"Le vent se lève! . . . Il faut tenter de vivre!" ("The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!")

This quote from Paul Valéry's poem "Le Cimetière marin" opens and is repeated throughout Hayao Miyazaki's The Wind Rises, a gorgeous and existentially contemplative film recently nominated for the best animated film Oscar (it lost to Frozen).

Miyazaki—a legendary Japanese filmmaker/animator (Spirited Away, Howl's Moving Castle)—is in the twilight of his career, and The Wind Rises is an appropriately epic, stately, and somber capstone to his six decades of acclaimed work. Its pace is more Ozu than Lego Movie, and its subject matter (building Japanese war planes in the years leading up to World War II) is hardly typical of the animated genre, but The Wind Rises is a masterful film. It deserves a wide audience.

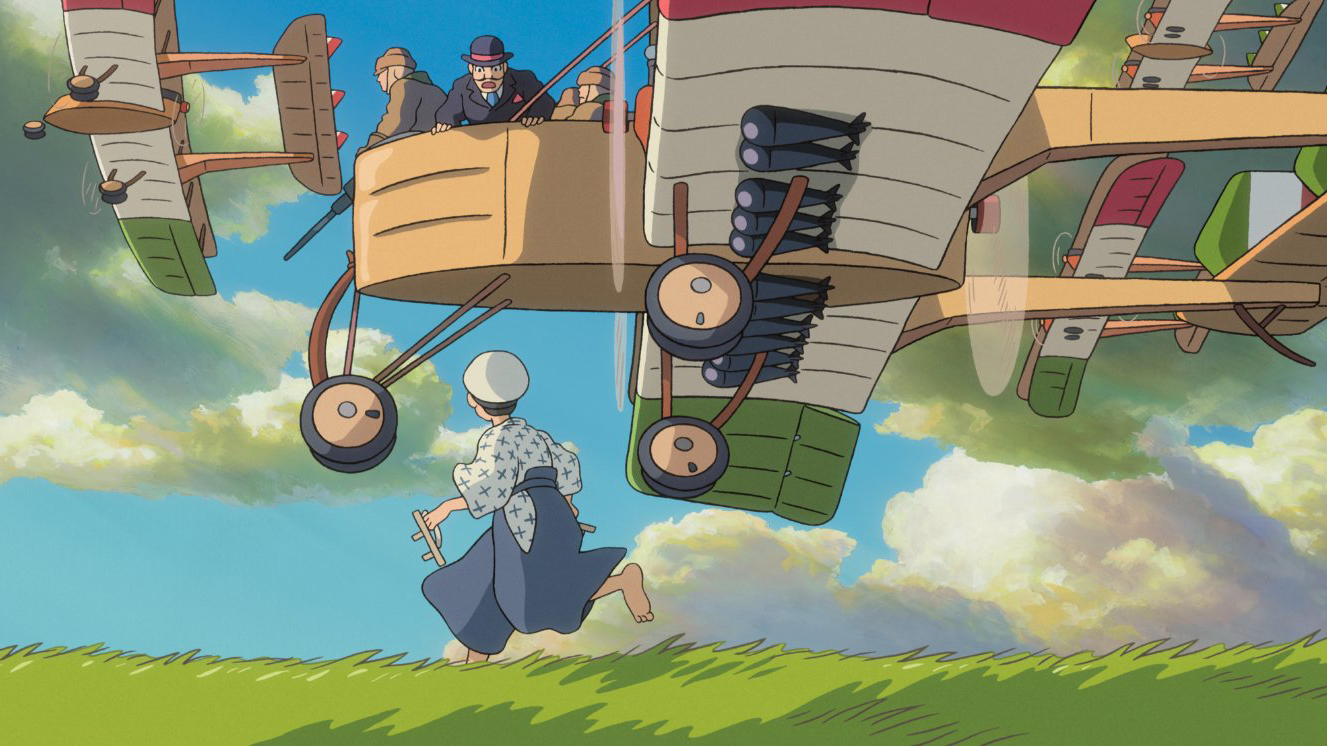

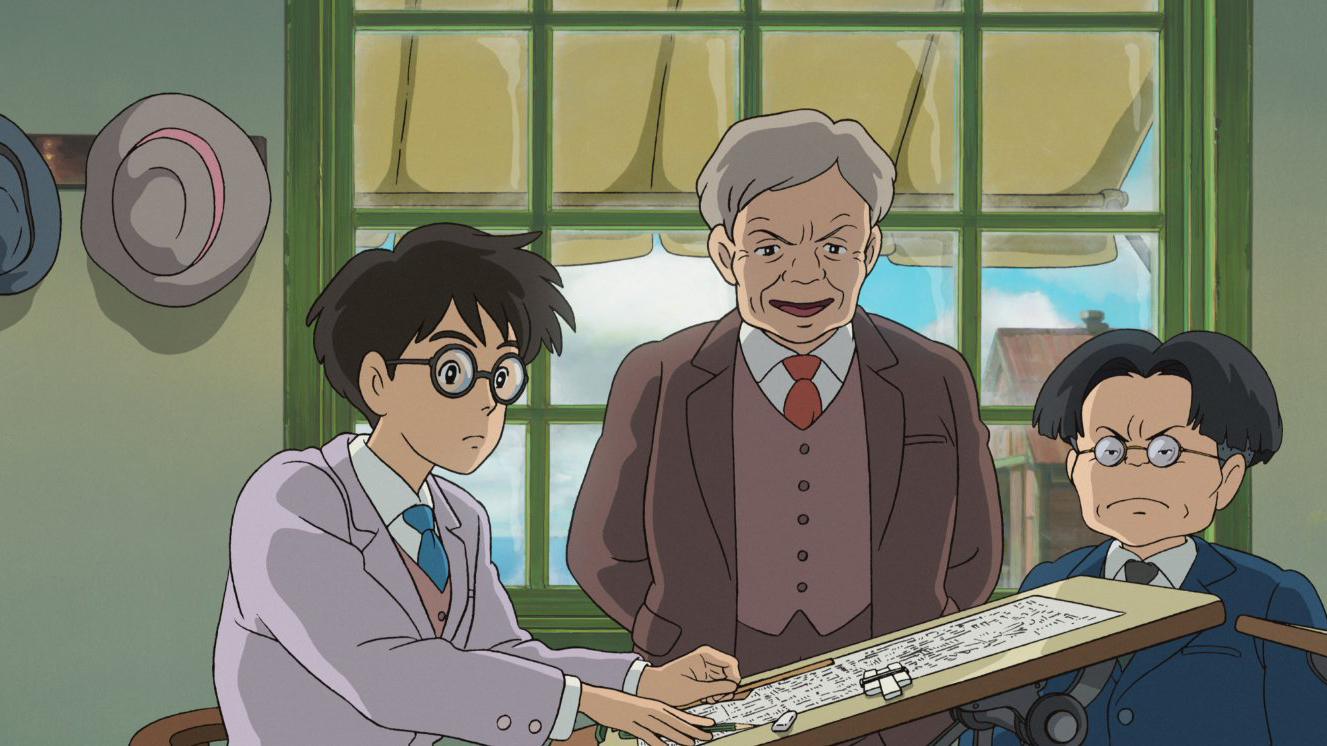

The anime film is a fictionalized biography of aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi, who helped design and develop the planes that would be used by Japan in World War II. We see Jiro as a boy who dreams of flying planes but, due to poor eyesight, settles on the dream of building planes. He goes to college for it and quickly becomes the engineering prodigy of his country's developing aviation industry.

