Every few weeks, it seems, another AI achievement sets the world abuzz. It speaks! It paints! It digests a whole book and spits out a 10-

minute podcast!

This is generative AI, the large computing models that dazzle and worry us with their humanlike output. We’ve become accustomed to hearing about AI, but have we considered what it really offers us? Most simply: a promise of ease and justice.

With the proper application of AI, its enthusiasts tell us, we won’t have to work so hard. Our economy will be more equitable, our laws and their enforcement closer to impartial, the slow and faulty human element bypassed altogether. We will achieve a painless and mechanistic fairness.

Here, rather than dwell on any individual technological feat, I want to examine those two tempting offers. Long before generative AI became a reality, these temptations were offered elsewhere: by science fiction villains and by the Devil when he came to Jesus in the wilderness.

That fiction can be an illuminating warning, and Jesus’ response to temptation—and the manner of his ministry—can help us respond to AI in ways befitting our vocation as creatures made in the image of God.

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen may be the most prominent advocate for AI’s disruptive potential. In 2023, he published a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” beginning with an epigraph from Catholic novelist Walker Percy: “You live in a deranged age—more deranged than usual, because despite great scientific and technological advances, man has not the faintest idea of who he is or what he is doing.”

Andreessen is right that questions about human nature and purpose are central here. Yet his manifesto quickly made clear how much he differs from Percy’s Christian anthropology.

“I am here to bring the good news,” Andreessen wrote in downright messianic terms, announcing “that there is no material problem—whether created by nature or by technology—that cannot be solved with more technology.” With enough tech, he insisted, we’ll make “everyone rich, everything cheap, and everything abundant.”

That’s the ease. Then there’s the justice. Technology, Andreessen said, is inherently liberatory: “of human potential”; “of the human soul”; and of “what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive.”

By this logic, slowing technological progress would be unjust. Andreessen acknowledges there may be hiccups along the way, but in his view, our only moral option is to proceed at maximum speed to the prosperous, free, and just future that AI and its attendant technologies will provide.

“It is easy for me to imagine,” wrote the farmer-poet Wendell Berry in 2001, “that the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines.”

The vision of humanity behind Andreessen-style paeans to AI belongs to the latter camp. It sees humans not as creatures called to participate in God’s restoration of the world but machines to be optimized and regulated by other, better machines.

Science fiction authors have long warned readers about the risks of the machine world, many sketching its temptations from the same pattern I’ve traced in Andreessen’s manifesto: ease and justice.

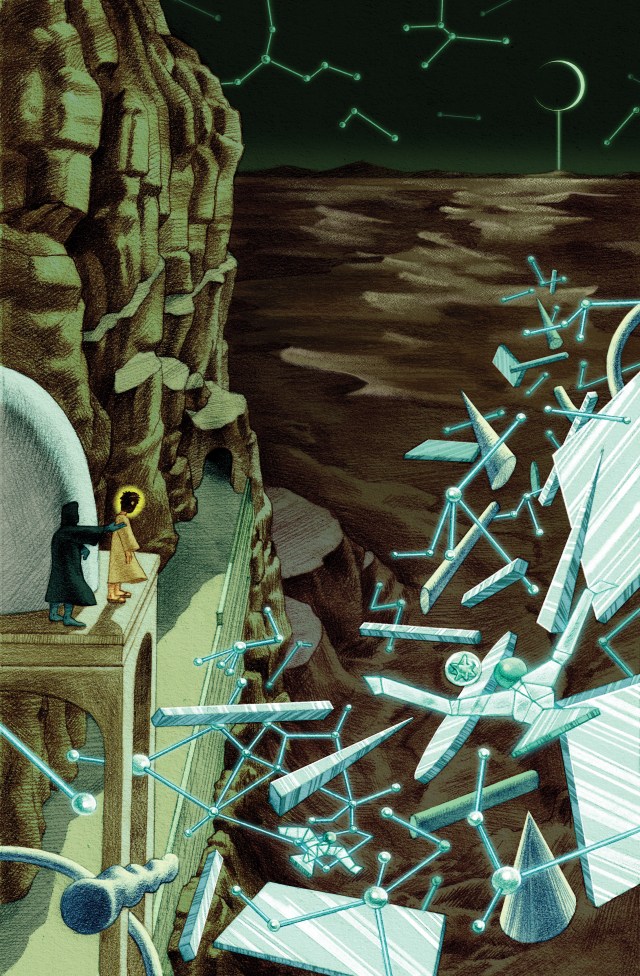

Consider, for example, Paul Kingsnorth’s 2020 novel Alexandria, set in the distant future. Civilization has collapsed after humans made the world uninhabitable. In a last-ditch effort to save the world—or, perhaps, to avoid the work required to live differently—humans have created an AI called Wayland to take over and preserve the planet’s dwindling resources.

But it’s not clear what they’ve really made. By the time the novel takes place, most humans have “ascended” into a disembodied state of existence hosted by Wayland, leaving the Earth to slowly recover. Only a few humans remain in remnant communities, holding out against Wayland’s tempting offer to free them from the sorrows of embodied, primitive life.

