Of the many letters the apostle Paul wrote, few survived. We have a good deal of his communication to churches as a whole—letters to groups of believers in particular cities. This makes sense. Such letters were read publicly and often; they were copied and disseminated and celebrated as Scripture soon after the ink had dried.

Paul sent a number of letters to individuals as well. To read his biblical writings is to sense that you are glimpsing only a fraction of his relational network and influence. Almost all of those letters have been lost.

But there are exceptions.

It was a tall order for personal letters to ascend to the level of canon. It helped to be bound up with a great figure, a leader of a great community. Timothy, for instance, was a towering second-generation church leader; he was also the bishop of Ephesus, a major city of the Roman Empire and a major Christian center. Titus was a pillar of the Gentile mission and served as the bishop of Crete. Their eponymous letters had huge communities to champion their inclusion in Scripture.

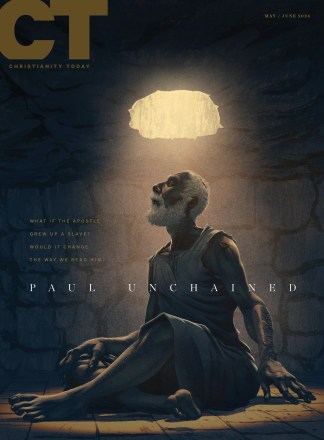

A mystery for the ages, then, is why Paul’s letter to Philemon—the leader of a house church in the minor city of Colossae—survives at all. It’s the most personal letter we have from Paul. It runs only 25 verses.

The letter reveals a story. In it, a man named Onesimus has fled his master Philemon. Onesimus was most likely a household slave, a bondservant high in the pecking order.

To call him a runaway slave is true, though it is misleading for modern readers, who might imagine Onesimus attempting to escape through something like the Underground Railroad.

In fact, some scholars argue that Onesimus sought out Paul but planned to return to his master. Steven M. Baugh, an emeritus professor of New Testament at Westminster Seminary California, wrote, “It seems most likely that Onesimus intentionally ran away from Philemon and ran to Paul in order to seek his intercession on his behalf with Philemon over some quarrel between the master and slave. This letter is Paul’s intercession.”

It’s hard for us today to understand why Onesimus might want to return to enslavement. But the explanation is simple: If Onesimus has an important position helping his wealthy owner, he would not quickly trade it for a life as a poor peasant.

“Slaves belonging to the households of the wealthy or moderately wealthy in some ways lived a better life than the free poor of the city,” wrote historian James S. Jeffers in The Greco-Roman World of the New Testament Era. “Unlike the free poor, such slaves normally were assured three meals a day, lodging, clothing and health care.” Many slaves, Jeffers adds, “were better educated than the freeborn poor.”

That said, the traditional and most common interpretation of Onesimus’s motives is that he took Philemon’s money and had no intent of going back.

And there would have been plenty of money. Many slaves with organizational skills and business acumen were charged with overseeing the businesses of their masters. These were known as oikonomos, or stewards (the source for our word economy).

Philemon, a wealthy businessman and Christian convert of Paul’s, lived in Colossae. He would have had a number of slaves to assist in his ventures. Due to the risk of robbery along the route to major trade centers, men like Philemon would not travel with their goods themselves. Instead, they would entrust the task to reliable slave stewards like Onesimus.

But in this case, instead of returning to Philemon with his money, Onesimus may have pocketed the cash and hopped on a ship to Rome. And soon, we find him at Paul’s side, serving him in prison and becoming a follower of Christ under Paul’s instruction.

Whether he fled to seek Paul or happened to hear of him through the local Christian community in Rome, we can’t be sure. But it is strange that a runaway slave would spend so much time around a religious figure under suspicion, serving house arrest, surrounded by agents of the state.

Why did Onesimus take the risk and come to Paul? It’s as if he knew something about Paul that we’ve forgotten.

