We Americans have fashioned many Dietrich Bonhoeffers for ourselves in the decades since the German theologian was put to death at the Flossenbürg concentration camp in 1945. In The Battle for Bonhoeffer: Debating Discipleship in the Age of Trump, Rhodes College professor Stephen R. Haynes offers a survey of the varied interpretations of that remarkable man, excavating the ways his name and legacy have been used—and too often misused—in American public discourse. Haynes holds up a mirror and asks, “Who do we need Bonhoeffer to be? And how is this need affected by the way ‘we’ define ourselves and the threats we face?” In other words, the battle is not really for Bonhoeffer, and the image in the mirror is our own.

Of course, with words like “battle” and “age of Trump” right there on the cover, this book crosses territory rich in minefields. Like an embedded journalist feverishly filing stories from the front, Haynes writes knowing that he cannot fully account for all the Bonhoeffer-ing happening around him, especially in our undulating political times. But because Bonhoeffer is employed for all kinds of ends in American political discourse, and his legacy used to burnish others’ public profiles, Haynes balances a commitment to the protocols of the academy with a burden of responsibility to speak directly to our current political moment.

History and Hagiography

In the first part of the book, Haynes recounts the history of Bonhoeffer’s reception by the American public through sketches he amassed in his 2004 volume The Bonhoeffer Phenomenon. He revisits and updates those earlier types, including the liberal, the radical, the evangelical, and the universal Bonhoeffer. To these Haynes adds a new sketch—the “populist Bonhoeffer.” (More on this later.) Most illuminating for me was Haynes’s discussion about Jewish evaluations of Bonhoeffer’s legacy, especially that he has been reviewed by Yad Vashem (Israel’s Holocaust memorial) and refused recognition as a “righteous Gentile,” a term reserved for those who took extraordinary personal risk to save Jews.

Haynes devotes a full chapter to the history of how American evangelicals have received Bonhoeffer. While they tend to be familiar with the pastor’s devotional writings (likeThe Cost of Discipleship or Life Together), Bonhoeffer’s university lectures, sermons, and his later prison letters (where, for instance, he mulls over his idea of “religionless Christianity”) presented real obstacles for evangelicals in the late 20th century. These theological concerns faded, however, as his life story became more widely known, feeding a steadily growing focus on his resistance work against the Nazis. Evangelicals creatively engaged his story in documentary films, an award-winning radio drama, and even a Christian romance novel in which, writes Haynes, “Bonhoeffer serves as the main character’s spiritual inspiration.”

Having sought himself to make Bonhoeffer’s life and thought accessible to general readers—with Lori Brandt Hale, he co-authored the Bonhoeffer edition of the Armchair Theologian series—Haynes acknowledges value in some of the quirky ways Bonhoeffer's life has been interpreted for American evangelical audiences. Although he prefers history to hagiography, naming certain popular treatments with that derisive term, his posture is not one of an arrogant academic trying to raise the guild's drawbridge from storming peasants.

