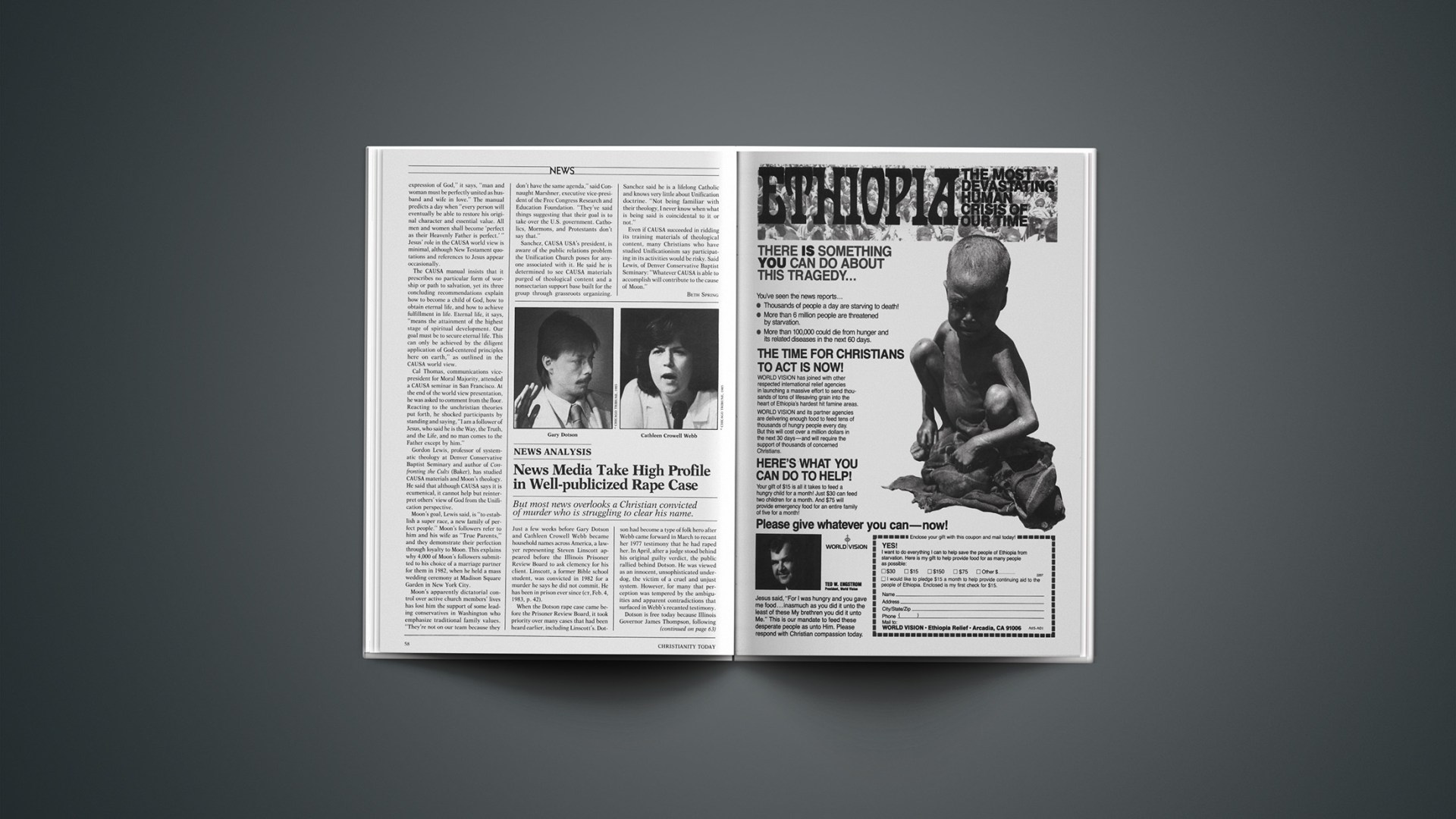

But most news overlooks a Christian convicted of murder who is struggling to clear his name.

Just a few weeks before Gary Dotson and Cathleen Crowell Webb became household names across America, a lawyer representing Steven Linscott appeared before the Illinois Prisoner Review Board to ask clemency for his client. Linscott, a former Bible school student, was convicted in 1982 for a murder he says he did not commit. He has been in prison ever since (CT, Feb. 4, 1983, p. 42).

When the Dotson rape case came before the Prisoner Review Board, it took priority over many cases that had been heard earlier, including Linscott’s. Dotson had become a type of folk hero after Webb came forward in March to recant her 1977 testimony that he had raped her. In April, after a judge stood behind his original guilty verdict, the public rallied behind Dotson. He was viewed as an innocent, unsophisticated underdog, the victim of a cruel and unjust system. However, for many that perception was tempered by the ambiguities and apparent contradictions that surfaced in Webb’s recanted testimony.

