If one pictures “radical Islam,” chances are the image resembles Osama bin Laden, Boko Haram in Nigeria, or the ISIS fighters of Iraq and Syria. And the connotation is that they are out to kill—or at least to turn the world into an Islamic caliphate.

They are known as Salafis: Muslims who bypass accrued tradition to imitate meticulously the example of Muhammad, his companions, and the first generation to follow them. After the death of the prophet in 632 A.D., the nascent faith’s collective zeal established a sharia-based global empire that did not end until the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Muslims who look like these jihadist images are found in every major American community.

Matthew Taylor counterintuitively argues that, at least in the United States, Salafis actually compare better with evangelicals—the religious group with the most unfavorable perception of Muslims in general.

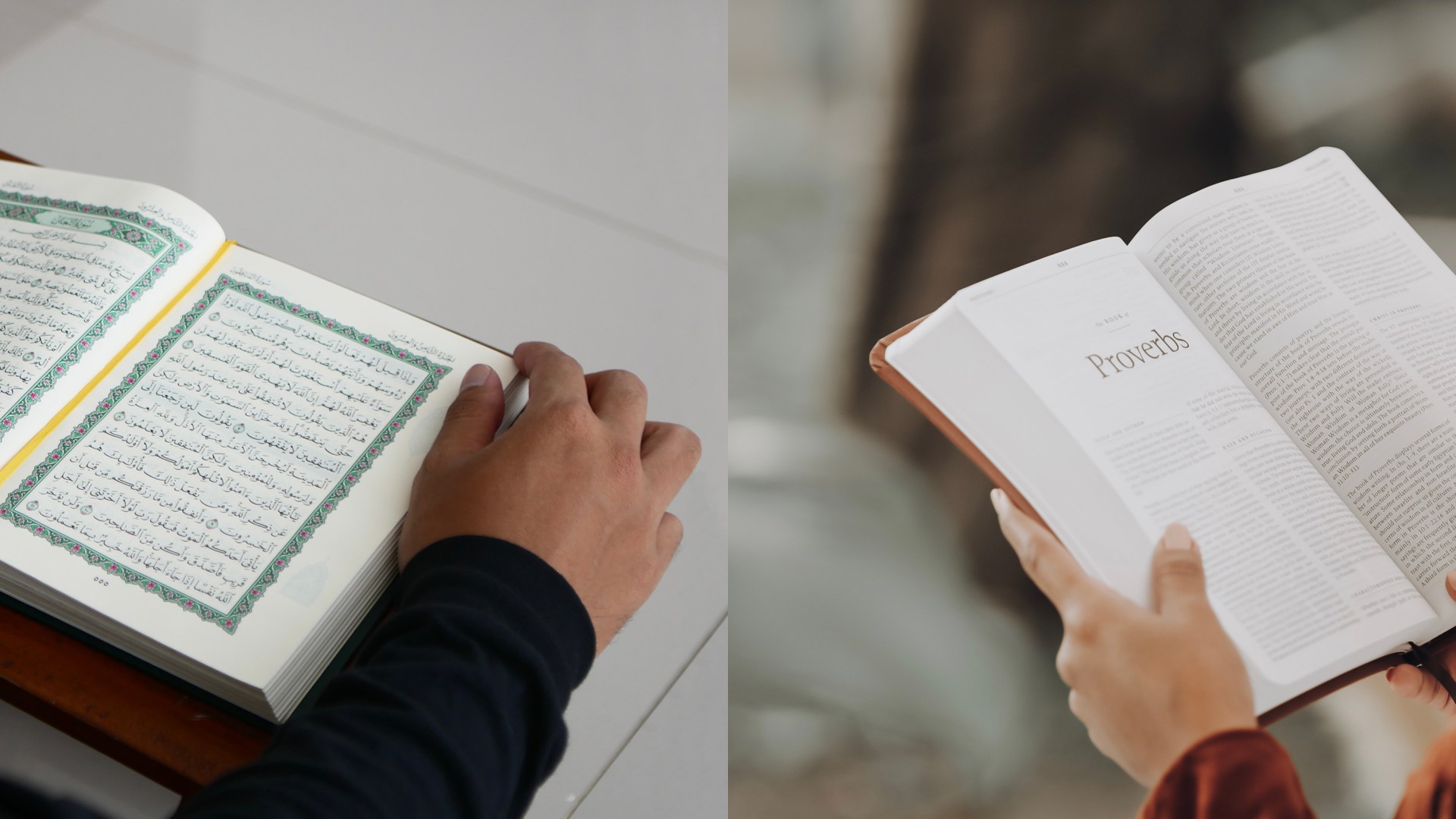

Author of the forthcoming Scripture People: Salafi Muslims in Evangelical Christians’ America, Taylor argues that the Salafi impulse to return to the origins of Islam parallels the evangelical desire to imitate the early church. And both communities, as the title implies, center their approach on sacred text.

The question is: Do the two scriptures take them in radically different directions?

CT asked the Fuller Seminary graduate, now a mainline Protestant scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian, and Jewish Studies in Baltimore, to address the common concern about Salafi extremism and to advise evangelicals on how to pursue a path of possible friendship:

What makes a Muslim a Salafi?

Salafism has very deep roots in the Muslim tradition, and the term Salaf refers to the first generations of Muslims. The idea is to get back to the original authentic practices and theology of Islam, before the tradition became corrupted or diluted.

