Though Tiananmen translates as “The Gate of Heavenly Peace,” the Beijing city square is known for something utterly destructive: the June 4, 1989, massacre where Chinese troops fired on nonviolent student demonstrators, killing thousands—deaths that the government still has not publicly acknowledged.

The historic event came amid a national movement for democracy and freedom and set off a spiritual awakening for the Chinese, according to sociologist Yang Fenggang.

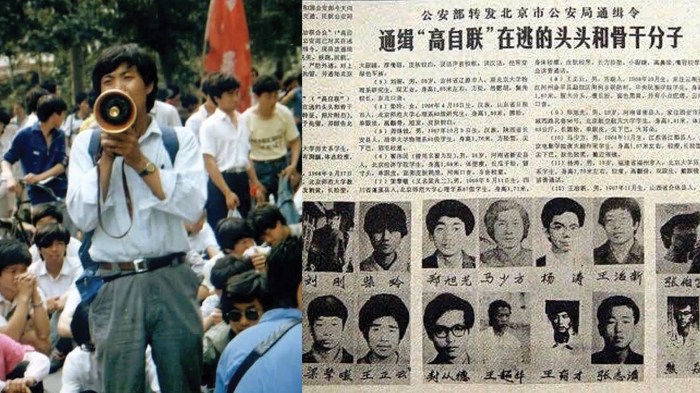

Among the young activists who stood in Tiananmen Square 30 years ago were Zhang Boli and Zhou Fengsuo. Both landed on China’s most-wanted list, were imprisoned, fled the country, and live in exile. The pair are also among at least 4 of the 21 most-wanted student activists to come to faith in Christ, with Zhang serving as the pastor of Harvest Chinese Christian Church, a multisite church with locations around the world, and Zhou leading Humanitarian China, which advocates on behalf of political prisoners in his homeland.

“Of the Tiananmen Square student leaders who have converted to Christianity, they tend to see evangelism as the priority,” said Yang, director of the Center on Religion and Chinese Society at Purdue University. “A priority of their social activism is humanitarian aid to people in China or exiled in the US, including political dissidents, human rights lawyers, and Christian leaders who have been persecuted for their leadership in the house churches.”

Zhang and Zhou’s historic involvement gives them a unique perspective on the Communist government’s crackdown on China’s growing house church movement, whose leaders were inspired by the Tiananmen activism decades ago.

“We may forget that there was this Tiananmen moment of hope, but for the future of China, it’s so important to remember,” Zhou said. “Commemorating is a way of resistance.”

This month’s 30th anniversary of the massacre offers the global church a chance to consider the spiritual significance of the ongoing fight for basic freedoms and human rights.

“With theological reflections, we can strive to be better prepared for future social activism and social transformation,” Yang said. “Without theological depth, social and political movements will only bring more chaos, violence, and bloodshed.”

Yang—who projects the country will be home to more Christians than any other by 2030—wants to see evangelicals partner more closely with the house churches operating outside of China’s government-sanctioned Three-Self Patriotic Movement.

Zhang and Zhou (the former responding through a translator) talked to Jenny McGill about how their Christian faith spurs their fight for freedom. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Take us back to Tiananmen Square. What happened in your life that led you to participate, and what did you hope the outcome would be?

