Once when the young G. K. Chesterton was courting Frances Blogg, her mother “politely asked his opinion of her new wallpaper.” “Chesterton got up to take a closer look,” reports biographer Alzina Stone Dale, “then absent-mindedly took a piece of chalk from his pocket and drew a picture of Frances on the wall.”

The quotable author of Orthodoxy and the Father Brown mysteries is generally known as “a jolly journalist,” the man who loved to debate the likes of Clarence Darrow and George Bernard Shaw, and a believer who valiantly took up the pen to fight growing modernism in the English church. But he was also an artist to the core—incessantly drawing, cartooning and doodling on any available surface. He always carried chalk, he covered the margins of his manuscripts with sketches, and (unfortunately) could not stand the sight of a blank wall.

Now, on the fiftieth anniversary of Chesterton’s death, Loyola University Press has published The Art of G. K. Chesterton, a handsomely designed volume with text by Alzina Stone Dale. The book includes recently acquired chalk drawings purchased at a Sotheby’s auction by Loyola and donated to Wheaton College’s Wade Collection where Chesterton archives were already in existence. The book’s only disappointing feature is the omission of captions and a list of plates to help the reader identify the drawings.

Dale traces the development of Chesterton’s drawing from his earliest memories of his father’s cardboard puppets and toy theater through his training at the Slade School of Art to his satirical cover drawings for GK’s Weekly. And she sketches the way in which he relied on art for analogy. Take this passage from Orthodoxy: “Art is limitation; the essence of every picture is the frame. If you draw a giraffe, you must draw him with a long neck. If, in your bold creative way you … draw him with a short neck, you … will find you are not free to draw a giraffe.”

While in his formal art training, Chesterton resisted the then popular notion of art for art’s sake, maintaining that the greatest artists had always been didactic. “Art, like morality,” he said, “consists in drawing the line somewhere.”

“In both word and pictures,” writes Dale, “he made his point with a strong, firm line that outlined a central figure (or idea) against an impressionistic, often fantastic, background. His verbal penchant for pushing an argument to absurdity was the literary counterpart of the visual effect he created by cartooning his message. In both mediums, by using artificial limits like the frame of the toy theatre, he gave focus and clarity to his ideas. In this way Chesterton was able to draw the moral so starkly or whimsically that its point cannot be missed by anyone.”

DAVID NEFF

When a catastrophic famine in the Soviet Ukraine claimed seven million lives in the thirties, almost half of them children, no one wanted to hear about it.

“When stories about the famine first came out, they were so incredible, people didn’t believe them,” said Slavko Nowytski, director of a recent documentary on the disaster, following its screening at the New York Film Festival. “There was a depression here. People wanted to hear something positive.” So the truth was suppressed.

Even the Moscow correspondent for the New York Times, Walter Duranty, covered up the tragedy, writing glowing reports of conditions in the Ukraine after a junket through the region sanctioned by Stalin.

Now Nowytski’s film, Harvest of Despair, exposes the terrible truth behind the Ukrainian famine of 1932–33. Produced for the Ukrainian Famine Research Committee in Canada, the 55-minute documentary claims that Stalin deliberately starved the Ukraine by seizing and exporting all its grain to pay for his industrialization program. An underlying objective, the film contends, was to whip into submission the nationalistic Ukrainians, who resisted the swallowing up of their homeland into the USSR.

The film is decidedly one-sided, and that detracts from its credibility. Failure to include representatives of the official Soviet view—which maintains the famine never occurred—leaves the documentary open to charges of bias.

Yet interviews with such credible sources as Malcolm Muggeridge—a journalist in the Soviet Union at the time—and the emotional testimonies of famine survivors now in the West present a compelling case. Says Muggeridge: “It was done with deliberateness and a total absence of any kind of sympathy.” He defied a travel ban on foreign correspondents to report on the famine and then sent his dispatches out of the country in a diplomatic bag.

Though the stark images shot in the Ukraine during the thirties help remove the tragedy from a distant time and place, the inevitable question arises: Why tell about it now, 50 years later?

