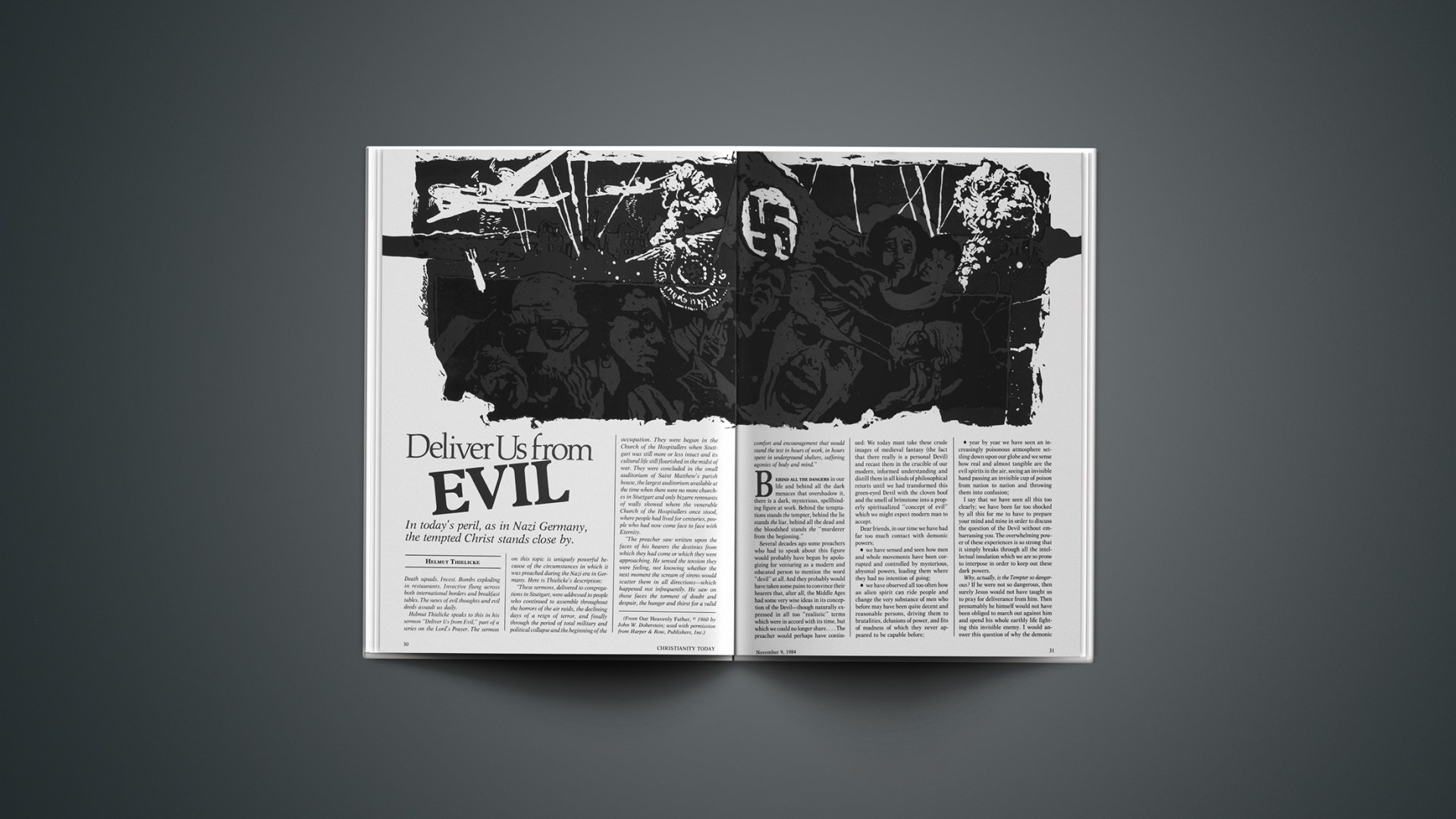

In today’s peril, as in Nazi Germany, the tempted Christ stands close by1(From Our Heavenly Father, ©1960 by John W. Doberstein; used with permission from Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.)

Death squads. Incest. Bombs exploding in restaurants. Invective flung across both international borders and breakfast tables. The news of evil thoughts and evil deeds assault us daily.

