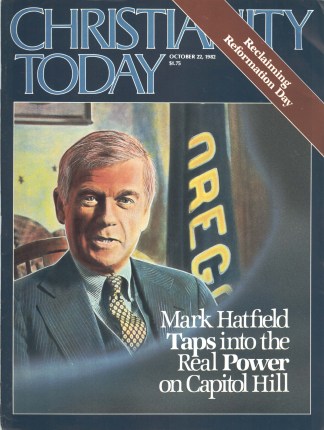

The senior senator from Oregon shows keen discernment between the power of politics and the power wielded by the Holy Spirit.

What makes Sen. Mark Hatfield so different? Newsmen and radio commentators find it difficult to place him in a neat pigeonhole. As the New York Times puts it: “Mr. Hatfield does not fit the mold.” He is a Republican, but is known as a liberal in politics. He is against nuclear war, but he is not a pacifist. He supports all sorts of programs to aid the poor, but he is a diehard fiscal conservative. He is a friend of Billy Graham, and he cosponsors a resolution with Sen. Edward Kennedy. He has never been a “wheel” of the Senate’s power structure, but he has become chairman of the powerful Appropriations Committee. He antagonizes his Oregon constituency by voting flatly against a measure 90 percent of them badly want, and they turn right around and reelect him to office. He is a devout evangelical and an active member of Georgetown Baptist Church, but no fundamentalist or evangelical organization has him in its pocket.

What makes that kind of man? We believe this interview will reveal his secret: it is his deep commitment to Jesus Christ and a conscience structured and refined by Holy Scripture as his own final rule of faith and practice.

Senator, would you describe your spiritual and religious roots?

I am convinced that a person carries the imprint of his environment. I had the advantage of being raised in a small community. From that experience of knowing neighborhood and neighbors came a real sense of community. You knew the doctor, the merchant, the groceryman. If the fire whistle blew, you could call central and find out where the fire was. If the doctor was on a house call, you could call central and the operator knew where he was—at Mrs. Jones’s house, say—and if you called the Jones house, he would stop to see you on the way back to his office. This was in the little town of Dallas, Oregon.

It was a marvelous experience as a child growing up to sense the relationship to relatives, neighbors, community. Sunday school and the Methodist church were very much a part of our lives. My parents were Baptists but since there was no Baptist church in Dallas we were part of the Methodist congregation. A very important part of my early life was the fact that when I was five my mother left home to complete her education and my father and I moved in with my grandmother. I was the only child in our family.

We moved to Salem when my mother graduated from Oregon State University. She got a job teaching school just as the depression hit. My father was a blacksmith on the railroad and traveled a great deal, living in outfit cars. We united as a family in Salem and returned to the Baptist church. I was exposed to the teaching of the Bible in Sunday school, and learned the catechism pretty well—the Baptist catechism. Some people would react to my using the term “catechism.”

I remember vividly that I did not feel a part of the Baptist culture. There was a great deal of legalism in that church that created a sense of separation. I had always gone to movies; my parents felt good movies were good movies and there was nothing wrong with good movies. In high school I learned to dance and went to dances, which further isolated me.

In 1935, my parents subtly—not in any arm-twisting way—suggested that I was at the age when I should be making confession of Jesus Christ. Part of the objective my Sunday school teachers had was to lead me to some kind of confrontation with the question, “Who is Jesus Christ and what is his relation to my life?” The church had the traditional evangelistic invitation each Sunday morning and evening, and I responded in April 1935. It was a very serious thing. In my heart I knew what I was doing—that Jesus Christ was very real, and that he was my Savior. I was baptized, but I don’t recall that it made any major difference in my lifestyle or routine. It was one part of the growing-up process in that culture. I really believed. But as time went on, I had less and less interest in the church.

Then I went to Willamette University, a Methodist school in Salem, where we had to attend chapel every day. Three days a week it was a religious service. I didn’t pay much attention, except the time E. Stanley Jones came. He was a marvelous speaker and made Christ relevant to the world, India, and to us.

I also remember the day Bishop G. Bromily Oxnam came to talk about “slaughterhouse” religion (fundamentalism). I was offended by his demeaning of those very sacred things like the Blood Atonement and the Virgin Birth. In fact, I was offended whenever religion came into the conversation. I identified with the fundamentalists, and was proud of that term because we had the true faith.

