The most tasteful invitation to contemplative prayer I have ever experienced was in a garden next to a charming British mansion. Along a path meandering through flowers and shrubs a series of interactive spaces featuring signs with relevant Scripture passages and instructive prayer prompts—specifically designed to help the visitor process grief after loss.

In this garden, I am encouraged to sit on a bench and imagine a lost loved one in the empty seat next to me. I can sit in a rowboat near a stream and recall the stormy waters I have endured in life. I can pick up a stick from a pile, identify a concern or wound, and release it to God by tossing the stick into the stream. I can even download an app to play meditative music along my journey.

My wife, Cheri, and I visited this Remembering Garden at Waverley Abbey in Surry, England, founded by the Order of the Mustard Seed (OMS) community as part of their 24-7 Prayer initiative. We went there after attending and speaking at the New Monastic Roundtable in Switzerland in 2023, which is a global network of 20 different intentional Christian communities like OMS who are seeking to adapt ancient monastic principles and practices to enrich modern faith and life, including designing sacred public spaces for contemplative prayer.

I returned home filled with renewed appreciation for these and other fresh expressions of the ongoing new monastic movement. This movement was first introduced 20 years ago by the dreadlocked Shane Claiborne on the cover of Christianity Today. So I was more than surprised when, a few months ago, I heard a leader who runs in some of the same circles say casually, “The new monasticism is dead.”

While it’s true that traditional monasticism is declining in many historic Christian traditions, new monasticism—the contemporary reappropriation of monastic wisdom—is still very much alive. More than that, the movement is gaining a new and growing following among the next generation and is meeting universal human needs that are felt more now than ever.

In our global digital age, many Christians are rediscovering the importance of community, the value of rhythms and routines amid chaotic circumstances, and the need for deeper commitment to spiritual formation. Over the past five years alone, the pandemic, incidents of racial injustice, and the church abuse crisis have led to a wake-up call. We are realizing that it may be worth sacrificing modern comforts and conveniences to live out our highest ideals and potential as God’s people and that we may need to look back in order to go forward.

Some believers have been sensitive to these needs for a long time—people who consider themselves “new monastics” (like me), who are fascinated by the desert elders’ courage to relocate to abandoned places. We are intrigued by the idea of living in a close community and making serious commitments to fundamental values. We wonder if establishing communal rules for life might tame the wild horse of late modern culture and help us better order our lives around the gospel.