Helmut Thielicke speaks to this in his sermon “Deliver Us from Evil,” part of a series on the Lord’s Prayer. The sermon on this topic is uniquely powerful because of the circumstances in which it was preached during the Nazi era in Germany. Here is Thielicke’s description:

“These sermons, delivered to congregations in Stuttgart, were addressed to people who continued to assemble throughout the horrors of the air raids, the declining days of a reign of terror, and finally through the period of total military and political collapse and the beginning of the occupation. They were begun in the Church of the Hospitallers when Stuttgart was still more or less intact and its cultural life still flourished in the midst of war. They were concluded in the small auditorium of Saint Matthew’s parish house, the largest auditorium available at the time when there were no more churches in Stuttgart and only bizarre remnants of walls showed where the venerable Church of the Hospitallers once stood, where people had lived for centuries, people who had now come face to face with Eternity.

“The preacher saw written upon the faces of his hearers the destinies from which they had come or which they were approaching. He sensed the tension they were feeling, not knowing whether the next moment the scream of sirens would scatter them in all directions—which happened not infrequently. He saw on those faces the torment of doubt and despair, the hunger and thirst for a valid comfort and encouragement that would stand the test in hours of work, in hours spent in underground shelters, suffering agonies of body and mind.”

Behind all the dangers in our life and behind all the dark menaces that overshadow it, there is a dark, mysterious, spellbinding figure at work. Behind the temptations stands the tempter, behind the lie stands the liar, behind all the dead and the bloodshed stands the “murderer from the beginning.”

Several decades ago some preachers who had to speak about this figure would probably have begun by apologizing for venturing as a modern and educated person to mention the word “devil” at all. And they probably would have taken some pains to convince their hearers that, after all, the Middle Ages had some very wise ideas in its conception of the Devil—though naturally expressed in all too “realistic” terms which were in accord with its time, but which we could no longer share.… The preacher would perhaps have continued: We today must take these crude images of medieval fantasy (the fact that there really is a personal Devil) and recast them in the crucible of our modern, informed understanding and distill them in all kinds of philosophical retorts until we had transformed this green-eyed Devil with the cloven hoof and the smell of brimstone into a properly spiritualized “concept of evil” which we might expect modern man to accept.

Dear friends, in our time we have had far too much contact with demonic powers;

• we have sensed and seen how men and whole movements have been corrupted and controlled by mysterious, abysmal powers, leading them where they had no intention of going;

• we have observed all too often how an alien spirit can ride people and change the very substance of men who before may have been quite decent and reasonable persons, driving them to brutalities, delusions of power, and fits of madness of which they never appeared to be capable before;

• year by year we have seen an increasingly poisonous atmosphere settling down upon our globe and we sense how real and almost tangible are the evil spirits in the air, seeing an invisible hand passing an invisible cup of poison from nation to nation and throwing them into confusion;

I say that we have seen all this too clearly; we have been far too shocked by all this for me to have to prepare your mind and mine in order to discuss the question of the Devil without embarrassing you. The overwhelming power of these experiences is so strong that it simply breaks through all the intellectual insulation which we are so prone to interpose in order to keep out these dark powers.

Why, actually, is the Tempter so dangerous? If he were not so dangerous, then surely Jesus would not have taught us to pray for deliverance from him. Then presumably he himself would not have been obliged to march out against him and spend his whole earthly life fighting this invisible enemy. I would answer this question of why the demonic power is so dangerous simply by saying that it is because he cannot be recognized, simply because he does not have the characteristic hoofs by which one could recognize him. If he had a passport, under the heading “Special Characteristics” there would be written “None.” The Devil is a master of disguise, and one important specialty of his tactics consists in his hiding behind positive values and ideals.

This can be illustrated by means of a simple, everyday example. When a seducer tries to bring another person into his power, he certainly does not begin by saying, “Come, I’ll teach you something evil; I’ll show you a sin.” If he were to begin his seduction in such a foolish way, our conscience would doubtless be shocked and we would seek to escape the temptation.

