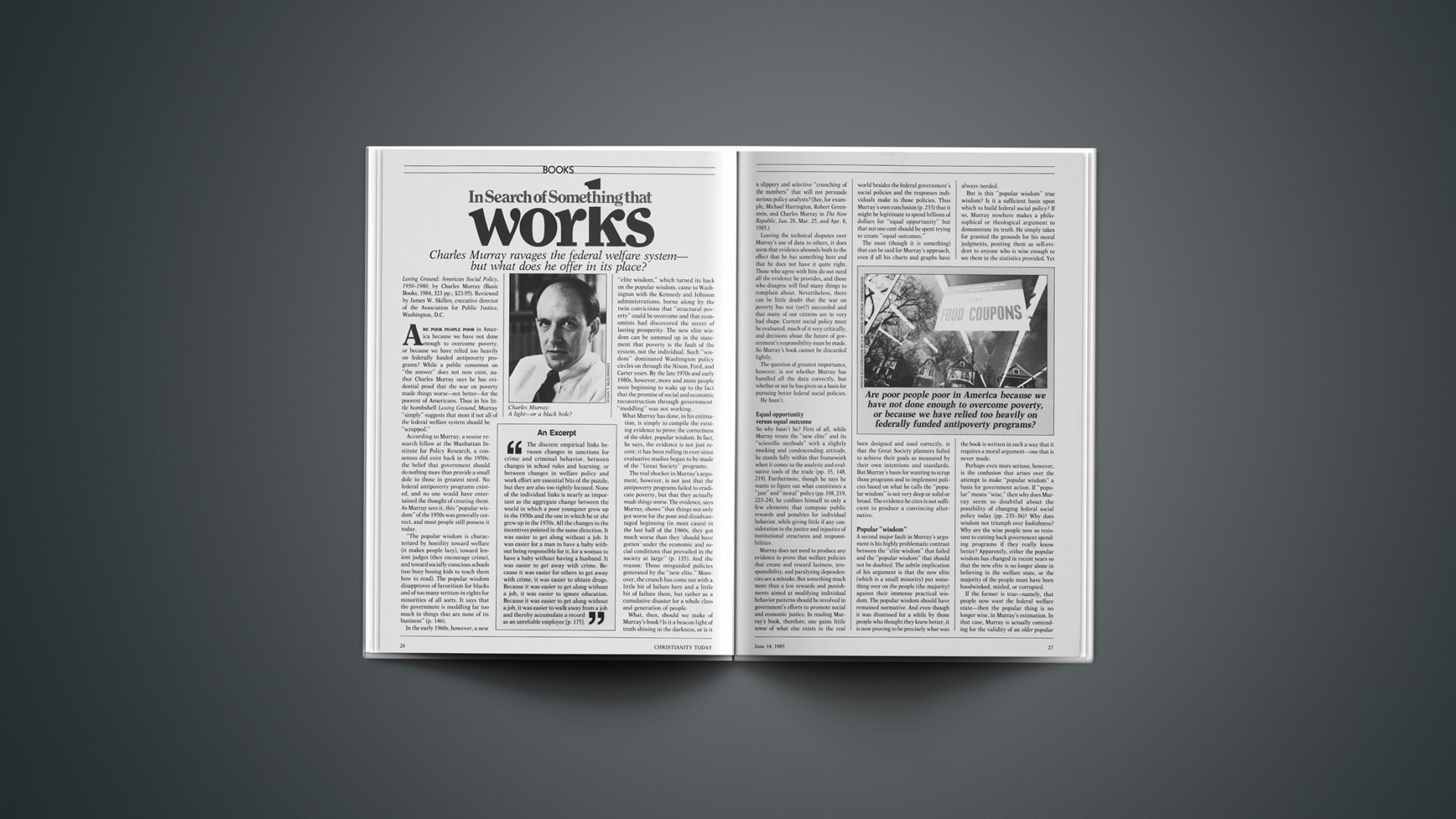

Charles Murray ravages the federal welfare system—but what does he offer in its place?

Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980, by Charles Murray (Basic Books, 1984, 323 pp.; $23.95). Reviewed by James W. Skillen, executive director of the Association for Public Justice, Washington, D.C.

Are poor people poor in America because we have not done enough to overcome poverty, or because we have relied too heavily on federally funded antipoverty programs? While a public consensus on “the answer” does not now exist, author Charles Murray says he has evidential proof that the war on poverty made things worse—not better—for the poorest of Americans. Thus in his little bombshell Losing Ground, Murray “simply” suggests that most if not all of the federal welfare system should be “scrapped.”

According to Murray, a senior research fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, a consensus did exist back in the 1950s: the belief that government should do nothing more than provide a small dole to those in greatest need. No federal antipoverty programs existed, and no one would have entertained the thought of creating them. As Murray sees it, this “popular wisdom” of the 1950s was generally correct, and most people still possess it today.

“The popular wisdom is characterized by hostility toward welfare (it makes people lazy), toward lenient judges (they encourage crime), and toward socially conscious schools (too busy busing kids to teach them how to read). The popular wisdom disapproves of favoritism for blacks and of too many written-in rights for minorities of all sorts. It says that the government is meddling far too much in things that are none of its business” (p. 146).

