How do we mix the oil and water of evangelism and social responsibility? Delegates in Grand Rapids wrestle with an important issue discussed in “The Other Side of Thanksgiving.”

What is the relationship between the Great Commission (to go into all the world and preach the gospel) and the Great Commandment (to love God and to love one’s neighbor as oneself)? How do evangelism and social responsibility relate?

Are they different sides of the same coin—or competitors? Mission executives increasingly complain that relief and development agencies get a growing share of a finite evangelical dollar. Other opinion leaders insist it is high time evangelicals paid more attention to the needs of 800 million fellow humans who live near the margins of survival. They assert that the traditional emphasis on preaching the gospel and on church growth is a distortion of the real mandate of God’s people in the world.

The Consultation on the Relationship between Evangelism and Social Responsibility held at Grand Rapids, Michigan, last June grasped a nettle that has been a major irritant at international evangelical gatherings for more than a decade. By facing these issues squarely its sponsors hoped to produce a document that would defuse tensions and help unite Christians whose perceptions of Christian responsibility were leading them to stress different priorities, threatening to produce overt disunity within the worldwide evangelical movement.

The structure of the consultation was designed with great care by a joint committee established by the World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF) and the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization (LCWE) to coordinate their most important joint exercise to date. Forty-two participants and ten consultants from 27 countries were hosted for six days by president Dick Van Halsema at his beautiful Reformed Bible College campus.

Senior evangelical leaders participating included Leighton Ford of LCWE and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association; Wade Coggins and Bruce Nicholls of WEF; John R. W. Stott, rector emeritus of All Souls Church, London; Ed Dayton of World Vision; Harold Lindsell, editor emeritus of CHRISTIANITY TODAY; and John Perkins of Voice of Calvary, Mississippi. But chairmanship of the consultation was in the hands of such younger men as Gottfried Osei-Mensah of Ghana (LCWE director) and Bong Rin Ro of Taiwan (WEF). Other non-Western leaders included David Gitari, Anglican bishop of East Kenya, Tokunboh Adeyemo of the Association of Evangelicals of Africa and Madagascar, and John Richard of the Evangelical Fellowship of India.

