A cursory search of academic dissertations reveals a new interest in the origins of insults and curse words. For instance, I learned recently that the insult “phony”—as in “She acted like she was into EDM [electronic dance music], but then we found out she was a phony”—entered our lexicon with the arrival of the telephone. People started phoning other people randomly, pretending to be someone they weren’t. These were the original “phonies.”

The Happiness Effect: How Social Media is Driving a Generation to Appear Perfect at Any Cost

OUP USA

368 pages

$16.21

New technologies always give rise to new cultural anxieties. As John M. Culkin said in summary of Marshall McLuhan’s work, “We shape our tools and, thereafter, our tools shape us.” If the modern news media had existed in the early 20th century, TV anchors would have breathlessly warned parents about the threat of phonies coming after their children. Websites would have compiled listicles with “eight signs your son is a phony.” And journalists would have dialed up leading psychologists to ask for tips on talking to college students about phony-ism.

Nowadays, it’s social media that has us worried, as stories of cyberbullying and “sexting” surface with alarming frequency. Parents, educators, church leaders, and even young people themselves want to know what Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—not to mention the smartphones that make them omnipresent—are doing to us. We all have feelings and theories on the ill effects of social media, but these are only anecdotal. Surprisingly little direct study has been attempted.

Onto this turf steps sociologist Donna Freitas with her book The Happiness Effect: How Social Media Is Driving a Generation to Appear Perfect at Any Cost (Oxford University Press). Freitas, also the author ofSex and the Soul, comes from an epicenter of sociological research on adolescents and young adults, Notre Dame’s Center for the Study of Religion and Society. She gathered her data in part from online surveys, but mostly from 200 interviews with students at 13 universities. What she discovered was people in desperate need of hearing some crucial gospel themes.

Loss of Vulnerability

The Happiness Effect is organized around the topics covered in these conversations. Each chapter overflows with personal stories, making the book an enjoyable read. But on a deeper level, Freitas has a theory to test. She contends that headline-grabbing abuses like bullying, stalking, and sexting are not the greatest dangers that social media poses for young adults. Rather, they distract from a more insidious phenomenon: the drive to look perfectly happy, all the time.

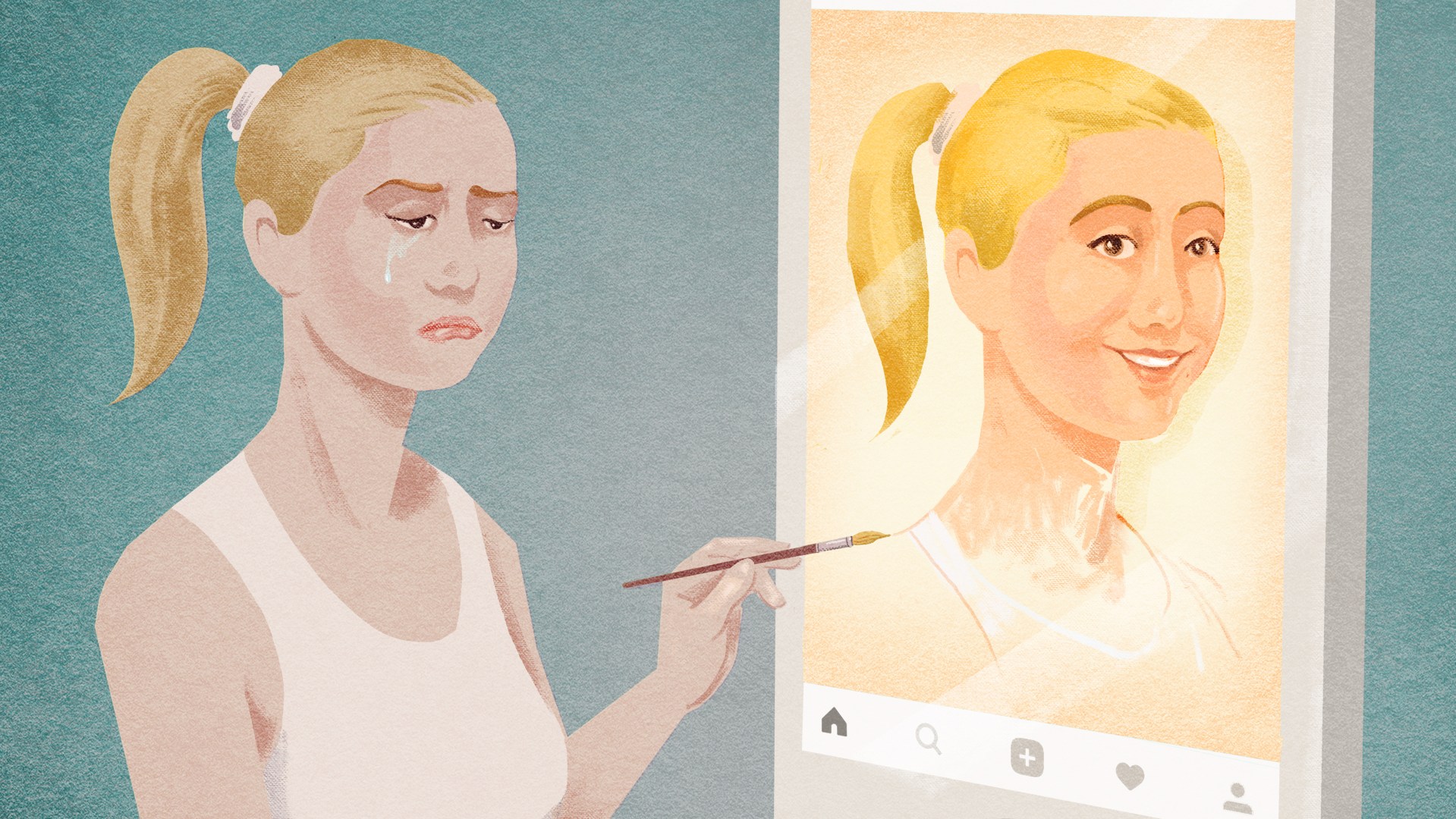

In her interviews, Freitas found that college students have an overwhelming urge to present themselves as successful and happy. Many reported that it was nearly unthinkable to present themselves in any other fashion. They were all shockingly aware of the watchful eyes of their peers—and of the corresponding need to routinely spiff up their profiles. Freitas’s concern is that young adults too rarely experience anything like genuine vulnerability. Like anyone else, they endure stretches of suffering, fear, and failure, but they’re afraid of discussing them candidly.