In the early 1960s, however, a new “elite wisdom,” which turned its back on the popular wisdom, came to Washington with the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, borne along by the twin convictions that “structural poverty” could be overcome and that economists had discovered the secret of lasting prosperity. The new elite wisdom can be summed up in the statement that poverty is the fault of the system, not the individual. Such “wisdom” dominated Washington policy circles on through the Nixon, Ford, and Carter years. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, more and more people were beginning to wake up to the fact that the promise of social and economic reconstruction through government “meddling” was not working.

An Excerpt

“The discrete empirical links between changes in sanctions for crime and criminal behavior, between changes in school rules and learning, or between changes in welfare policy and work effort are essential bits of the puzzle, but they are also too tightly focused. None of the individual links is nearly as important as the aggregate change between the world in which a poor youngster grew up in the 1950s and the one in which he or she grew up in the 1970s. All the changes in the incentives pointed in the same direction. It was easier to get along without a job. It was easier for a man to have a baby without being responsible for it, for a woman to have a baby without having a husband. It was easier to get away with crime. Because it was easier for others to get away with crime, it was easier to obtain drugs. Because it was easier to get along without a job, it was easier to ignore education. Because it was easier to get along without a job, it was easier to walk away from a job and thereby accumulate a record as an unreliable employee [p. 175].”

What Murray has done, in his estimation, is simply to compile the existing evidence to prove the correctness of the older, popular wisdom. In fact, he says, the evidence is not just recent; it has been rolling in ever since evaluative studies began to be made of the “Great Society” programs.

The real shocker in Murray’s argument, however, is not just that the antipoverty programs failed to eradicate poverty, but that they actually made things worse. The evidence, says Murray, shows “that things not only got worse for the poor and disadvantaged beginning (in most cases) in the last half of the 1960s, they got much worse than they ‘should have gotten’ under the economic and social conditions that prevailed in the society at large” (p. 135). And the reason: Those misguided policies generated by the “new elite.” Moreover, the crunch has come not with a little bit of failure here and a little bit of failure there, but rather as a cumulative disaster for a whole class and generation of people.

What, then, should we make of Murray’s book? Is it a beacon light of truth shining in the darkness, or is it a slippery and selective “crunching of the numbers” that will not persuade serious policy analysts? (See, for example, Michael Harrington, Robert Greenstein, and Charles Murray in The New Republic, Jan. 28, Mar. 25, and Apr. 8, 1985.)

Leaving the technical disputes over Murray’s use of data to others, it does seem that evidence abounds both to the effect that he has something here and that he does not have it quite right. Those who agree with him do not need all the evidence he provides, and those who disagree will find many things to complain about. Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that the war on poverty has not (yet?) succeeded and that many of our citizens are in very bad shape. Current social policy must be evaluated, much of it very critically, and decisions about the future of government’s responsibility must be made. So Murray’s book cannot be discarded lightly.

The question of greatest importance, however, is not whether Murray has handled all the data correctly, but whether or not he has given us a basis for pursuing better federal social policies.

He hasn’t.

Equal Opportunity Versus Equal Outcome

So why hasn’t he? First of all, while Murray treats the “new elite” and its “scientific methods” with a slightly mocking and condescending attitude, he stands fully within that framework when it comes to the analytic and evaluative tools of the trade (pp. 35, 148, 219). Furthermore, though he says he wants to figure out what constitutes a “just” and “moral” policy (pp. 198, 219, 223–24), he confines himself to only a few elements that compose public rewards and penalties for individual behavior, while giving little if any consideration to the justice and injustice of institutional structures and responsibilities.

Murray does not need to produce any evidence to prove that welfare policies that create and reward laziness, irresponsibility, and paralyzing dependencies are a mistake. But something much more than a few rewards and punishments aimed at modifying individual behavior patterns should be involved in government’s efforts to promote social and economic justice. In reading Murray’s book, therefore, one gains little sense of what else exists in the real world besides the federal government’s social policies and the responses individuals make to those policies. Thus Murray’s own conclusion (p. 233) that it might be legitimate to spend billions of dollars for “equal opportunity” but that not one cent should be spent trying to create “equal outcomes.”

The most (though it is something) that can be said for Murray’s approach, even if all his charts and graphs have been designed and used correctly, is that the Great Society planners failed to achieve their goals as measured by their own intentions and standards. But Murray’s basis for wanting to scrap those programs and to implement policies based on what he calls the “popular wisdom” is not very deep or solid or broad. The evidence he cites is not sufficient to produce a convincing alternative.

Popular “Wisdom”

A second major fault in Murray’s argument is his highly problematic contrast between the “elite wisdom” that failed and the “popular wisdom” that should not be doubted. The subtle implication of his argument is that the new elite (which is a small minority) put something over on the people (the majority) against their immense practical wisdom. The popular wisdom should have remained normative. And even though it was dismissed for a while by those people who thought they knew better, it is now proving to be precisely what was always needed.