But the Tempter would never begin in such a stupid way. He always tries to represent his offer as something that will lead to positive and significant goals. So he says, “Come, I will teach you something interesting, something pleasurable, something that will give you a glorious thrill and give you the chance to live to the full.” The classical example of this technique of temptation was demonstrated in the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness.

As we discuss this a bit, and since this will require us to look into some deep abysses, we must from the beginning hold fast to this tremendously comforting thought: At the most perilous point in our life, namely, the place where we must do battle with the Tempter for life or death, there Jesus stood too, there he stands beside us. His heart too was shaken by the grandiose jugglery with which the Tempter tried to bemuse him. For, as we have said, what the Tempter does always has stature. It never lacks grand perspectives and the touch of idealism. But he who has the Lord beside him, that Lord who was “tempted as we are” and stands in the same rank with us, he who has beside him this Lord against whom the Tempter’s charm could not prevail—the person’s faith then begins to operate like a kind of divining rod by which he is able to “distinguish between spirits” and which reacts immediately whenever the Devil appears, no matter how deceiving his mask may be, whether he disguises himself as national idealism, or a democratic order that is going to make the whole world happy, whether he comes with a Bible in his hand or dripping with the oil of pious phrases, or whether he operates with the doctrines of some plausible-sounding and seemingly sound philosophy. The Lord who stood in the wilderness never departs from his own when the hour of temptation breaks in upon them.

Jesus is the Victor! He has already won, and all our struggles are only rearguard battles and mop-up actions, all of which are under the sign of that victory which the Lord achieved for us all in the wilderness.

And yet how positive and appealing are the means with which the Tempter operates! To understand this we need only to think of the third temptation, in which the Devil took Jesus to a very high mountain where all the kingdoms of the world and their glory lay spread out before him: “All these will I give you …!”

What a heady, intoxicating prospect that was! When the Devil offered him the kingdoms of the world he was by no means appealing only to the baser instincts, the vile thirst to satisfy the ambition to secure one zone of influence after another, or the brutal urge to power that hankers for dominion. No, he was appealing, as it were, to Jesus’ “idealism” and the highest aspirations of his soul; for if Jesus were elevated to the sovereignty of the world this would seem to give him the opportunity to use his power to the glory of God and carry on the mighty work of “Christianizing the world.” Would not any human heart, even the heart of the Son of God, tremble at the magnitude of this idea? If this were so, if the whole earth were led to Christianity “with power,” then the disciples would no longer need to have the oppressive feeling that they were so defenseless and exposed and that the history of the world was passing them by and paying no heed to them. Then they would cease to be “only” the quiet in the land, ignored by the loud, rushing stream of world events. Then they would no longer face the depressing embarrassment of not being able to prove the existence and power of their Lord when they were asked. Then, when the terrible catastrophes struck and the specter of doubt and despair of God lifted its head, they would no longer need to blush in silence when the godless raised their malicious question: “Where is your God?”

All this would suddenly be changed—if Jesus were the sovereign of the world, if he had the armies and their flags and standards at his disposal.

No missionary would ever again be left defenseless on alien coasts to face the butchers of men, if—yes, if Jesus were the sovereign of the world.

Is not this in fact a great idea, a positively dizzying prospect?

Or we think of the first temptation, in which the Devil tries to induce the Lord to turn stones into bread. Here Jesus suddenly sees himself confronted with this tremendous possibility: I could provide men with bread! I could perform this undreamed of act of brotherly love by feeding the hungry. This in itself must have been an extraordinarily powerful and appealing motive. But when we examine it closer, the charm of this devilish overture becomes still greater. The implications of providing bread are by no means confined to the body. They involve infinitely more than that. The satisfaction of hunger would immediately entail tremendous intellectual consequences, for do we not control the minds of men when we control their bread? When people have food and clothing and shelter, they usually “join the parade.” Then they get over their conscientious scruples and renounce their old faith with relatively light hearts and find the new gods quite unobjectionable. There have been many hunger revolts in history, but not many based on conviction. The food question is really one of the keys to world history. All this the Tempter intimated to the Lord. And again, isn’t this a great idea: If I can bind people to myself and get them to sing my tune by feeding them, why shouldn’t I try to bind them to God in this way?

So it is possible that the right solution of the food problem may have enormous significance for the kingdom of God and its extension.

