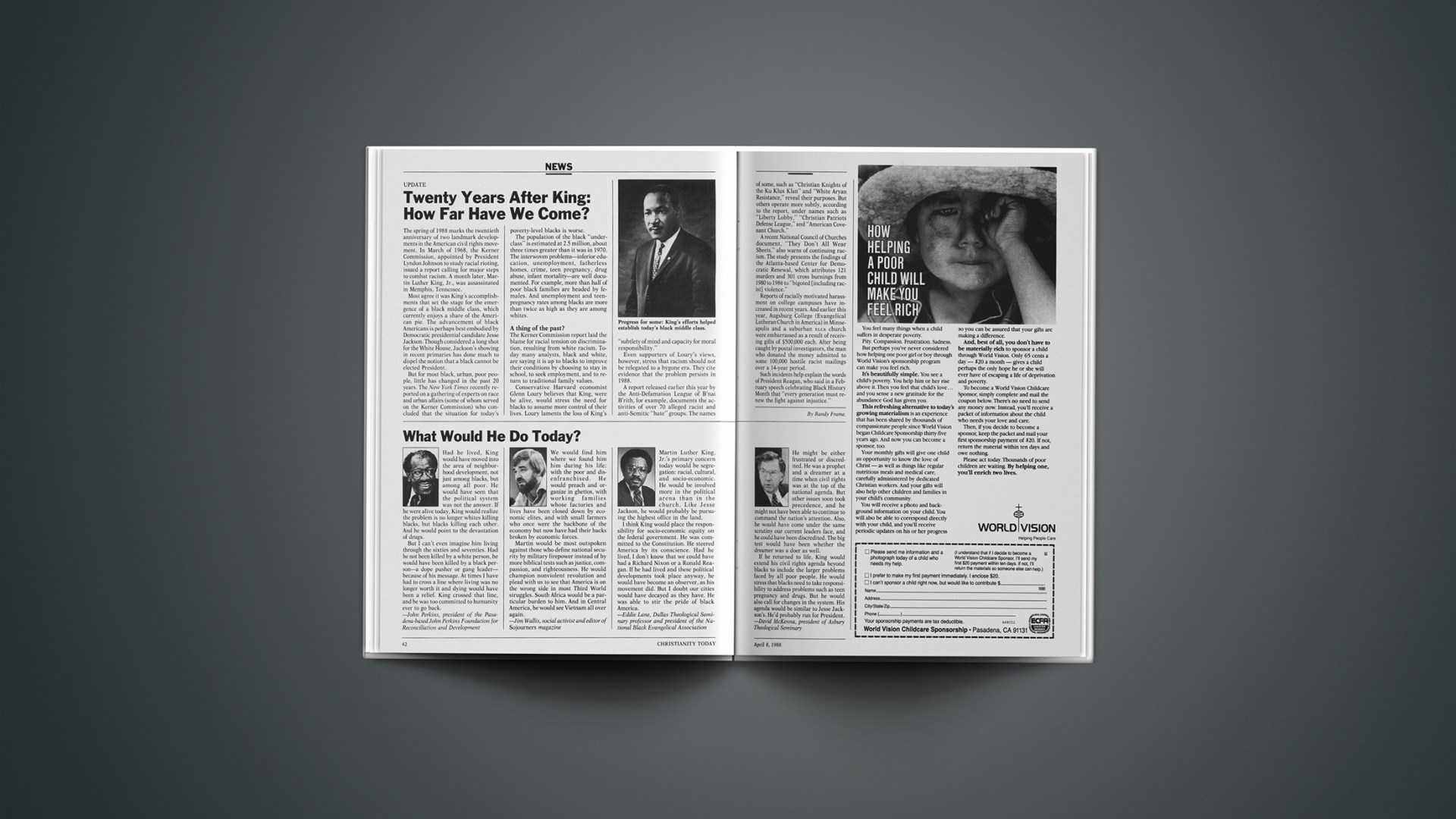

The spring of 1988 marks the twentieth anniversary of two landmark developments in the American civil rights movement. In March of 1968, the Kerner Commission, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson to study racial rioting, issued a report calling for major steps to combat racism. A month later, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee.

Most agree it was King’s accomplishments that set the stage for the emergence of a black middle class, which currently enjoys a share of the American pie. The advancement of black Americans is perhaps best embodied by Democratic presidential candidate Jesse Jackson. Though considered a long shot for the White House, Jackson’s showing in recent primaries has done much to dispel the notion that a black cannot be elected President.

But for most black, urban, poor people, little has changed in the past 20 years. The New York Times recently reported on a gathering of experts on race and urban affairs (some of whom served on the Kerner Commission) who concluded that the situation for today’s poverty-level blacks is worse.

