I find much of what’s written today about gender to be oddly abstract and otherworldly. Debates about gender in the church and culture often orbit around questions relating to authority and submission or whether gender is a binary or a spectrum.

And while such discussions may be valuable to a certain extent, they don’t go very far in addressing the roots of the gendered pain we experience in this “present evil age” (Gal. 1:4). Offering abstract principles ignores the particulars of a person’s life—which are often what cause the greatest pain.

This is why, whenever we think theologically about gender, we must be careful not to draw a clear line between the theoretical and the personal. A theology of gender that does not witness to the open wounds of God’s people remains detached and ethereal, unable to speak the right words of hope to a gendered world longing for flourishing.

I learned this lesson firsthand. After publishing an article about gender in the resurrection, I heard from a faithful and thoughtful intersex individual—someone who was born with diversities in sex development—who asked if she would be resurrected as her current gender or not. This was an important question for this person, because the hope of resurrection meant something to her as a believer.

For us, “a new heaven and a new earth” (Rev. 21:1) is morally normative—indicating the way God intends the world to be—unlike the fallen state of our earth today. Rather than some distant situation that bears no connection to our ordinary lives, the eschaton defines what a flourishing life ought to look like. Eschatology deals with questions like “What does a life free of the destructive forces of sin look like?” “What does God’s justice look like when it has fully blossomed?” “What would it feel like for us to truly flourish?”

I tell my students that thinking about the new creation is kind of like that kids’ activity where you “spot the differences” between two pictures. By identifying the disparities between the way the world is now and the way it ought to be—and will be someday—we can learn how to act today.

If eschatology gives us an idea of creation as it ought to be, then the resurrection gives us a sense of our bodies as they ought to be. This means that whatever we say about our bodies in the resurrection influences what we say about our bodies now.

It is no coincidence, therefore, that individuals for whom gender is a point of pain and difficulty often reach for the language of resurrection to describe what it feels like to be delivered from that pain. By associating gender with resurrection, we instinctively conceive of how gender should be—which, in turn, testifies to the ways our paradigms for gender have been broken and distorted by sin.

Christians affirm that when our bodies are resurrected in the new creation, they will become all they were created to be and our hopes for holistic healing will be fulfilled. The problem is, we have different understandings of how the resurrection is meant to cure the brokenness in our gendered bodies.

If someone’s arm is bitten by a venomous snake, there seem to be two options: Amputate the poisoned limb, or extract the venom. While both yield the same result—saving the person from a life-threatening toxin—they achieve it in starkly different ways: one by removal, the other by renewal. Likewise, how believers envision the resolution of our gendered pain often boils down to whether our genders are removed or renewed in the resurrection.

To ask whether our bodies will be gendered in the new creation is to ask what the ultimate healing and flourishing of our God-given genders might look like.

While it may seem like this question would only have been relevant in recent decades, it turns out it’s been asked for centuries—and I believe the way we answer it has real-world significance for how we understand what a flourishing gendered life looks like today.

There is a long and impressive lineage in Christian history and contemporary theology that says the best way to envision the redemption of our gender is to picture its removal. Drawing on figures like Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Maximus the Confessor, this strand argues that we will not be gendered when we are raised.

According to this view, some aspects of humanity are part of God’s image, while others are shared with nonhuman creatures—and this includes gender. In fact, they say, gender was an attribute given to us only because God foreknew humanity would sin. It was meant to sustain us only until the restoration of creation. Therefore, attributes like gender, race, and disability, which they believe cause us the most pain and struggle in this life, will not remain in the resurrection.

Foundational to these thinkers’ arguments—and those of contemporary theologians who have retrieved their line of thought—is Galatians 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (emphasis added). True creation is creation in Christ—and in Christ, they infer literally here, there is no male and female. Even if gender was originally part of the old creation, they argue, it’s not the right kind of creaturely attribute to persist into the new creation.

