“When there is no authority in religion or in politics, men are soon frightened by the limitless independence with which they are faced. They are worried and worn out by the constant restlessness of everything.” Alexis de Tocqueville observed this about 19th-century Americans and their budding instincts on freedom and religion. But he could just as well have been describing today’s young adults. In a new life phase that sociologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett labeled emerging adulthood, Americans ages 18-29 enjoy more options for work, marriage, and location than perhaps any previous generation. They are also one of the most self-focused, confused, and anxious age groups, led into an “adultolescence” that prevents a majority from committing to people and institutions.

Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults

Oxford University Press

368 pages

$16.05

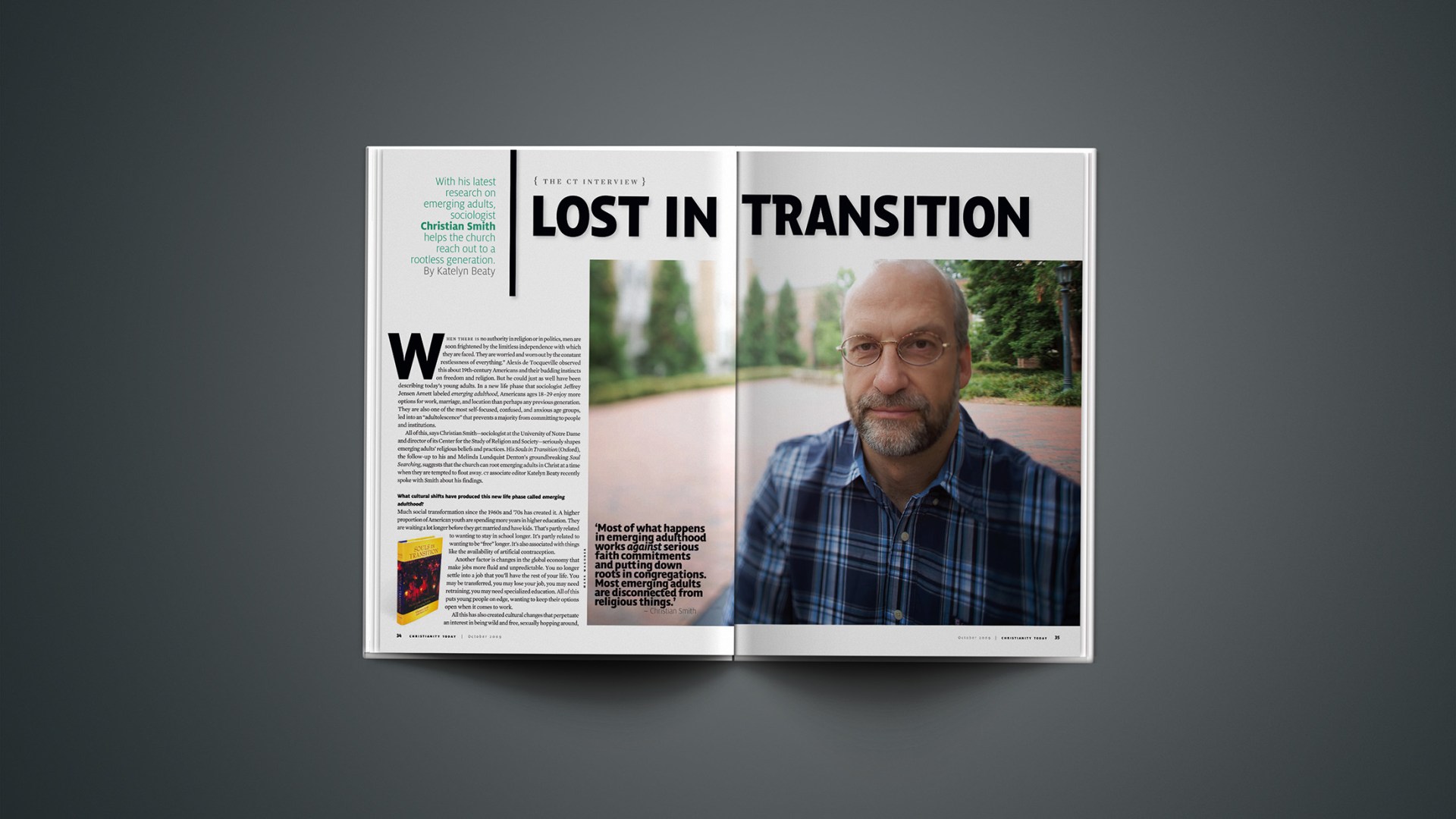

All of this, says Christian Smith—sociologist at the University of Notre Dame and director of its Center for the Study of Religion and Society—seriously shapes emerging adult’s religious beliefs and practices. His Souls in Transition (Oxford), the follow-up to his and Melinda Lundquist Denton’s groundbreaking Soul Searching, suggests that the church can root emerging adults in Christ at a time when they are tempted to float away. CT associate editor Katelyn Beaty recently spoke with Smith about his findings.

