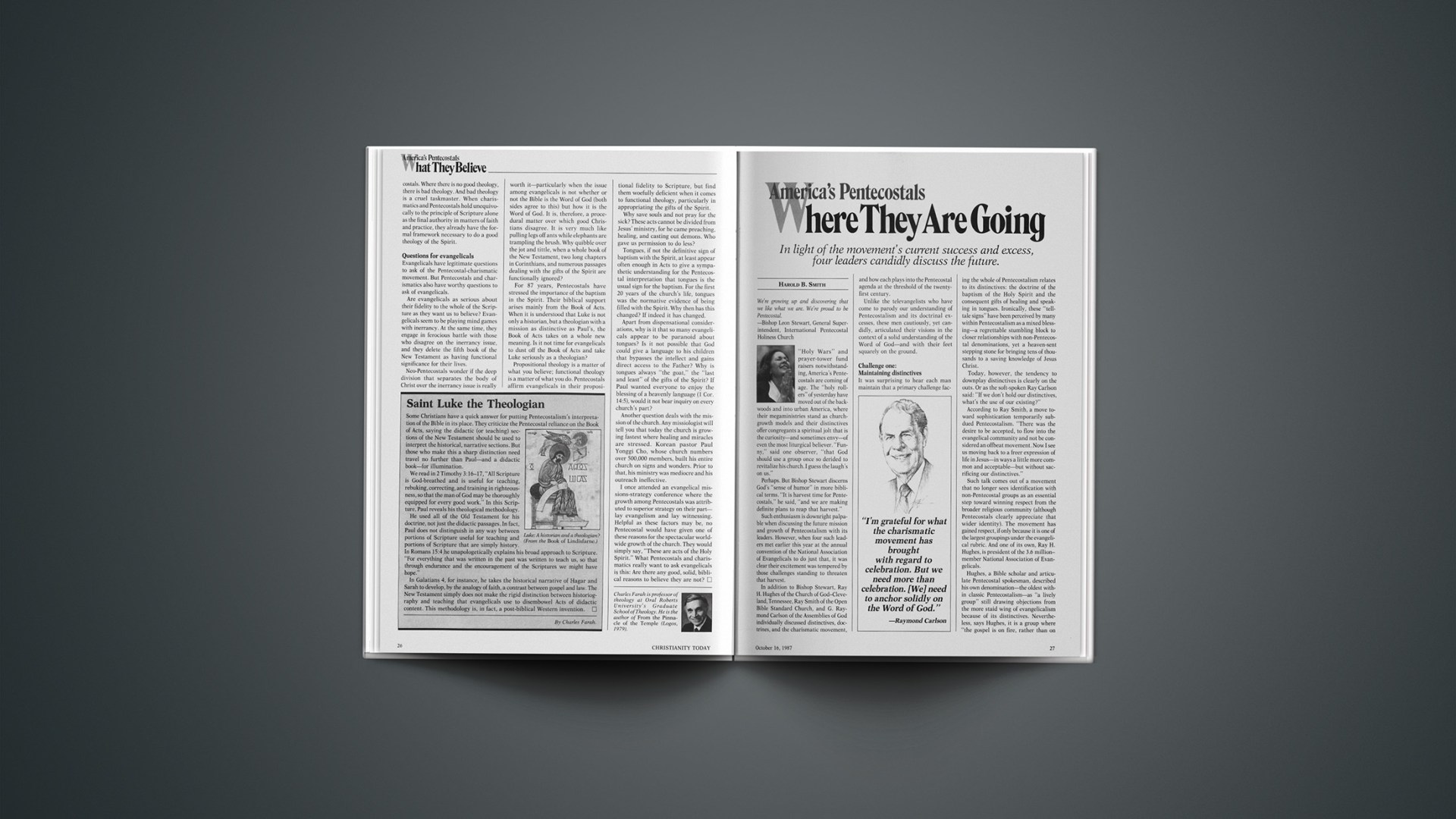

In light of the movement’s current success and excess, four leaders candidly discuss the future.

We’re growing up and discovering that we like what we are. We‘re proud to be Pentecostal.