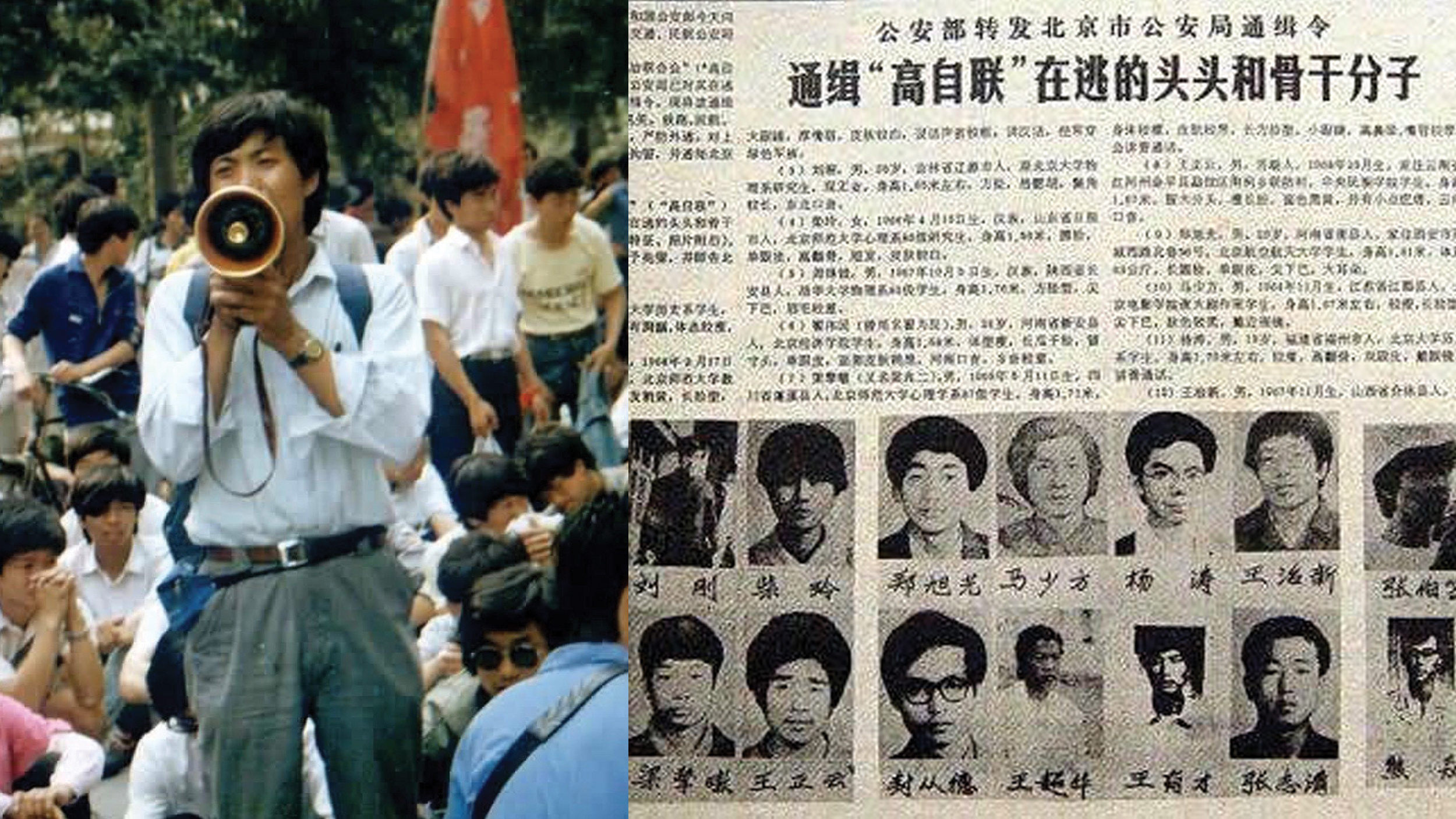

ZHANG: I was a writer and wanted to go to Tiananmen Square to record the events and turn it into a book. I was also a student at Peking University and joined the other students who were going. I was a speaker at the square and led others in a hunger strike.

We wanted to commemorate [former general secretary of the Communist Party] Hu Yaobang’s death. The government thought we were being unruly, and we disagreed with this depiction. We wanted democracy, freedom, and human rights respected.

ZHOU: It was a gradual process. I started as a participant and went with my friends in the same dormitory. We were the first ones to openly commemorate Hu Yaobang, the party leader who lost his post for being sympathetic with students a few years before. When he died, that triggered the whole event, the protests.

China was much more open at that time. [The Chinese] were looking out to the Western world for ideas, new technology, people, everything. There were broad discussions in public. I really loved to read the history of America. I was inspired when I was learning English and reading the Declaration of Independence and the story of Abraham Lincoln. In that generation, we were very much in love with the idea of freedom and democracy for China. Our two most immediate demands were freedom of the press and the disclosure of the assets of the government officials. … These were very popular, gaining support of the Chinese people very quickly. That’s why it spread out like fire into the whole society all over China.

Courtesy of Zhang Boli

Courtesy of Zhang BoliWhat happened to you after the protest?

ZHANG: Of those participating in Tiananmen, they began to arrest so many, so I fled to the Soviet Union. The KGB soon arrested me because I had entered the country illegally. I was in prison for two months before they returned me to China. I was able to escape at the border of China and the Soviet Union. I hid from the Chinese government for two years, staying in Heilongjiang in the northeast of China and later traveling south.