But is this “popular wisdom” true wisdom? Is it a sufficient basis upon which to build federal social policy? If so, Murray nowhere makes a philosophical or theological argument to demonstrate its truth. He simply takes for granted the grounds for his moral judgments, positing them as self-evident to anyone who is wise enough to see them in the statistics provided. Yet the book is written in such a way that it requires a moral argument—one that is never made.

Perhaps even more serious, however, is the confusion that arises over the attempt to make “popular wisdom” a basis for government action. If “popular” means “wise,” then why does Murray seem so doubtful about the possibility of changing federal social policy today (pp. 235–36)? Why does wisdom not triumph over foolishness? Why are the wise people now so resistant to cutting back government spending programs if they really know better? Apparently, either the popular wisdom has changed in recent years so that the new elite is no longer alone in believing in the welfare state, or the majority of the people must have been hoodwinked, misled, or corrupted.

If the former is true—namely, that people now want the federal welfare state—then the popular thing is no longer wise, in Murray’s estimation. In that case, Murray is actually contending for the validity of an older popular wisdom that is no longer so popular. He would, therefore, be campaigning for the right of a new elite (people like himself) to displace the older “new elite” in the circles of federal policy making.

But why should one elite have any more right to make policy than another elite? If Murray’s judgments and approach are correct, then this is not because wisdom is popular (though it might be), but rather because it is right. And since the “rightness” or “correctness” of a particular brand of wisdom has not been demonstrated here, we are left with nothing more than one elite criticizing another elite by using statistics.

If the assumptions about human behavior held by social policy makers are incorrect assumptions, then what we need (and what Christians should be calling for and helping to provide) is a principled argument for the proper role of government in dealing with poverty and oppression, and a political philosophy grounded in a well-developed biblical view of justice.

Losing Ground: No

Charles Murray’s Losing Ground is acclaimed as an empirical study that finally proves that public assistance is not only useless, but harmful to those it is supposed to help. In fact, the empirical aspects of the study are its weakest points. Most important, Murray usually uses the entire black population to represent all impoverished Americans. In reality, less than one-third of the black population is on welfare; nearly seven of every ten people on welfare are white. But the reader looks in vain for data on the poor white group.

In addition, Murray shows that the real purchasing power of those on public assistance increased substantially after 1965. He infers this should have reduced the number of people below the poverty line. But he omits the fact that the rest of society was gaining real purchasing power at the same time. Thus the relative position of the poor in society improved much less than their absolute purchasing power, and economists have long recognized that relative income and consumption play a crucial role in a person’s economic behavior. The motivation to escape poverty is diminished if one’s best efforts to move up the economic ladder are stymied by the advance of everyone else higher up the ladder.

Finally, Murray’s interpretation of the data is marred because he ignores the dramatic social changes affecting young and low-income blacks during the 1960s and 1970s. His data studies are inconclusive at best, and possibly very misleading.

I see the book as an effort to substantiate a world view that includes three principles: Individual autonomy is the highest goal; free markets are as much a part of natural law and creation as, say, gravity, and therefore are not subject to moral analysis any more than the law of gravity; and any collective intervention into these “laws of nature” is counterproductive and inevitably limits freedom.

For Murray, then, it is an a priori belief that a welfare system is unhelpful and probably harmful. For all the numbers in his book, the issue for Murray is not really empirical.

There is an alternative world view that I would argue is more thoroughly biblical. To summarize it in three points: God is glorified in the context of the church, a community, which may mean that individual autonomy must at times be sacrificed; markets are the most efficient allocators of resources, but they should not operate (and do not, in fact) independently of a society’s cultural, legal, and religious values; land, since collective action is inevitable in any system, it is the responsibility of Christians to influence public policy for the good wherever possible.

It is true that good intentions are not sufficient and that guilt is not a desirable motivator. Any welfare program must foster responsibility in recipients and create incentive. It is incumbent on Christians to model care for the unfortunate and to propose better welfare policies. (One example would be the rewarding of administrators for every poor person that is helped off the welfare rolls. Currently the administrative rewards go to those with larger client lists.)

Eliminating all welfare, as Murray suggests, could lead to the higher poverty levels of the pre-1950s, when welfare expenditures were nominal. Indeed, answers are evasive, and all too few Christians have been working at finding them. Perhaps this controversial book, despite its shortcomings, will change that sad fact.

By Jim Halteman, associate professor of economics at Wheaton (Ill.) College.

The Buck Stops Where?

The third and final flaw in Murray’s thesis is his superficial approach in contrasting the new elite’s view of “structural poverty” with what he takes to be the correct view—namely, that individuals are responsible. The new social policies failed, says Murray, because they were rooted in the assumption that the system, not the individual, is at fault.

Believing “the system” is responsible for the condition of America’s poor, the new elite thought it could change the system through federal programs. People would be lifted out of poverty and disadvantage, they thought, by receiving new opportunities in school, in job training, and through direct financial transfers. But look what happened, says Murray. It did not work. The poorest got poorer and a whole new class of disadvantaged people was created.

What does this prove? Murray thinks it proves that the “structuralists” were wrong. Therefore, we must return to the older popular wisdom: the assumption that the individual is responsible and must be held accountable by the government for his or her own behavior.

