This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

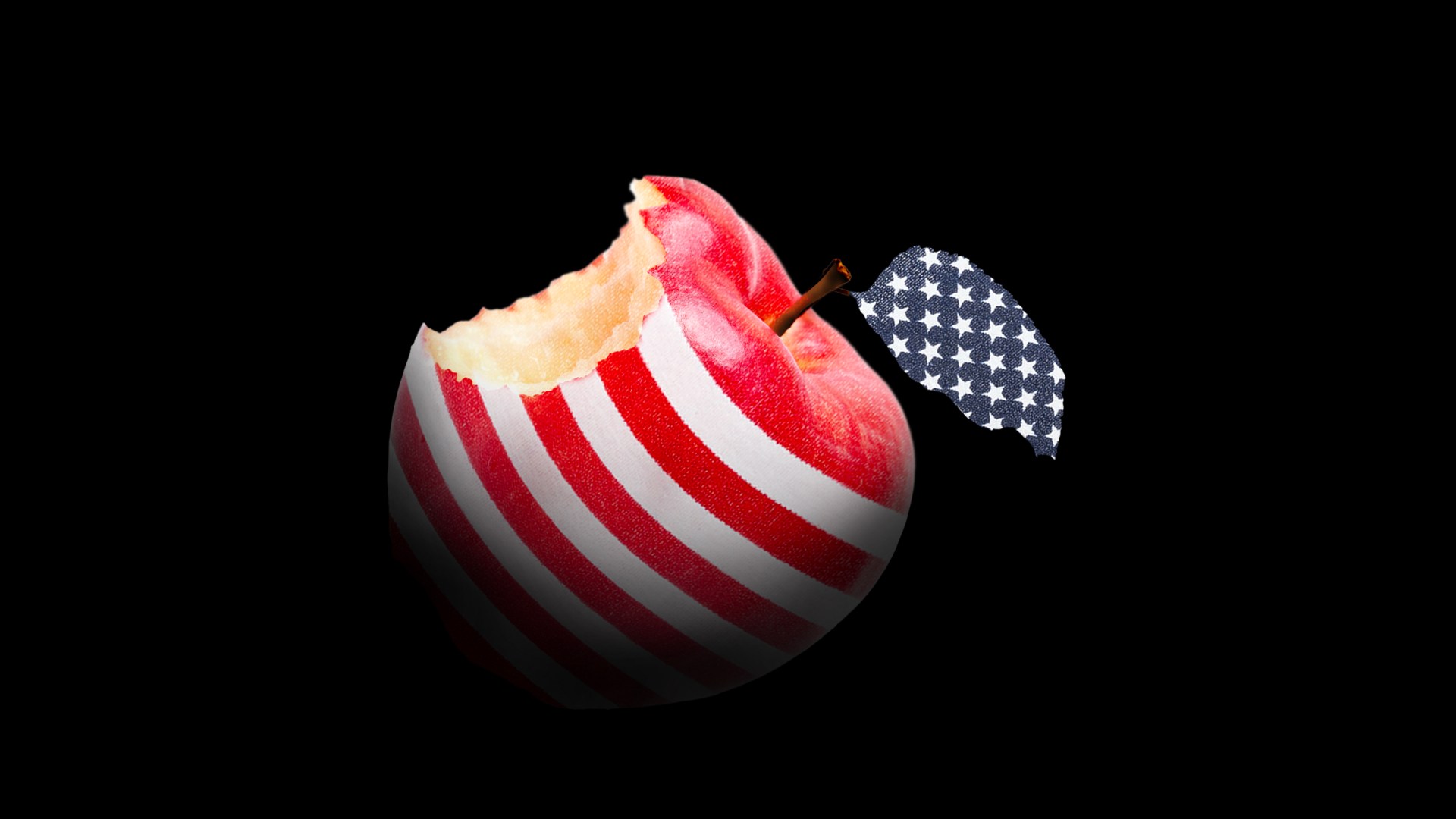

If any political idea in American life has proven itself over the past several years, I can’t think of a better candidate than the “horseshoe theory”—the notion that, at their extremes, Left and Right bend toward each other, sometimes as to be almost indistinguishable.

One of the ways we can see this is in a bleak and darkening view of the United States of America. The question is not so much whether extremists of the Right or Left seem to hate America these days as much as it is the question of why.

Over 15 years ago, then-candidate for president Barack Obama’s campaign was rocked by a videotape of sermons from Obama’s pastor, Chicago preacher Jeremiah Wright, in which Wright spoke of the September 11 attacks in language reminiscent of that of Malcolm X after the John F. Kennedy assassination, as “chickens coming home to roost.”