In the decades before the birth of Jesus, a spirit of zealotry hung thick in the air in northern Israel. The land was a hotbed of resistance and uprisings against Rome—sometimes armed revolts, sometimes theft from Roman depots where the odious Roman taxes were stored.

But Rome was no rookie. Keeping people subjugated was a wicked art, and the empire had centuries of practice.

Insurrectionist commanders were executed by horrific means such as crucifixion or impalement. And Rome knew it was not enough to cut off the head; to snuff out rebellion, whole communities had to be dealt with.

So—as the ancient historian Josephus tells us—Rome began sacking entire rebel villages, selling their inhabitants as slaves on the many slave markets. Slave dealers during this era often followed behind Roman legions on military campaigns, gathering human spoils and filling Roman coffers.

One of the villages in Galilee would especially bedevil Rome in the hundred years surrounding Christ’s resurrection. It was the far northern village of Gischala.

After some infraction there in the final years B.C. or early years A.D., the details of which are forgotten to history, the Romans rounded up the people of Gischala, carted them away, and enslaved them.

If the early church’s memory is correct, Paul’s parents were among them.

In A.D. 382, the pope commissioned a young and astonishingly bright scholar named Jerome to update the archaic Latin Bible. Scholars who knew Greek were a dime a dozen, but Jerome was one of the few with mastery in Hebrew as well as Greek.

Two decades later, working from a monastery in Bethlehem, he finished the monumental task of the Vulgate, the world’s most influential Bible translation. He also managed to write, among other works, four commentaries on Paul’s letters.

In Jerome’s commentary to Philemon, he records the early church’s memory of Paul:

They say that the parents of the apostle Paul were from Gischala, a region of Judaea, and that, when the whole province was devastated by the hand of Rome and the Jews scattered throughout the world, they were moved to Tarsus a town of Cilicia.

Another translation of Jerome’s commentary may put the Latin fuisse translatos more accurately. It says Paul’s parents “were taken to Tarsus”—that is, taken against their will.

Some people have speculated that Paul’s ancestors were opportunists. Maybe they left Israel because leatherworking and tentmaking was better business in a major Roman hub like Tarsus.

But that’s not what the early church said.

This “taken” euphemism means that Rome dealt with Paul’s parents the way they almost always dealt with defiant people. According to German scholar Theodor Zahn, they were “taken prisoners of war” and sold as slaves in Tarsus. Paul may have been a child then, Zahn says, or he may have been born partway into his parents’ slavery obligation.

Roman slavery was not the same as American chattel slavery. “Roman citizens often freed their slaves,” Jeffers wrote. “In urban households, this frequently happened by the time the slave reached age 30. We know of few urban slaves who reached old age before gaining their freedom.”

According to the classicist Mary Beard, many contemporaries saw this slavery-to-citizenship path as a distinguishing feature of Rome’s success. She writes, “Some historians reckon that, by the second century CE, the majority of the free citizen population of the city of Rome had slaves somewhere in their ancestry.”

This is why many Bible translations have chosen to use the term servant or bondservant rather than slave. Enslavement was certainly a gross affront to human rights. But New Testament slavery was not the kind of slavery North Americans often think of. Roman enslavement generally had an end. And in many cases, it even created opportunities for social advancement, especially for children of the enslaved.

A few centuries after Jerome, Photios I, the bishop of Constantinople, walked around his famed library and pulled down some volumes and documents that have since been lost in the sands of time. Only his letter citing those documents remains. Drawing not from Jerome but from another early church source historians still haven’t identified, he wrote,

Paul, the divine apostle … who had laid hold of the Jerusalem above as his fatherland, had also as his portion the fatherland of his ancient ancestors and physical race, namely Gischala (which is now a village in the region of Judea, being called of old a small town). But because his parents, together with many others of his race, were taken captive by the Roman spear and Tarsus fell to his lot where he was also born, he gives it as his fatherland.

