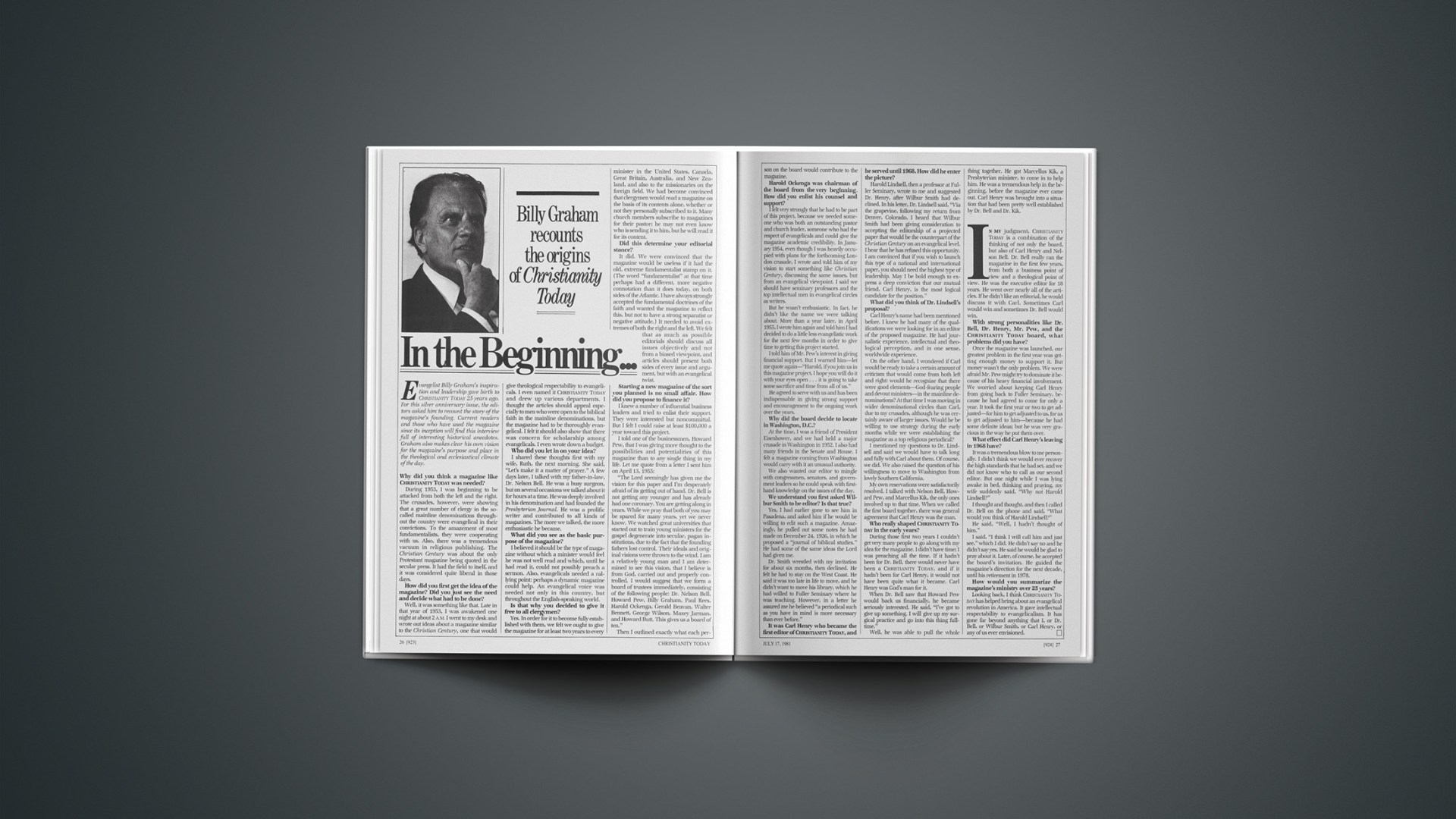

Billy Graham recounts the origins of Christianity Today

Evangelist Billy Graham’s inspiration and leadership gave birth to CHRISTIANITY TODAY 25 years ago. For this silver anniversary issue, the editors asked him to recount the story of the magazine’s founding. Current readers and those who have used the magazine since its inception will find this interview full of interesting historical anecdotes. Graham also makes clear his own vision for the magazine’s purpose and place in the theological and ecclesiastical climate of the day.

Why did you think a magazine like CHRISTIANITY TODAY was needed?

During 1953, I was beginning to be attacked from both the left and the right. The crusades, however, were showing that a great number of clergy in the so-called mainline denominations throughout the country were evangelical in their convictions. To the amazement of most fundamentalists, they were cooperating with us. Also, there was a tremendous vacuum in religious publishing. The Christian Century was about the only Protestant magazine being quoted in the secular press. It had the field to itself, and it was considered quite liberal in those days.

How did you first get the idea of the magazine? Did you just see the need and decide what had to be done?