When I joined the navy in 1943 and went to midshipman school, my parents gave me a little New Testament, which I still have. I had never paid much attention to it, but I began to read it because this was my first time away from home. I got up early in the morning and read the Psalms and got a sense of strength and support. Out of necessity I began to pray. I wanted to finish and get my commission. I felt as close to the Lord as I had ever felt before and for the first time in my life also felt an intimacy with the Word. I needed it badly, and the Lord was there with his faithfulness to give himself to me.

After the war, when I was dean and teaching political science at Willamette, some Christian students came and asked if they could have a room for a meeting. A man by the name of Jim Rayburn (founder of Young Life) was coming to town and they wanted him to speak on campus. The leader of the group, Doug Coe, brought Rayburn into my office. He talked about Jesus Christ like I would talk about Herbert Hoover or Calvin Coolidge or one of my political interest subjects. I thought to myself, “He does that with such ease and grace. I don’t feel defensive.”

Then Doug brought Carl Henry on campus and invited me to his lecture. By this time I had developed a disdainful attitude toward fundamentalists, but I went anyway. Doug and Carl came to my office later, and in our conversation I struggled to stay with him intellectually. I thought to myself, “This is the first time I have ever met a preacher or seminary professor who exhibited any intellectualism.” I worshiped intellectualism at the time. I was fascinated with Henry’s lecture because he talked about Jesus Christ and the Scripture in a way that gave me a whole new perspective about religion. I had come to think it was only for the masses, not the elite.

Student after student then began coming into my office and saying, “I want to tell you about something. I have found Jesus Christ.” I knew these students. They were some of the top leaders on campus. I observed their lives. Their statements to me were being lived out. This really hit me between the eyes.

In my political science courses I told my students, “Know what you believe, establish your own identity, find your own political philosophy. Don’t just inherit your philosophy or reflect your environment; define it.” One day Doug Coe put the question to me. “You know,” he said, “I think you are absolutely right. I have been struggling with trying to find my political philosophy. Tell me, what is your personal philosopy of life?”

I was absolutely stunned at the audacity of this student asking what my personal philosophy was. I said, “What do you mean, personal philosophy?”—as if to say, I am not a heathen, you know, but a sophisticated educator. He didn’t push me too hard at that point, but I knew the track he had started me on. I had to confront the faith I had accepted and taken for granted. Although I had never questioned my conversion, I had never adopted it as a way of life.

Finally, I reached a point where I knew I either had to get on or get off. I had to make some kind of commitment to Jesus Christ as Lord and Master as well as Redeemer. Salvation was not just a historic thing that happened back there once, but a continuity that had to be reflected in my own life. That commitment was my real encounter with Christ. I learned more from those Christian students than they learned from me.

I soon realized my illiteracy, my lack of maturity, and my poverty in the spiritual realm. So I began to arm myself with knowledge and read J. B. Phillips, C. S. Lewis, and D. R. Davies. Their style of writing was very provocative and specific, so I read and read and read.

I next felt the need to become part of a community of believers. I went back to the same church with a more tolerant attitude than I had when I was less active in church. Soon I was elected moderator. One day Doug Coe asked me to speak at a public Young Life meeting. I had never witnessed publicly, and I knew I couldn’t play games. I wrestled with this because it was in my own community.

That old banquet hall had mirrored posts. I can recall vividly, as if it were yesterday, the point in my speech when I had to say something more than “the Galilean” or “the Master.” When I finally used the phrase “Jesus Christ,” I felt the Devil was there. I really did. If I ever had an encounter with the Devil, it was then. That name Jesus Christ resounded off every post. I got the most piercing headache that I ever had, like hammers hitting the back of my head, pounding me from every angle—Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ. When I finished and sat down I was almost nauseated.

You have a clear reputation throughout the country as a committed Christian. Does this commitment significantly guide your work as a U.S. senator?

It guides my life. Being a senator is only one part of my Christan experience in terms of establishing my values, building relationships, being sensitive and loving to other people, and reflecting the truth of the gospel in the Incarnation. God’s grace is continually exercised through our lives to other people, and whether I am on the Senate floor or here with you, I try to live my life consistently with the gospel.

Do you encounter situations where what seems to be your duty as a senator in a pluralistic society conflicts with your Christian convictions?

Yes. The question I face is, How far can I go in applying my Christian convictions in a society that is not wholly Christian? For example, in matters of war and peace, I may be willing to risk my own life—but do I have the right to risk the lives of others?

You might come to a place where you have to choose between what you personally think is right and what is clearly the view of the majority of the people you represent.

