For some time now, I’ve been intrigued by who whispers what behind closed doors.

When I am with right-wing groups, inevitably someone will look around to make sure we’re alone before voicing concern about the increasing extremism demanded by “the base”—especially regarding white nationalism.

When I’m with a left-wing crowd, someone will quietly shrug at the announce-your-pronouns gender ideologies—the kind that demand saying “pregnant people,” for instance, instead of “pregnant women.”

Debates on these issues are important, but what interests me most is that these concerns are never spoken publicly—only in safe spaces away from the tribes.

Michael Schaffer at Politico summed up this political predicament with a headline: “Liberal Elites Are Scared of Their Employees. Conservative Elites Are Scared of Their Audience.” As Schaffer put it, “On the left, they’re afraid of disaffected underlings organizing on Slack. On the right, they tremble before enraged strangers yelling at TVs.”

People on the left widely distributed an article by Ryan Grim from The Intercept showing progressive organizations in gridlock because young staffers insist their leaders take a policy stance on carbon emissions or Middle East diplomacy.

On the other side, a longtime conservative Republican leader told me he left politics because he was tired of the old men eating breakfast at Hardee’s screaming at him for not supporting Donald Trump enough.

Recent years have shown us this kind of fear is not limited to “elites.” The performatively outraged people those elites are trying to appease often feel just as scared—fearful of not proving themselves ideologically pure enough to stay in the in-group.

Cultural analysts have termed this phenomenon “audience capture.” Once a person offers “red meat” (or vegan soy) to the audience they want to attract, they ultimately end up being captured by that audience—and then expected to continue attacking who or what is deemed the other side. This is how people become hacks. They don’t say what they actually think; they say what they’re supposed to think—and they do so as radically as the mob demands.

This trend would be bad enough if it were limited to institutions or elites. But in a time where virtually everyone has an audience—if only via a social media feed—the results can be demoralizing. The expertise and authority upon which every institution depends—from a Sunday school class to a democratic republic—are swept away.

The stakes are higher for the church. Jesus walked away from audience capture—the demand, for instance, to let the crowd make him a rival king of Caesar (John 6:15) or to be defined by expectations for a continual supply of food (v. 26).

Instead, Jesus spoke of the very thing his followers least wanted—the “difficult” teaching that “unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (v. 53, ESV throughout).

If he had done otherwise, you and I would not be here. The words he spoke were Spirit and life (v. 63), not the talking points of another Galilean would-be guru or demagogue.

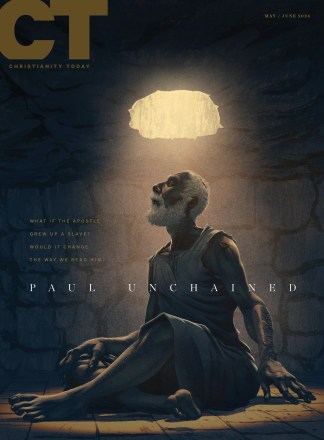

Likewise, the apostle Paul refused to “practice cunning or to tamper with God’s word, but by the open statement of the truth” he would “commend [himself ] to everyone’s conscience in the sight of God” (2 Cor. 4:2).

Evangelical Christianity should be an “anti-elitist” movement. We believe that the gospel and the Bible—not a magisterium—form and reform the church. We seek no one’s permission to preach the Word of God and we believe God will gather his people. But the shadow side of this kind of freedom is the temptation to think that consensus is a sign of truth, or that popularity is a sign of success.

Once we’ve been captured by audience—poll-testing what “itching ears” (2 Tim. 4:3) will hear and remaining silent on what they won’t—we are no longer speaking before God. People will discern who’s carrying a message from someone else and who’s saying what they’re expected to say.

Those who are captured by their audience cannot deliver the real good tidings of great joy—which can’t be market tested and manufactured but can only be spoken, heard, believed, and confessed.

Some fear their audience; others, their constituency. But we should fear only God.

Russell Moore is editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.