—Bishop Leon Stewart, General Superintendent, International Pentecostal Holiness Church

“Holy Wars” and prayer-tower fund raisers notwithstanding, America’s Pentecostals are coming of age. The “holy rollers” of yesterday have moved out of the back-woods and into urban America, where their megaministries stand as church-growth models and their distinctives offer congregants a spiritual jolt that is the curiosity—and sometimes envy—of even the most liturgical believer. “Funny,” said one observer, “that God should use a group once so derided to revitalize his church. I guess the laugh’s on us.”

Perhaps. But Bishop Stewart discerns God’s “sense of humor” in more biblical terms. “It is harvest time for Pentecostals,” he said, “and we are making definite plans to reap that harvest.”

Such enthusiasm is downright palpable when discussing the future mission and growth of Pentecostalism with its leaders. However, when four such leaders met earlier this year at the annual convention of the National Association of Evangelicals to do just that, it was clear their excitement was tempered by those challenges standing to threaten that harvest.

In addition to Bishop Stewart, Ray H. Hughes of the Church of God-Cleve-land, Tennessee, Ray Smith of the Open Bible Standard Church, and G. Raymond Carlson of the Assemblies of God individually discussed distinctives, doctrines, and the charismatic movement, and how each plays into the Pentecostal agenda at the threshold of the twenty-first century.

Unlike the televangelists who have come to parody our understanding of Pentecostalism and its doctrinal excesses, these men cautiously, yet candidly, articulated their visions in the context of a solid understanding of the Word of God—and with their feet squarely on the ground.

Challenge One: Maintaining Distinctives

It was surprising to hear each man maintain that a primary challenge facing the whole of Pentecostalism relates to its distinctives: the doctrine of the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the consequent gifts of healing and speaking in tongues. Ironically, these “telltale signs” have been perceived by many within Pentecostalism as a mixed blessing—a regrettable stumbling block to closer relationships with non-Pentecostal denominations, yet a heaven-sent stepping stone for bringing tens of thousands to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ.

Today, however, the tendency to downplay distinctives is clearly on the outs. Or as the soft-spoken Ray Carlson said: “If we don’t hold our distinctives, what’s the use of our existing?”

According to Ray Smith, a move toward sophistication temporarily subdued Pentecostalism. “There was the desire to be accepted, to flow into the evangelical community and not be considered an offbeat movement. Now I see us moving back to a freer expression of life in Jesus—in ways a little more common and acceptable—but without sacrificing our distinctives.”

Such talk comes out of a movement that no longer sees identification with non-Pentecostal groups as an essential step toward winning respect from the broader religious community (although Pentecostals clearly appreciate that wider identity). The movement has gained respect, if only because it is one of the largest groupings under the evangelical rubric. And one of its own, Ray H. Hughes, is president of the 3.6 million-member National Association of Evangelicals.

Hughes, a Bible scholar and articulate Pentecostal spokesman, described his own denomination—the oldest within classic Pentecostalism—as “a lively group” still drawing objections from the more staid wing of evangelicalism because of its distinctives. Nevertheless, says Hughes, it is a group where “the gospel is on fire, rather than on ice.” The same could be said for the other three denominations as well.

“The emphasis on experience, on being built on the Holy Spirit, on being alive,” added Smith, “is like a love relationship where there’s emotion flowing and deep commitment, rather than a businesslike relationship solidly based on marriage principles alone. Pentecostalism adds the zip.”

And it is this characteristic “zip” that Pentecostals recognize as their peculiar kingdom contribution, and an attraction to more and more people. “The presentation of the real Jesus in our everyday lives and in our worship services,” said Bishop Stewart, “will attract a lot of people to our church.”

“It [the baptism of the Holy Spirit] is not our main doctrine,” cautioned Carlson. “That, of course, is Christ crucified, resurrected at the right hand of the Father. Still, it’s important to maintain the Pentecostal distinctives.”

“I think Pentecostals probably feel pretty comfortable with where they are,” said Smith. “It’s the non-Pentecostal evangelicals who are less and less comfortable—and they have to deal with that.”

Challenge Two: Charismatic Cordiality

Coming out of the closet with their distinctives will also necessitate Pentecostals coming to terms with a burgeoning charismatic movement. Surprisingly, surface similarities between classic Pentecostals and charismatics belie deep doctrinal differences. What looks to be a ready-made reservoir of new members for the historic Pentecostal churches is, in fact, a fiercely independent grouping within mainline Protestant and Catholic churches whose “freedom” earmarks both its worship style and doctrine. That troubles many Pentecostal leaders.