Yes, that happens frequently, though not in terms of my Christian convictions. More often it is my political convictions that run contrary to the very constituency that I represent. That was true in the Vietnam period. At the Governors’ Conference in 1965, when polls indicated 70 to 78 percent of the people from Oregon supported President Johnson’s Vietnam policy, I cast the only negative vote. I said I would continue to fight against the war even if 99 percent of my constituency favored it. That statement was used against me in the campaign.

I belong to the Edmund Burke school of thought. We owe it to our constituents after we have engaged in debate, discussions, hearings, and all the other legislative processes, to give them the best of our judgment. Of course, it would be the height of arrogance if we stopped at that point. We are accountable to our constituents, and must defend the position we have taken. We may face the consequences in the next election, but we can’t wait until then to make ourselves accessible to them.

After I voted in the Governors’ Conference, I went from village to village and took a lot of abuse from hostile audiences. I faced people who said, “My son is fighting over there and you are undermining him.” Or, “I lost my son in that war and you are giving support and comfort to Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi.”

My own pastor was so disgusted that he practically excommunicated me. Most Christians think that when you are in Washington you can cop out on your Christian convictions, but I think the real temptation is power, not immorality.

Since politics is the art of compromise, could you give us a recent example of where you had to compromise your basic convictions in order to accept the lesser of two evils?

I have consistently supported the Hyde Amendment on abortion. But one year, when I came in as chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, we were not able to get an appropriations measure from June to December because an antiabortion amendment had been put on the appropriations bill. My strategy was to keep the Senate bill clear of any such legislation, even though it was already on the House bill. We could then go to conference with the House. So I made the motion that there not be an antiabortion amendment to the appropriations package, and pushed it through the Appropriations Committee. But we lost it on the floor. I had to compromise the procedure, but not the issue. There is a way to compromise on procedure, timing, and quantitative factors without sacrificing the principle.

Generally, what are your goals as a senator?

My goal as a senator is the same as my goal in life. Whatever role I may have, it is all part of my goal of helping build the kingdom. I am striving to help trigger a spiritual revolution. As a senator, I am dealing with political, economic, social, military, and international problems. Fundamentally, these are spiritual problems. The attempt to find a political or economic answer to a spiritual problem will never work. Therefore, in whatever role I play in life, as a senator, as a husband, as a father; in my social life, in my economic life—whatever—I have a single objective: to help create spiritual understanding.

Do you feel you have accomplished that? Do you have a sense of satisfaction in the strides you have made toward that goal?

Yes, I have great satisfaction, not in terms of achievement, but in the sense of peace of mind. I haven’t changed the world or transformed American society, and I doubt if I will. But I think there has been an impact, a voice raised when maybe other voices have not been raised, and an ability to stand in the breach, make up the hedge on occasion.

You’ve been known as a liberal Republican. One of the things that puzzles us is your vote for the Administration’s cutting back of many programs for the poor. Why do you go along with the Administration?

There is a difference between substance and perception. The perception is based on the fact that I’m chairman of the committee that has made the reduction in some of the welfare programs. The substance is that we have salvaged far more than we have reduced. I am fighting to keep programs, and have been able to retain many that otherwise would have been excised by lowering their levels of funding, levels that will be absorbed primarily by reduced overheads.

For instance, education and welfare both average a 40 percent overhead in administrative costs. With a block grant program the overhead is reduced to 20 percent. Therefore, when we reduce a program by 25 percent, we are only reducing it by about 5 percent in terms of the recipient, because 20 percent of the 25 percent would be absorbed by the change in administrative structure. In cutting some of these programs we are putting additional pressure on removing waste and abuse. I cannot tolerate that in the name of the poor or anyone else.

I also have sought to change eligibility criteria. Last year the federal government paid out over a billion dollars in Medicare payments to people who earned more than $30,000 a year. Spreading that entitlement to such a broad base of people is really weakening the whole program. By tightening the criteria we’ll have sufficient resources to help those who have desperate needs and no alternative. The appearance is that I’m trying to take away from the poor, but in effect, what I’m really doing is building strength into the programs so they reach the poor and are not wasted.

You’ve said that welfare programs may keep body and soul together but destroy the person. What are our alternatives?