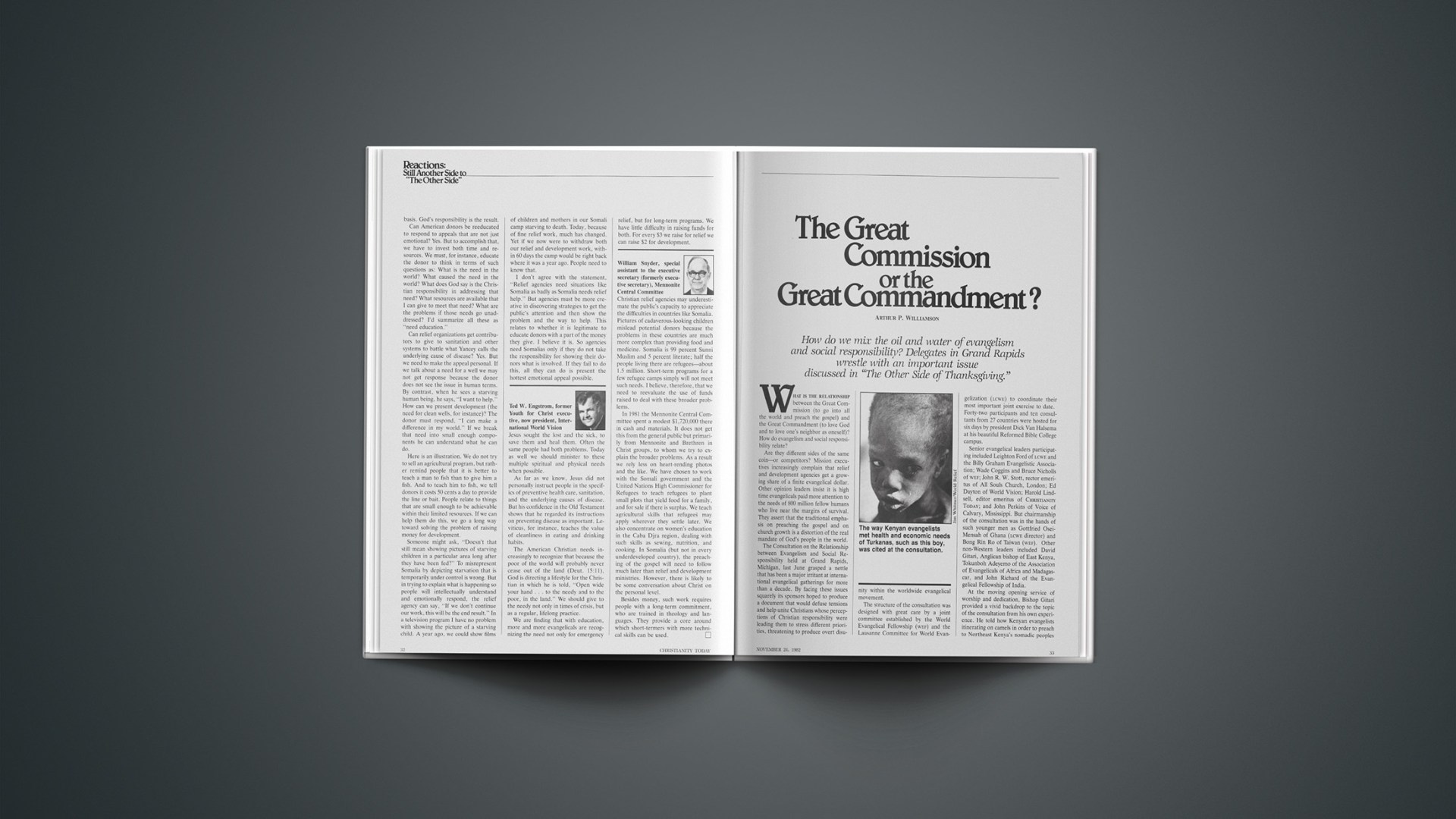

At the moving opening service of worship and dedication, Bishop Gitari provided a vivid backdrop to the topic of the consultation from his own experience. He told how Kenyan evangelists itinerating on camels in order to preach to Northeast Kenya’s nomadic peoples had won numerous converts. Their grave health and economic needs quickly caused evangelistic concern to merge with social action. The church developed a holistic program of pastoral care and social transformation that deeply marked that part of Kenya.

Leighton Ford set out the ground rules. Many, he said, had expressed apprehension about the Grand Rapids event, fearing that the gathering could widen and solidify divisions in the worldwide evangelical movement. He reminded members that the consultation had been called to “clarify but not to change” the Lausanne Covenant identification of Christian duty as involving “both evangelism and sociopolitical responsibility.”

At the 1974 Lausanne Congress there was sharp disagreement over this issue. John Stott called social action a partner of evangelism, but was accused by Trinity Evangelical Divinity School professor Arthur Johnston of having “dethroned evangelism as the only historical aim of mission.” An unofficial Radical Discipleship Group produced a paper rejecting as “demonic” any effort to “drive a wedge between evangelism and social justice.” The Lausanne Covenant defined evangelism as the primary mission of the church, but Ron Sider wrote that to define any task of the church as primary was “unbiblical and misleading.” René Padilla from Buenos Aires, writing in 1976 in The New Face of Evangelicalism, which he edited, said that “the Covenant is a death blow to the superficial equation of the Christian mission with the multiplication of Christians and churches.”

Four years later, at Pattaya, Thailand, the same issue was again prominent. One third of the members called on the Lausanne committee to convene a world conference on evangelism and social responsibility. The Grand Rapids consultation was the result.

The consultation was structured around plenary sessions to introduce and discuss major papers, small groups to explore major issues in depth, and case studies to present examples of Christian social responsibility in situations as diverse as India, Mississippi, Burma, and the Philippines. Group reports were submitted each day to a drafting committee chaired by John Stott, who was assisted by David Wells of Gordon-Conwell Seminary. The final day and a half of the consultation was devoted to a line-by-line consideration of the report, a 40-page document that went through a number of drafts and was not yet in final form by publication date.

By the second day issues began to surface, sometimes gently, sometimes contentiously. Most of the questions clustered around four themes: What is mission? How broad is salvation in Scripture? How does the Lord’s teaching on the kingdom relate to the mission of the church and to Paul’s model of evangelism? and, What is the mandate of Christians concerning social justice (as distinct from social service)? On each of these questions most members brought with them views reflecting presuppositions that were usually theological but just as often also political.

From these key issues other topics teemed: Does the church-growth emphasis on numbers necessarily deemphasize discipleship? Is some contemporary thinking about mission based on ideas that originate in the World Council of Churches, which contributed to the demise of the International Missionary Council and which has decimated ecumenical missions since World War II? Are evangelicals who accept some of liberation theology’s propositions on their way to articulating a gospel that will rationalize and encourage violence and even killing in the name of Christ?