Photios has Paul born in Tarsus to his enslaved parents. Now, just because a tradition exists doesn’t mean it’s true. Plenty of traditions don’t square with Scripture and must be left aside.

But not this one.

Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, a Pauline scholar and New Testament professor at the École Biblique in Jerusalem, wrote that the “likelihood that he or any earlier Christian invented the association of Paul’s family with Gischala is remote. The town is not mentioned in the Bible. It had no connection with Benjamin. It had no associations with the Galilean ministry of Jesus.”

Translation: If you’re going to invent a legend about Paul’s background, you’re going to come up with something cool. You’d put him in an important place, with a story that cements his heritage in the biblical narrative. Not in an obscure town that doesn’t even appear in Scripture.

As historical church traditions go, this is about as reliable as they get. German scholars like Zahn and Adolf von Harnack refer to this type of detail as unerfindbar—roughly, unfathomable, unless it’s true. English translations of this term clarify it as “too definite to have been invented.”

One of the great conundrums of Pauline scholarship is why few experts in the English-speaking world talk about this. Douglas Moo, a leading Paul scholar at Wheaton College, said in an interview, “I have run across very few books on Paul that even mention it.” In his biography of Paul, N. T. Wright casually remarks that this is a “later legend.”

But it’s hardly a legend, and it’s scarcely later.

Scholars of Jerome and Origen, another early church father, agree that Jerome’s statement about Paul’s parents, written in A.D. 386, is not original. In fact, little from Jerome’s commentary is original.

Ronald E. Heine, an Origen scholar at Bushnell University, said that “Jerome is basically translating Origen.” Caroline Bammel, an early church historian at Cambridge, put it more bluntly when she wrote that Jerome’s work in his commentaries is “largely plagiarized from Origen.”

Origen’s Philemon commentary, like much of his work, has been lost. But through Jerome’s translations—or appropriations—of other Origen commentaries, scholars are confident it comes from Origen. “In this commentary we have the exposition of Origen dressed in the garb of Jerome’s Latin,” Heine wrote.

This places the tradition about Paul’s heritage not in Jerome’s time but in Origen’s, the early 200s. And Origen was writing from Caesarea, next door to Galilee and in a city where Paul spent two years (Acts 23:23–24; 24:27). The elderly storytellers around him who kept the oral tradition would have grown up under the leadership of the second and third generations of the church.

Contrary to being some later legend, this is the “earliest known exposition of the Epistle to Philemon,” Heine writes. “In all likelihood, [it] represents the first commentary ever written on the epistle.”

In the German academy, the idea that Paul was a manumitted slave has been a live conversation for 150 years. Eminent 20th-century scholars like Von Harnack and Zahn, along with Martin Dibelius, gave Jerome’s story credence.

Plenty of other German scholars “take seriously the assertion that Paul’s parents came from Galilee,” wrote theologian Rainer Riesner, who teaches today at the University of Dortmund.

Some even go so far as to pinpoint which Galilean rebellion may have led to the enslavement of his parents—the uprising in 4 B.C., when Varus, the Roman governor of Syria, burned entire cities and crucified 2,000 people. In Galilean cities like Sepphoris, Josephus wrote in the Antiquities of the Jews, they “made its inhabitants slaves.”

If this is correct, the fact that Saul of Tarsus shows up in Jerusalem two decades later as a young teenager makes perfect sense. When Paul told the commander in Acts 22:28 that he was “born” a Roman citizen, that word, gennao, can refer to birth or adoption. Freed Roman slaves were often adopted into their master’s family and given a Roman name and citizenship.

This also explains why he has the name Paul, a very Roman name that no Pharisee would give their very Hebrew child.

Contrary to popular thought and pulpit references, Saul does not take on the name Paul after becoming a follower of Christ. The name Saul is with him from the beginning and continues to be used after his conversion (Acts 11, 13).