Murray’s conclusion here is wrong on two counts. First, he does not question whether the “structural reform” people took the correct approach to the structural conditions of poverty. He assumes they took the only course possible, and failed. But, if the Great Society programs did not overcome poverty, could it be because they were based on faulty assumptions about what would be required to make structural changes? Perhaps something quite different from direct income redistribution was (and will be) required; perhaps changes in tax policy and in the very identity and responsibility of industry will be necessary. In other words, perhaps there are other routes to take toward structural reform in the social, political, and economic systems that affect poverty and wealth. The failure of the welfare state to eradicate poverty (thus far) does not prove that a structuralist approach is wrong, but only that the initial war on poverty was apparently insufficient or misdirected.

Second, Murray makes too simple a distinction between the individualist approach and the structuralist approach. If it was unjust or immoral to encourage nonresponsibility via federal antipoverty programs, is it not equally immoral and unjust to presume that poverty and oppression are entirely or primarily a matter of individual initiative? Murray seems to recognize this dilemma when, after proposing to scrap “the entire federal welfare and income-support structure for working-aged persons,” he comes back quickly to say that at least one segment of the “pauperized” population will need the support of local and state services as well as the federal unemployment insurance program (pp. 227–30).

The fact is, poverty and oppression are closely connected with economic, educational, and governmental institutions as well as with the responsibility of individuals. To ignore this, as Murray seems so often to do, is to leave the wrong impression that efforts at structural reform will not work because they have already been tried and found wanting.

We must evaluate current social policy failures in the light of a public philosophy with a public policy that includes the responsibilities of both institutions and individuals. Murray’s behaviorist, individualist, utilitarian, and pragmatic criticism of failed welfare policies contrasted with “popular wisdom” is too little. At best it helps to alert us to a serious problem; but it is not adequate to lead us out of the woods.

Losing Ground: Yes

If Christian Social Activists Read only one book this year, it ought to be Charles Murray’s Losing Ground. Murray’s heavily documented study is only one of a number of recent studies that discuss how well-intended but economically unsound governmental policies have helped poverty become more entrenched in American society. His statistics show how the very War on Poverty programs that were supposed to end poverty have in fact made the plight of the poor worse. Political liberals will not like what Murray says. It not only challenges all of their cherished assumptions about how the poor need the help of a benevolent state, but serves as an indictment of liberal social policy. Murray is right! The War on Poverty programs have made things far worse for the poor in America. As Murray shows, progress in reducing poverty stopped abruptly at the very time when federal spending on social welfare programs began to climb astronomically. In the two decades since the advent of the War on Poverty programs, we have spent over a trillion dollars to relieve poverty, but all we have succeeded in doing is institutionalizing it.

There are many more people currently living below the poverty line than there were prior to the start of the War on Poverty. The poor today suffer from more crime, poorer education, higher illegitimacy rates, and more unemployment—all traceable to the very programs that were supposed to improve their lot. The quality of life among America’s poor is far worse today than before the Great Society programs; the likelihood of the poor escaping from the poverty trap is much less. While our goal was giving the poor more, what we really did was create more poor. We thought we were breaking down barriers that would help the poor escape from poverty, but we only ended up building a poverty trap from which little escape seems likely. Anyone who doubts the truth of these claims needs only to spend a short time in the abject misery of a big-city ghetto.

But what about Murray’s apparently shocking recommendation that we consider stopping all welfare programs? Well, for one thing, I suspect that even if Murray thought this was possible (which he doesn’t), his proposal is more along the lines of a heuristic device. He wants us to set aside the misconceptions that tend to cloud our judgment on such issues and think about what changes the poor themselves would begin to make—changes that could only start them in directions that would eventually improve their lives and those of their children.

Given political realities, what is needed is a total overhaul of the welfare system. Christian economist James Gwartney (Florida State University) has called for at least three reforms: (1) The system should be altered so as to reinforce and not subvert such traditional norms as work, intact families, and childbearing within marriage. (2) The reformed welfare system should give proper recognition to the importance of such voluntary organizations as churches and private charity. (3) Welfare recipients, in Gwartney’s words, “should not be allowed to use children as hostages in order to blackmail society into the acceptance of their income-transfer goals.”

In other words, we need a welfare system that will deal with the disease and not simply work to alleviate the symptoms. The welfare system must stress prevention and rehabilitation. The welfare problem in America does not need more money thrown at it; it just requires more common sense on the part of our legislators.

By Ronald Nash, head of the philosophy and religion department at Western Kentucky University.

To War on Poverty: A Christian Economist on the Bible and State Involvement

What is a scriptural view of the appropriate extent and nature of state-run antipoverty programs? How can the Bible, particularly the Old Testament, give helpful insights on this question? CHRISTIANITY TODAY has excerpted the following four principles from an address by John E. Mulford delivered to the Association of Christian Economists held in Dallas this past December.

1. The state has a legitimate role in meeting the needs of its truly poor. It may either act as an agent requiring an exchange to occur between citizens (as with gleaning, the Sabbatical, and Jubilee) or as a middleman, collecting from some people and distributing to others (as with the third-year tithe). The more complex an economy becomes, the easier it is to have the state act as a middleman dealing in dollars rather than requiring people to coordinate the exchange of goods and services.