But the bemusing questions which the Tempter keeps trying to drop like sweet poison into the mind of Jesus go even further. Feeling the impact of this Satanic insinuation, Jesus must now ask himself: Will not many become unfaithful to me (this is surely what the Devil was suggesting) simply because they will be afraid—and quite rightly—that they will lose their jobs and their bread, if they follow me? It may be costly for them to confess me. Many will therefore shun this confession or throw it overboard when the pinch comes. But the moment I give them bread the dilemma will be solved, and suddenly the conflict between God and “goods, fame, child, and wife” will vanish. Then the Christian faith will be popular for there will be no risks involved. I could turn millions of adherents, who simply flinch from me as long as I remain only an invisible and seemingly helpless Lord, into my most faithful followers. Ought I not therefore to give bread for God’s sake and the sake of these millions? Ought I not to restrict the risk and the venture that faith demands? Ought I not to make discipleship a rewarding and paying proposition? Otherwise, what will happen to the great masses who are out after bread and circuses? Does not love and compassion demand that I couple the kingdom of God and the breadbasket, and reward my adherents with food?

And again the question arises: Is not this a great idea of the Devil, which might be a solution to the deepest conflicts of human life?

And the second temptation, that Jesus throw himself down from the pinnacle of the temple—naturally, on the Sabbath when a great crowd would be present to be astonished by the feat—this second temptation too has a seductive grandeur about it. What it means is that the Tempter is challenging the Son of God to indulge in publicity and propaganda. He is suggesting to him something like this:

“Now, Jesus of Nazareth, you are starting out all wrong, if you think you can win people and call them to decision by preaching and ministering and personal encounter. Most people do not have the maturity to deal with such personal questions anyhow.

“Do you have such poor knowledge of people, Jesus of Nazareth, that you insist on riding their consciences? Just look at them: most of them have no wills at all; they are conscienceless copies of the great mass who swim along with the crowd and are pushed around by every wind that blows. They are purely sensual beings, moved not by ideas but by sensations and impressions. Look at any show or night club, Jesus of Nazareth! There they are—all spectators: the fools and the intelligent, the upright and the scoundrels. And all of them gaze entranced at the stage where the artists perform their tricks. Their hearts stop beating when the acrobat makes his mortal leap, and they all break out in one single burst of applause when the trick succeeds and the nervous tension is released. Look at them, Jesus of Nazareth; it’s their nerves you have to appeal to, for they all have nerves and they react immediately with their nerves. You should get this straight, Jesus of Nazareth: As far as the great masses are concerned, the conscience is a completely secondary organ. Most people do not live by their conscience at all. They do not live on the basis of responsibility and personal decision. They live by their nerves, their sensations, the herd instinct. If you want to win the world (even if you want to win it for God), you will have to satisfy their primitive sensuality, their need to have their nerves titillated. If you can impress them there, they will flock after you, and they will also believe what you tell them about the higher things of life. After all, Jesus of Nazareth, what you are telling them is something good (says the Devil!). After all, you want to lead them to your Father. Why shouldn’t you condition their hearts with the propaganda appeal to their senses? Then they will also be able to take in the higher message you proclaim as a ‘redeemer.’ ”

This idea, too, is not without greatness. It could put Jesus’ mission on a totally new and tremendously promising basis.

In short, everything the Devil says is enormously positive. These are stupendous goals, staggering in their persuasiveness.

And yet these ideals and grand prospects are nothing but a delusive cloak to cover up—now let us say it—a cloven hoof, to cover up the fact that all this would only serve the Devil: “If you will fall down and worship me!”

In order to understand why this is so, let us think back to the third temptation, to the moment when the Devil offered Christ all the kingdoms of the world.

In the thousand years of Christian history that lie behind us we have actually learned something about the chances and temptations inherent in this moment. For this millennium, which is now coming to an end, was the Constantinian age of the church. It offered the intoxicating opportunity for Christianity to enter into a secure alliance with the public, above all with the state. One need only think of the motto, “Throne and Altar,” to understand this. The schools were almost automatically Christian schools; the press was for the most part at the disposal of the church; the guilds had their reserved places in the sanctuaries. Did not this firm alliance of church and state, of parish and public, present a tremendous chance for Christianity to permeate all the areas of life? Was this not an impressive expression of Christ’s claim upon the whole of human life?