I would like to get the federal government out of welfare programs entirely. The federal government has little capacity to act in a compassionate way; it creates dependencies instead. Therefore, resources should be made available through federal grants to institutions and agencies that are already in place, starting with the private ones. I would like to see welfare programs administered through the churches and synagogues and through local governments. Of course, we must maintain a federal role in criteria—such as civil rights and nondiscrimination.

You are sometimes referred to as a pacifist. Do you consider yourself a pacificist?

I consider myself a nuclear pacifist, not a pacifist in general. I’m not a unilateral disarmament person either. I am willing to risk the first step, but that has to be responded to before a second step can be taken.

I could easily say to the Soviet Union, “We have 9,000 warheads, you have 7,000 warheads. We’re willing to dismantle 500 (an arbitrary figure) of our warheads as a first step to disarm the world of nuclear weapons. What are you willing to do?” The most dangerous thing President Reagan can say to the Soviets about rejecting our proposed nuclear weapons freeze is, “You go ahead with that new submarine—go ahead with that new land-based missile, that new bomber that puts us on the brink of doom—while we build 17,000 more missiles. Then we’ll try to talk.” He is opening the door for the Russians to build a whole new generation of missiles.

To me, that’s the most dangerous thing of all. My freeze proposal would stop them before they start developing and employing these new missiles. A freeze, mutually agreed to, would be the first step. Then we could negotiate the second step.

Could we consider the problems in Central America. Do you see any way of getting justice and democracy there?

Yes, we already have a model. Costa Rica is a marvelous example of a democracy that has functioned well without an army. The resources that would have been going to the military went to establish literacy, productivity, and a free enterprise system.

Secondly, [former] President Duarte of El Salvador launched land reform, which was the key to stability. But it has gone nowhere because of opposition from wealthy landowners and the security forces. I introduced a resolution to cut off all our military aid unless the leaders will come together and work toward a political settlement. The new president could turn to all these military right-wingers and say, “Look, we’re not going to get any more arms from the United States. We’d better go to that conference table.” We could give him leverage against his own military.

You have said that when Christians organize politically they lose the real power of their Christian witness. Is this necessarily the case?

I think so. I don’t know of any profession or pursuit in life that is more seductive than politics, because it deals primarily with power.

Shouldn’t we have Christian organizations to take positions and then disseminate literature propounding them and defending them?

I don’t think so. Let me tell you my alternative: it is the living presence of Christ in the life of the believer in every facet of society. Christ calls us to be the leaven, the light, the salt. Those elements are known for their capacity to make an impact, to influence, to transform their environment. The infusion of the institutions of society with the presence of Christ, lived out through the lives of Christian people, brings the impact.

Christian political action tends to pull apart. When we try to form a new force, we’re imitating the world and its means of exercising power. We have a greater power, the power of the Holy Spirit working within us, expressed in love, compassion, and the other fruit of the Spirit. Why should we reduce that power, thinking we’re enhancing it through organizations? At times we need to mobilize ourselves, to speak out as bodies. But when we say, in effect, that if we can get enough people out to vote and get enough Christians elected to public office we’ll have the levers of power, we are reflecting a cultural, not a spiritual, bond.

In view of your alternative to organized Christian political action, how would you attack such areas as pornography and abortion?

There was never a greater political animal in my lifetime than Lyndon B. Johnson. He wanted to be president of the United States more than anything else in the world. He sought political power; he loved it. And he was very, very capable in the political realm. What brought him down? There was no organization as such that said, “President Johnson, we don’t like this war any longer.”

But there was a peace movement. It really wasn’t much, and it turned more people off than it turned on to the issue. No matter. Lyndon Johnson got the mood of the public. He got the communication just as clearly as if it had been written to him in brilliant lights: “Johnson, we’ve left you; our opinion as a public is now totally against you.” That literally drove him out of the White House. It wasn’t an organization. It wasn’t the Republican party—the Republican party didn’t have enough sinews to drive a person out of city hall, let alone the White House at that particular moment.

I’m using this to illustrate the fact that if there’s enough sentiment, opinion, and feelings against these evils, things will change. Pornography exists today because the people are tolerating it and aren’t willing to challenge it. How did they get the prostitues off Logan Circle in Washington? It happened when some of the neighbors got so fed up that they took pictures of people in cars stopping and making deals.

These social evils exist largely because people tolerate and accept them. Even good churchmen who profess to be concerned expect solutions to come from the top. They want an imposed moral or ethical regulatory action. But effective changes come only from within.

Is there any way out of the legislative impasse on abortion?