2. The state has a responsibility to develop and apply criteria for redistributing income and wealth. In other words, recipients of transfers must have legitimate needs. Whereas in ancient Israel land ownership was the primary factor in determining an individual’s ability to provide for himself, today physical and mental health, education, and vocational skills are necessary.

3. Whenever possible, the needy person should participate in his or her own aid and sustenance. That is, self-help programs should be preferred to pure transfers. Gleaning is a good example. The recipient gathered the food rather than had it delivered.

4. In most cases, poverty should be a temporary aberration rather than a permanent affliction. State programs should help the poor escape from poverty. Interest-free loans and low-cost food were designed to help needy Israelites through tough times. In extreme cases, an Israelite would buy his countryman and treat him as a hired hand. However, the hired hand would be released and given enough supplies to start anew after six years. The implication for today is that training, education, and temporary subsidies are preferable to permanent income transfers.

Causes and cures

These principles for poverty relief require the state to assess the causes of poverty and design programs accordingly In cases where individuals are able but ill equipped or unwilling to work, the state should help educate and train them—but not support them in comfort.

Where oppression or exploitation is the primary cause of poverty, the state should actively enforce laws against exploitation and punish violators. Deceptive advertising and lending practices, contracts involving coercion or incompetence, predatory competition, and unsafe products or work environments are examples of where exploitation often occurs.

Other causes of poverty, such as the sins of previous generations or national disobedience, may fall unevenly on today’s population. As a helper of last resort, the state should be ready to provide temporary disaster relief or long-term care for the needy (orphans, handicapped, mentally ill, etc.).

Some, of course, would disagree with any active state role. A majority of people, however, would probably embrace the general propositions listed here. The differences come about in the assessment of the causes of poverty. Those who favor a very active state see oppression as a major problem. Those who want limited state involvement see unwillingness to work as most prevalent.

Both assessments warrant a caution. For the active state group: Don’t let your desire to help lead you to hinder some people. If you give to a lazy person, you generate a dependency that undermines that person’s worth. Even the New Testament church examined the needs of its members before giving to them (Acts 6; 1 Tim. 5:1–16).

And for those who think most poor people do not want to work: Consider God’s attitude of deep concern toward the poor in the Bible. Although he certainly commands man to work and condemns slothfulness, most biblical references to people who are actually in poverty involve oppression. God’s overall attitude toward the poor, as revealed in Scripture and spanning thousands of years, is one of compassion and protection.

Is our society so much different today that we can justify a much harsher, self-righteous attitude toward the poor?

By John E. Mulford, Graduate School of Business, CBN University, Virginia Beach, Virginia.

A Fallen Warrior

Fear No Evil, by David Watson (Harold Shaw, 1985, 172 pp.; $3.50 pb). Reviewed by Wayne Jacobsen, pastor, The Savior’s Community, Visalia, California.

Five days before David Watson’s departure for Fuller Seminary, a routine physical examination revealed a tumor in his colon—possibly malignant. His doctor wanted him to see a specialist the next day and be ready for surgery immediately.

“That is impossible,” Watson responded, his mind reeling with the 60 lectures he was committed to give over the next five weeks. The doctor is just being cautious, he told himself. I have to go to California. On the way home he stopped to buy a new briefcase for the trip. “A symbol of faith,” he wrote; then he added, “or was it of fear?”

Such mind-jolting honesty and vulnerability are at the heart of Fear No Evil. The trip was cancelled, and though surgery removed the tumor in his colon, it also revealed that cancer had spread to his liver. The diagnosis: inoperable. The prognosis: perhaps a year to live.

Substance Over Form

Watson was a canon in the Anglican church and perhaps the best-known clergyman in England. As a speaker and writer, his passion for church renewal was known worldwide.

Fear No Evil is this man’s story of his last 13 months; and it is a cut well above the standard fare of the ‘suffering saint’ genre. Watson’s mix of honesty and faith takes us to the depth of his pain, but also through it to the joy of triumph. He speaks of his doubts about God’s existence and the dark moments when God seemed “a million miles away and strangely silent to my frightened cries.” But these are put in context as faith prevails over doubt and as God pours out his unfailing love in moments of personal ecstasy.

Though Watson sought healing earnestly, his faith was not affirmed by changed circumstances but rather by his abiding love for the Father. No better commentary could be made of Paul’s words, “Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day.”

Watson draws us into his struggle, making it our own. When he questions himself on the boundary of actions based on faith and those on fear, we find ourselves pausing to probe our own “symbols of faith” as well.

This is a journal, not a thesis, and it does get tedious at times. Those accustomed to Watson’s tight writing style may be disappointed with form, but not content. Occasionally, thoughts are disjointed and rambling. Sentimental reflections and personal comments break the flow for those of us who don’t know the people involved. Not that any of these aren’t forgiveable under the circumstances. There are times when form must give way to substance—as here when one is never sure which words will be his last.