What cultural shifts have produced this new life phase called emerging adulthood?

Much social transformation since the 1960s and ’70s has created it. A higher proportion of American youth are spending more years in higher education. They are waiting a lot longer before they get married and have kids. That’s partly related to wanting to stay in school longer. It’s partly related to wanting to be “free” longer. It’s also associated with things like the availability of artificial contraception.

Another factor is changes in the global economy that make jobs more fluid and unpredictable. You no longer settle into a job that you’ll have the rest of your life. You may be transferred, you may lose your job, you may need retraining, you may need specialized education. All of this puts young people on edge, wanting to keep their options open when it comes to work.

All this has also created cultural changes that perpetuate an interest in being wild and free, sexually hopping around, for a time. As they exit the teenage years, young people basically understand they have up to 12 years before having a family and settling into their “real job.” And those are very important years.

How do all these transitions affect emerging adults’ religious attitudes?

Most of what happens in emerging adulthood works against serious faith commitments and putting down roots in congregations. Most emerging adults are disconnected from religious institutions and practices. Geographic mobility, social mobility, wanting to have options, thinking this is the time to be crazy and free in ways most religious traditions would frown upon, wanting an identity different from the family of origin—all of these factors reduce serious faith commitments.

For some emerging adults, the chaos helps them find that religion is an extremely helpful antidote. But that’s after they have been through many difficulties. And only some look to faith to provide stability; most do not go there in the first place.

All that said, there is a significant minority of emerging adults who are raised in seriously religious families who continue on with that. It’s not a story of consistent decline. But overall the culture of emerging adulthood puts many pressures on faith practices that are undermining or depressing.

What are the traits of religious American teenagers who retain a high faith commitment as emerging adults?

The most important factor is parents. For better or worse, parents are tremendously important in shaping their children’s faith trajectories. That’s the story that came out in Soul Searching. It’s also the story that comes out here.

Another factor is youth having established devotional lives—that is, praying, reading Scripture—during the teenage years. Those who do so as teenagers are much more likely than those who don’t to continue doing so into emerging adulthood. In some cases, having other adults in a congregation who you have relationships with, and who are supportive and provide modeling, also matters.

Some readers are going to be disappointed that going on mission trips doesn’t appear to amount to a hill of beans, at least for emerging adults as a whole. For some it’s important, but not for most. But again, we emphasize above everything else the role of parents, not just in telling kids about faith but also in modeling it.

Your research seems to cast doubt on previous studies that concluded higher education corrodes religious belief.

Yes. It’s not that the previous studies were wrong. It’s that the world is actually changing. If anything, college is no different in terms of the faith corrosion outcomes on youth. It may even strengthen the faith of some. We think this is partly about a growing number of evangelical faculty at secular colleges. Another factor is the increasing presence and legitimacy of campus religious groups and ministries [InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Campus Crusade] that provide support systems—not just fellowship, but also intellectual engagement that may have been lacking in past decades.

The culture has also changed: “spirituality” is more acceptable now than in past decades. Most faculty know you cannot say stupidly anti-religious things in the classroom and get away with it.

Lost in transition

It’s not that parents should not worry when their kids go to college. But there are factors in place now so that faith communities have figured out ways to support their college-age youth.

With Soul Searching, you found that most U.S. teens are Moralistic Therapeutic Deists (MTD). They believe in a benevolent God unattached to a particular tradition who is there mostly to help with personal problems. Are emerging adults still MTDS?

Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is still the de facto practiced religious faith, but it becomes a little more complicated for emerging adults. They have more life experience, so some of them are starting to ask, “Does MTD really work? Isn’t life more complicated than this?” MTD is easier to believe and practice when you are in high school.

