HIAWATHA BRAY1Hiawatha Bray is a free-lance writer living in Chicago. A graduate of Wheaton Graduate School, he has written for Christianity Today, Essence, and Computerpeople Monthly.

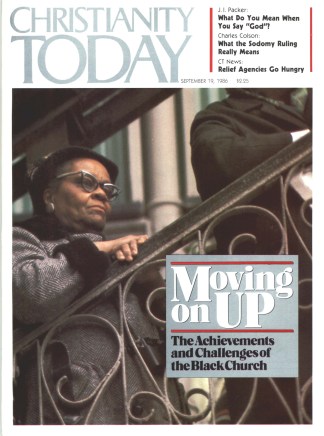

There is no “black church”; there are only black churches: thousands of them, ranging from great African Methodist Episcopal congregations, to tiny storefront gatherings of Pentecostals.

And yet, there is a “black church,” for a common tradition of shared culture and shared oppression binds together all black congregations, distinguishing them from their white counterparts. There is a unique style of black worship, and political concerns that are unique to black pastors and congregants. So important is the black church to black society that you cannot make sense of one without understanding the other.

Segregated Christianity

Ebony magazine estimated in 1984 that there are 18 to 20 million nominal black Christians in the United States, of whom approximately one-fourth are regular churchgoers. Of America’s professing black Christians, about 80 percent belong to denominations founded and controlled by blacks. Despite all the societal efforts made to ensure that whites and blacks work and study together, the races continue to worship in segregation.

Perhaps it could not have been otherwise. The same Europeans who introduced Africans to the gospel shackled them in slave ships for the grim voyage to the Americas. They never meant to worship God on an equal footing with their slaves.

The founding of the first great black denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), was a response among free blacks to the bigotry of white Christians. It was the time of the Second Great Awakening, and fervent preachers, mainly Methodists and Baptists, challenged the religious indifference that existed after the Revolution. The new religious passion affected blacks, both slave and free. In free states, growing numbers of blacks sought spiritual communion in Baptist and Methodist congregations. But the white Christians in them would not allow it.

In 1787 Richard Allen was forcibly prevented from praying with white worshipers at Saint George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Shortly thereafter, he founded the Free African Society. Society members at first maintained fellowship with whites, where allowed, but eventually began to hold their own religious services. In 1794 a minority of the society, under Allen’s leadership, founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The AME church was more than a place for blacks to worship in dignity. It was an expression of the bedrock principle of black theology. Blacks knew that white racism was more than earthly injustice; it was sin, as deep and grave as idolatry. “It is theologically significant that since the AME church was founded, it has never practiced institutional racism,” says Gregory Ingram, pastor of the Quinn Chapel AME Church in Chicago. “Our doors have always been open for those who want to worship God freely. Part of our creedal statement is ‘God our Father; Christ our Redeemer; Man our Brother.’ ”

Black churches are more than a refuge for oppressed Christians. Their existence is a positive affirmation of Christian truths white Americans often forget.

The Spiritual Lives Of Slaves

Understanding the black church, present and past, requires some knowledge of the spiritual lives of its original members.

Few slaves had become Christians by the 1800s (almost no one had preached the gospel to them). This began to change as evangelists persuaded slaveholders that a Christian slave was a better slave. At first the evangelists were often staunch abolitionists. But to gain permission to preach to slaves, they were forced to modify their position. In time, much of the Southern clergy became the staunch defenders of slavery. The Methodists, for example, created a new catechism for slaves. “What did God make you for?” the catechism asked. Answered the good slave, “To make a crop.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of slaves had become believers. But in 1822 it was discovered that Denmark Vesey, a black sailor, had planned to lead a slave revolt with the aid of leading black Methodists. Nine years later the slave preacher Nat Turner led a bloody revolt. These and other incidents eventually led whites to apply strict controls on religious activity among slaves.

It was no use, however. Throughout the South, Christian faith and political freedom had become linked in the minds of blacks. Slaves gathered at night for secret religious services where the white gospel was taught and prayers offered to a God who wanted them free.

Thus, from the beginning, black people have associated Christianity with social and political freedom as well as spiritual salvation. They have not been as prone as white American Christians to speak of the faith in dichotomies such as soul versus body and political versus spiritual. This tradition was reinforced in the aftermath of slavery because of the unique position of the church in the black community.

“The black church antedates the black community. Until the black church there was no black community,” says C. Eric Lincoln, professor of religion and culture at Duke University. With their African traditions denied them, and with social and political interaction strictly controlled even after emancipation, the church was for decades the only strong black institution in America.

After the brief political freedoms of the Reconstruction period, black participation in politics was almost totally eliminated. As a result, says Professor Lincoln, “The church, being the only institution blacks had that was reasonably impervious to white control, obviously became the place where black secular politics would also have its nurture. There was nowhere else for a political consciousness to develop.”

Pastor Maceo Woods of Chicago’s Christian Tabernacle Church thinks spiritual and political concerns are both vital to the mission of the church. “I feel the church is the hub of political aspirations.” But politics, he warns, “should not become the text of the morning. The Word of God should take pre-eminence. Our political actions should come out of the Word of God.”

