This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

Last Sunday, I took a break from the apocalypse to focus on Christmas.

By “apocalypse,” I’m not referencing the news cycle but, literally, the actual Apocalypse, the Book of Revelation, through which I’m teaching week-by-week Sundays at my church.

The problem is that we are right in the middle of the book, which consists of bowls of wrath, boils and plagues, and a woman riding a beast while drinking the blood of the martyrs. It seemed a little anxiety-inducing to go through all of that and then end with, “So Merry Christmas, everybody!”

Instead, I turned to the Gospel of Luke, to the time of baby Jesus—and found myself right back in an apocalypse.

In the text, right after the account of Jesus’ birth, Mary and Joseph present the infant Christ in the temple. There, they are approached by the prophet Simeon, who takes the baby in his arms.

Some of what old Simeon then says sounds Christmasy enough for our expectations. The baby is “a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for glory to your people Israel” (Luke 2:32, ESV throughout).

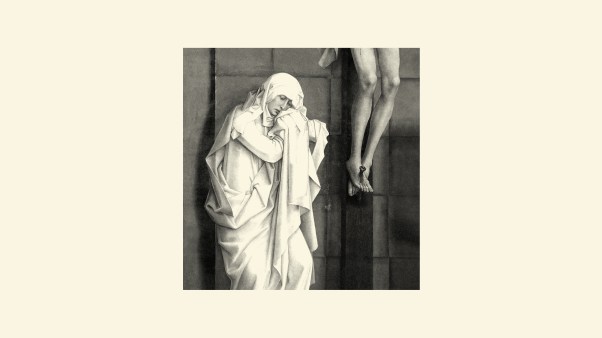

But then he gets dark. Simeon turns to Mary and predicts, “Behold, this child is appointed for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign that is opposed (and a sword will pierce through your own soul also), so that thoughts from many hearts may be revealed” (vv. 34–35).

The word apocalypse, of course, doesn’t hold the same meaning biblically as our pop culture gives it (“scary dystopia”). The word means “unveiling,” a showing of what’s hidden to our perception, a revealing of the way the universe really is. What Simeon saw in that bustling outer court of the temple was that Mary was headed for heartbreak—the kind of soul-tearing heartbreak that would make visible what was really true.

It’s hard to follow “A knife is headed for your heart, lady,” with “Happy Holidays and a Blessed New Year!” The foreboding nature of that word had to be unnerving, if not terrifying. The more I think of it, though, the more I’m convinced that is exactly what we need, all of us, this year.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that adolescents and young adults make up an “anxious generation,” driven by the limbic effects of smartphone and social media ecology. But he also asserts that the anxiety is not limited to any one generation. We all live and move and have our cultural being in a kind of acute anxiety.

By anxiety, here, I don’t mean the clinical, medical condition from which many people suffer. I mean instead the sort of generalized state of worry and tension that seems so heightened in the world around us and within us right now.

In his new book, Consolations II: The Solace, Nourishment, and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, poet David Whyte argues that anxiety describes the way we try to avoid conversing with the things that scare us by worrying about them instead. This kind of constant anxiety, he writes, is actually a defense mechanism for what we are afraid can hurt us.

“Anxiety is the trembling surface identity that finds the full measure of our anguish too painful to bear; constant anxiety is our way of turning away from and attempting to make a life free from the necessities of heartbreak,” he writes. “Anxiety is our greatest defense against the vulnerabilities of intimacy and a real understanding of others. Allowing our hearts to actually break might be the first step in freeing ourselves from anxiety.”

A heightened state of worry feels like doing something, but that kind of hyper-vigilance is exhausting. And it often cuts us off from those things that require vulnerability—the risk of being hurt—to exist: love, affection, compassion, wonder, awe, curiosity, courage, giving of self. Maybe Whyte is correct that what is needed for us right now is not to protect ourselves from heartbreak but to embrace it.

That’s where I realized just how similar the warm, bright Christmas story is to the dark, scary middle of the Book of Revelation. Every Sunday, I remind my church-folk (and myself) that the “scary” parts of Revelation are actually good news. God is pulling back the veil so that what’s hidden is made plain.

The kingdoms of this world are shaky and tottering. The way of Caesar, the way of the Beast, seems right now to “work.” For the first-century church, the word from Patmos is a call to overcome: not by fighting like the Devil against the ways of the Devil but by remaining faithful, enduring through suffering, and waiting on the God of Israel to make all things new.

The Apocalypse doesn’t deny that dangerous days are coming, but it makes clear that they are limited—“a time, and times, and half a time” (12:14). On the other side of the sword that cuts through Mary’s heart at the cross (or those that cut off the martyr’s heads in first-century Rome), there’s a weight of glory that cannot be described adequately with words. We can free ourselves to risk heartbrokenness because a broken heart is the beginning of the story, not the end.

Simeon’s warning is in the context of blessing. He was waiting, by the Spirit, for the “consolation of Israel” (Luke 2:25). He never saw an overthrown Rome. He never saw the murderous house of Herod torn down. He never saw the promise fulfilled of the nations streaming to Mount Zion, with David’s throne occupied by David’s heir. And yet he could say that he could die in peace because he had, in fact, seen “your salvation that you have prepared in the presence of all peoples” (v. 32).

What he saw was this baby. And that was a hidden reality, except for the eyes of faith.

The people bustling through the temple courts didn’t see anything out of the ordinary. Maybe one of them heard the infant Jesus crying and said, “Somebody should tell that woman to keep that kid quiet.” They saw a normal day, filled with the anxieties of life. But Simeon saw an apocalypse—and in it, a world blinded with light.

Every life is filled with anxiety, and every age is too. Sometimes that anxiety feels more acute than at other times, and the future seems more uncertain than before. This Christmas, let’s look beyond the days and years right ahead of us. Let’s see the Light that shines out of Bethlehem, the Light that shines in the darkness, the Light the darkness cannot comprehend or overcome.

Let your heart be broken, but rejoice. All is well in heaven and will be well on earth. Remember the good tidings of great joy. And have yourself a merry little Apocalypse.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.