I don’t think there’s going to be any action taken via the Constitution, even though I introduced the first constitutional amendment on abortion. I’m introducing a bill in the Senate, and Congressman Hyde is introducing it in the House. It prohibits the use of federal funding to perform abortions unless the life of the mother is at stake.

Is there any way to help Christian schools financially without atthe same time bringing government control?

Once you accept a favor or something that is to your benefit—no matter what it is—you have immediately put yourself under obligation. You can’t ask for tax exemption or tax credit on one hand without expecting the government eventually to set certain controls and regulations on the other. I’m fiercely independent in many ways, but I’m especially for private schools. We have to be very wise and cautious about accepting favors from government. I feel very strongly that there is a role for Christian schools, but I do not support tax credits for elementary and secondary education.

I do support tax credits within restricted income areas for higher education. I delineate between the two because one is compulsory and one is not. I strongly support public schools, as well as private; I believe in the dual system. I want to see the independence of Christian schools, but if they come here with their hands out to the federal government, and they begin to accept favors, with that comes greater possibilities of intervention.

You are known as a political leader, but you also are a spiritual leader. What advice do you have for spiritual leaders?

Any leadership role carries with it certain dangers as well as advantages. Concerning the dangers, leaders have a tendency to think that they are now in a position to give out, that such giving comes from an unlimited supply. They reach the point where they don’t realize the need for intake, and so they tend to get fatigued—mentally, intellectually, spiritually, or physically. Our political society teaches us that to confess need is a weakness. But a leader must recognize that need to be vulnerable.

On top of the hill the wind blows harder, and we are more vulnerable to that wind in all directions. In church work you can be so busy for Christ that you take no time to be with Christ. You can be so busy telling people how to study the Bible that you do not take time to take in the Word for your own needs.

Frequently a leader becomes possessive of the role—it’s his position, his office, his title. Leaders must contribute something out of their experience to help others assume leadership roles. There is also the need to evangelize in whatever you’re doing. I use that term broadly. We fall into such a routine that we assume everyone has the same interests or priorities. We grow less sensitive to other people because we’re so committed to our own causes or organizations. We have to look beyond our own walls and our own little group consciousness and see what we can do to share, to make a better world, and to help other people.

One of the most disastrous fates that could befall a leader is to become the embodiment of a cause or issue. When the ego and the issue are so fused that one is no longer able to delineate between them, honest disagreement is taken as a personal attack, and that in turn produces counterattack and ultimately ruptures the relationship. That comes basically out of ego.

When do you think you’ll come to a decison about seeking another term?

I’ll put it off as long as I can. But let me be frank: reelection is an issue that all politicians play to a certain advantage. When I made my commitment to Christ, I said in effect, “Christ, I want to live my life for you, I want to be in your will.” From the standpoint of that commitment, I don’t know what the future holds for me, but I do know it’s the Lord’s will that I’m here now. I’m in a business where you are constantly tempted to think ahead to the next term, to wonder what impact your vote is going to have on your reelection. It’s easy to succumb to this political culture that says you have to commit yourself for 30 or 40 years because if you don’t, the world will fall apart.

William Jennings Bryan went around telling people that the Lord had called him to be president of the United States. But the Lord wasn’t a smart enough politician to get the voters to affirm that. When I let myself get into that kind of situation, I become totally imprisoned to my career and all I’m saying is, “Lord, I have a blueprint here. Will you ratify it and make it your will for my life?”

I’m totally liberated; I have no obligation to the political future because I have only run and been elected to this term. I don’t want my staff even to think of what impact my votes will have on the next election. Because I am liberated I can make the best judgment call based on facts, conferences, and discussions. Even if 150 percent of the people are opposed to it, I still have the freedom to make it. It’s the most exhilarating way to play politics.

One of my colleagues said to me, “There’s a correct vote and there’s a political vote. Mark, I just want you to know I’ve been making the political vote because I’m running for reelection.” That’s imprisonment. I pray for the integrity, justice, and courage to vote the correct vote, not the political vote. It’s a reckless style of politics, but it’s the only style I know.

Are you modeling someone in this regard?

No, I learned it in the political science classroom. You can’t stand before a group of students for seven years and play games with them. They sense it immediately. When they ask a question they want an answer, not a lot of double talk.

When I came to know the Lord, I sensed a liberation from enslavement to intellectualism, to cultural acceptability, to being socially debonair. Having sensed my liberation from those false gods, why should I imprison myself again in any area of life?