Well, it was something like that. Late in that year of 1953, I was awakened one night at about 2 A.M. I went to my desk and wrote out ideas about a magazine similar to the Christian Century, one that would give theological respectability to evangelicals. I even named it CHRISTIANITY TODAY and drew up various departments. I thought the articles should appeal especially to men who were open to the biblical faith in the mainline denominations, but the magazine had to be thoroughly evangelical. I felt it should also show that there was concern for scholarship among evangelicals. I even wrote down a budget.

Who did you let in on your idea?

I shared these thoughts first with my wife, Ruth, the next morning. She said, “Let’s make it a matter of prayer.” A few days later, I talked with my father-in-law, Dr. Nelson Bell. He was a busy surgeon, but on several occasions we talked about it for hours at a time. He was deeply involved in his denomination and had founded the Presbyterian Journal. He was a prolific writer and contributed to all kinds of magazines. The more we talked, the more enthusiastic he became.

What did you see as the basic purpose of the magazine?

I believed it should be the type of magazine without which a minister would feel he was not well read and which, until he had read it, could not possibly preach a sermon. Also, evangelicals needed a rallying point: perhaps a dynamic magazine could help. An evangelical voice was needed not only in this country, but throughout the English-speaking world.

Is that why you decided to give it free to all clergymen?

Yes. In order for it to become fully established with them, we felt we ought to give the magazine for at least two years to every minister in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, and also to the missionaries on the foreign field. We had become convinced that clergymen would read a magazine on the basis of its contents alone, whether or not they personally subscribed to it. Many church members subscribe to magazines for their pastor; he may not even know who is sending it to him, but he will read it for its content.

Did this determine your editorial stance?

It did. We were convinced that the magazine would be useless if it had the old, extreme fundamentalist stamp on it. (The word “fundamentalist” at that time perhaps had a different, more negative connotation than it does today, on both sides of the Atlantic. I have always strongly accepted the fundamental doctrines of the faith and wanted the magazine to reflect this, but not to have a strong separatist or negative attitude.) It needed to avoid extremes of both the right and the left. We felt that as much as possible editorials should discuss all issues objectively and not from a biased viewpoint, and articles should present both sides of every issue and argument, but with an evangelical twist.

Starting a new magazine of the sort you planned is no small affair. How did you propose to finance it?

I knew a number of influential business leaders and tried to enlist their support. They were interested but noncommittal. But I felt I could raise at least $100,000 a year toward this project.

I told one of the businessmen, Howard Pew, that I was giving more thought to the possibilities and potentialities of this magazine than to any single thing in my life. Let me quote from a letter I sent him on April 13, 1955:

“The Lord seemingly has given me the vision for this paper and I’m desperately afraid of its getting out of hand. Dr. Bell is not getting any younger and has already had one coronary. You are getting along in years. While we pray that both of you may be spared for many years, yet we never know. We watched great universities that started out to train young ministers for the gospel degenerate into secular, pagan institutions, due to the fact that the founding fathers lost control. Their ideals and original visions were thrown to the wind. I am a relatively young man and I am determined to see this vision, that I believe is from God, carried out and properly controlled. I would suggest that we form a board of trustees immediately, consisting of the following people: Dr. Nelson Bell, Howard Pew, Billy Graham, Paul Rees, Harold Ockenga, Gerald Beavan, Walter Bennett, George Wilson, Maxey Jarman, and Howard Butt. This gives us a board of ten.”

Then I outlined exactly what each person on the board would contribute to the magazine.

Harold Ockenga was chairman of the board from the very beginning. How did you enlist his counsel and support?

I felt very strongly that he had to be part of this project, because we needed someone who was both an outstanding pastor and church leader, someone who had the respect of evangelicals and could give the magazine academic credibility. In January 1954, even though I was heavily occupied with plans for the forthcoming London crusade, I wrote and told him of my vision to start something like Christian Century, discussing the same issues, but from an evangelical viewpoint. I said we should have seminary professors and the top intellectual men in evangelical circles as writers.

But he wasn’t enthusiastic. In fact, he didn’t like the name we were talking about. More than a year later, in April 1955, I wrote him again and told him I had decided to do a little less evangelistic work for the next few months in order to give time to getting this project started.

I told him of Mr. Pew’s interest in giving financial support. But I warned him—let me quote again—“Harold, if you join us in this magazine project, I hope you will do it with your eyes open … it is going to take some sacrifice and time from all of us.”

He agreed to serve with us and has been indispensable in giving strong support and encouragement to the ongoing work over the years.

Why did the board decide to locate in Washington, D.C.?

At the time, I was a friend of President Eisenhower, and we had held a major crusade in Washington in 1952. I also had many friends in the Senate and House. I felt a magazine coming from Washington would carry with it an unusual authority.

We also wanted our editor to mingle with congressmen, senators, and government leaders so he could speak with firsthand knowledge on the issues of the day.

We understand you first asked Wilbur Smith to be editor? Is that true?

