Touchstone Pictures

Touchstone PicturesBridge of Spies is based on the true story of James B. Donovan, who acted as the Official Unofficial U.S. Representative during Cold War negotiations between the U.S., East Germany, and the U.S.S.R. Donovan, if the movie is anything close to accurate, was the kind of man Tom Hanks was born to play: smart and determined, but most of all humble.

Donovan starts out as the pro-bono lawyer of Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance)—a man accused of being a Soviet spy. His law firm clearly expects Donovan to merely offer a perfunctory defense; privately, the judge asks him, "We all know he's guilty—why put up a fight?" But Donovan is convinced that the appearance of a working system needs to be matched with the actuality of a working system—and not only pursues an appeal for Abel on constitutional grounds, but convinces the judge to not condemn Abel to death.

There are moments throughout the film, like the one where Donovan argues against the death penalty for Abel, where the brilliance of Hanks's casting becomes clear. Donovan, all allegiances aside, thinks that Abel is simply following his government's orders, which Donovan considers to be an honorable action, no matter whose side you're on.

At the same time, Donovan knows that having a Soviet spy ripe for the trading would be a primo diplomatic advantage for the US. Hanks's genius is in taking two motivations—one pragmatic, and the other idealistic—and intertwining them with such sincerity that you really believe both halves. (That this is a result of our most American actor being directed by our most American director, the latter-day equivalent of Frank Capra and Jimmy Stewart, is probably pretty telling.)

And when a top-secret U.S. spy plane is shot down over Soviet territory, leading to the capture of test pilot Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell), Donovan's gamble pays off. He's sent to East Germany to negotiate the release of Powers in exchange for Abel—though, idealist through and through, Donovan also attempts to lump the release of an American student caught on the wrong side of the Berlin Wall.

Touchstone Pictures

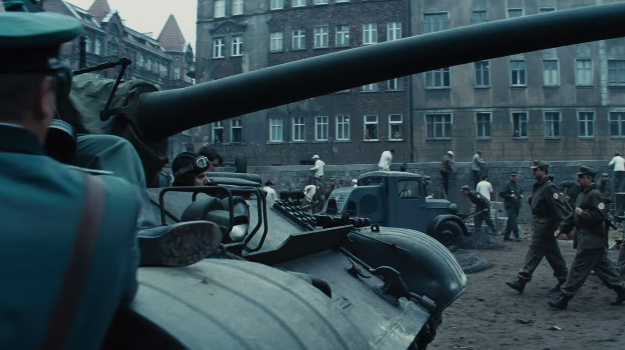

Touchstone PicturesThe result is one man, acting in no official capacity for the U.S. government, negotiating with two nations (one a subsidiary of the other) and with people who have no official ties to the government they "represent." The stakes ratchet up, but Spielberg keeps the tension at a low simmer. Donovan is less James Bond, and more Jimmy Stewart going to East Germany brandishing ideals and smarts in equal measure.

Spielberg's direction is so deft and seemingly effortless that it's easy to take for granted how well-composed everything is. Remarkably, the first twenty minutes of the film lack music, allowing you to read the scene for yourself to determine its feel, rather than having it blared at you. Even when it appears, the music is subtle and appropriate throughout. The costuming is wonderful, feeling authentic instead of caricatured, and the shift in color palettes between the U.S., West Berlin, and East Berlin does more for generating a mood than any speech or soundtrack could.

That everything is so technically high-quality across the board makes it pretty difficult to figure out whether Bridge of Spies is actually a good movie. It's certainly an extremely Spielbergian movie: the negotiation of Lincoln plus the espionage of Munich plus the moralizing monologues of Amistad.

This isn't to say that Bridge of Spies is the sum of those parts–simply that everything in the movie is extremely familiar. On one level, appreciating the film means appreciating the way Spielberg can reduce a story to its purest, most Platonic components. There's absolutely nothing in the film that doesn't need to be there.

Touchstone Pictures

Touchstone PicturesBut this also deprives the movie of an edge, or spark of life, or whatever you want to call it: the film plays like a succession of very well-crafted, technically superb Moments, but its grounding isn't inside the movie. Moments are imbued with gravitas not because they're powerful, but because you know Spielberg did them. And the fact that Tom Hanks is so clearly our nation's Everyman also means that his character doesn't get little humanizing moments—after all, why waste time fleshing out your lead when Tom Hanks's name alone means you don't have to?

The arc of Bridge of Spies is that Donovan is right, and people don't realize it until after the fact; this is the first act. Then, in the second act, Donovan is right, and people don't realize it until after the fact. Roll credits. Rather than characterizing the difficulty Donovan had in accomplishing his task (aside from a few cases of mistaken identity), the film makes him so resolute, and determined, and relentlessly right (both in the moment and morally), that we lose the ability to relate with him.

Compare Spielberg's treatment of Donovan with Aaron Sorkin's Steve Jobs: the latter figure is immanently relatable, but not because everyone in the audience is a genius aesthete designer. It's because we're all flawed. Sure, we probably rarely deny the paternity of our own children—but something in the combination of insecurity and determination in Jobs makes him not only fascinating, but relatable.

Touchstone Pictures

Touchstone PicturesBridge of Spies offers only the determination–only the high notes, as it were, with none of the lows. And in eliminating the lows, Spielberg mutes our experience of the highs. Bridge of Spies is an amazing technical achievement, and is sure to please any fan of Spielberg, but it lacks the personal spark that makes Spielberg at his best so captivating.

Caveat Spectator

We see some East Germans attempt to climb the Berlin Wall and get leveled in a hail of gunfire—there may have been a bloody streak or two, but it is not very graphic. Some minor profanity is briefly used.

Jackson Cuidon is a writer who lives in New York City with his wife and dog. He Tweets once in a while @jxscott.