Jesus was born in Asia. He was Asian. Yet the preponderance of Christian art that shows him at home in Europe has meant that he is embedded deeply in the popular imagination as Western.

The artists in this photo essay bring him back to Asia—but not to ancient Israel. They make the birth a local event, translating the story into their own cultural contexts. And so we see Jesus wearing, for example, the bone necklace of an Igorot chief (the Indigenous people of northern Luzon, Philippines) or greeted by water buffalo at a roadside pavilion in Thailand.

Some may object to depicting Jesus as anything other than a brown male born into a Jewish family in Bethlehem of Judea in the first century, believing that doing so undermines his historicity. But Christian artists who tackle the subject of the Incarnation are often aiming not at historical realism but at theological meaning.

By representing Jesus as Japanese, Indonesian, or Indian, they convey a sense of God’s immanence, his “with-us–ness,” for their own communities—and for everyone else, the universality of Christ’s birth.

However, it should be noted that not all Asians prefer Asian-specific representations of Christ. In fact, Christians in Asia tend to prefer the traditional European-style art with which many were introduced to the faith; they consider it the most authentically Christian. Part of this preference has to do with how closely tied certain Asian art styles and forms are to other religions, which most Christian converts want to distance themselves from.

That means that the Asian Christian artist who feels called to depict biblical themes, and to do so in an indigenized way, often does not find widespread support in their own country. Perhaps counterintuitively, the largest demand for such art is in the West.

But Christians aren’t the only source of Asian Nativity imagery. Muslims produced many fine examples in the medieval and early modern periods—whether for economic reasons, as an outworking of their own faith tradition’s reverence for Jesus, or simply out of curiosity and attraction. And in the 20th century, Hindu and Buddhist artists were also significant contributors. Whatever the motive or religious background of the artist, visual interpretations of this sacred story offer a gift of beauty to the global church.

Coupled with Asian Christian artists of the past 50 years, vibrant new imaginings of the Nativity abound. These nine artworks proclaim the expansiveness of Christ’s kingdom.

Iraq or Syria: Freer Canteen Nativity

Syria or Northern Iraq, Ayyubid period, mid-13th century. Brass, silver inlay, 45.2 x 36.7 cm (17 13/16 x 14 7/16 in). Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. "This large, impressive canteen, the only known example of its kind from the Islamic world, recalls the shape of ceramic pilgrim flasks. Its inlaid silver decoration combines calligraphy and decorative motifs, such as intricate geometric designs, and lively animal scrolls, with Christian imagery. These include a representation of the Virgin and Child in the center, surrounded by narrative scenes from the life of Christ as well as saints and knights. It has been suggested that the canteen may have been commissioned by a wealthy Christian, perhaps, as a special memento of his travels." https://asia.si.edu/object/F1941.10/

Syria or Northern Iraq, Ayyubid period, mid-13th century. Brass, silver inlay, 45.2 x 36.7 cm (17 13/16 x 14 7/16 in). Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. "This large, impressive canteen, the only known example of its kind from the Islamic world, recalls the shape of ceramic pilgrim flasks. Its inlaid silver decoration combines calligraphy and decorative motifs, such as intricate geometric designs, and lively animal scrolls, with Christian imagery. These include a representation of the Virgin and Child in the center, surrounded by narrative scenes from the life of Christ as well as saints and knights. It has been suggested that the canteen may have been commissioned by a wealthy Christian, perhaps, as a special memento of his travels." https://asia.si.edu/object/F1941.10/From the Islamic Middle East of the 13th century comes an inlaid metalwork image of the Nativity, on the front face of an extraordinary object known as the Freer Canteen (named after the Washington, DC, museum collection it’s in). The canteen was likely made for a Christian layperson in northern Iraq or Syria, and though its form resembles a pilgrim flask, it is too large to have been portable. The identity of the artist is not known.

Appearing under the spout, the Nativity is one of three scenes from the life of Christ surrounding a central image of the Virgin and child, the other two being the presentation in the temple and the entry into Jerusalem. These are meant to be read counterclockwise, just like the Arabic inscriptions that form a band above and below them, wishing the canteen’s owner health and prosperity.