With such volatile issues on the agenda for up to 14 hours each day, debate was sometimes tough. Statesmanlike leadership, by Osei-Mensah and Adeyemo in particular, defused difficult moments in the plenary sessions. Small group leaders needed all their skills to balance the vigorous opinions expressed by participants.

A recurring pronouncement at the consultation was that the church should be affirming the lordship of Christ over all demonic powers of evil that “possess persons, pervade structures, societies, and the created order.” In the radical discipleship stream, Anglican pastor Vinay Samuel of Bangalore, India, and his English colleague Chris Sugden crusaded with vigor and enthusiasm for this definition and understanding of the mission of the church. Their stand was seconded by Padilla and a minority of consultation members. Some participants challenged their views, asserting that their writings strongly reflect nonevangelical theological positions about the nature of salvation. Socioeconomic improvements are described as an aspect of salvation by those who broadly interpret the Bible’s salvation language, building on the fact that salvation has not only personal but also social and cosmic dimensions.

Ron Sider (Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger) and James I. Packer explored this subject in a carefully argued paper. To the surprise of some participants (and to his own, Sider admitted), the paper came down on the side of a narrow use of salvation language: “We find it less confusing and more faithful to biblical usage to restrict salvation language to the sphere of conscious confession of faith in Christ.” Sider’s conclusion removed one of the main props of evangelicals who accept the conceptual categories adopted by the World Council of Churches at its Bangkok assembly in 1973, where it was stated that “salvation is the peace of the people of Vietnam, independence in Angola … justice and reconciliation in Northern Ireland.”

In the Samuel-Sugden firing line for hewing to the primacy of evangelism in the mission of the church was Arthur Johnston (Battle for World Evangelism, 1978), together with Donald McGavran, founder and mentor of the church growth movement and, by implication, Peter Wagner of the School of Church Growth at Fuller Theological Seminary. Johnston was joined in his defense by Peter Beyerhaus of Tübingen, Germany, Klaus Bockmühl (Regent College, Vancouver), Harold Lindsell, and Wagner.

Many consultation participants construed Luke 4:16–21 and its parallel passage in Isaiah 61:1–2 in a quasi-political sense, suggesting that today’s church should be involved in “proclaiming release to captives and setting at liberty the oppressed.” Johnston insisted that Christians must distinguish between the theocratic institution and mission of Israel and that of Jesus and the church inaugurated at Pentecost.

Both Beyerhaus and Johnston referred to the influence of Jürgen Moltman, author of A Theology of Hope (1967) and a colleague of Beyerhaus at Tübingen, who has laid much of the intellectual foundation of liberation theology. Moltman does not distinguish between the kingdom and the church. His vision of the future appears to involve the reign of God apart from judgment. That reign is foreshadowed by present sociopolitical accomplishments. Beyerhaus suggested that the writings of Moltman (and his teacher Ernst Bloch) have contributed significantly to the development of ecumenical missiology, especially the emerging utopic vision in the World Council of Churches.

Focusing on the doctrine of the kingdom as the source of a theology of social responsibility is a departure for evangelicals. Until recently, the source for most of them working in this field was the doctrine of creation. By contrast, Walter Rauschenbusch, the most famous theologian of the social gospel movement, developed a theology of social reform and political action deriving from a theology of the kingdom in his major work, A Theology for the Social Gospel (1919). What direction this new—for evangelicals—approach will develop, and whether it will lead to new unraveling among different strands of theological emphasis, remains to be seen.

Post- and amillenialists asserted that evangelism is the proclamation of Jesus’ kingly reign and authority in this age. Therefore, they said, Christians, as “representatives of the kingdom,” should be deeply involved in issues of social justice and in consequent political action. The Anabaptist view at the consultation tended broadly to endorse these strong social justice concerns but with a less-clearly worked out eschatology and the insistence that only nonviolent methods are options for Christians.

Premillenialists tended to pessimism about the possibility of significant moral transformation before the return of Christ. They stressed the primacy of evangelism and insisted that evangelism is itself a fundamental form of social action. They did not claim, though, that it should have a priority of ministry, and accepted that social assistance might be the most appropriate first response to a situation of grave human need.

Several recent writers on the history of evangelicalism have claimed a causal relationship between the rise of premillenialism and the decline of social concern among evangelicals. The consultation explored this alleged link and disallowed it. Instead it declared that premillenial evangelicals in the early twentieth century reacted against the optimistic thrust of the social gospel movement and stressed the lostness of man without Christ and hence the urgency of the evangelistic task. This emphasis may have lessened social involvement by some evangelicals in the North American setting, but it led to a massive increase in Christian caring in the Third World. Hundreds of hospitals and leprosariums were established, and literacy and primary education became major emphases of evangelical, often premillenial, missions.