Willing And Wanting

Fear No Evil tells two tales. The first is a Christian’s view of suffering and impending death. While Watson’s comments on the proverbial questions of suffering bring little new to the discussion, he is at his best when walking his faith through the reality of his desperate circumstances. He rejects suffering as God-induced to purify us, though he shows us how suffering can drive people more soberly to God (and that does purify). He criticizes the notion that God brings suffering to those he trusts the most, “[If true,] I would be quite content with less trust on his part and less suffering on mine.”

His attitude toward death as a believer was aided by words from a friend whose wife had also had cancer, “We discovered the difference between being willing to go to heaven while wanting to stay on earth (for the sake of family, friends, etc.)—and wanting to go to heaven while being willing to stay on earth for others’ sake (which was Paul’s position in Philippians 1). We found great release in Paul’s …” (emphasis Watson’s). And so did Watson, though he found the change of mind a difficult one to make.

For any involved in ministry to afflicted people, Watson gives us a running commentary on which responses from people were helpful and which were not. On the helpful side were brief visits and letters when he was physically weak; times of prayer and worship that brought the presence of the Lord closer; laughter, encouragement to fight on; and even harsh realities. One doctor gently reminded Watson to prepare for his parting if his healing didn’t come: “If your disease progresses, make time for [your family], to say thank you, to ask forgiveness, and to say goodbye.”

Well-intentioned, certainly, but particularly unhelpful were too many visitors, lengthy stories of others’ tragedies, the suggestions of cancer “cures” (which only added pressure to pain), the probing for a “sin that caused the cancer,” and the explanations that he was not healed because he had not confessed it in a certain way.

Why “No”?

The second story is that of a sought healing that never came. As pastor of a congregation that regularly prays for the sick, I found this dimension particularly engrossing. At the outset of his illness, Watson admits that his observance of “faith healers” and his own experiences of praying for the sick had left him disillusioned, skeptical, cautious, and confused about God’s activity in healing. “I have not doubted that God can heal … but it has very much been the exception rather than the rule.”

During his illness, however, Watson sought the Lord for his own healing. Encouraged by the prayers and prophecies of others, Watson was convinced he would be healed. One month before his death he wrote, “I am not clinging to life, though I still believe God can heal and wants to heal.”

John Wimber was one of Watson’s closest friends. He is pastor of The Vineyard in Anaheim, California, a congregation known widely for its ministry of healing. Wimber and a team arrived in London shortly after Watson’s surgery. They prayed for healing and expressed their conviction that he would be healed. Yet, with all the prayers of their congregation and others, the disease progressed unabated.

Why wasn’t he healed? Obviously Watson did not have a chance to probe the question, so I spoke with John Wimber about his part in prayer for Watson’s healing. “If you are praying for the sick, you know you’re not healing them all,” Wimber said. “You’re watching people die in front of your eyes—lovely people, worthy people who ought to live. For some reason known only to God, he doesn’t always do what it seems apparent in Scripture he is committed to doing. And I don’t have an explanation, because God hasn’t given us one in his Word. All I can do is fight the fight, but at the end of the fight, like King David when his son died, I have to get up, take a bath, eat a sandwich, and get ready for the next one.”

Weeks before his death, Watson came to California for prayer. During that time his body swelled with the growing cancer. Wimber described it as the most “agonizing and difficult time I’ve ever been through.” In Wimber’s living room they discussed the healing they sought for and how it seemed to be eluding them. “David, as far as I know, you are a dying man. You exhibit every symptom I know about.”

“Yes, I know that’s true!” Watson responded, and they wept. “John, I want you to promise me that if I die you will not quit praying for the sick and preaching this gospel of the kingdom.”

In his book, I Believe in the Church, Watson describes the church as the army of God, battling in the greatest of all wars. Though we recognize casualties when they fall to the hand of an atheistic government, we forget the Enemy has other munitions in his arsenal. Watson was wounded, not because he was careless or sinful, but because he was in the heat of battle. All the prayers and love the church could muster could not heal the wound, and God saw fit to call him off the front lines until the final battle. We do better to honor God in that reality and Watson’s faith than to question either.

A warrior has fallen and told us his story in the going. Fear No Evil does not conclude the discussion on the place of divine healing today, but it certainly adds to it. Here is a story of hope unanswered, but not of faith destroyed.

No Simple Gift

The Simple Life: Plain Living and High Thinking in American Culture, by David Shi (Oxford Univ. Press, 1985, 332 pp.; $19.95). Reviewed by Dale Suderman, Logos Bookstore, Chicago.

The Shakers sang, “ ’Tis a gift to be simple …” But alas, that gift is both difficult to obtain and to define. It is still, however, central to American life, as David Shi demonstrates in his definitive work.

The Christian attitude toward the simple life is often contradictory. Prosperity is seen as a reward of hard work and a symbol of God’s blessing on both a personal and national scale. But somehow materialism is also seen as sin and a threat to corporate survival. Sometimes we hear both concepts in the same sermon, and wince at the seeming contradiction.

The simple life today is seen as one of three things: personal eccentricity; a carry-over from the “counterculture” of the sixties; or the mark of the true Christian. To make sense of the elusive ideal of simple living, Shi looks at its historic roots in American culture and mythology.