In Hebrew contexts, he uses his Hebrew name, Saul. In Greco-Roman contexts, he uses the cognomen (the third part of a Roman name) Paullus, which he would have inherited from the family that owned him.

Though he could have inherited the name Paullus from any number of Roman families, there was one particularly famous family with that name—the Aemilian tribe, according to 20th-century classics scholar G. A. Harrer. We cannot know for sure, but Harrer speculates that if Paul’s owner came from that tribe, his Roman name could have been L. Aemilius Paullus, also known as Saul.

Wherever the family name originated, Riesner said in an interview, Paul’s father “was manumitted by his Roman master and automatically earned [Roman] citizenship.”

It’s easy to forget how strange a person Paul is. He and Luke seem to tell such different stories of Paul’s life that it’s stumped some scholars.

In Acts, Luke paints a picture of Paul as a Roman and Tarsian citizen, at home in the Hellenistic Jewish world’s lax adherence to the ancient customs. Paul, however, refers to himself elsewhere in very Jewish terms: “a Hebrew of Hebrews”; Aramaic-speaking; “of the tribe of Benjamin”; a Pharisee; a zealot (Phil. 3:5–6).

If you didn’t have the Book of Acts, you’d likely presume Paul was from Galilee or Jerusalem based on the way he talks. After all, “a person did not become a Pharisee outside Palestine,” Riesner writes in Paul’s Early Period.

It was virtually unheard of for someone to be both a Galilean zealot Pharisee and a Roman citizen in Tarsus. For instance, some might claim one could not be a “Hebrew of Hebrews” and a Hellenistic Jew. But that’s precisely what Paul was.

Paul was not a Greek-speaking Jew who had lost his language, lost his culture, and was living in the lap of Roman luxury.

Then as now, there was a strong differentiation between Jews who lived in and defended their homeland and those who made a more comfortable life elsewhere. Paul intentionally signaled that he was rooted in and fiercely committed to his heritage.

At the same time, though, Paul was an oddity among Romans, because Hellenized Jews rarely spoke Aramaic. Paul’s fluency in the language is so significant that it is the climax of the scene recorded in Acts 21 and 22.

In the second half of Acts 21, Paul’s presence in the Jerusalem temple causes an uproar. He’s mistaken for an Egyptian false prophet who had deceived many people a few years earlier, and a mob becomes so violent that Roman soldiers have to physically carry Paul away.

But Paul, in his native and educated Greek, addresses the Roman commander. Hearing Paul’s Greek, the commander realizes they have the wrong guy; this is clearly no Egyptian.

Paul then asks if he can address the mob.

He mounts the steps and begins speaking to the people—in Aramaic, the language that had filled their ears as infants bobbing on their mothers’ shoulders. “When they heard him speak to them in Aramaic, they became very quiet,” Luke says (22:2).

Just as fourth- and fifth-generation Americans do not normally speak the languages of their immigrant ancestors, it was unheard of for diaspora Jews to speak Aramaic. That was the language of Israel. Unless Paul’s family had been very recently removed, he would not have been a native speaker.

There’s another inconsistency on Paul’s résumé: Paul had moved to Jerusalem as a teen to study with Gamaliel, a renowned Jewish teacher (5:34). This was not an honor that ordinary diaspora kids or Hellenistic Jews usually received. But if Paul’s parents were zealots, forcibly transplanted to Tarsus, then his pedigree might have marked him as special.

“Many modern scholars strongly doubt that a pious Jew like Paul could be a Roman citizen,” Riesner told me. Reconciling the Pharisee, Hebrew of Hebrews, Aramaic-speaking zealot Paul with the Roman citizen, globetrotting, Greek-speaking Paul seems impossible. Unless, that is, we consider the early church’s recollection of Paul’s upbringing as a child in an enslaved family.

“The manumission of Paul’s father solves these problems,” Riesner told me.