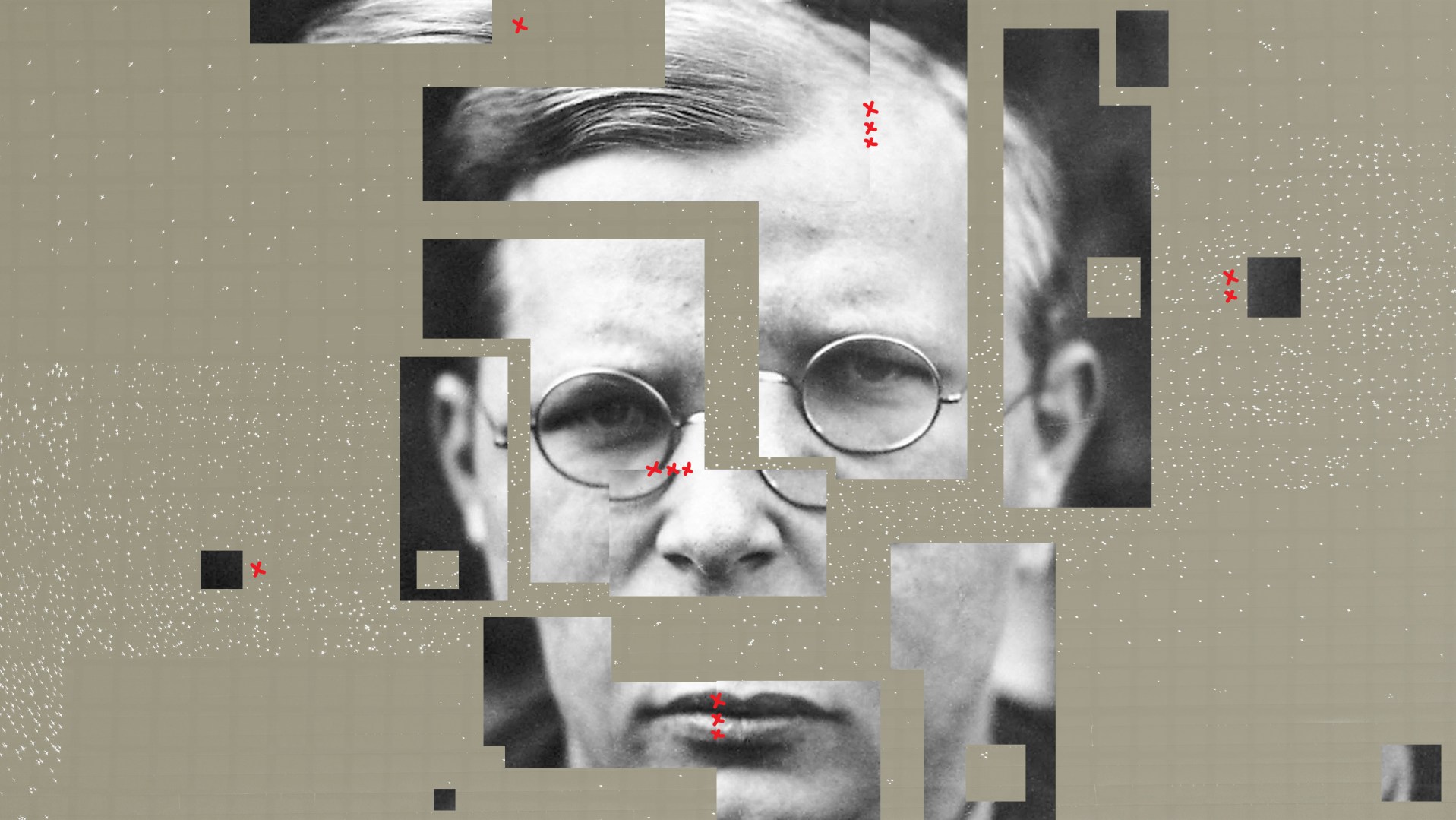

Bonhoeffer’s name gained an even wider dissemination in American political discourse, Haynes notes, following the terror attacks of 9/11 and the growth of the internet as a means of communication. Politicians, public theologians, and other cultural leaders drew on Bonhoeffer with greater frequency, and urgency, in the post-9/11 national debate. Bonhoeffer was invoked both in support of and in opposition to the 2003 war with Iraq. Critics of the war referred to him again as the war continued far longer than the Bush administration anticipated. Online media elevated Bonhoeffer to a wider range of Americans. (And now, in the age of social media, misattributed quotes are often superimposed on photographs of his face, which are then traded as virtue-signaling currency.) For wherever Bonhoeffer stands as an imagined brother-in-arms for one’s side, the other side is, well, Hitler.