Simplicity Sampler

The American Puritans were determined that their “city as upon a hill,” which combined hard work, personal virtue, and a tightly regulated economy, would not fall victim to lascivious living (as in England). But their attempt to legislate simple living (wages, prices, and lifestyle were severely controlled) broke down. The wealthy chafed at their inability to display prosperity, and the poor felt oppressed under thinly veiled elitist control. Cotton Mather wrote that “religion brought forth prosperity, and the daughter destroyed the mother.”

The Great Awakening was in part an attempt to restore “felt religion and simple living” among the colonists. Revivalists such as George Whitefield not only critiqued the established clergy for formalism and cold-heartedness, but for materialism as well. At least some in the upper class saw the revivalists as breeding “anarchy, leveling and dissolution.”

Similarly, the “holy experiment” of the colonial Quakers in Pennsylvania, who “came to do good in America and ended up doing too well,” broke down. William Penn promoted simplicity while living the life of a merchant prince. The end of Quaker political control of Pennsylvania—made impossible by their inability to reconcile pacifism and the Indian wars—did free them for renewal of simple living on a personal level rather than through political structures.

Both the Quaker and Puritan ideal of a “broad and middle way” combining the simple life with material plenty failed in practice during the colonial period. The ideal was implanted in the American ethos, but never again would it be enforced by the state or a theocracy.

Revolutionary Concepts

A moral minority—ministers, political and religious idealists plus some cranks—continued to appeal to the ideal of simple living, but the wealthy would circumvent it and the poor saw it as a harsh ethic designed to keep them poor.

The Revolutionary War brought a new concept of simple living. The patriotic call to boycott British goods based on an appeal to self-sufficiency and self-sacrifice worked as long as the “sunshine patriots” were able to sell out their warehouses.

The “Republican” ideal, stated most eloquently by Samuel Adams, was a vision of a new nation freed from the “luxury and vice of Britain.” America would be a nation of farmers and small landowners with no ruling elite. The war, then, was a powerful manifestation of “simple life” as a means of social change and protest rather than social control.

But that ideal was short lived. Alexander Hamilton, among others, argued that the power of the new nation was not in “public virtue or agrarian simplicity but in public finance.” The country must have unlimited growth and with it the inevitable development of a wealth class. After all, Hamilton said, “The advantage of character belongs to the wealthy.”

In what admittedly may be an oversimplification, Shi points out that the 1980 Carter-Reagan debates had themes as old as the colonial debate about the nature of America. Carter was a Puritan preacher offering a jeremiad complete with limited economic expectations, conservation, and a corporate spiritual vision. Reagan spoke from the Hamiltonian perspective, promising economic growth and personal morality. And as in the Puritan period, large segments of the rich and the poor saw the option of expansion and growth as more attractive. Many evangelicals saw a Hollywood actor for President and “Gucci culture” as attractive, and the very phrase “Georgia peanut farmer” as a symbol of contempt.

Spiritualized Materialism

Religious idealism was a secondary consideration during the debate over economic development and the nature of the republic following the Revolution. In the end, the moral idealists were the victims of cruel irony—their hopes to “spiritualize materialism ended up materializing the spirit.”

But Christianity continued to influence the issue of simplicity. The nineteenth century saw a “cult of domesticity” in which pious women maintained spiritual values and inculcated them into their children while their husbands worked in the “real” world.

Transcendentalists such as Emerson and Thoreau developed a simple living influenced more by a romantic view of nature than by Christian faith; and the idea that God is somehow more approachable in natural settings than in cities seems almost an inherent part of simple living. (It would be fascinating to examine to what extent the God-found-in-nature idea influences church camping and retreat programs.)

But simple living has not only had a romantic rural base. In the post-Civil War period, an intellectual elite, contemptuous of both the noveau riche and worker protest movements, saw themselves as a saving remnant for the nation. They rediscovered the virtues of summer homes and camping, and supported the developing national park system. But mostly they saw themselves as gentlemen of leisure who did not pursue mammon in order that they might pursue “high thinking.” William James wrote to his brother Henry about the virtues of a summer home. “We have a first-rate hired man, a good cow, nice horse, cook, second girl, etc.” Patrician simplicity may seem odd until one compares it to intellectuals both Christian and non-Christian who may easily fall into a similar Brahmin elitism.

David Shi has written a magnificent book, weaving together disparate themes from American history into a wonderful new web of meaning without either oversimplification or shrillness. Christians, both those struggling for the simple life or contemptuous of it, cannot help but see their own beliefs in a new way if they work through this eloquent and often poetic work.

Wesley’s Many Children

The Future of the Methodist Theological Traditions, edited by M. Douglas Meeks (Abingdon Press, 1985, 224 pp.; $9.95 pb). Reviewed by Paul Bassett, professor of the history of Christianity, and director of the master of divinity program at the Nazarene Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri.