Riesner comes from a long line of German scholars who have thought the same. “The great liberal Adolf von Harnack and the great conservative Theodor Zahn” were both “strong defenders” of this tradition, he told me. They did not even agree on the Resurrection, but they agreed on this.

So why aren’t more Christians in the English-speaking world talking about this?

One theory is simply that German scholars of the 20th century read Greek and Latin much better than current American or British scholars do. By the time those Germans began their posts at elite universities, they could take up Homer or Origen in Greek, or Jerome in Latin. They could read not just for research but for fun.

New Testament studies in the English-speaking world, in contrast, tends to emphasize only the corpus of New Testament Greek. Many New Testament researchers simply cannot read Homer—or Origen, for that matter. Thus, after World War II, when the center of scholarship shifted from German-speaking to Anglophone universities, this part of the Paul conversation may have gotten lost in translation and in the flipping of dictionary pages.

“The church fathers grew up quickly here in America,” Heine, the Origen scholar, told me. It’s only very recently that patristic studies have received proper attention, he said.

Whatever the exact reasons, some of our scholarship clearly suffers from a lack of familiarity and trust for the work of the early church.

One of the words Paul sometimes uses to identify himself as a young man is zealot (usually translated in places like Galatians 1:14 as “zealous”). We have generally taken this to mean that he was full of zeal or “on fire for God.” But there’s good reason to believe that Paul was identifying himself with the particular Jewish sect violently opposed to anyone infringing on Torah observance, which included Romans.

If that’s so, what kind of zealot was Paul before he encountered Christ?

Through his experience with slavery, Paul had learned that Rome wasn’t altogether evil—the empire had conferred citizenship upon him, after all. Paul retained the zealot perspectives of his upbringing, but they had changed. No longer directed against Rome, his zealotry was for his ancestral traditions. His persecution of the Christians was an expression of that zealotry.

Even after his conversion, Paul appears reluctant to reveal his Roman citizenship in front of fellow Hebrews, who may still associate him with the zealots. He puts up with beatings that he could have prevented by invoking his citizenship (Acts 16:16–40). As the Roman philosopher Cicero wrote, “to bind a Roman citizen is a crime, to flog him an abomination, to slay him almost an act of parricide.”

It’s only when there are few or no Jewish onlookers that Paul seems willing to play his citizenship card. In the scene in Acts 22, Paul is sequestered in the soldiers’ barracks when he shocks them with the news.

It’s possible that not until Paul’s later years would many Jerusalem apostles have known about his citizenship. It’s hard to be a great Jewish leader and also a citizen of the empire oppressing your people.

But if you were raised a slave in a Roman city and then freed, it makes good sense how you could be both a citizen of the empire and not entirely warm toward the empire.

Zealots practiced their zealotry in different ways. Some extremists took to assassinating political figures, Romans, or Rome-sympathizing Jews. Others engaged in more specific religious violence, such as abducting uncircumcised Hellenistic Jews and circumcising them by force.

For those of this mindset, their hero was Phinehas, the grandson of Aaron. Just as the Israelites were about to enter the Promised Land, Phinehas had burned with anger over men who were taking Moabite women and joining in their fertility cult worship. In Numbers 25, he fetched a spear and followed a man and his Midianite lover into a tent, stabbing them both through with a single thrust and turning away God’s wrath.

In his biography of Paul, N. T. Wright explains, “When Paul the Apostle describes himself in his earlier life as being consumed with zeal for his ancestral traditions, he was looking back on the Phinehas-shaped motivation of his youth.”

Phinehas is young Paul’s hero. Paul is desperate to deliver the Jewish people through the same kind of violent zeal.

In the pages of Scripture, then, it’s little coincidence how we meet him.

In the budding messianic movement later called Christianity, there was a standout preacher named Stephen. Not only could he preach, but he helped lead a group serving Hellenistic Jewish widows whose needs went unmet because they were seen as second-class compared to Hebrew widows (Acts 6). In young Paul’s mind, Stephen was desecrating Jewish notions of monotheism and of violating the rabbinic traditions, just as Jesus did.