But now, since 1933, we have seen this “wholesale” Christianity of the great masses and mere “holders of baptismal certificates” simply collapse because it led only to a Christian façade for public life, behind which lingered the gods and myths of a pagan and atheistic age, gods and myths that were only waiting for the moment when they could tear down the facade and proclaim their dominion openly.

And surely they have done this impressively and consistently enough. Can any of us be anything but utterly astonished at the manifestations of paganism and neopaganism that suddenly appeared among our nominally Christian people? Would we ever have thought it possible that, in a country in which almost everybody was baptized and confirmed or at least brought up under Christian influence, hundreds of thousands would gather together in the Berlin Sports Palace and the largest auditoriums in every city and cheer themselves hoarse over the German faith-movement and other pagan ideologies?

Suddenly God led his church out of its accustomed public place in the Constantinian age. He allowed it to be driven into the ghetto of its own church walls and in some instance into the catacombs. And in these narrow places there occurred with God’s help a process of maturation that caused the church to find its way back to the substance of its message and its biblical foundations. The very fact that God took from the church its public position was a demonstration of his gracious providence, whereby he separated the wheat from the confusing chaff, cleared the jungle of so-called Christianity of everything except the two towering trees of “Scripture and confession,” brought forth the “holy remnant,” and sustained his church through it all.

Not that this ghetto is the ideal, not that the church should remain within its walls and renounce the world! I should hope never to be so misunderstood. But it does make a difference whether the world is simply labeled as Christian by higher authorities and surrounded with a Christian façade, thus creating a mere Potemkin village of sham Christianity, or whether a church which has been matured in the ghetto and catacombs, a “holy remnant,” tempted and tested in the fires of suffering, emerges from these walls and with authority proclaims Christ’s dominion over the world. This was the only interpretation that Jesus put upon the Great Commission when he commanded the disciples to go out into the world in the name of their Lord to whom all power was given.

The other temptation—to exercise power by means of bread and control of the sources of food—is perhaps the peril of the church of Jesus today. For, after all, we face the fact that the church is one of the very few trusted factors from the past that survived the great deluge. This act has its greatness but also its dangers. The church of Jesus and its bishops are now solicited for aid and counsel in many public affairs, even in political matters. The church of Jesus has the opportunity—at least for a brief period—to exercise power, to make use of the long lever, and by possible joint control of the food supply to bring people into the sphere of its influence.

Woe to it, if it does so! Woe to it, if it seeks to achieve its destiny of leading men to the Cross and bringing them into a living personal relationship with Jesus Christ by employing the instruments of power and the breadbasket! Woe to it, if even in a single case it allows the fact that a person is a member of the church or has left the church to work to his advantage or detriment! Then we would soon have exchanged the red and the brown terror for the black terror. And the black terror would be the worst, for in the other forms of terror only men are dishonored, whereas this most dreadful species of tyranny would desecrate the very Cross on which the Lord Christ died in helplessness in order to bring the world back home.

Woe to it, if the church of Jesus does not remain beneath this powerless Cross, if it does not speak out openly—no matter what the powers and pressures are that make it necessary—and say what is right and what is wrong, at least as clearly as it has sometimes done under past dictators!

Woe to it, if it does not prefer to give up all its influence rather than deny the truth, if it is not prepared to be like a sheep among wolves, no matter what the nationality of these wolves may be! The church has no other mission except to proclaim the commandments of God and to tell the imprisoned that they are free, the blind that they shall see, and the guilty and heavy laden that the Cross of Calvary is there for them. It was not for nothing that God allowed the church of Jesus to suffer for twelve years, and thus brought it to a place of blessing which we dare not now deny.

It is only human, “all too human,” that someone who has been in a concentration camp for Jesus’ sake or—as in my own case—dismissed, forbidden to travel or to speak, and hampered in every way, should now desire to get back into the stream of things and go ahead at full speed, to have the feeling of “power” he has been deprived of for so long, in order to make up for the time lost.