The father of this remnant characterizes Wayland as the latest iteration of the primordial temptation: “We made Him so we could live forever. Oldest dream. To be gods.”

The character K is a retainer, a kind of artificial human whom Wayland uses to persuade these few remaining people to leave their bodies behind. K’s proposition to potential customers (or victims) relies on the familiar twofold appeal: Ascending to Wayland’s grid will provide both ease and justice.

One member of the still-human order summarizes K’s appeal as offering “escape from grief, from pain.” K puts it this way: “If your life on Earth is going to be a hardscrabble in dying soil, or a struggle to survive in a lawless megacity slum, why continue it any longer than necessary?” This is the promise of ease.

More subtly, though, K also describes Wayland’s offer as the path of necessary “relinquishment.” Humans destroy the earth through their insatiable appetites, so to save the ecosystem, people must give up their bodies and shift their consciousness to a less energy-intensive medium. This is the promise of justice.

Wayland offers to restore balance to the cosmos, to eliminate suffering and violence, to bring about a rational order. And if violence, as K claims, “is bred into [human] flesh,” then the only way to eliminate it is to liberate humans from their bodies.

Many other sci-fi stories frame the temptations of technology in similar terms. In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s satiric short story “The Celestial Railroad,” preachers like Rev. Dr. Wind-of-doctrine offer “erudition without the trouble of even learning to read” while a steam train ostensibly speeds everyone to heaven.

In Philip K. Dick’s The Minority Report, precogs—mutated humans who can foresee future crimes—are plugged into a computer to do the police’s work for them. In Aldous Huxley’s dystopian Brave New World, a whole host of imagined technologies offer a wraparound utopia. And in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, a disembodied brain promises to “assume all the pain, all the responsibility, all the burdens of thought and decision,” if only the heroes will let it.

What’s fascinating to me about these literary examples is that regardless of the technology they imagine, the appeal is consistent: The means are deemed morally insignificant, and the only relevant consideration is whether the tech makes just and comfortable outcomes easier to obtain.

All of these stories predate ChatGPT, but the temptations in them are far older than computers or the Industrial Revolution. In fact, they eerily recall the Devil’s temptation of Christ in the wilderness in Matthew 4:1–11 and Luke 4:1–13.

Satan had no app to dangle in front of the Messiah, but he too offered justice without effort or pain. He offered Jesus victory without the Cross.

The Devil begins by questioning Jesus’ identity: “If you are the Son of God …” The reality of Jesus’ divinity, the Devil insinuates, hinges on the efficacy of his acts: his ability to turn stones into bread or jump off the top of the temple without being hurt. These are the temptations of ease.

Later in the Gospels, Jesus goes on to perform miracles as impressive as these, but he refuses to accept the Devil’s premise. He refuses to link his divine nature to his ability to do a magic trick. As he reminds the Devil, the highest human good is not merely physical life preserved. It is life sustained by “every word that comes from the mouth of God” (Matt. 4:4).

The final temptation—to rule over all the kingdoms of the world at the price of worshiping Satan—is the temptation to justice. It reveals the deadly division the Devil is trying to introduce between means and ends: He offers Jesus the proper and just end without the difficult means.

Yet as Christ’s ministry and passion make clear, the difficult means are inextricable from the kingdom he comes to inaugurate. Much to the frustration of the crowds who flocked to him, Jesus insisted that his rule must come via his slow, personal ministry and painful death. This pattern repeats throughout his life.

As was made clear when he healed the centurion’s servant from afar or fed the 5,000, Jesus could have performed miracles at scale during his earthly ministry. He could have eliminated all suffering, oppression, and every other effect of the Fall. He could’ve more than fulfilled each promise Andreessen and his ilk now make on behalf of AI, transforming the cosmos into a perfectly functioning machine.

But he didn’t. Instead, the ministry of Jesus was reliably marked by an inefficiency and partiality that can be maddening to those of us who dwell in a machine age.

It was maddening even to many who witnessed it. After Jesus fed the 5,000, the people wanted to make him king by force (John 6:15). They wanted a magical ruler who’d feed the nation and, presumably, trounce the Romans.

But the feeding was the exception that proved the rule. It’s the only miracle included in all four Gospels and the only mass miracle (apart from the very similar feeding of the 4,000). In Luke, Jesus followed it by telling his disciples that he “must suffer many things” and be killed, and that “whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me” (9:21–23).

God’s redemptive presence in a broken creation is not typically an easy poof of justice magically imposed. For us as for Jesus, it is the painful, messy work of personal attention and care.

Why must the kingdom of God come through sacrifice and suffering? Because it is not a matter of equal outcomes and hedonistic plenty; it is God’s presence with us.

As Jesus tells the befuddled Pharisees, “The coming of the kingdom of God is not something that can be observed . . . because the kingdom of God is in your midst” (Luke 17:20–21). Or, as he prays in John 17:3, “This is eternal life: that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent.”

Such an encounter with God and his kingdom is necessarily slow and inefficient. The means of the Incarnation are its ends, and divine presence can’t be automated any more than human presence can be. Jesus must heal person by person, touch by touch.