If the zealots were looking for a target, Stephen would do just fine.

Paul then incites the era’s equivalent of a lynching. It’s not led by local Hebrews but by “members of the Synagogue of the Freedmen (as it was called)—Jews of Cyrene and Alexandria as well as the provinces of Cilicia and Asia” (6:9).

As Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary scholar Eckhard J. Schnabel wrote in his Acts commentary, “The ‘freedmen’ … were Jews who had been manumitted as slaves by their owners or were the descendants of emancipated Jewish slaves.”

If the early church is correct about Paul’s parents, then, whether Paul was born to a freed father or was born into slavery and later freed, Paul would have been considered a freedman.

The members of this synagogue of freedmen go on to produce false witnesses against Stephen in order to drum up a case against him (v. 13).

It would be strange for a “Hebrew of Hebrews” Jerusalem insider to work exclusively with former slaves in setting up this ruse. If Paul is an important upper-crust local, his association with former slaves also makes little sense. Pulling off bearing false witness required a tremendous level of trust among a group. Any leak and the schemers themselves would face the punishment they were seeking for their victim (Deut. 19:16–21).

It makes much more sense if this synagogue of freedmen—many of whom were from Cilicia, the capital of which was Paul’s hometown Tarsus—were close friends and compatriots who saw the world as Paul did.

“Luke might assume that Paul belonged to this particular synagogue,” Riesner writes.

And so very possibly, Paul, the freed slave, is surrounded by freed slaves from his same region. He stands in the inner ring, leading these conspirators in the first Christian martyrdom. He then makes plans to pursue and destroy budding messianic communities across the Roman Empire.

First on the list? Damascus.

Of course, en route, Paul is confronted by a heavenly visitor, knocked down, and blinded for three days (Acts 9). The world has not been the same since.

Not only does the early church’s telling of Paul’s backstory better explain Paul, but it also better explains the way he talks.

We take it for granted that Paul writes the way he does. We take it as normal. But if the rest of the New Testament can serve as a guide, it’s not.

Everyone is formed by their background. Our vocabularies and mental toolboxes betray the evidence of our upbringing. And Paul is obsessed with the language of slavery. In his writings, he speaks constantly of it: Of bondage. Of freedom. Of adoption. Of shackles. Of exodus. Of citizenship. The two most common openings to Paul’s letters are “Paul, an apostle of Christ” and “Paul, a slave of Christ.”

Meanwhile, the entire rest of the New Testament rarely uses slavery language. Paul only wrote a quarter of the New Testament by word count, but simple word searches show that slavery themes occur disproportionately in Paul’s material.

And there are subtle references tucked among the more obvious ones. At the end of Galatians, for instance, Paul says, “From now on, let no one cause me trouble, for I bear on my body the marks of Jesus” (Gal. 6:17).

It’s easy to assume that Paul is referring to the scars he acquired through the many beatings he endured. The problem is, Galatians is likely Paul’s earliest letter, according to Wright. Pauline scholar Richard N. Longenecker also argued that Galatians was written very early in Paul’s ministry, “before the ‘Council’ at Jerusalem.”

Those whippings, beatings, and stonings—and their resulting scars—would come later. So what marks is Paul talking about?

There’s also something funny about his word choice.

There are many words in Greek for scar; you might choose any number of them before using the one Paul does here, the Greek word stigmata.

If you can will yourself to forget the later medieval Latin meaning of the word, stigmata in Paul’s day, according to Johannes Louw and Eugene Nida’s lexicon, meant “A permanent mark or scar on the body, especially the type of ‘brand’ used to mark ownership of slaves—‘scar, brand.’”

If Paul were born into a slave family, he would have had a brand pressed into his flesh to mark his owner. Paul is emancipated by the time we’re introduced to him, but the brand would have remained. And Paul, who’s a master at interpreting the old through the lens of the new in Christ, is able to reinterpret even this.