The answer, according to Nowytski, is because much of the evidence is just now coming to light. “The stories weren’t told at first by the people who lived them because they were too traumatic.” (The director’s own family left the Ukraine when he was four.) When eyewitnesses started speaking up and documents corroborating their recollections were recently declassified, the time was ripe to tell the truth, he said.

To tell the truth, to expose dark deeds to the light—indeed a biblical injunction—is an important function of the documentary. Harvest of Despair exposes the evil of Stalinism. It graphically depicts the tragedy so that no one will forget, so that no one can deny it happened. It did happen. And it still matters.

BUD BULTMAN1Bud Bultman is a graduate student at Columbia University specializing in Eastern Europe and a upi intern at the United Nations.

“Praise the Lord with loud shouts …” “… timbrel and dance.”

When was the last time you shouted—or danced—in church?

I recently surveyed a number of Chicago-area churches that respond to the psalmist’s invitation and incorporate dance into Christian worship. Their reasons are as varied as the churches, but there is a common desire: to enrich the quality of their worship.

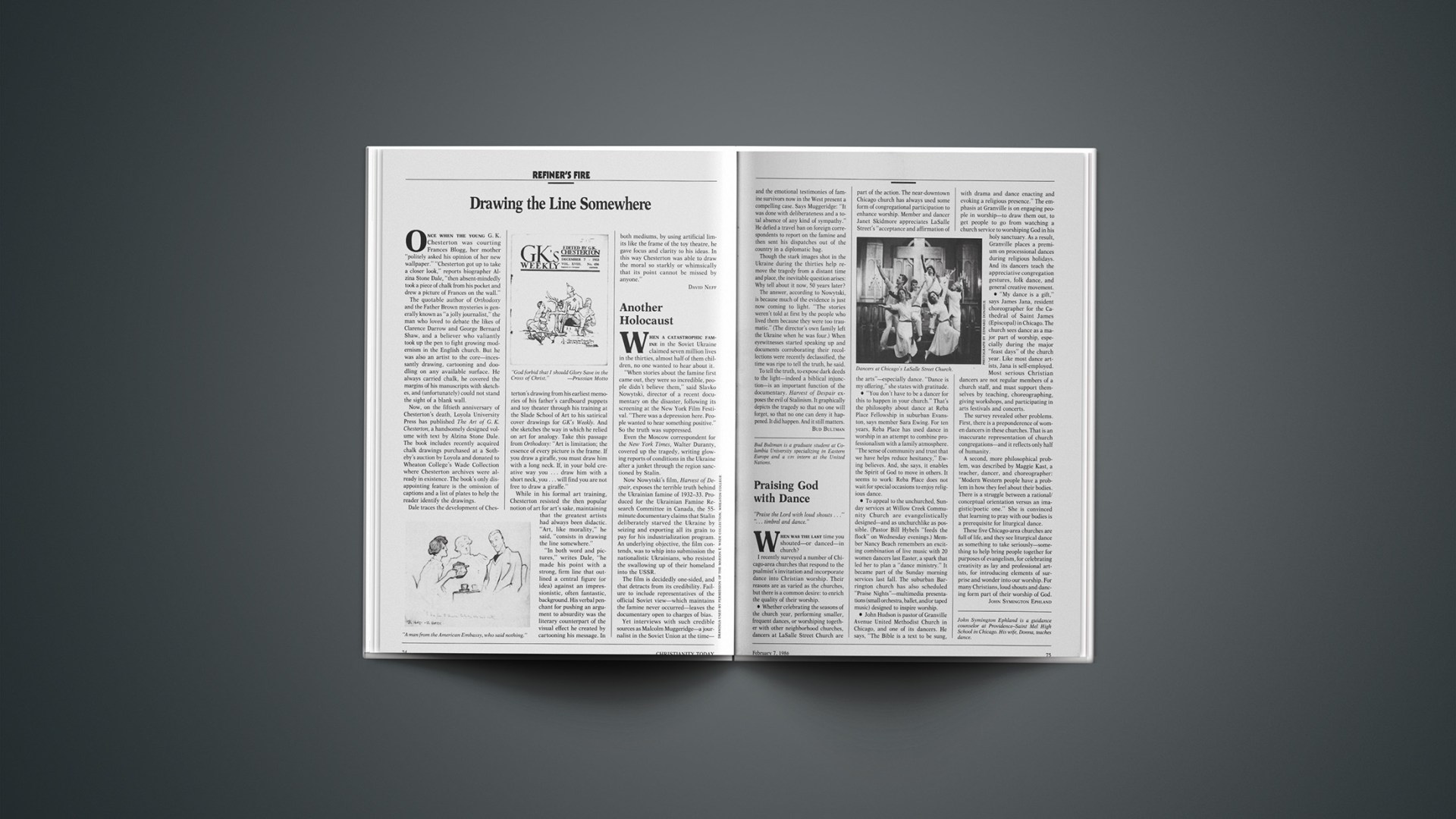

• Whether celebrating the seasons of the church year, performing smaller, frequent dances, or worshiping together with other neighborhood churches, dancers at LaSalle Street Church are part of the action. The near-downtown Chicago church has always used some form of congregational participation to enhance worship. Member and dancer Janet Skidmore appreciates LaSalle Street’s “acceptance and affirmation of the arts”—especially dance. “Dance is my offering,” she states with gratitude.

• “You don’t have to be a dancer for this to happen in your church.” That’s the philosophy about dance at Reba Place Fellowship in suburban Evanston, says member Sara Ewing. For ten years, Reba Place has used dance in worship in an attempt to combine professionalism with a family atmosphere. “The sense of community and trust that we have helps reduce hesitancy,” Ewing believes. And, she says, it enables the Spirit of God to move in others. It seems to work: Reba Place does not wait for special occasions to enjoy religious dance.