Dotson is free today because Illinois Governor James Thompson, following a special clemency hearing before the Prisoner Review Board, commuted Dotson’s 25-to 50-year prison sentence. (It is unusual for Thompson to participate in Prisoner Review Board hearings. Normally, the board hears petitions and then makes a recommendation to the governor.)

The Dotson case held a special interest for evangelicals, because Webb cited her Christian conversion in 1981 as her reason for recanting. She said she waited four years before coming forward because at first she “had only a small amount of faith, like a baby.… I had to grow until my faith could overcome my fears … that I would go to jail, that my husband would probably hate my guts.”

In a commencement address at Taylor University, Prison Fellowship chairman Charles Colson cited Webb’s recantation as an example of radical Christian living. After having talked with Webb’s pastor in New Hampshire, Colson maintains that Webb is telling the truth this time around. In his address, Colson said Webb had “demonstrated the fruits of repentance” and that she was “misunderstood probably because the world sees so little of true Christianity.”

Thompson conceded that he was troubled by the absence of a motive for Webb to lie in her recantation. Still, he said, “I don’t believe the testimony … because it was either inherently incredible or flatly contradicted by other witnesses who had no motive at all to lie.”

Although he commuted Dotson’s sentence, the Illinois governor said he was convinced Dotson is guilty. Many criticized Thompson for bowing to public pressure, pressure that was enhanced by extensive news coverage. More than 125 journalists, including national networks and the British Broadcasting Corporation, were present at the clemency hearing. Chicago’s major television stations and a few radio stations provided live coverage of all or major portions of the proceedings.

In contrast, when Linscott’s case came before the same Prisoner Review Board on April 2, it attracted only one reporter. Those on the review board were surprised, and one appeared flattered that the reporter wanted to take pictures. Thompson, of course, was not involved in Linscott’s hearing.

In 1980, Linscott, then a Bible school student in suburban Chicago, was charged with the brutal slaying of 24-year-old Karen Phillips. He was found guilty, and is serving a 40-year sentence at the Centralia (Ill.) Correctional Institute.

Unlike Dotson, Linscott had no history of trouble with the police. His conviction was based on circumstantial forensic evidence and on a dream he had of a violent murder the same night that Phillips, who lived in his neighborhood, was killed. His ordeal began when he told police about the dream. The prosecution later argued that Linscott knew details about the murder that only the real killer could have known.

After the guilty verdict, Linscott retained a new lawyer, Tom Decker, who filed for an appeal. Decker has argued that the prosecuting attorneys manufactured the forensic evidence against his client. He has said also that they mischaracterized the similarities between the dream and the real murder, and the circumstances surrounding Linscott’s disclosure of the dream. So far, there has been no decision on their request for an appeal. Decker said word from the appeals court could be imminent.

In a telephone interview, Linscott said he was amazed at how quickly the justice system moved in the Dotson case. “Most people have to wait three months for the review board to make a recommendation, who knows how long for the governor to make a decision, and then it’s usually negative.”

Linscott’s wife, Lois, said they were not bothered by the priority given to the Dotson case. “It was an unusual case that deserved special attention,” she said. “If the person who killed Karen Phillips came forward to confess, I would certainly expect immediate attention.”

Attorney Decker said that, although there are some sensational elements to the Linscott case, “it will never arouse sustained media attention because it is an extremely technical case.” Decker observed that the Dotson case contained elements that were “quite simple, quite graphic, and sexy.… [There were] some very important scientific questions in the Dotson case that were totally ignored. And had the case revolved around the scientific matters, I venture to say you wouldn’t have had any publicity.”

Decker said hundreds of cases each year call into question the propriety of a conviction or an acquittal. He lamented that the news media seem to pick up only on cases with a freakish aspect. “If we can credit the media with knowing what the public wants,” he said, “apparently the public is not interested in complex subjects.”

Linscott agrees, observing that in the Dotson case, the media “paid more attention to Cathy Webb’s semen-stained panties than to her Christian testimony.” Steven and Lois Linscott have declined to pursue opportunities to have the case aired on televison news shows like CBS’s “Sixty Minutes” and ABC’s “20/20.”

The Linscotts have been hesitant to seek media attention because they say the strength of their case lies in the facts, not in sensationalism.

Steven Linscott said he does not envy Dotson, who is free after six years in prison, but still has a felony conviction on his record. “I’m not interested in freedom without any acknowledgment of my innocence,” Linscott said. “[But] if I’m still here after six years, I might change my mind.”