The political consciousness of black Christians is often very different from that of their white brethren. David Edwin Harrell, Jr., in his book White Sects and Black Men, referred to fundamentalist groups when he wrote, “Sectarian preachers have frequently been among the most vocal supporters of segregation in the South since World War II.”

The Battle For Survival

Most conservative Christians now categorically condemn racism. But there remain significant differences between the white and black understanding of politics and faith. White evangelicals and fundamentalists, in their denunciations of liberalism and secular humanism, tend to take a negative view of the state. In the rhetoric of the New Right, the federal government (except for military power) has become an enemy of freedom (too much power). Government social programs are wasteful and encourage sloth and dishonesty. And liberal court decisions undermine the true meaning of the Constitution.

There may be some truth in these claims. But for blacks, the power of the federal government has allowed them to get decent jobs and send their children to decent schools. With millions of blacks in poverty, social programs are often the difference between life and death. And the Supreme Court, by striking down discriminatory laws, has made the Constitution a living document for blacks.

But many black Christians, while rejecting the political conservatism whites often embrace, do share the theological conservatism of white evangelicals. Edward Freeman, a leader in the National Baptist Convention (America’s third-largest Protestant denomination), stated that black Baptists differ with Jerry Falwell politically, but agree on such doctrinal matters as “belief in God, the Holy Spirit, the deity of Jesus Christ, the fall of man, the doctrine of sin, salvation, redemption, et cetera.”

In 1963, black churchmen formed the National Black Evangelical Association to deal with the special concerns of black evangelicals. Executive director Aaron Hamlin says the organization is still necessary. “There are still needs that are not being addressed by the white evangelical community, in relation to jobs, poverty programs, and the racism that still exists.”

Christian political activism grows out of the social condition of the community, conditions very different from those faced by whites. Pastor Ingram says, “The AME church grew out of a sense of protest, so we were closely involved with the survival issues of our people.” Survival for blacks does not mean a battle against an abstract secular humanism. It means a battle for voting rights, jobs, better housing.

The Style Of Worship

A positive factor that separates black and white Christians is the difference in worship styles. For one thing, black worship demands emotional as well as intellectual agreement with religious truth. Some have supposed that the preaching in black churches has little intellectual content. But to many black Christians, an understanding of the gospel should mean more than mere intellectual assent. It should be an intensification of the white evangelical tradition—demanding heartfelt faith in the truths of the gospel.

Larry Murphy directs the Institute for Black Religious Research at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. “The commonalities in black worship,” says Murphy, “have to do with the very strong focus on an expressiveness which picks up on the evangelical Protestant tradition of experiential piety, and you find that running fairly commonly throughout black churches.”

Another common theme is the crucial importance of the pastor and his preaching in black churches. Says Clay Evans, pastor of Chicago’s Fellowship Baptist Church and chairman emeritus of Operation PUSH, “The power comes from the pulpit down, as it did with the prophets of old. In most black churches, the power remains in the pulpit. Pastors lead the congregation, the congregation doesn’t lead them.”

And the pastor leads by preaching. This preaching—emotional, biblical, and prophetic—is at the core of black worship. It is no accident that most of the greatest black leaders have been preachers. From Nat Turner to Martin Luther King, black Christian preaching has always stood for social as well as religious leadership.

Will The Churches Integrate?

Only a minority of white or black Christians worship in integrated churches. Could this change? Pastor Woods thinks there have been superficial improvements: “I feel there has certainly been an attempt to break down the barriers, but it’s just external. There’s got to be an internal change.” C. Eric Lincoln says, “The thing that would most likely make it change would be a different view of black people on the part of white people. I lay the problem frankly at the door of white Christianity, and I think that white Christianity will have to rethink its perspectives about people if we are going to have anything that approaches a common Christian front.”

But, Lincoln adds, many black Christians are no longer interested in church integration. “As we went through the sixties and the seventies we saw less and less reason to believe that the white church had brotherhood on its mind. So, in my opinion, it will be increasingly difficult to persuade blacks that they ought to be particularly concerned about the white church.”

But contempt for white racism is only part of the story. In the last two decades, blacks discovered a new sense of pride and self-respect. To Larry Murphy of Garrett-Evangelical Seminary, the black church tradition has a special strength born of the historical agonies and victories of African-Americans. It speaks to him as no other religious tradition can. “I don’t attend a white church, although I work in a white community. But I find my greatest level of comfort in a church that reflects my own traditions, my own biological identity. I see that as nothing negative.”

But for Christians, the final issue must be whether our traditions and practices are pleasing to God. Does the Lord who calls the church his body intend that its various limbs be separate from one another? Perhaps for a time. Perhaps the racial division of the American church is a peculiar message from God to his people. Willie White, a black Baptist preacher, described it in the Christian Century: “It is precisely God’s purpose that stands opposed to any thoroughgoing ecumenical approach between the black and white churches of America.… [T]he black church is the instrument of God in this world, not just a group [of people] who are separated unto themselves.… [T]he black church is the instrument of God in this world, not just a group [of people] who are separated unto themselves until the good graces of white [people] call them back into fellowship.… [T]he establishment of the black church was not the work of a mere man; it was the work of Christ.”