“I’m grateful for what the charismatic movement has brought with regard to celebration,” commented Carlson. “But it seems to be steeped in a very humanistic, materialistic kind of orientation. We need more than celebration. We always need that balance of the Word and the Spirit. You need to anchor solidly in the Word of God.”

Said Hughes: “We just do not endorse doctrines like positive confession—you know, name it/claim it, confess it/possess it. People are going to do that and be disappointed. But then again, I can hope those people go back to study the Scriptures concerning asking and having. They’ll see there are instructions, limitations. It says if he abides in you and if his words abide in you, and if it’s according to his will. From this closer inspection, and a desire to grow, they will come to the established Pentecostal churches. I am positive of that.”

Indeed, providing charismatics an anchor in one of the historic Pentecostal denominations is one way to minimize the “name it/claim it” aberrations.

“The independent movements,” continued Hughes, “are beginning to look for roots. They are looking for a solid place, a solid base—something they can sink their teeth into and raise their families in.”

Another “moderating influence,” yet one about which each man expressed certain reservations, is closer identification with the charismatic movement at events such as this past summer’s conference in New Orleans. Of the four groups represented, only the Pentecostal Holiness Church officially identified with the four-day affair drawing over 35,000 people.

“We will be an official part of it,” Bishop Stewart said before the conference, “but we are a little skeptical. But then, we were skeptical when joining the Pentecostal Fellowship of North America and the National Association of Evangelicals, and both of those experiences have proven to be good experiences for our church. In this particular case, we think the potential gain is worth the risk.”

Challenge Three: Dangling Doctrines

Interestingly, some of the doctrinal excesses of the charismatic movement have mirrored similar excesses within the historic Pentecostal churches and have consequently served to warn those churches against their own biblical infidelity. The age-old challenge to shore up emotionalism with a solid theological framework remains the quintessential nemesis facing Pentecostal leaders today.

“If you are living on experience only, you’re going to run aground,” Hughes said. “You must have an experience based in the Word, and not simply on whatever kind of theological framework you want.”

Clearly a concern of all the men was the materialistic prosperity gospel, trumpeted most noticeably by Pentecostal televangelists. Their comments concerning this “false witness” were particularly interesting in light of the fact that they were made prior to the PTL revelations.

“American churches have to get rid of hypocrisy, showmanship, sensationalism—a lot of that stuff,” said Bishop Stewart. “The young people today are smart enough to see right through that. What they want is the real Jesus.”

“It’s so easy to be caught up in ‘me-tooism’—what’s in it for me,” Carlson said. “We are not to use the Holy Spirit, the Holy Spirit is to use us. We must ask ourselves if what we are doing is just for us or for God’s glory. You can’t just name it and claim it.”

Explained Hughes: “Most of us Pentecostals came from the blue-collar working class, and the thing that made the movement grow was that it brought the gospel to the poor. We must not forget that, regardless of how the gospel has lifted us materially. We must not let materialism dominate us.”

“I like to put it this way,” Carlson added. “Stay in the middle of the streams of divine truth. Don’t be carried away by some of the spectacular. We can claim by faith, but the extremes—that’s what I want us to be careful of.”

In The End, Back To Basics

Carlson’s “middle of the stream” analogy summarized the general direction each of the four men hopes to steer his respective denomination in the days ahead. While seeing their Pentecostalism as unique, they all revel in that uniqueness only as it clearly focuses on a biblical understanding of man’s sinfulness, God’s love and forgiveness, and life in Christ.

“We have a threefold goal,” Carlson said. “First, that there would be a renewal of a sense of the holiness and the majesty of God. There’s an intimacy we can experience. We should draw near to him in prayer. He’s not far off.

“Second,” Carlson continued, “I pray that God would give our people a burning passion for the lost. And finally, I ask that God would give us a sense of discipleship with the spirit of servant-hood.”

Such an agenda, of course, sounds like standard religious fare. But in the context of this burgeoning movement, the talk is hardly hollow. The flush of “success” is still very much on these men, and with it an optimism that regards all challenges as challenges that will be met: this comes, even when aspects of that success turn periodically to embarrassment. Thus, an exuberant Ray Smith could triumphantly exclaim that Pentecostals have a sense of destiny “because Pentecostalism is biblical.”