Paul’s identity is still that of a bondservant. Only now, he knows who his true master is. Paul, a slave of Christ.

These sorts of examples are not accidental. Slave analogies are the background scenery that fills Paul’s imagination.

In his book Reading While Black, Wheaton College professor Esau McCaulley recounts the story of Howard Thurman:

The story is often told of Howard Thurman’s experience of reading the Bible for his grandmother, a former slave. Rather than have him read the entire Bible, she omitted sections of Paul’s letters. At first he did not question this practice. Later he works up the courage to ask her why she avoids Paul:

“During the days of slavery,” she said, “the master’s minister would occasionally hold services for the slaves. Old man McGhee was so mean that he would not let a Negro minister preach to his slaves. Always the white minister used as his text something from Paul. At least three or four times a year he used as a text: ‘Slaves, be obedient to them that are your masters…as unto Christ.’ Then he would go on to show how it was God’s will that we were slaves and how, if we were good and happy slaves, God would bless us. I promised my Maker that if I ever learned to read and if freedom ever came, I would not read that part of the Bible.”

Many believers today struggle to read Paul because of this troubled legacy of interpretation. Throughout American history, many misread and then weaponized Paul against the oppressed. Some still do.

Though Christians would eventually come to end slavery in the Roman empire and lead the charge for abolition in the West, slave owners the world over also backed their ideology with the Bible—leaning especially on Paul’s words.

But Paul was neither a proponent of slavery nor an abolitionist, despite efforts to use his letter to Philemon to make him out as one or the other. In truth, neither option was available to him.

It’s difficult for modern readers to understand that in the Roman Empire of Paul’s time, abolitionist thought was virtually nonexistent. According to Jeffers, “No Greek or Roman author ever attacked slavery as an institution.”

It was a given that slavery would always exist. Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, “All available evidence suggests that even those ancients who were born slaves and later freed, several of whom have left us very beautiful texts, envisioned servitude in the same light.”

Instead, the first Christians had their minds almost exclusively fixed on the Second Coming, which they believed was imminent. There wasn’t time to reform entrenched Roman injustices.

And even if early Christians had harbored abolitionist ambitions, at the time of Paul’s ministry, Christians numbered fewer than 1 in 1,000 people in the Roman Empire. They were held in suspicion and persecuted. Their leaders were regularly executed—including, eventually, Paul. Christians had no voice. Not yet.

But make no mistake. If Paul could accomplish no great things, he could accomplish small things with great love. And those small things would turn the world upside down. “Paul’s revolution,” Scot McKnight writes in his commentary on Philemon, “is not at the level of the Roman Empire but at the level of the household, not at the level of the polis [city] but at the level of the ekklēsia [church].”

As British scholar F. F. Bruce put it in his biography of Paul, the Letter of Philemon “brings us into an atmosphere in which the institution [of slavery] could only wilt and die.”

It’s hard to imagine a time when bondservice was such a given that not a single writer of the era would directly challenge it. But perhaps more than any ancient writer, Paul salted the soil of slavery.

When we ignore the memory of the early church, we ignore that Paul was possibly the least likely person to condone slavery. His parents were slaves. He may have been one, too.

What if Onesimus knew this? The runaway bondservant may have traveled more than 1,000 miles to seek the help of a man he suspected would especially understand his predicament.

The apostle claims he is sending Onesimus back as if he were his own “heart” (Phm. 1:12). The word used here is not the customary Greek word kardia. Instead, Paul used the word splanchna, denoting one’s innermost feelings. Joseph Fitzmyer comments “Paul sees Christian Onesimus as part of himself.” The use of splanchna in this letter “shows how personally Paul was involved in the matter.” Why was Paul so personally involved? He knew what it was like to walk in Onesimus’s sandals.