Jiro (voiced in the English-dubbed version by Joseph Gordon-Levitt) may be a nerdy engineer, but Miyazaki portrays him as an artist. His canvas is the sky and his paintbrush is the slide rule. The film's tension comes from an artist trying to do what he loves within the constraints of industry and practical life—in this case, a growing military industrial complex forking over huge amounts of money for planes designed to be agile killing machines. Jiro would rather his planes be elegant and graceful, without guns or bomb-dropping mechanisms.

But as it is, he is alive and in the prime of his engineering life at precisely the moment when the world is readying itself for war. As one character notes, any artist—including a plane engineer—has about ten years during which he or she is at the top of their craft, making their best work.

The winds of Jiro's life blew him into this place and time and for this task: to make the most well-designed war planes possible.

Miyazaki, an outspoken pacifist, doesn't critique Jiro for his role in perfecting the machinery of death in advance of World War II. Rather, he laments the way that such talent is twisted and such artistry leveraged for the ugly machinations of nations at war.

Set against the ominous backdrop of modernity's march to replace the pastoral with the industrial (an image of oxen carting war planes to a grassy runway epitomizes this), The Wind Rises is above all an elegy for the impermanence of beauty, art, love, and ultimately life itself.

The animation itself reflects this: painterly, almost Monet-esque landscapes populate the film, as well as whimsical visions of cloud, flight, and fancy. Yet this is juxtaposed with imagery of fire, destruction (the 1923 Kantō earthquake and fire) and war. There's skepticism about modernity and a romantic fondness for nature and the pastoral here, in a manner not unlike Terrence Malick or Werner Herzog (who lends his distinct voice to a German character in the film).

But The Wind Rises is not just a critique of technology. It actually has some admiration for technology as a new playground for innovators and artists.

No, the film is more elemental in its lament: whether by technology, or war, or tuberculosis, or a downpour that ruins the canvas of a painting-in-progress, all things will come to an end. The Wind Rises is a poignant example of the sort of wise, quiet sadness that imbues much of the best Japanese art with a "sun-setting" sense of the temporal.

This being a Japanese film, the emotion of Rises is not of the tear-jerking variety (see Up and Wall-E) but is more subtly woven into the brushstrokes of the narrative. Still, it's hard not to leave this film feeling an existential weight somewhere between sehnsucht and sunt lacrimae rerum: a bittersweet longing for a world without sickness and death; a world where the cheery dreams of childhood can live into the future without being bungled by bureaucracy or tainted by the harshness of practicality; a world where a love story like that of Jiro and Naoko (voiced by Emily Blunt) doesn't have to end in tragedy.

Jiro dreams of making beautiful airplanes (his dream life is an active, cathartic presence throughout the film), but even his chosen medium is not without its inherent nightmares. As one character points out to Jiro: "Airplanes are beautiful, cursed dreams waiting for the sky to swallow them up." Cursed dreams. This is the thematic heart of the film.

But in spite of all of this, the urge to create persists. As an artist himself, Miyazaki doubtless is all too familiar with the myriad of reasons to despair, give up, or give in to the man—yet at 73, he still finds inspiration to keep making art the way he wants to.

The wind will always rise, taking us up to new heights, blowing us where we least expect and sometimes blowing us back to the ground. There's something "Forrest Gump fatalistic" about this, perhaps. Or maybe it's a more divinely orchestrated wind, bringing winds of both blessing and misfortune. Either way, suggests Miyazaki via Valéry, our response should be the same: come what may, "We must try to live!"

Caveat Spectator

The Wind Rises received an odd rating for an animated film—PG-13, mostly for frequent images of characters smoking. There are also some violent images (destruction from earthquakes and fires, planes crashing, one character coughs up blood) and a few mild curse words. Themes of war and death also lend the film a sometimes ominous tone.

Brett McCracken is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist, and author of the books Hipster Christianity: When Church and Cool Collide (Baker, 2010) and Gray Matters: Navigating the Space Between Legalism and Liberty(Baker, 2013). You can follow him @brettmccracken.