Eschatology also impinges on a weighty question for Christian relief and development agencies as they frame policy and spending priorities. Where does social justice diverge from social assistance? People of different millenial persuasions join in supporting involvement in relief and social assistance. But questions of justice and development lead to divergence, raising as they do highly political economic and class issues.

It was stated that not to express a judgment concerning injustice and exploitation is to support tacitly an unjust status quo. Some argued that the church, as church, should be involved in the fight for justice; others said believers should work as individuals for justice and equity, demonstrating Christ’s reign in their own lives. Padilla lamented that Latin American evangelicals often align themselves self-interestedly with political forces of reaction. Emilio Nunez of Guatemala acknowledged that the church in Latin America has “played the game for the political Right” but warned that it must not now repeat its naïveté and serve the purposes of the Left.

Participants were not asked to endorse or sign the report of the consultation. But they did consider the first draft, and received a third draft following the consultation. Running to more than 23,000 words, it may prove the most influential evangelical document of the 1980s. John Stott’s experience and industry served the consultation well. He skillfully summarized areas of consensus without concealing divergent principles of biblical interpretation or understandings of Christian social responsibility, stemming from differing theological traditions and cultural or ideological contexts.

In the report, three kinds of evangelism-social responsibility relationship are identified: social responsibility as a consequence of evangelism, social action as a bridge to evangelism, and social concern as a partner of evangelism. In a memorable section on the question of primacy, the report says: “Seldom if ever should we have to choose between satisfying physical hunger and spiritual hunger, or between healing bodies or saving souls, since an authentic love for our neighbor will lead us to serve him or her as a whole person. Nevertheless, if we must choose, then we have to say that the supreme and ultimate need of all mankind is the saving grace of Jesus Christ and therefore a person’s eternal spiritual salvation is of greater importance than his or her temporal and material well-being.”

The report distinguishes carefully between social responsibility, to which Christians are called, and what it identifies as “false dreams” for the future of human society that are generated by both Marxist and Western materialistic ideologies.

The final report section, entitled “Guidelines for Action.” will probably be the most quoted. Distinguishing functionally between what it calls social service and social action, a short crucial passage delineates the meaning of “socio-political involvement,” the Lausanne Covenant phrase that the consultation had set out to clarify. The report rejects political action entailing civil strife or revolution; it endorses political action consistent with biblical principles where such action is possible.

A major subsection urges that local churches should teach Christians to think in a Christian manner about social issues and questions. But it cautions that where Scripture is unclear churches should beware making pronouncements that would create controversy. The local church should normally avoid partisan politics but should not shirk a prophetic ministry, proclaiming the law of God. It should also seek to meet social, emotional, and physical need, and work for the well-being of society.

The guidelines call Christians in affluent areas of the world to adopt a lifestyle of simplicity and contentment, releasing funds for evangelistic and social enterprises around the world.

Did the grand rapids consultation achieve its stated aim of clarifying the relationship of evangelism and social responsibility? It would be futile to attempt a definitive assessment so soon. But certain features are already clear.

The report is a major evangelical document. Its solid strength lies principally in its practical sections, though its theological chapters are also of great value as a discussion of the issues. The guidelines will undoubtedly help Christians in all kinds of situations and will serve churches and individuals around the world as a foundational reference source.

But the consultation by its very nature did not—and probably could not resolve the underlying theological questions. The meagerness of primary biblical investigation of the issues was disappointing. The focus was theological. Apart from introductory morning Bible studies, there was little explicit consideration of the plenteous biblical material concerning the results of evangelism in the early church, and the relationship between the Christian faith as believed and as lived by the early church. Many of the tensions among evangelicals exposed at the consultation are deeply rooted in divergent approaches to biblical revelation and are based on conflicting views of the nature of the church. Greater evangelical oneness awaits a Holy Spirit-guided deeper understanding of the wisdom and will of God.

Grand Rapids took a major step in clarifying issues related to evangelism and social responsibility and in developing guidelines for action. But many important questions about the content of biblical revelation remain to be tackled if greater evangelical unanimity is to be achieved.

Arthur P. Williamson teaches at the New University of Ulster in Northern Ireland. His field is social policy. He is coeditor of Violence and Social Services in Northern Ireland (Heineman Educational Books, London, 1978).