The representation of the Nativity shows Mary reclining over the crib where her son lies, and below, the Christ child appears again, being washed by two midwives. Joseph sits at the right on a stool. What is unique about this scene is that one of the Magi in the upper left wears a sharbush, the furry, triangular headgear of a Mamluk emir from Cairo!

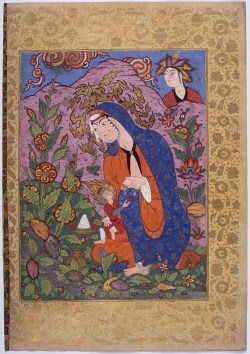

Persia (Iran) or the Ottoman Empire (Turkey): Nativity in the Desert

The Qur’an has its own account of the birth of Jesus, whom Muslims revere as a prophet but not as the Son of God. According to Surah 19:22–26, Maryam (Mary) gave birth to Isa (Jesus) alone in the desert under a palm tree.

This miniature shows Mary breastfeeding her newborn in a remote landscape teeming with color and life. The blue she wears is a convention established in Europe, but her garb is otherwise thoroughly Persianate. So is her posture—crouching on the ground with one knee up—as well as her facial features and the overall style of the composition. Unlike the disk-like halos of European Christian art, the halos of Islamic art are rendered as dynamic golden flames.

The anonymous artist has captured an intimate moment between mother and son, as an angel peeks at them over the purple hills. While Mary offers Jesus her breast milk for food, Jesus offers her a pomegranate—one of the fruits of heaven according to the Qur’an.

The image is from an early seventeenth-century Falnama (Book of Omens) originally owned by Sultan Ahmed I, a compilation of tales of prophets, saints, and rulers that would have been consulted for moral guidance and to explore the unknown.

India: Mughal Nativity

For other similar paintings, see "Biblical Themes in Mughal Painting," plates 47-48. Is it a rose water sprinkler (https://www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org/art/explore-the-collection?id=20641447) in the background? "The custom of sprinkling guests with cool, scented rosewater originated in Iran. As vessels like this one demonstrate, the practice was adopted by elites at Hindu and Muslim courts and, later, by wealthy Europeans in India. | Rosewater was traditionally sprinkled on guests in India because it has cooling and refreshing properties. The tradition of using rosewater came to Mughal India from Iran, where, in the festival of Ab Pashan, rosewater was sprinkled to invoke the memory of rainfall, which would put an end to famine. The custom was gradually incorporated into the Rajput court, where it was used in both ceremonial as well as religious festivals. It is now used in India to welcome arriving guests." (https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/27294). https://www.flickr.com/photos/fn-goa/4496127127/in/album-72157623784396754/. Tags: Indian, India

For other similar paintings, see "Biblical Themes in Mughal Painting," plates 47-48. Is it a rose water sprinkler (https://www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org/art/explore-the-collection?id=20641447) in the background? "The custom of sprinkling guests with cool, scented rosewater originated in Iran. As vessels like this one demonstrate, the practice was adopted by elites at Hindu and Muslim courts and, later, by wealthy Europeans in India. | Rosewater was traditionally sprinkled on guests in India because it has cooling and refreshing properties. The tradition of using rosewater came to Mughal India from Iran, where, in the festival of Ab Pashan, rosewater was sprinkled to invoke the memory of rainfall, which would put an end to famine. The custom was gradually incorporated into the Rajput court, where it was used in both ceremonial as well as religious festivals. It is now used in India to welcome arriving guests." (https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/27294). https://www.flickr.com/photos/fn-goa/4496127127/in/album-72157623784396754/. Tags: Indian, IndiaThis painting is from the era of Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) of the Mughal dynasty, a Muslim Persianate dynasty of Turco-Mongol origin that ruled much of the Indian subcontinent from the 16th to 18th centuries. Like his father, Akbar, Jahangir was interested in Christian art and dialogue. He invited Jesuits into his court and instructed his artists to paint Christian themes after the European prints the Jesuits shared. This one is adapted from a Flemish engraving by Aegidius Sadeler II.

Mary sits with her naked son on her lap inside a refined Mughal interior, wearing a brocaded dress, multiple rings on her fingers, and a tilaka mark on her forehead. The identity of the three figures other than the at the center is indeterminate (unlike in the engraving). They may be visitors seeking to pay homage, attendants, relatives, or some mix thereof. The elderly woman with the headscarf and grapes, whom Jesus looks at curiously, may be a midwife or nurse. The flower-bearing person at the back may be an angel.