I say this is “human, all too human,” and we are actually seeing some evidences of this human delight in power within the church. But we must have nothing to do with it. This is not what Jesus Christ died for! The church of Jesus has no business to take revenge or to sit in judgment. The church must be a mother to all who are weary and heavy laden, to all who have strayed and gone wrong—even to those who have forsaken their mother in the last decade and fallen victim to strange ideas. And therefore its task is not to look to the great and powerful, to the “Americans” and the “English,” but rather to visit the prisoners and preach the gospel to those who cannot help the church because they have no privileges to bestow.

Jesus himself quite consciously passed up the great chances and the great moments for making propaganda in his life. When he had the chance to speak to great crowds, when he might have taken advantage of the wildest ovations of enthusiastic hearers, he made his way through the midst of them and went away to be alone with God or to help a sick person or a burdened conscience. This was precisely the time when he turned to the individual, who was completely lacking in influence and could not make him king. So the church too must bear witness to the truth and the love of God in this unpopular way and turn to those who need its help and comfort. Who was ever more unpopular than its Master? But the servant dare not be above his master.

So Jesus saw through the intoxicating visions and glittering prospects which the Devil conjured up before him. He renounced power—even the power that he might have used for his purpose, the Christianization of the world. He knew that the very substance of his message would be altered and falsified if the child were put under the slightest compulsion to go back home to the Father, for then the child would become a slave and the Father a tyrant.

So he rose up from the place where the kingdoms of the world shimmered before him, where crowns flashed and banners rustled, and hosts of enthusiastic people were ready to acclaim him, and he quietly walked the way of poverty and suffering to the Cross.

He walked the road where the great and the rich of this world will despise him, but where he is the brother of sinners, the companion of the forsaken and lonely, the sharer of the lot of all who are shelterless and know not where to lay their head, the comrade of the insulted and injured, to whom he reaches down from his shameful Cross.

With all these he associates himself, he who could have possessed the whole world.

And that is why the story closes with the angels ministering to him, which means that the presence of the Father was with him. The angels will always be where he is, even, and most particularly, in the darkest places of his journey through the deep. And in Gethsemane, too, one of them will come to him and strengthen him.

Did he stake his life on the wrong card, this Jesus of Nazareth? Did he make a bad exchange when in the hour of temptation he preferred the presence of the angels and the presence of the Father to the riches of this world? If he had accepted the riches of this world and their “glory” he would be forgotten today. He would have become a great king in history, recorded in the history books of our schools. He would have become a venerated museum piece—if he had signed the pact with the Devil. But because he suffered and in suffering learned obedience, he has become our brother and our king, and therefore we too know that this is our destiny:

And he who fain would kiss, embrace

This little Child with gladness

Must first endure with him in grace

The rack of pain and sadness.

We must not only die to the baser powers of temptations, the enchantment and allure of the senses and the wild fever of revenge and ambition—for when we are bewitched by these we cannot hear the “voice”—but we must also be willing to die to the “ideal” motives, to “goods, honor, child, and wife.” We must even maintain a certain distance from the great and gladsome, dear and familiar things of this world, as we saw in the picture of the “Knight, Death, and the Devil.” And the truth is that this is no small thing. All of it is painful, it is all a “rack of pain and sadness,” or at least can become so. But because of it we can embrace him and know the presence of the angels. God is blessed and because of this blessedness all this is worthwhile. Never will we regret it if we choose the way of the Cross in the hour of temptation, for it is the way of the Master. In every case God is richer than the Devil is evil; and none who has ever followed him has ever regretted the “rack of pain and sadness.”

May the church of Jesus not dream away the hour to which it has now been called. It faces great promises and terrible temptations. May the church be a mother who bends low to help the lost and defend their cause; and may it not become a courtesan who looks with longing glances at the glory of the mighty.

May it be a comforting beacon, proclaiming to all men that at least in one place in this world of hate and revenge there is love, because, beyond all comprehension, the Son of God died for this world. And if it must preach judgment, if it must call down woe upon the people and interpret the fearful signs of the times, then may it never do so pharisaically, as one who had no share in the great guilt. But rather may it do so as a mother, whose own soul is pierced through by a sword; may it do so as did Jesus Christ himself, who uttered the cry of judgment over Jerusalem in a voice that was choked with tears.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).