In 1991, I was smuggled onto a boat to Hong Kong, went to the US Embassy, and applied for asylum, which was granted that day. [Other dissidents escaped from China through Operation Yellowbird, deftly organized by a group of Hong Kong sympathizers. One of those sympathizers was pastor Chu Yiu-ming, among those arrested and convicted for their part in the Hong Kong Occupy Central and Umbrella Movement of 2014.]

ZHOU: Because I was a member of the leading student organization at Tsinghua University, I was No. 5 on China’s most-wanted list of 21 student leaders. It was very shocking to everyone, including me, to become a leader of the movement. To me, the movement was mostly spontaneous, an outcry from people’s hearts.

I was arrested ten days after the massacre. Let me correct the record here. My sister and brother-in-law never intended to turn me in—they were trying to help me. The government changed the story [to say] they had turned me in. I was detained for the year without trial in the top security prison in China, Qincheng, famous for holding government officials.

I was released at the one-year anniversary of Tiananmen along with a lot of people, mostly because of pressure from the US. At the time, every June, Congress had to approve China’s “most-favored nation” status. I was sent to a re-education program to change my thinking in one of the poorest rural places [Yangyuan, Hebei province]. The condition was if I went through the three-year program, I would be able to resume my studies. I rejected that after a year. I never completed my bachelor’s degree. My school was trying to help me and gave me an associate’s degree. Being banned from leaving China for a couple of years, I came to the US in 1995.

Photos Courtesy of Zhang Boli

Photos Courtesy of Zhang BoliHow did you come to Christian faith?

ZHANG: I was raised with no God, no religion, nothing—well, other than believing in the Communist Party. When I was hiding out in Heilongjiang for those two years, I met an old lady farmer who introduced me to Christianity and talked with me about Jesus. She had the Gospel of John, not even the full Bible, which had been hand copied onto paper. She was illiterate actually, so she gave it to me to read aloud and then she would explain it to me. In about a year, I became a Christian.

I was brought up in an atheist educational system, and after reading John’s Gospel I realized that every person needs a god, something to believe in. They can’t save themselves. I realized that my involvement in Tiananmen Square was no coincidence; I was being influenced and guided by God. Tiananmen led me to escape, my imprisonment, and ultimately to meet this old woman. I think this was all arranged.

ZHOU: I read the Bible in high school, but I didn’t understand it. Later, after prison while I was in China, I read the Bible, and there were people trying to bring me to faith. In June 1995, my first Tiananmen anniversary in the United States, I was looking for a place to commemorate, so I walked into a church in San Antonio. That left a big impression on me. I was welcomed. I felt a connection and relief from the pain while I was at the church. It was the first time after the massacre for me to think, “Is there a God? Why would God allow Tiananmen?” The values we believed in China at that time were based on patriotism, love of country, but the government, the country, betrayed us. Where is this value of our life? This was the turning point.

After I moved to Chicago for business school, this brother from the church in Texas kept writing to me, saying that he was praying for me. I remember him asking me every time: “Are you ready to believe in Jesus?” I just tried to dodge the question. After business school, I thought if I could find a job, I would believe in God. But when I found a pretty good job at a Wall Street firm [Bear Stearns], I forgot all about that, thinking this is all my own achievement.

Later, my life began to stabilize, and I could feel this void in my heart. I was always following what was happening in China, the Tiananmen movement, the people who were still in prison, and China’s political situation. As the years dragged on, it seemed hopeless. I was filled with hatred toward Communists because of the injustice, of what they did to us, to me. I couldn’t see that it could change. I felt powerless. That’s the other reason I turned to God. In 2003, we went to a church. When the pastor gave a very good sermon and afterward, he asked, “Are you ready to believe?” I raised my hand. That moment I felt a big burden coming off my shoulders.

How has your faith changed how you view what happened at Tiananmen?

ZHANG: I feel like God used what happened in 1989 to help us recognize what’s going on in China. If the Tiananmen massacre had not occurred, for the Chinese people, the Communist Party would have been their god. The event helped people realize that the Communist Party was a ghost.

ZHOU: To me, I think the most important change is the hope that we have through God. What we couldn’t get in this world, we have from God. It’s so comforting, and it gives me strength to face all the difficulties and challenges in human rights activism. At the same time that I became a Christian, I began to donate money to help political prisoners in China. Quickly, that activity evolved into Humanitarian China, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting human rights and providing for families of political prisoners and persecuted Christians.