Yes, I had earlier gone to see him in Pasadena, and asked him if he would be willing to edit such a magazine. Amazingly, he pulled out some notes he had made on December 24, 1926, in which he proposed a “journal of biblical studies.” He had some of the same ideas the Lord had given me.

Dr. Smith wrestled with my invitation for about six months, then declined. He felt he had to stay on the West Coast. He said it was too late in life to move, and he didn’t want to move his library, which he had willed to Fuller Seminary where he was teaching. However, in a letter he assured me he believed “a periodical such as you have in mind is more necessary than ever before.”

It was Carl Henry who became the first editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, and he served until 1968. How did he enter the picture?

Harold Lindsell, then a professor at Fuller Seminary, wrote to me and suggested Dr. Henry, after Wilbur Smith had declined. In his letter, Dr. Lindsell said, “Via the grapevine, following my return from Denver, Colorado, I heard that Wilbur Smith had been giving consideration to accepting the editorship of a projected paper that would be the counterpart of the Christian Century on an evangelical level. I hear that he has refused this opportunity. I am convinced that if you wish to launch this type of a national and international paper, you should need the highest type of leadership. May I be bold enough to express a deep conviction that our mutual friend, Carl Henry, is the most logical candidate for the position.”

What did you think of Dr. Lindsell’s proposal?

Carl Henry’s name had been mentioned before. I knew he had many of the qualifications we were looking for in an editor of the proposed magazine. He had journalistic experience, intellectual and theological perception, and in one sense, worldwide experience.

On the other hand, I wondered if Carl would be ready to take a certain amount of criticism that would come from both left and right: would he recognize that there were good elements—God-fearing people and devout ministers—in the mainline denominations? At that time I was moving in wider denominational circles than Carl, due to my crusades, although he was certainly aware of larger issues. Would he be willing to use strategy during the early months while we were establishing the magazine as a top religious periodical?

I mentioned my questions to Dr. Lindsell and said we would have to talk long and fully with Carl about them. Of course, we did. We also raised the question of his willingness to move to Washington from lovely Southern California.

My own reservations were satisfactorily resolved. I talked with Nelson Bell, Howard Pew, and Marcellus Kik, the only ones involved up to that time. When we called the first board together, there was general agreement that Carl Henry was the man.

Who really shaped CHRISTIANITY TODAY in the early years?

During those first two years I couldn’t get very many people to go along with my idea for the magazine. I didn’t have time; I was preaching all the time. If it hadn’t been for Dr. Bell, there would never have been a CHRISTIANITY TODAY, and if it hadn’t been for Carl Henry, it would not have been quite what it became. Carl Henry was God’s man for it.

When Dr. Bell saw that Howard Pew would back us financially, he became seriously interested. He said, “I’ve got to give up something. I will give up my surgical practice and go into this thing full-time.”

Well, he was able to pull the whole thing together. He got Marcellus Kik, a Presbyterian minister, to come in to help him. He was a tremendous help in the beginning, before the magazine ever came out. Carl Henry was brought into a situation that had been pretty well established by Dr. Bell and Dr. Kik.

In my judgment, CHRISTIANITY TODAY is a combination of the thinking of not only the board, but also of Carl Henry and Nelson Bell. Dr. Bell really ran the magazine in the first few years, from both a business point of view and a theological point of view. He was the executive editor for 18 years. He went over nearly all of the articles. If he didn’t like an editorial, he would discuss it with Carl. Sometimes Carl would win and sometimes Dr. Bell would win.

With strong personalities like Dr. Bell, Dr. Henry, Mr. Pew, and the CHRISTIANITY TODAY board, what problems did you have?

Once the magazine was launched, our greatest problem in the first year was getting enough money to support it. But money wasn’t the only problem. We were afraid Mr. Pew might try to dominate it because of his heavy financial involvement. We worried about keeping Carl Henry from going back to Fuller Seminary, because he had agreed to come for only a year. It took the first year or two to get adjusted—for him to get adjusted to us, for us to get adjusted to him—because he had some definite ideas; but he was very gracious in the way he put them over.

What effect did Carl Henry’s leaving in 1968 have?

It was a tremendous blow to me personally. I didn’t think we would ever recover the high standards that he had set, and we did not know who to call as our second editor. But one night while I was lying awake in bed, thinking and praying, my wife suddenly said, “Why not Harold Lindsell?”

I thought and thought, and then I called Dr. Bell on the phone and said, “What would you think of Harold Lindsell?”

He said, “Well, I hadn’t thought of him.”

I said, “I think I will call him and just see,” which I did. He didn’t say no and he didn’t say yes. He said he would be glad to pray about it. Later, of course, he accepted the board’s invitation. He guided the magazine’s direction for the next decade, until his retirement in 1978.

How would you summarize the magazine’s ministry over 25 years?

Looking back, I think CHRISTIANITY TODAY has helped bring about an evangelical revolution in America. It gave intellectual respectability to evangelicalism. It has gone far beyond anything that I, or Dr. Bell, or Wilbur Smith, or Carl Henry, or any of us ever envisioned.