That form of inflammatory rhetoric was fanned hotter during the Obama administration, when conservative Christians, feeling politically and culturally embattled, drew heavily on Nazi-era terms as a means of making sense of the moment and calling the faithful to urgent political battles. For example, the public’s and courts’ changing views on homosexuality and marriage law represented “Gestapo-like” threats to religious liberty. Amidst this maelstrom, Eric Metaxas first stepped onto the Bonhoeffer interpretation stage in conjunction with the 2009 Manhattan Declaration, a joint statement from Orthodox, Catholic, and evangelical Christians on abortion, marriage, and religious liberty. Metaxas compared it to the Barmen Declaration, issued in 1934 to denounce German churches that had meekly submitted to Nazi ideology.

Shortly thereafter came a watershed event, the 2010 publication of Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy. At this juncture, Haynes’s narrative takes a decidedly more personal and pointed tone. Haynes writes that Metaxas’ wildly popular, engaging biography of Bonhoeffer grabbed the academic Bonhoeffer guild by the collar. The deluge of interest was unprecedented, and the guild was forced to take notice. And respond they did, with force, warning in many reviews that the Bonhoeffer depicted by Metaxas was molded and marketed for conservative American evangelicals. Metaxas seemed to have fashioned a Bonhoeffer that would inspire them, fight with them in the culture-war trenches, and stand shoulder-to-shoulder against an overweening federal government. Enter the American-populist Bonhoeffer.

The Metaxas book does present interpretive problems, but it is Metaxas the man that Haynes brings under special scrutiny. He rebukes Metaxas’ casual use of Bonhoeffer in his own political commentary, speaking to him directly in a short paragraph close to the end of the book. Metaxas has made clear that he wants to liberate Bonhoeffer from the clutches of people like Haynes and Charles Marsh (who writes the thoughtful, self-examining foreword to the book), casting aspersions on their scholarship—and on them personally—for purportedly making a golden-calf Bonhoeffer, reflective of the changing times.

But just as Metaxas wants to rescue Bonhoeffer from the liberals in the academy, Haynes makes clear that he wants to liberate those evangelicals he sees as captive to Donald Trump. That effort complicates his attempt to rescue Bonhoeffer from misuse. Indeed, he reveals that he long argued for an open door to Metaxas, and the possibility of conversation, within the International Bonhoeffer Society. But he now believes that studied academic detachment is irresponsible. His open letter at the back of the book to “those who love Bonhoeffer but (still) support Trump” will likely fail to convince any true (political) believers.

The Bonhoeffer We Never Knew

One element I longed to read in this book was Haynes making a negative confession, a clear statement about what history cannot, indeed must not, do for us today. Why do we so often turn to the Nazi era as a way of making sense of our own? Can we really make any helpful or responsible comparisons between that history and our own day? Does this kind of thought experiment equip or hinder our imaginations as we grapple with our own contemporary responsibilities?

One might say we need to encounter the Bonhoeffer We Never Knew, a man situated within the complexities of his place, his culture, and his relationships. Haynes’s historical mirror shows that we prefer him in American cultural packaging, a hero whose tale is told with a bright spotlight and clear principles. Cast in that light, however, it becomes all too easy to draw tenuous parallels between Bonhoeffer’s life and ours, just as we do with heroic figures from Scripture. We all identify with David, for instance, and never Goliath. So too are we all Bonhoeffers, but never the complicit “German Christians” who go along to get along, hum the nationalistic hymn, or refuse to care about the downstairs Jewish neighbors who haven’t been seen for some time.

Can Bonhoeffer set the political or cultural captives free? In the end, he cannot. This task is not what his life is for. This is not why we tell Bonhoeffer's story and tend his memory. Invoking his name confers no special righteousness upon us or our causes. Haynes has done a valiant job taking stock of the varied elements of our American idea of Bonhoeffer, but sadly, we can only see ourselves in such pixelated, polarized images. If anything, learning more about Bonhoeffer’s life and times should motivate us to live more prudently, courageously, and responsibly within our own. That is Haynes’s stated hope—but it is also Metaxas’s. So the battle continues.

Laura M. Fabrycky is an American writer living in Berlin, where she serves as a volunteer guide at the Bonhoeffer-Haus. (The views she expresses here are her own and do not necessarily represent those of the Bonhoeffer-Haus.)