Has your faith changed your perspective on social activism? How do they relate?

ZHANG: They really go together. Freedom, human rights—they come from God. The democracy movement wasn’t just about politics alone; it was also about lifestyle. People realize that Jesus and freedom, they go together, and I hope that this is the future for the Chinese people. For Chinese people to achieve democracy, they need to have some kind of religious belief. They need to have choices in life. They should have freedom in their thinking and lifestyle.

ZHOU: Fundamentally, I think it’s the same now, my faith as a Christian and my activism. For me, they’re an integral part of my life. My inspiration came from reading the Bible, from prayer, from following examples of believers ahead of me. My activism is the way of following Jesus: to care for the persecuted and the underprivileged and to bring love and peace when there’s suppression by the government.

Humanitarian China is not a Christian ministry, but it has a very deep Christian connection and motivation. We are intimately connected to house churches in China to give them any support they need and gain awareness of their situations. There’s a particular connection between the Tiananmen movement and the Christian church today in China. Many of the leaders in the house church community were influenced by the Tiananmen movement. Some of them were protestors themselves, and some were the second wave, like [imprisoned house church] pastor Wang Yi who was in high school then. This was his inspiration and formed a basic foundation for his worldview. This happened for lots of people like Yu Jie, the famous writer.

How do you view the state of the church in China today?

ZHANG: Before 1989, China had about 5 million Christians. Estimates now range from 50 million to 80 million. The Communist government seeks to limit the development and growth of Christianity in China, but I don’t think this is working very well. God is at work.

In the Henan province, the government has torn down numerous churches. In Wenzhou, a city in China’s eastern Zhejiang province, also. Attending activities of these churches, you could be arrested or imprisoned. Your children could be punished or restricted. You could be fired from your company if the government contacts them about your involvement in Christianity. The government certainly doesn’t approve of nationals of other countries bringing in Christian materials, and if you get caught, they can hinder your return to China. This has actually become more serious over the last year, restricting the practice of Christianity more than they ever have before.

ZHOU: The growth of Chinese churches, particularly house churches, is one of the most fundamental changes and important features in Chinese society in the last 30 years, its impact still to be seen and to be understood.

There’s a significant portion of Chinese who are Christians [almost 8 percent, according to Operation World]. House churches are probably the only form of an independent organization not under government control. For this totalitarian regime, this is a very strong challenge to its control. That’s why they are the target of the persecution.

Also, most of the house churches, even though they were under persecution, were not socially active. To protect themselves, most of them tried to stay away from attention. Some, like Early Rain Covenant Church and Shouwang and Zion churches in Beijing, are under attack now and need a lot of help. In the end, persecution in the past has never succeeded in repressing people’s faith. The struggle for the freedom to believe is very important in Chinese people’s pursuit of freedom against the Communist Party.

Photo Courtesy of Zhou FEngsuo

Photo Courtesy of Zhou FEngsuoHow can North American churches best serve the persecuted religious minorities in China?

ZHANG: The first way is to share physical materials like Bibles with them. If the church in China is being persecuted by the government and they are not receiving support and encouragement from the US church, they could lose morale. I’m referring to all churches in North America, not just Chinese Christian churches. The churches in the US should use their religious freedom to help give a voice to Christians in other countries who might not have those freedoms, especially in China. American churches have the moral duty to assist those persecuted and to pressure the Chinese government to allow its citizens religious freedom.

ZHOU: Most of the Chinese churches [in the US] are too quiet on the issues. There’s not enough of a voice for the persecuted church in China. International support from Western society, in particular from churches, is very important and encouraging to Chinese believers. Humanitarian China started because we were trying to fill a vacuum…. After the Tiananmen massacre, politically, China has been going backward. It’s pretty clear that it cannot coexist with freedom and democracy. The world needs to be alerted to this.

China is so strong now with its economic reach and technological power that it’s a threat to everyone. We have to confront it. In the way it treats its own people, it cannot be a force of peace and prosperity…. On the other hand, the Christian church is definitely a light to many people. The value and acts of the house churches are providing alternatives to the totalitarian society.

Jenny McGill is a pastor’s wife and a dean at Indiana Wesleyan University. She holds a PhD from King’s College London, and her books include The Self Examined and Walk with Me: Learning to Love and Follow Jesus, a discipleship resource for women.

Learn something new from this interview? Did we miss something? Let us know here.