The population of the black “underclass” is estimated at 2.5 million, about three times greater than it was in 1970. The interwoven problems—inferior education, unemployment, fatherless homes, crime, teen pregnancy, drug abuse, infant mortality—are well documented. For example, more than half of poor black families are headed by females. And unemployment and teen-pregnancy rates among blacks are more than twice as high as they are among whites.

A Thing Of The Past?

The Kerner Commission report laid the blame for racial tension on discrimination, resulting from white racism. Today many analysts, black and white, are saying it is up to blacks to improve their conditions by choosing to stay in school, to seek employment, and to return to traditional family values.

Conservative Harvard economist Glenn Loury believes that King, were he alive, would stress the need for blacks to assume more control of their lives. Loury laments the loss of King’s “subtlety of mind and capacity for moral responsibility.”

Even supporters of Loury’s views, however, stress that racism should not be relegated to a bygone era. They cite evidence that the problem persists in 1988.

A report released earlier this year by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, for example, documents the activities of over 70 alleged racist and anti-Semitic “hate” groups. The names of some, such as “Christian Knights of the Ku Klux Klan” and “White Aryan Resistance,” reveal their purposes. But others operate more subtly, according to the report, under names such as “Liberty Lobby,” “Christian Patriots Defense League,” and “American Covenant Church.”

A recent National Council of Churches document, “They Don’t All Wear Sheets,” also warns of continuing racism. The study presents the findings of the Atlanta-based Center for Democratic Renewal, which attributes 121 murders and 301 cross burnings from 1980 to 1986 to “bigoted [including racist] violence.”

Reports of racially motivated harassment on college campuses have increased in recent years. And earlier this year, Augsburg College (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) in Minneapolis and a suburban ELCA church were embarrassed as a result of receiving gifts of $500,000 each. After being caught by postal investigators, the man who donated the money admitted to some 100,000 hostile racist mailings over a 14-year period.

Such incidents help explain the words of President Reagan, who said in a February speech celebrating Black History Month that “every generation must renew the fight against injustice.”

By Randy Frame.

What Would He Do Today?

Had he lived, King would have moved into the area of neighborhood development, not just among blacks, but among all poor. He would have seen that the political system was not the answer. If he were alive today, King would realize the problem is no longer whites killing blacks, but blacks killing each other. And he would point to the devastation of drugs.

But I can’t even imagine him living through the sixties and seventies. Had he not been killed by a white person, he would have been killed by a black person—a dope pusher or gang leader—because of his message. At times I have had to cross a line where living was no longer worth it and dying would have been a relief. King crossed that line, and he was too committed to humanity ever to go back.

—John Perkins, president of the Pasadena-based John Perkins Foundation for Reconciliation and Development

We would find him where we found him him during his life: with the poor and disenfranchised. He would preach and organize in ghettos, with working families whose factories and lives have been closed down by economic elites, and with small farmers who once were the backbone of the economy but now have had their backs broken by economic forces.

Martin would be most outspoken against those who define national security by military firepower instead of by more biblical tests such as justice, compassion, and righteousness. He would champion nonviolent revolution and plead with us to see that America is on the wrong side in most Third World struggles. South Africa would be a particular burden to him. And in Central America, he would see Vietnam all over again.

—Jim Wallis, social activist and editor of Sojourners magazine

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s primary concern today would be segregation: racial, cultural, and socio-economic. He would be involved more in the political arena than in the church. Like Jesse Jackson, he would probably be pursuing the highest office in the land.

I think King would place the responsibility for socio-economic equity on the federal government. He was committed to the Constitution. He steered America by its conscience. Had he lived, I don’t know that we could have had a Richard Nixon or a Ronald Reagan. If he had lived and these political developments took place anyway, he would have become an observer, as his movement did. But I doubt our cities would have decayed as they have. He was able to stir the pride of black America.

—Eddie Lane, Dallas Theological Seminary professor and president of the National Black Evangelical Association

He might be either frustrated or discredited. He was a prophet and a dreamer at a time when civil rights was at the top of the national agenda. But other issues soon took precedence, and he might not have been able to continue to command the nation’s attention. Also, he would have come under the same scrutiny our current leaders face, and he could have been discredited. The big test would have been whether the dreamer was a doer as well.

If he returned to life, King would extend his civil rights agenda beyond blacks to include the larger problems faced by all poor people. He would stress that blacks need to take responsibility to address problems such as teen pregnancy and drugs. But he would also call for changes in the system. His agenda would be similar to Jesse Jackson’s. He’d probably run for President.

—David McKenna, president of Asbury Theological Seminary