China: The Nativity by Luke Hua Xiaoxian

In 1930, Catholic bishop Celso Costantini, the first apostolic delegate to China, established an art department at the new Catholic University of Peking (Beiping Furen Daxue). Its professors and students produced a beautiful crop of Chinese Christian watercolors on silk over the next two decades, until the Chinese government forcibly closed the university in 1952.

One preeminent example of an indigenized Nativity from Furen is by Luke Hua Xiaoxian. Situated at the mouth of a cave in a snowy, mountainous landscape, Mary and Joseph care for the infant Jesus while an angel kneels before him in adoration. Standing above them atop wisps of cloud are seven angels, portrayed in the style of Daoist (Taoist) immortal maidens, playing traditional Chinese instruments, including a pipa (lute), guqin (seven-stringed zither), and qinqin (banjo). Mounted as a hanging scroll, the painting has a starkly vertical orientation that is typical of classical Chinese art.

Korea: The Birth of Jesus Christ by Kim Ki-chang

Kim Ki-chang (김기창 金基昶) (Korean, 1913-2001), "The Birth of Jesus Christ," 1952-53. Ink and color on silk, 76 x 63 cm. https://news.zum.com/articles/85807891

Kim Ki-chang (김기창 金基昶) (Korean, 1913-2001), "The Birth of Jesus Christ," 1952-53. Ink and color on silk, 76 x 63 cm. https://news.zum.com/articles/85807891Born in Seoul to a Christian family, Kim Ki-chang (1914–2001), also known by the artist name Unbo (or Woonbo), came to fame with his traditional ink and brush paintings. During the Korean War, while he was taking refuge at his mother-in-law’s house in Gunsan, he had a series of visions that led him to execute 30 paintings on the life of Christ in this medium.

The scenes are set in Joseon-era Korea, which lasted from 1392 to 1910. In The Birth of Jesus Christ, Mary wears a hanbok—traditional Korean dress—while Joseph wears a wide-brimmed horsehair hat called a gat.

In addition to this reimagined ethnic context, Kim’s painting is unique in its heavy inclusion of women, who bring food for the new parents and blankets for the baby. It’s rare to find such a strong female presence at Jesus’ birth, as most Nativities, drawing on the Gospel accounts, feature wise men and the shepherds (whom artists have assumed to be male) as the main guests.

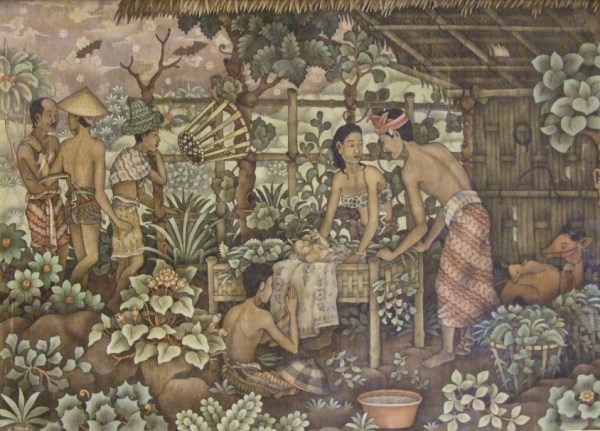

Indonesia: In Bethlehem by I Wayan Turun

Though titled In Bethlehem, the place depicted in this painting is decidedly not that ancient Near Eastern village! Balinese artist I Wayan Turun (1935–1986) relocates the event to the jungles of Ubud, where the infant Christ is laid down for a nap under a bamboo lean-to. Joseph wears a kamen (sarong) with a selendang (belt) and an udeng (headcloth), while Mary wears a kemben (chest wrap). Four agricultural laborers, wearing hats of woven straw or coconut leaves, have come to see the baby, and the animal witnesses include bats, a monkey, and cattle—taking a break from plowing the rice fields.

While Turun was Hindu, he was happy to oblige Western patrons who requested biblical scenes—like the Rev. Henk Visch and his wife, the Rev. Cor Tonsbeek, who worked for the Christian Church of Bali in the 1950s and 1960s and commissioned this painting from him.