The result is a great many young people more concerned with appearing happy than with really being happy. She begins by showing how this mentality encourages nonstop peer-to-peer comparison. Many young adults, says Freitas, constantly use social media to compare themselves to others. While envy and insecurity are nothing new in high-school or college environments, social media greatly amplifies their reach. No longer is comparison limited to quads, hallways, or football games. Instead, it becomes a 24/7 sport, with pictures, profiles, and status updates displaying legions of happy people having amazing experiences alongside beautiful girlfriends and handsome boyfriends. Freitas discovered that “FOMO” (the fear of missing out) is an actual burden young adults face. But they suffer in isolation, because to post sadness, depression, or fear would only reveal that they are not happy, and therefore losing at the game of life.

Reading this, I couldn’t help thinking of Søren Kierkegaard’s haunting insights in Works of Love. Kierkegaard reminds us that love is flattened (and maybe obliterated) when comparison enters our relationships. If social media turns us all into micro-celebrities, as Freitas seems to suggest, then we must ask if the human spirit is wired to thrive (or crumble) under the constant evaluation of strangers.

Freitas then shows how most young adults are deeply aware of managing a personal “brand.” Her interview subjects even called this “manicuring their presence” and recognized that they often curate images to present the intended picture of happiness. Freitas says this temptation to self-brand is not necessarily due to consumer culture or reality TV, but to adults and institutions on the horizon, like universities and companies. Stories of how employers and admission counselors scour social media posts have convinced them that Facebook should be only a highlight reel of success and happiness. Many even do “Facebook clean ups,” deleting posts from junior high and high school that don’t fit their current brand.

The Happiness Effect then moves into more specific topics like selfies, religion, bullying, dating, and sexting. These chapters offer plenty of surprises. First, Freitas reveals that young adults are well aware of their practices—they understand, for instance, how selfies can nurture self-centeredness. They are making moral judgments, or at least thinking about the “goods” of social media. But they’re not nearly as worried about the hazards of sexting and cyberbullying as their parents. Freitas shows that while some young adults are bullied, engage in sexting, and use apps to hook up (sexually) with strangers, these experiences are actually rare. For instance, only 3 or 4 of her 200 interviewees had experienced cyberbullying, and none had used social media to facilitate sex with (or even start dating) a stranger.

In her chapter on religion, Freitas shows how young adults from different faith traditions navigate the world of social media. Evangelical young people, she reports, use these platforms for witnessing, often appearing happy as a testimony to Jesus’ work in their lives. Muslim women, meanwhile, look to subvert restrictions on their religious practice, while Orthodox Jews find a window into a secular world their tradition often keeps hidden.

The book concludes with an odd mix of the hopeful (young adults are often aware of the dangers of social media) and the pessimistic (even so, they still succumb to its temptations). Freitas discusses how, for large numbers of young people, the cell phone is a trap. They aren’t sure they could live without it, but they yearn nonetheless for a time when it didn’t exist. She sees a kind of Stockholm syndrome at work—the devices torture them, but somehow this only enhances their appeal. Something similar happens with young adults who have tried quitting social media. It appears that, like kicking a smoking addiction, it’s awfully tough to keep old desires and habits at bay.

The Perfection of Jesus

For those seeking to support and minister to young adults, The Happiness Effect is a must read, but not for the reasons you might assume. Parents, pastors, and youth workers may feel relieved to find evidence that social media isn’t quite the moral wasteland of risky behavior they’ve been led to believe, especially with regard to bullying and sexting. But this relief will soon be met with a deeper unease. Social media becomes a mask that hides the depth of young adults’ need for Jesus.

In Scripture, we see Paul discussing the Christian faith as the experience of the living Jesus. Yet Paul would have found it difficult to describe this experience in today’s social media climate, since Jesus worked through him most clearly in experiences of weakness and suffering, the very experiences young adults seek to delete or gloss over.

Paul knew that Christian faith involves the very public articulation of suffering and weakness, seeking for the living Christ to minister to us in and through them. The churches he helped build were grounded not around achievement, but in the willingness to suffer with and for each other. This, then, is the great danger of social media: With its assumptions of perfection, it keeps young adults from courageously opening up the depths of their experience to seek God’s action in and through their moments of loss, rejection, and fear. The centrality of confession, forgiveness, and transformation in Christian faith means that perfection is never something any human being can achieve. We are always in need of the perfection of Jesus, which we find not in polishing up our lives and manicuring our profiles, but in confessing our weakness and need for others, and especially in the finished work of Christ on the cross.

As Freitas puts it, Facebook and Twitter are, in a way, the anti-confession, the places we pretend that we have it all together, as though we were the gods of our own future. The gospel challenges the assumption that confessing weakness and need makes you a failure. Those who minister to young adults will have an important task in opening up space for them to honestly confide their brokenness. It is only here that transformation happens, as God meets us in our weakness.

Andrew Root teaches youth and family ministry at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is the author of Bonhoeffer as Youth Worker: A Theological Vision for Discipleship and Life Together (Baker Academic).