If you are one of those evangelicals who wonders what to make of Methodism (or has simply written it off as theologically whimsical), you really should read this book. It contains the “working-group” reports and major papers of the Seventh Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies, convened at Keble College, Oxford, in midsummer, 1982. These documents do not touch every issue in current Wesleyan theological discussion, but all of them are implicitly there. So in that sense, the book is comprehensive. It is also quite revealing. It can take you into the company of John Wesley’s spiritual progeny and help you hear them ponder, debate, and attempt to understand each other—if not agree.

But, of course, these are Wesley’s children, so regardless of which branch of the family they represent, they all hold it necessary and virtuous to put theology to practical use. You will hear praxis invoked at every turn. And while you may not come away convinced to see it their way (or even gratified), you will come away well informed about the current state of theological affairs among them. And you will have to take them seriously again.

M. Douglas Meeks, editor of the volume, a codirector of the institute, and a teacher at Eden Theological Seminary, St. Louis, presents the lead article under the title given to the entire collection. In a richly heuristic, nicely reasoned way, Meeks inquires about Wesleyan and Methodist theological identity and purpose. He concludes that the tradition can enjoy a healthy and useful future, especially in social reform and ecumenicity, by heeding and creatively appropriating Wesley’s elemental ideas of divine power, freedom, and justice.

Meeks believes that Wesley recast each of these traditional categories, moving them from passive “states” in God, as it were, to active expressions of his very character. At work for and in us, they make us the means of restoring to others their right to inherit true humanity. Through them, we live “in correspondence with Christ” in creative, self-giving, suffering love. Such is the doctrine and experience of “scriptural holiness” as Meeks puts it.

Wesley Repositioned And “Redefined”

Albert Outler, deeply insightful and scintillating as usual, suggests “A New Future for Wesley Studies: An Agenda for ‘Phase III’.” (Phase I—a triumphalist Wesley for triumphalist Wesleyans—and Phase II—a Wesley standing in his own right, for good or ill—remain with us, each with unique assets and liabilities.) But now we need a Wesley “repositioned,” set in his own time and studied in the light of his antecedents. Outler sets out a provisional 12-item agenda for that repositioning, and consequently he lays a foundational groundwork for most of the other papers in the book.

In presenting his agenda, however, Outler develops some interesting corollary themes. Especially significant are his comments on Wesley’s relevance. Four factors give Wesley currency, according to Outler: Wesley’s ability to see and propose alternatives to “the barren polarities generated by centuries of polemics”; Wesley’s belief that God takes the initiative in all Christian experience, social and personal; the capacity of Wesley’s theology to interact without losing its own integrity—in fact, its inherent tendency to do just that; and Wesley’s genius for wedding evangelical conversion and the ethical transformation of society.

For Outler, as for Meeks, this last factor provides the basis for understanding Wesley’s doctrine of scriptural holiness.

Taking Outler to his “outer-left” limits is Elsa Tamez, professor of biblical studies in the Seminario Biblico Latinoamericano, San José, Costa Rica, who presents a liberationist reading of Wesley in “Wesley as Read by the Poor.” Quickly noting the sociopolitical conservatism of Wesley, Tamez still wishes to keep faith with him and be Wesleyan. She appeals, therefore, to a sort of demythologized Wesley, especially when dealing with the doctrines of justification and sanctification. She believes that Wesley’s concern for the poor and for a “social creed” in preference to strict dogma are so fundamental to him that it makes room for her reading.

So, for instance, where Wesley says that sanctification is “renewal in righteousness and true holiness,” Tamez interprets, “… one loves God only if one does his will, and his will is that man should live, that he act in liberty, that he have work, food, shelter, that he celebrate, participate, that his culture be respected—in short, that he recover the image of God.”

Reading intentions is risky business. And one wonders at the process of reading Wesley as a source of eternal truths. Has Tamez reached a valid reading of Wesley by way of a questionable method? How appropriate is it to impose the reader’s context on a writer and say, “There, that’s what really was said”?

Holy Ecumenism

Picking up on Outler’s conviction that an ecumenical impulse is inherent in Wesley and in Methodism—in spite of its own divisions—is Geoffrey Wainwright, professor of systematic theology at Duke. In his “Ecclesial Location and Ecumenical Vocation,” Wainwright masterfully says that at the center of that impulse lies an insistence upon holiness, theoretical and practical. This holiness ecumenism, then, is a uniquely Wesleyan resource for the whole church. Even ecclesiastical order, that Methodist specialty, has no purpose, says Wesley, other than “bringing souls from the power of Satan to God; and to build them up in his fear and love.”

Wainwright, again following Outler, would like to see Methodism become an order within the church universal, offering to it three special “gifts” inherited from Wesley himself: its unique synthesis of “traditional Catholic, classical Protestant and Free Church Protestant concerns”; its “comprehensive drive for holiness”; and its inherently ecumenical outlook. The church itself would be of a federated sort.

There is more to this collection, of course, including pieces on evangelism and the development of faith, each somewhat distinctive in its interpretation and usage of Wesley’s theology. Yet for all its diversity, there is a coherence, and a unifying theme. That theme is not the one suggested by the title, however. Rather, it is “John Wesley, Theological Mentor: Considerations of His Doctrines of Grace and Holiness with an Eye to Application.”