There is also a much larger segment of emerging adults than of teenagers that is outrightly hostile to religion. Some who previously were MTDS have become anti-religious. That said, the center of gravity among emerging adults is definitely MTD. Most emerging adults view religion as training in becoming a good person. And they think they are basically good people. To not be a good person, you have to be a horrible person. Therefore, everything’s fine.

Where are all the adult Christians in emerging adults’ lives? Might they be able to positively influence them as they face intense change and instability?

This is one concern of mine. Teenagers, we argued in Soul Searching, are structurally disconnected from the adult world. We think that emerging adults are also structurally disconnected from older adults who could be their mentors. The emerging adult world is self-enclosed. Older adults tend to be bosses with whom you have limited interaction, or professors with whom you are on performance terms. Even in some of the best churches, if an emerging adult happens to stay for Sunday school, it’s very likely to be in a post-college-age group. It’s hard for them to meet somebody who is 39 or 62 to get to know them and say, “Here’s what I’ve learned in life.”

Again, we are sociologists, not church consultants. But in terms of the implications of our work for churches, the two key words are engagement and relationships. It can’t just be programs or classes or handing them over to the youth pastor. Real change happens in relationships, and that takes active engagement.

What are other ways churches can connect with emerging adults in these unsettled years?

To connect with emerging adults is going to take more creativity and initiative than I see at the moment. Part of it goes back to the first issue, which is simply recognizing, “Oh, there is this new phase in life.” It’s not that we have adolescents and then we have adults. This long and culturally important time in the life course has developed fairly recently, historically speaking, and it needs to be grappled with. What does this mean? And how does it figure into faith formation?

Churches that are near colleges and universities can certainly make better attempts to connect with students. Even if parents can’t stay in touch with where their kids are spiritually, they can at least support on-campus Christian groups. And adults in congregations where teenagers grew up can make efforts to stay in touch into the future.

Many churches are set up to cater to married couples with children. This is a well-known fact. And they may try to do something for teens and emerging adults. But trying to be more conscious and intentional about the language they use, the programs they offer, so those who are not married and don’t have children are not sidelined—that’s a start. But it probably will require more creative thinking about context—I don’t even want to say programs—but ways to form communities and places where people can connect and work out common interests beyond the standard worship service and Sunday school.

More generally, churches need to realize that American demographics and the American family are changing. If they are set up to minister primarily to intact nuclear families, there are whole, growing segments of the population they are not hitting. It requires self-consciously asking, “How do we talk? Who do we cater to?”

Do emerging adults like the emergent church?

The bottom-line answer is yes. Emergent churches are on to something that seems to connect better with this wave of young people. On the other hand, demographically in the U.S., the emergent movement is a miniscule reality. Of all the emerging adults we interviewed, I don’t know that any of them were tied to the emergent church. But the movement, if it is a movement, definitely is a somewhat successful response to what’s going on in emerging adult culture. Where it exists, your average emerging adult would find it more intriguing and more engaging than a traditional approach.

But I would caution that emerging adults are smart about when they are being marketed to. So if the emergent church doesn’t offer something genuinely different from what emerging adults have too much of already, they’re not going to give it two seconds of attention.

For your next project, you plan to follow the people who appear in Soul Searching and Souls in Transition into their late 20s and early 30s. What do you expect to find?

The study has surprised me in so many ways that I’m hesitant to predict. But at the most basic level, we expect to find more emerging adults settling down, starting up middle-class lifestyles, and getting married. We know that getting married and having children increase the probability of attending religious services. So all of these life-course factors will start to bring people back to the church.

The big question is, What will the character of their faith and spiritual lives be? Will it still reflect a moralistic, therapeutic, consumerist outlook? Or will this different life phase actually change the way they engage their faith? Then there are all the interesting trajectory questions. Will early life factors help to explain or correlate with the different faith trajectories people are on? We have their early trajectories now, but it could be that when we get a fourth data point in their late 20s, we will learn much, much more. I hope so.

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Souls in Transition is available at Amazon.com and other book retailers.

Articles by or about Christian Smith in Christianity Today and Books & Culture include:

Getting a Life | The challenge of emerging adulthood. (Christian Smith, November 1, 2007)

Christian Smith on Why Christianity ‘Works’ | Plus: Baylor publishing woes, and other news from the higher education world. (September 13, 2007)

Evangelicals Behaving Badly with Statistics | Mistakes were made. (Christian Smith, January 1, 2007)

What American Teenagers Believe | A conversation with Christian Smith (January 1, 2005)