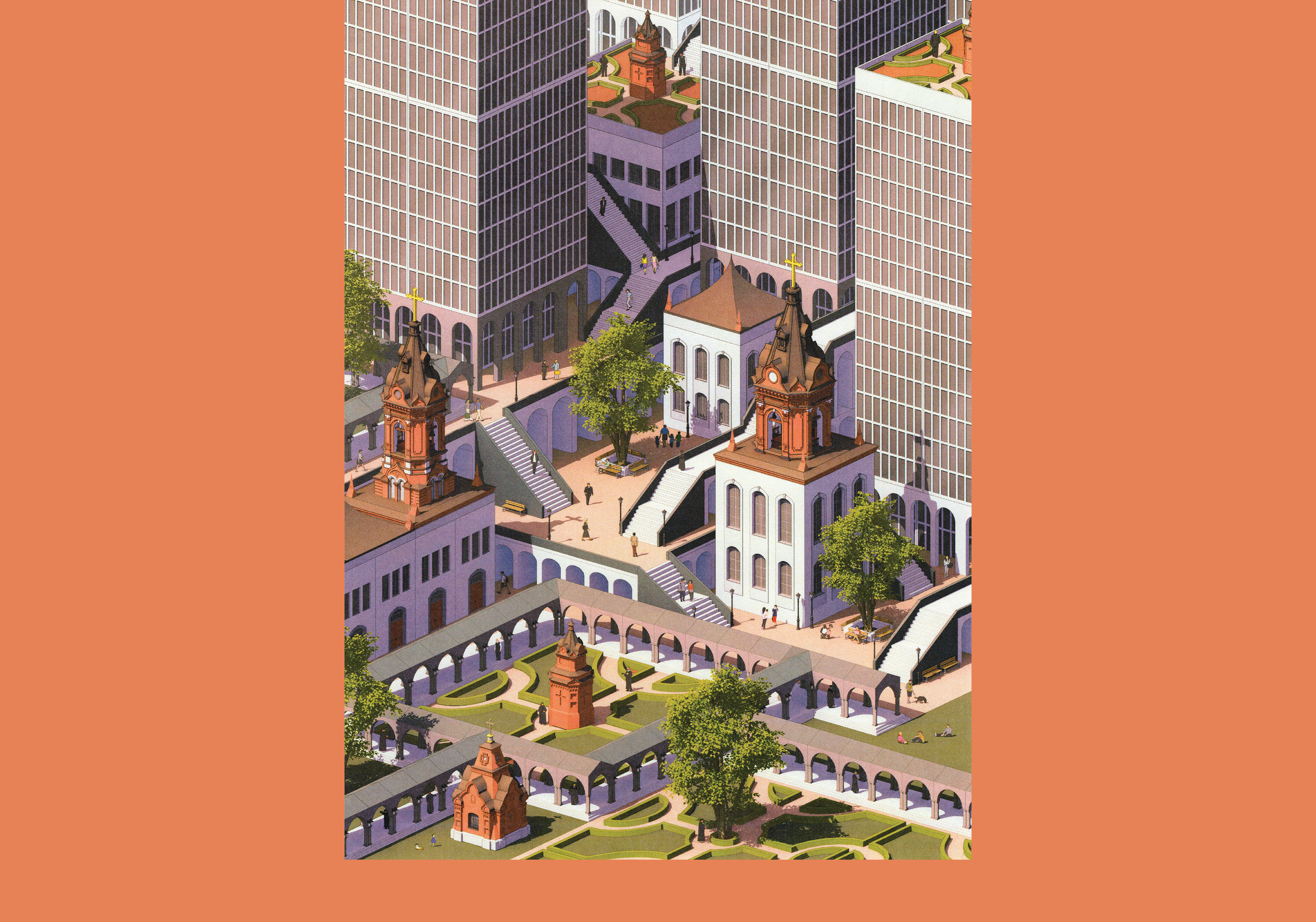

Today, this reappropriation is taking the form of devotional apps like Lectio 365, introductory virtual classes on contemplative prayer, repurposed convents in Europe, and prayer spaces in alleyways and financial districts. It looks like Christian university campus houses establishing their own rules of life or communal discipleship programs, and small “colleges” of Christian students attending larger universities. It is happening through globally dispersed organizations like OMS, which takes prospective members through stages of preparation and vow-taking in a digital initiation process modeled after traditional religious orders.

It’s worth noting that the term monasticism is more complex than our present usage suggests. For centuries, religious lawyers have debated distinctions between monks and friars, simple and solemn vows, religious and consecrated life, and so forth.

Once, when I was presenting a session for the American Academy of Religion conference, one responder simply said of the new monastics, “They are not monastic. They do not make vows of chastity.” End of discussion. It would probably be more appropriate to say we subscribe to “institutes of consecrated life,” but that term is rather obscure. The reason most people still use new monasticism is because it seems fitting for a movement eager to retrieve the practices and sentiments of a radically religious form of life.

Christians who are interested in monastic principles want to take up a distinct lifestyle that will help them mature in Christ. Some of us have found a need to fast, spend time away from social interaction, or meditate on our own sins before God. Like those who compete in the Olympic Games, or consecrated virgins, members of monastic orders go “into strict training”—not to run “aimlessly” but, as the apostle Paul writes, to “strike a blow to my body and make it my slave so that … I myself will not be disqualified for the prize” (1 Cor. 9:24–27).

The technical word for this kind of activity is asceticism, but most talk about it in terms of formation. Author Trevin Wax wrote last year that spiritual formation—defined as “a total reworking of personal habits and spiritual disciplines” out of “allegiance to Jesus as Lord of all life”—is the fourth and most recent wave of influence shaping evangelical churches today.

Wax is on to something, as many of these next-generation expressions of new monasticism are keenly focused on spiritual formation.

For example, John Mark Comer, the author of the recently popular book Practicing the Way: Be with Jesus. Become like him. Do as he did., has noted a “micro-resurgence” in the common monastic practice of adopting a rule of life as a way to live more intentionally and meaningfully.

Most religious orders are governed by rules of life, which define daily rhythms and devotional routines for the community and its individual members. Such statements usually consist of a clear vision, habits for prayerful self-reflection, and practical ways to maintain accountable relationships and care for one another.

The idea behind this is that we are all being shaped by a rule of life whether we realize it or not. So we can either conform to the social rules our culture sets for us or we can adopt an intentional vision that casts Christ’s lordship over every area of our lives, even in their most mundane aspects.