Some recent theology has gone so far as to reconsider what we think our bodies were created to be to begin with. Maybe, they argue, the human beings described in the creation narrative aren’t a model for how we were meant to end up in the first place. For this reason, they believe attributes like gender will be displaced when our redemption is complete—kind of like maternity clothes. Although useful for a time, eventually they become unnecessary.

There is much to appreciate in this view, especially in the connection it makes between gender and the gospel. Nevertheless, it strikes me as self-defeating to tell someone who has experienced pain, difficulty, or any other kind of burden on account of their gender that their hope lies in its removal. Gender seems too vital an element of our life stories for it to be healed merely by erasure. What’s more, if we believe Jesus sets our expectations for resurrection and if he was raised with his gender, then why wouldn’t we expect to be resurrected in a similar way?

Another strand of the Christian tradition goes back to figures like Irenaeus and Augustine, who argued that we are resurrected with our genders precisely because of the hope for justice found in Christ. Something suspicious was going on when people said there would be no gender in the resurrection, Augustine said, when what they really meant was that everyone would be resurrected as a man by default and in exact imitation of Christ.

As Augustine put it, “both sexes will rise again,” for “all faults will be removed from those bodies, but their nature will be preserved.” Since the “female sex is not a sin” nor a defect of creation, women will be resurrected as women. For “the woman … is just as much God’s creation as is the man.” Rather, to be a woman is a glorious gift of the Creator as a bearer of the divine image—just as it is to be a man. God makes all things right by curing creation of its sin, and not by doing away with creation itself.

Therefore, a theology of resurrection that removes all gendered aspects of creation is a theology of erasure that leaves our laments for gendered suffering and injustice—such as dysphoria and discrimination—unaddressed. The resurrection is not a cosmic Etch A Sketch, where God shakes everything to start over; it is a divine commitment to what has already been made and declared very good (Gen. 1:31), which includes our genders.

Irenaeus and Augustine envision the resurrection in terms of a garden. In the beginning, God’s creation was like a seed planted in the earth, intended to blossom into a magnificent tree (Luke 13:18–19). Instead, the tree grew sick with sin. But rather than taking an axe to it, God meticulously cures the tree at the root, and at God’s own expense. Then, and only then, does the tree begin to bloom again.