It is significant, I think, that Jesus never tells us to love the world. God so loves the world, but Jesus tells us to love our neighbor. And the parable of the Good Samaritan, which he tells to identify our neighbors, reminds us how tempting it is to avoid the personal work of love (Luke 10:25–37).

The priest and the Levite could rationalize their lack of concern for the wounded man in terms of efficiency and abstract justice. They had more important work to do, work that would make a bigger impact than helping one man. But our obligation isn’t to maximize our efficacy; it is to care for the sufferer who lies before us, just as the Samaritan did.

When Jesus concluded the parable by telling his hearers to “go and do likewise,” he was commanding us to love our neighbors in the slow, difficult, sacrificial manner of his own earthly ministry.

Our vocation as Christ followers, then, is to follow the path that Jesus trod, to walk slowly with others, to suffer, and—ultimately—to become capable of embodying God’s presence to others. The means are essential to this calling. As Berry reminds us, “Hope lives in the means, not the ends.”

Jesus did good things slowly, and so must we. As the Japanese theologian Kosuke Koyama writes in Three Mile an Hour God, “God walks ‘slowly’ because he is love. If he is not love he would have gone much faster.” Jesus didn’t jet around the world; he walked around Judea. He didn’t proclaim his message instantly across continents; he slowly discipled fishermen and tax collectors. As tempting as ease may be, we must refuse technologies that promise to automate our relationships with the world and with one another.

There’s no economic justification for boiling the sap from the maple trees in my backyard, playing dolls with my daughter, or listening to my first-year students read their essays and engaging with them about their writing. These things are slow, inefficient, and—in some ways—difficult. But they constitute relationships of attention and care between me and those I’m called to love. If I choose ease instead, I forgo the opportunity to have the God who is love abide in me.

Jesus also did good things inefficiently. This may seem blasphemous, but think of the time he spat on the blind man’s eyes, laid his hands on him, and asked him if he could see. The man said people “look like trees walking around” (Mark 8:24). Jesus laid his hands on the man’s eyes again, and then he could see clearly.

Mark placed this faltering healing amid conversations Jesus had with his disciples in which he asked them why, despite all they’d seen, they still understood so little. Then, as if to illustrate the disciples’ flickering recognition of Jesus’ identity, Mark tells in quick succession the stories in which Peter confesses his belief that Jesus is the Christ then rebukes Jesus for saying he’ll die.

Even Jesus’ own disciples—even his right-hand man, Peter—often only dimly perceived who he was. Was Jesus a mediocre teacher, unable to explain himself? Perhaps the point is rather that the disciples—and we—have the opportunity to participate in Jesus’ life and ministry.

The work of the church will be faltering too. We are not precise computers, and that shows when we pray and make music to God, when we do theology, when we try to serve our needy neighbors. But such means are essential to our vocation as divine image bearers. We cannot offload these tasks to ChatGPT. If we try, we’ll fail, no matter how brilliantly the AI performs.

This is not an excuse to be careless or to callously ignore suffering that might be alleviated by judicious use of technology. Still, we should remember that trying to optimize ease and justice often has unintended consequences. Many technologies are useful, but we should be suspicious of any glowing claim that we can use them to magically help others with no effort or virtue on our part.

Finally, Jesus did good things gratuitously. In one of his parables about the kingdom of God, those who begin working in the fields at dawn and those who come at the close of the day receive the same reward (Matt. 20:1–16). That doesn’t seem just. But divine grace—thankfully—flouts human standards. We receive what we could never deserve.

No algorithm can make sense of such incalculable grace. Similarly, when a woman poured a jar of perfume over Jesus, his disciples were indignant at the waste (Matt. 26:6–13). Shouldn’t this perfume have been sold to benefit the poor? Wouldn’t that be more effective altruism? Yet Jesus praised her gesture of love and honor, telling the grumbling disciples that her gratuitous act would be remembered wherever the gospel is proclaimed.

In our age of efficiency, opportunities for gratuity abound. Cook lovely meals for your family even if the kids will scarf it down. Write poems even if no one else will ever read them. As the writer Kurt Vonnegut advised high school students, “Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage, no matter how well or badly, not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming … to make your soul grow.”

If we follow in Jesus’ steps—if we live slowly, do good things however inefficiently, and share the extravagant grace we’ve been given—the temptations of AI, like all false promises and demonic temptations, will grow dim and unconvincing.

The Devil will leave us, and we’ll see the absurdity of his lies. We’ll shake our heads in disbelief that anyone could believe AI will make it easier to discern and enact the truth. And then we can set about the arduous but rewarding work of living as creatures made in the image of God in a world increasingly built for machines.

Jesus resisted the Devil’s temptations of easy justice rather than patient, painful, gracious presence. If we want to participate in his kingdom, we will have to follow his example.

Jeffrey Bilbro is associate professor of English at Grove City College and editor in chief at the Front Porch Republic. His most recent book is Words for Conviviality: Media Technologies and Practices of Hope.