Such a goal can be accomplished without written rules, of course. I once visited one of the oldest monastic expressions in Christian history: the monastery of St. Antony in Egypt. The order there is not governed by a written rule—they had such well-established patterns that recorded regulations were deemed unnecessary. Nevertheless, for those of us without 1,500 years of accumulated wisdom or an unspoken culture of life, writing down a clear statement of our God-inspired aims can be helpful.

Jared Patrick Boyd, founder of the Order of the Common Life (OCL)—a “missional monastic order reimagining religious vocations for the 21st century”—affirms a communal rule of life that is summarized in four rhythms (bodily labor, prayer, study, and rest) and 12 commitments, including simplicity, hospitality, and service to the church.

Yet Boyd insists these are not merely devotional practices. “You can do spiritual disciplines all day long,” he told me in our interview, “but if it is not toward this particular theological understanding of the shape of the human soul and the work of God, then it does not really fit the tradition.”

OCL currently has five vowed members, but 65 novices are in process and another 45 postulants will begin in 2025. Its goal is training Christians—largely online through virtually dispersed groups—to become “spiritual mothers and fathers” in their own ordinary community settings, forming “evangelists for the love of God” in their churches and places of work.

A notable feature of monastic life, both then and now, is that members see themselves as constituting an alternative community. Both of these words—alternative and community—are crucial for our embodiment of the ancient Christian faith in our disconnected, frenetic lives and communities.

We live in a rapidly changing world, not least because of the technology that we live by, such that both community and alternative become hard to understand, let alone embody. “As we become more affluent, individualistic—we lose our aptitude for community and we do not know how to get it back,” said David Janzen of Reba Place Fellowship, a small but long-standing intentional Christian community.

Too often, spiritual formation is discussed in terms of individual growth in Christ, when that is only a small part of the story. Jesus and the New Testament writers make it clear that the Holy Spirit was given “to us” (Acts 15:8) and that the Christian life is meant to be a communal one (Rom. 12:5). That’s why most of Paul’s letters in the New Testament were written primarily to churches—because God’s plan has always been to prepare a people, a royal priesthood, the body of Christ, reigning with God forever (1 Pet. 2:9). Whether we like it or not, all of us exist in the context of a community—that is the soil in which we are each planted and growing.

Monastic thinking has always held up community as a primary agent, means, and aim of God’s work in our lives. Call it sharing life, koinonia (in Greek), or “thick community,” God intended us all for authentic fellowship. Yet this kind of community certainly doesn’t come about by accident.

Too many admirers of new monastic living “think that it will just happen in community, and it just doesn’t. It takes a tremendous amount of intentionality,” said Boyd of OCL. He told me of a meeting with a few leaders from the Vineyard USA movement in 2012, where they discussed two simple questions: “(1) Is there room in the Vineyard for a monastic expression? (2) If there is room, what might such an expression look like?”

Twelve years later, this expression looks like a charismatic, 21st-century recovery of the monastic ascetical (formation) tradition—for which Boyd’s recent book, Finding Freedom in Constraint: Reimagining Spiritual Disciplines as a Communal Way of Life, is a manifesto. And although the aim of OCL is to train Christians to be on mission in their own communities and is not primarily to start residential communal expressions, they are currently exploring what a 21st-century urban monastery might look like.

But new monasticism is not simply an embodiment of community. It is an expression of alternative community. What does it look like to love the world without losing oneself within it? What does it look like to be distinct from the world without being escapist or leaning too far into Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option of “seced[ing] culturally from the mainstream”?

Alternative communities today, whether virtual or face-to-face, demand that we define Christian identity in ways that are either cross-cultural, multicultural, or countercultural. They also require conversations about nurturing common life and about learning the balance between caring for one’s family and one’s community. They open up discussions about how we can respect both the introverts and extroverts in our midst and force us to invest in the neglected practice of resolving interpersonal conflict.

Intentional and communal living has also been accompanied by wholesale commitments to practice virtue. Lifelong vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience are meant to combat some of the world’s age-old allures of money, sex, and power—and protect against the threats they pose to relationships within the community. And while modern monastic admirers may not carry on these vows in full, their traditions remain a vital source for inspiration and innovation.

For early Benedictines, a loving distinction from the world meant leaving their families to form semi-isolated cloisters—out of which they could offer charity to those in need. Today, that might look like sharing homes or incomes with others. For second-century virgins and 13th-century Beguines, chastity looked like renouncing the securities of earthly marriage for espousal to Christ. For “vocational singles” today, it may look like embracing celibacy out of reverence for Christ and in service to his kingdom.