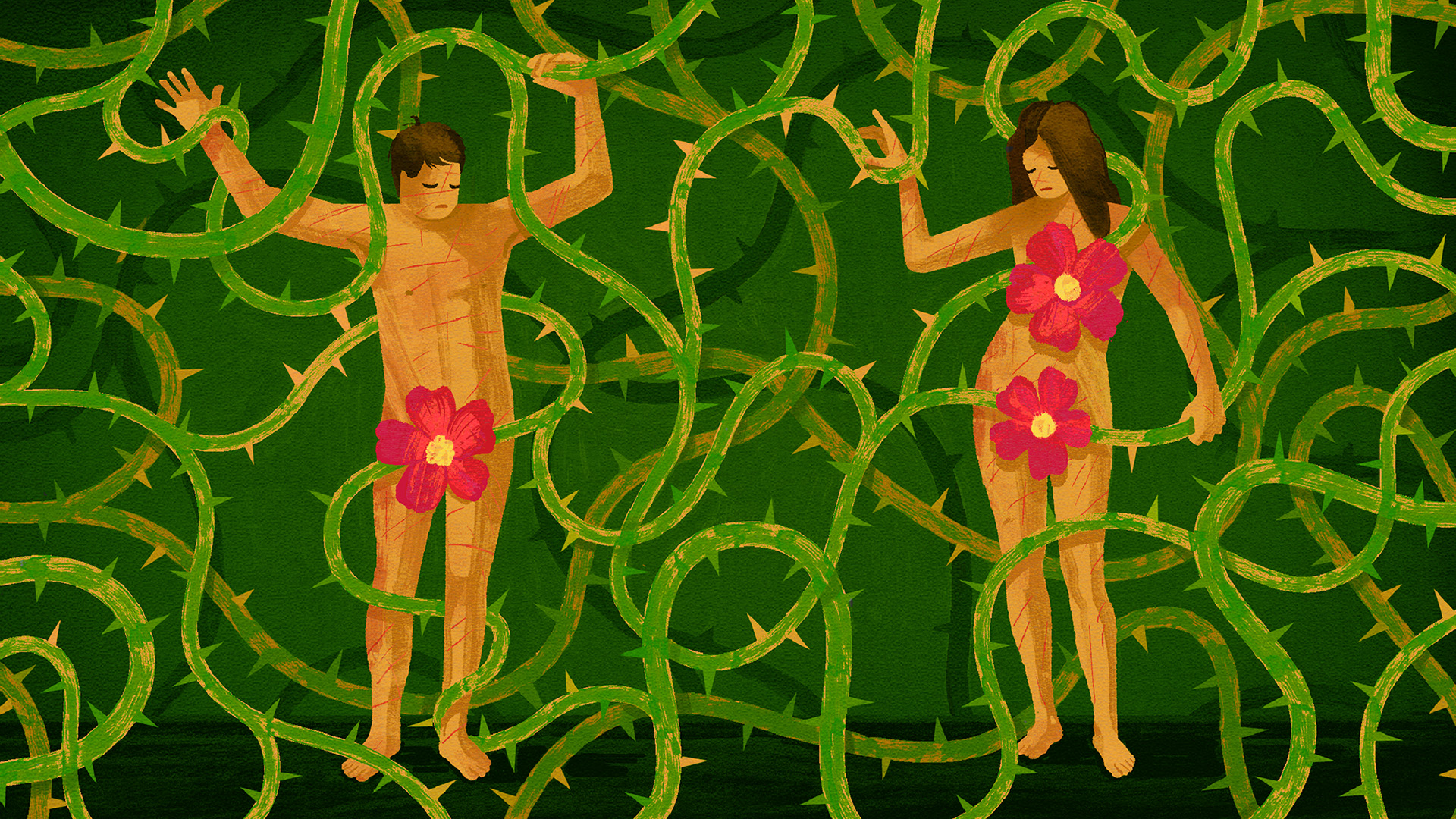

Today, gender is a source of suffering and confusion for many—both our experience and our notions of gender are sick with sin. All around us, we see the ways sexism, abuse, and other forms of harm have hurt God’s creatures, especially women. The virtues that are needed to be a Christlike presence—such as listening well, showing tenderhearted compassion, and not jumping to simplistic conclusions when people share stories about their experiences of gender—are sorely lacking in Christians of all ideological persuasions.

Together, as the body of Christ, we can begin to picture a life where undue and unbiblical burdens associated with gender are alleviated. How can those in the church come alongside each other—our imaginations alight with faith, love, and hope—and envision a world where the work of Christ illuminates our gendered lives? This work begins by recovering the virtues mentioned above: listening well to peoples’ stories, showing compassion to those who hurt, and remaining convinced that there will be no more gendered pain in the kingdom of God. What would our Christian communities look like if we held these virtues in common as expressions of love?

Ultimately, I believe we will remain gendered in the eschaton because of the Christian hope for abundant life and justice. This hope persists because of a conviction that Jesus loves those who are most vulnerable, including those for whom gender is a point of pain.

And while I cannot say with certainty what sex or gender my intersex friend will be raised as, I know her body will be the body God has been helping her cultivate friendship with now. A surprising switch at the end of all things would seem quite out of character with God’s redemptive action.

God is not done with us, nor is God done with our genders. Even now, God is curing us of our sin and giving us a foretaste of what it will feel like to flourish as resurrected women and men.

Fellipe do Vale is assistant professor of biblical and systematic theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and author of Gender As Love: A Theological Account of Human Identity, Embodied Desire, and Our Social Worlds.