Wright denounced the idea of “God bless America,” replacing it with instead a call of “God damn America.” The controversy proved to have no staying power—not because most Americans would agree with Wright but because almost no one really believed that Obama himself held to such views. In fact, Obama repudiated his pastor and left the church.

Wright’s bleak view of America was not unusual for a specific strand of the further reaches of the American Left, at least since the Vietnam era. Counter-culture protesters, after all, once burned American flags and referred to the country as “Amerika,” equating the United States with an imperialist dictatorship.

In more recent years, some initiatives such as the 1619 Project have gone beyond the well-established truth that slavery and systemic racial injustice were the original sin and ongoing struggle of the United States. They argue that slavery is, in fact, what the founding was actually about in the first place—therefore making American racism unaccountable to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and rendering it irredeemable.

If this is a “culture war,” then one would expect the Right to defend such traditional values as patriotism of the “America: Love It or Leave It” variety. And yet, we see, if anything, an even bleaker view of America from the more radicalized sectors of the populist Right.

Damon Linker detailed the dark worldview articulated by the “illiberal” intellectuals of the Right, prompting New York Times columnist Paul Krugman to ask, “Why Does the Right Hate America?” The concept of a “Flight 93” view of an American project that should have its cockpit charged and plummeted to the earth is indeed quite a bit of a change from “It’s Morning Again in America.”

Indeed, the sort of Christian language of the United States as slouching toward Gomorrah or as a new Babylon sounds more fitting for a leftist critique of American “imperialism” than for those who once heralded a kind of civil religion that seemed to confuse, if not merge, piety with Americanism.

I found myself asking not long ago, “How did the ‘God and country’ Christians become so unpatriotic? Why do so many self-proclaimed ‘Christian nationalists’ seem to hate their own nation? Why do many progressives seem dismissive of any progress?”

This actually should not perplex us. Psychologists have a category for disordered personalities that idealize and then discard. The person whose spouse is expected to meet all spiritual, emotional, and physical needs—to be the perfect “soulmate”—is usually headed for divorce. The parents who build their entire lives around their children’s accomplishments usually end up estranged from them, or even hating them. We cannot love that which is important but not ultimate if we expect it to be ultimate.

That’s what idolatry always does. We expect our idols to fulfill meanings and purposes they never can. When they disappoint us, we tend to reject and rage against them before seeking some other idol where we repeat the process.

A progressive with a view of an upwardly moving and utopian future will ultimately resent anything short of utopia—even if it is an engine so uniquely conducive to justice and human flourishing as liberal democracy. And a conservative with an idealized view of a golden age of the past will soon come to resent an era that doesn’t live up to the illusion.

The Messiahs who don’t live up to our expectations of them are quickly tossed aside for the Barabbases whom we believe will.

The American founders were not the Christian models that some forms of Christian propaganda (otherwise known as “lies”) have told us. These same founders were not the cartoon supervillains that other forms of propaganda would characterize them to be either. They were sinners who aspired to something they never lived up to—and that we don’t live up to either. The genius was that they didn’t seek to wipe away those tensions.

E. B. White—author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little—taught an entire generation of Americans grammar and the craft of writing. Many of us had our high-school term papers marked up for deviating from the Strunk and White Elements of Style.

In 1936 White argued that not only was the United States Constitution not a sacred document but that it isn’t even a grammatical one. White noted that “We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union” is language meant to turn “many a grammarian’s stomach, perfection being a state which does not admit of degree.” Something is either perfect or imperfect. It can’t be “more perfect” or “less perfect.”

In this one case, though, White was willing to sacrifice the rules. “A meticulous draughtsman would have written simply ‘in order to form a perfect union’—a thing our forefathers didn’t dare predict, even for the sake of grammar.”

A Christian view of humanity should free us to differentiate between a claim to perfection and an aspiration to that which is “more perfect.”

Every era is shot through with grace, and every era since Eden falls short of the glory of God. We can love our parents or our children or our spouses not in spite of the fact that they are flawed but precisely because they are not intended to be our gods.

We can, those of us who are Americans, love America—with all of its flaws and failures—precisely because we don’t expect it to be the kingdom of God.

Christian nationalism can never end in patriotism because it confuses the ultimate and the proximate. Progressive utopianism can never result in patriotism because it does the same.

Genuinely kingdom-first Christianity, though, can and should free us from nationalism, nativism, and perfectionism to truly love God and country, because we know the difference between the two.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.