When Paul entrusts his letter to Onesimus and sends him back to his master Philemon, the apostle both gently pleads and forcefully charges Philemon to receive Onesimus back “no longer as a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother” (v. 16).

Paul further tells him to welcome Onesimus back as if he were welcoming Paul himself. “If he has done you any wrong or owes you anything, charge it to me,” he says. “I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand. I will pay it back—not to mention that you owe me your very self” (v. 18–19). Just a few verses later, he not-so-subtly hints that once he gets out of prison, he’ll be swinging through to stay with Philemon. He will know whether Philemon did the right thing.

This is unheard of in the ancient world, to welcome a runaway slave as one would welcome one of the great leaders of a movement.

It’s this radical equality that made Christianity such a threat to the rulers. No contract, class, or caste could threaten the image of God on every human being. As Paul reminded bondservants and owners alike, they were equals before God. “You know that both of you have the same Master in heaven, and with him there is no partiality” (Eph. 6:9, NRSV).

Sadly, Paul was executed by the Roman emperor Nero before he could make it back to Colossae. Maybe we’ll never know what happened to Onesimus or how Philemon responded to that letter.

But it’s possible the outcome has been hiding in plain sight by the very fact that the letter survived.

Over the past century, scholars have concluded that the characters and stories included in the Bible are not chosen simply randomly or because they are compelling. As John reminds us, “Jesus did many other things as well. If every one of them were written down, I suppose that even the whole world would not have room for the books that would be written” (John 21:25).

According to Cambridge biblical scholar Richard Bauckham, the characters that made the cut did so because they were recognized by the early church.

The Gospels overwhelmingly include details of the figures who were still leading the church some 30 years into its existence. It’s one reason why Mary the mother of Jesus, who tradition holds lived on for decades in Ephesus, gets so much airtime in Scripture and her husband Joseph, who died early, has not a single word of dialogue. There is a kind of survivor bias in Scripture.

As influential as Stephen may have been, his story mostly serves to introduce the bigger story of Paul, who shapes the growing church for many years.

Peter’s betrayal and reconciliation to Jesus is one of the very few stories included in all four Gospels, very possibly because Peter was well known by the young Christian community and remained in it for decades, probably often recounting the tale.

Of the many personal communications from Paul that have probably been lost, why then was the letter to Philemon preserved? Why was this letter in particular kept, read publicly, copied by hand, and disseminated all over the known world?

Just as the Gospels seem to favor the stories of those still known in the Christian communities, and as Paul’s surviving personal letters were tied to leaders of large communities, we have strong reason to infer the same here. Philemon, Onesimus, or both may also have been well-known and influential in the early church.

We know from the letter that Philemon was part of a house church in Colossae, a minor city in modern-day Turkey. It’s doubtful that churches everywhere would have taken much interest in the origin story of a small house-church host who had to be admonished by Paul.

But in nearby Ephesus, the region’s capital city and one with a large Christian community, there is a story that would make the letter worthy of rescue. Of celebration.

Timothy was the first bishop of the churches of Ephesus. Early church historians record that he was martyred by the Roman emperor, just as his mentor Paul had been.

But before that, he had time to build a roster of pastors. One of Timothy’s pastors was known as a true shepherd of shepherds. A pastor of pastors. The kind who visited those in prison and cared for orphans and widows in their distress (James 1:27). He seemed to truly understand the plight of the marginalized, as if he himself had once been marginalized.

When it was time to choose a new bishop after Timothy’s martyrdom, church tradition and many modern scholars agree, there was an obvious choice. The Ephesian church chose the shepherd of shepherds.

This man served wonderfully for decades. And in his old age, he too was killed by Rome.

His name was Onesimus.

Mark R. Fairchild is a retired professor of Bible and religion at Huntington University and a Fulbright Scholar. His forthcoming book on Paul will release in 2025 with Hendrickson Publishers.

Jordan K. Monson is an author and professor of missions and Old Testament at Huntington University.