• To appeal to the unchurched, Sunday services at Willow Creek Community Church are evangelistically designed—and as unchurchlike as possible. (Pastor Bill Hybels “feeds the flock” on Wednesday evenings.) Member Nancy Beach remembers an exciting combination of live music with 20 women dancers last Easter, a spark that led her to plan a “dance ministry.” It became part of the Sunday morning services last fall. The suburban Barrington church has also scheduled “Praise Nights”—multimedia presentations (small orchestra, ballet, and/or taped music) designed to inspire worship.

• John Hudson is pastor of Granville Avenue United Methodist Church in Chicago, and one of its dancers. He says, “The Bible is a text to be sung, with drama and dance enacting and evoking a religious presence.” The emphasis at Granville is on engaging people in worship—to draw them out, to get people to go from watching a church service to worshiping God in his holy sanctuary. As a result, Granville places a premium on processional dances during religious holidays. And its dancers teach the appreciative congregation gestures, folk dance, and general creative movement.

• “My dance is a gift,” says James Jana, resident choreographer for the Cathedral of Saint James (Episcopal) in Chicago. The church sees dance as a major part of worship, especially during the major “feast days” of the church year. Like most dance artists, Jana is self-employed. Most serious Christian dancers are not regular members of a church staff, and must support themselves by teaching, choreographing, giving workshops, and participating in arts festivals and concerts.

The survey revealed other problems. First, there is a preponderence of women dancers in these churches. That is an inaccurate representation of church congregations—and it reflects only half of humanity.

A second, more philosophical problem, was described by Maggie Kast, a teacher, dancer, and choreographer: “Modern Western people have a problem in how they feel about their bodies. There is a struggle between a rational/conceptual orientation versus an imagistic/poetic one.” She is convinced that learning to pray with our bodies is a prerequisite for liturgical dance.

These five Chicago-area churches are full of life, and they see liturgical dance as something to take seriously—something to help bring people together for purposes of evangelism, for celebrating creativity as lay and professional artists, for introducing elements of surprise and wonder into our worship. For many Christians, loud shouts and dancing form part of their worship of God.

JOHN SYMINGTON EPHLAND2John Symington Ephland is a guidance counselor at Providence—Saint Mel High School in Chicago. His wife, Donna, teaches dance.