We may not share all our income in a residential community, but we can choose to spend less and to share the rest in a common cash-sharing app, funneling funds to invest in local needs. We may not move into a cloister and recite the divine office seven times a day, but we might join a virtual group of partners to pray together daily and share self-examining reflections monthly.

We may not renounce our employment and income, but we could choose to work part-time and spend the rest of our time serving in our churches or the community. We may not choose absolute obedience to an abbess or abbot, but we might want to explore the problems and possibilities of church authority and structure and invest more deeply in a humble submission to Christ’s body.

The point in all of this is that we must learn to see commitment to these principles as simply taking the next appropriate step in the context of a loving, trusting relationship with God and others.

I dream of future monastics designing tools and spaces for 21st-century communities and individuals that creatively integrate Christian asceticism with new monastic impulses—all with the goal of meeting acute felt needs of our age and culture and facilitating the deep internal work necessary to increase our Christlikeness.

The classic collection of essays edited by The Rutba House, School(s) for Conversion: 12 Marks of a New Monasticism, lists creation care, peacemaking, sharing economic resources, and lament for racial division and active pursuit of just reconciliation as among the top marks of a new monastic way of life. Even though the New Testament speaks explicitly on such issues, these aspects have often been neglected in manuals of spiritual disciplines and formation programs until recently.

For some of us, this might look like healing our loneliness or rejection by family, friends, or society at large. For others, it means acknowledging before God what Howard Thurman calls the “hounds of hell”: our fear, hypocrisy, and hatred. Likewise, many of us need to examine and unpack the invisible racial, patriarchal, ecological, or classist backpacks we are carrying.

One of the first and simplest ways we can do this work is through our prayer life—one of the most familiar marks of monastics. Our prayers are the soil from which the entire flower of monastic life grows. Do we care for the earth and its future? It must be voiced in our prayers. Do we hate the divisions of our time? We lift our lament to the Lord. Do we want to forgive those who have wounded us? We start by airing our grievances to God. This is what prayer rooms and prayer walks are all about.

I also think future new monastics will be invested in deeper and more tangible expressions of worship. The words, structure, and spaces of our gatherings (whether liturgical or charismatic) all proclaim our faith. I long for new monastics to build more chapels and prayer gardens in busy downtowns, in tent cities, or in isolated rural hamlets. This is part of what it means to both demonstrate a commitment to a contemplative life and to offer hospitality to strangers.

As always, the form isn’t nearly as important as the heart behind it. One passion in my own work is to encourage future monastic efforts to lay aside any sense of elitism and offer steps that make “institutes of consecrated life” available and accessible to all—facilitating opportunities to experience “Community 101” via spiritual formation apps, creative sacred spaces, and guided contemplation.

We must remember that retrieving something from the past and bringing it into the present for the sake of a hoped-for future is not a science but an art. And as with any art, we cultivate modern forms of ancient principles by finding our way through the unknown—a process that can take generations.

Yet I am encouraged that we are well on our way. What I hear again and again in my conversations with leaders and followers alike is that there is a deep longing to live out the life and teachings of Christ more explicitly in our present generation. At its best, this desire is neither an expression of elitism nor an unrealistic expectation for the whole church but is rather a simple longing to make ourselves wholly available to God.

As I sat on the verdant lawn of Waverley Abbey during my visit to the Remembering Garden, I wondered if the Order of the Mustard Seed could truly keep their idyllic vision of a globally dispersed network alive—with a viral prayer app, 34 houses of prayer, 6 residential communities, nearly 1,000 members, and many other aspirations. What if all of it collapses under the pressures of finances, institutionalization, or even ordinary interpersonal conflict? It’s not that I had any secret suspicions about it in particular—I have just seen it happen to community initiatives like it many times before.

Then I remembered the words of Tim Otto from Church of the Sojourners in San Francisco when he spoke at the New Monastic Roundtable: “The church anywhere is always on the verge of failing.” Yet God’s movement in and through his church is always bigger than our perennial failures, and even the gates of hell cannot prevail against it.

Evan B. Howard is the founder and director of Spirituality Shoppe: A Center for the Study of Christian Spirituality. He is a retired professor from Fuller Theological Seminary; the author of Deep and Wide: Reflections on Socio-Political Engagement, Monasticism(s), and the Christian Life; and a friend of many new monastic communities.