Thailand: The Nativity by Sawai Chinnawong

Raised in a Theravada Buddhist household in rural Thailand, Sawai Chinnawong (b. 1959) is an ethnic Mon whose ancestors migrated from Myanmar. His childhood fascination with the local Buddhist temple murals eventually led him to art school in Bangkok, where he was drawn to a nearby Church of Christ community and became a Christian at age 23.

The pastor who baptized him told him his art was too Buddhist and that he had to forsake it. He did—until the next year, in seminary, when he received affirmation from Sri Lankan Christian artist Nalini Jayasuriya that Asian artistic modes can still be compatible with Christian belief. From then on, he has committed himself to painting the gospel in a Thai idiom.

“I believe Jesus Christ is present in every culture, and I have chosen to celebrate his presence in our lives through Thai traditional cultural forms,” Chinnawong said. “My belief is that Jesus did not choose just one people to hear his Word but chose to make his home in every human heart. And just as his Word may be spoken in every language, so the visual message can be shared in the beauty of the many styles of artistry around the world.”

Chinnawong’s 2004 Nativity shows the holy family camped out under a village sala, an open pavilion found on Thai roadsides for strangers to rest or spend the night. Men, women, and children ride in on water buffalo, a traditional form of transportation, to greet the babe. The children sport traditional Thai hairstyles—shaved heads with a Jook (top knot) or a Klae (two ponytails)—as does Joseph. A zigzag line called a sinthao runs across the top of the scene, demarcating heaven and earth, except a star interpenetrates the two realms, suggesting their union.

Japan: Nativity by Sadao Watanabe

The most prolific Asian artist of the 20th century working on biblical themes was Sadao Watanabe (1913–1996) of Japan, who converted from Buddhism to Christianity at age 17. Originally trained as a textile dyer, he pursued a career in printmaking and used a technique called katazome, which entails cut-paper stenciling and dyeing with a variety of natural mineral and organic pigments.

To help correct the common misconception among Japanese people that Christianity is irreconcilable with their culture, Watanabe sought to retell the entire narrative of Scripture using a Japanese aesthetic. “I owe my life to Christ and the gospel,” he said. “My way of expressing my gratitude is to witness to my faith through the medium of biblical scenes.”

In Watanabe’s 1963 Nativity, a procession of eager visitors winds its way over the undulating hills to the Christ child, whom Mary props up in the manger. A bird perched on a lily pad in a lotus pond inclines its head toward the infant, wanting to get a closer look—mirroring the horse, who does the same. Even the sago palm bends its leaves down, as if it too is worshipping.

The Philippines: Ang Kahulugan ng Pasko (The Meaning of Christmas) by Kristoffer Ardeña

In this aerial-perspective Filipino Nativity by Kristoffer Ardeña (b. 1976), villagers with candles gather round the newborn Christ on a handwoven mat. They stand under a parol, a traditional star-shaped lantern made of bamboo sticks and rice paper, meant to symbolize the star of Bethlehem. Flanking the star are a northern tribesman of Luzon (left) and a street sweeper (right), representing how people came from both far and near.

At the bottom, the tastes and flavors of the street market come to the crib as vendors approach with eggplant and calabaza (squash), fish, and balut (steamed duck eggs). Ardeña substituted these three figures for the Magi who brought gold, frankincense, and myrrh because he wanted to emphasize that Jesus’ birth is for the poor as well, and that simple gifts given in love are just as dear to Jesus as any other, according to his artist’s statement in the December 1996 issue of Image: Christ and Art in Asia.

In the center is the holy family, embraced by the wings of a dove with multicolored feathers. Jesus is wrapped in cloth distinctive to the Igorot tribe of Luzon. He wears a necklace of animal bones, a characteristic ornament of an Igorot chief.

Beneath them, on either side of the fish, are two house lizards. The artist said this is a reference to the folk belief that every evening at six, the lizards come down from the ceiling to kiss the floor in reverence to God. If even the lizards honor Christ, he says, then why don’t we?

Victoria Emily Jones blogs at ArtandTheology.org, curates art for the Daily Prayer Project, and serves as a creative director of the Eliot Society.