The Salafi approach involves a direct approach to texts, a deep interest in the Hadith—a secondary scripture in Islam that includes the sayings and actions of Muhammad and the early Muslim community—and a downplaying of the traditional schools of jurisprudence. This is why many Salafis will analogize and call themselves “the Protestant Reformers of Islam.” They see their project as similar to what Martin Luther and John Calvin did in the 16th century.

Can you tell a Salafi simply by their appearance?

It is easier in non-US contexts. A beard is a strong signal that a man is an observant Muslim. And you’ll find Salafi discourse—based on specific hadiths—as very focused around the length of the beard as more than can be grasped in the hand. Traditionally, they adopt distinctive modes of clothing such as the thobe, a long, flowing robe with pants that come up just above the ankles.

Salafi women almost always wear the hijab and others the niqab, which covers the face. But after 9-11, the American security state had an intense focus on Salafis which prompted a process in which many integrated into the American Muslim mainstream, downplaying distinctive Salafi attire and even avoiding always expressly calling themselves Salafis.

How do they justify downplaying their distinctives?

Salafis have a sophisticated understanding of the difference between original theology and original culture. They mimic the normative practices and beliefs of the early Islamic community, while recognizing that the early tradition was occurring in a particular context.

The Prophet Muhammad and his community inhabited a situation of predominant polytheism, among multiple monotheisms. This required great flexibility to operate as a new minority religious community.

Salafism is incredibly diverse—just as evangelicalism is incredibly diverse—and it adapts to fit the environment in which it operates. In the United States, in fact, they have become very open to interreligious dialogue and religious pluralism, all of which might sound contradictory if you associate Salafism with rigidity or fundamentalism.

But it reflects the flexibility built into Salafism, rather than being a violation.

How does this apply to the practice of jihad?

It would be a mistake to singularly characterize Salafis by this term. Islam emerged in a context of inter-tribal conflict, often very brutal and violent. The early Islamic tradition reflects substantially on questions of legitimate warfare, when it is acceptable, how it should be conducted ethically—just war theory, so to speak.

As a result, there is a diversity of perspectives within Salafism. Salafi-jihadis such as ISIS and al-Qaeda endorse jihad against their enemies. Political Salafis, who often are in conversation with groups like the Muslim Brotherhood, are invested in politically taking over Muslim-majority societies—sometimes through democracy, sometimes not.

And then there are the purist Salafis, who are not interested in jihad, nor interested in shaping the politics of the Muslim-majority world. They simply want to live piously and scripturally wherever they find themselves, bearing witness to their tradition. This is called da’wa, is similar to evangelism, and is very important to them.

The vast majority of Salafis in the US are in this third, purist strand.

But for the most part, their proselytism efforts are directed towards their fellow Muslims and showing how pure and correct their version of Islam is. That doesn’t mean that they don’t want to see people convert to Islam. They do. But the goal is not the takeover of society.

For most Salafis in the world, jihad is at best a tertiary concept.

In America, most would say that jihadism is bad Salafism. It misunderstands the situation that Muslims are in. It is not that jihad is never permissible, just as most Christians would not say that war is never permissible. In Europe and many parts of the Muslim world, Salafis feel like they are in a battle—either to try to take over society or to keep their distance from the general culture. But they look at America and say: We have freedom here.

Some Salafi teachers I profile in the book would even say that in the US, you can be more Salafi than anywhere else in the world, because you have freedom of religion.

But a key Salafi teaching is that Muslims not living under Islamic law should emigrate to where they can.

This is the concept of hijra, when Muhammad left a situation of persecution in Mecca to begin a Muslim-led community in Medina—the starting date for the Islamic calendar.

Theologically, conventional Salafis say this is the moment when the prophet gained his civic role, resulting in protection and the shaping of a Muslim society. It is a precedent that Muslims should imitate today—often interpreted as living in a Muslim land, or at least their own insular communities. And in the 1990s, this was a big topic of conversation in the Salafi community in the US.

But today, many American Salafis point out that Muhammad was not antagonistic to the pagan or Christian Meccans, and as long as he and his community existed in peace, they felt comfortable being there. And this becomes the model instead.

It is a direct refutation of this imperative of hijra, though living conservatively still requires community, attending mosque, and training in scripture. But there is no hostility to the broader culture.

But hostility is also a deep part of the tradition, that Muslims should not be friends with non-Muslims.

This is the concept of wala’ wa bara’—loyalty to your friends, and enmity to the enemies of God. Yes, that’s a Salafi idea or principle, but how do you apply it? Traditionally it means there must be no alliance or partnership that relies upon those who neglect or oppose the principles of Islam.

But most American Salafis say that since the culture is neutral towards us, only people who are overtly Islamophobic—who want to get rid of Muslims—are our enemies. Since most Americans are not that way, since most Christians are not that way, we don’t need to choose a default hostility. We just need to be thoughtful about cultivating friendships, as any evangelical would do.

How does their hermeneutic allow for such changes?

Generally speaking, it is through a commonsense appeal directly to the text of the Quran and Hadith. But just as with evangelicals, the methodological articulation of that hermeneutic can be rather thin.

They certainly do not rely upon centuries of legal reasoning, as would most traditional Muslims. The argument that contemporary American Salafi scholars are making is that they have been trained in hermeneutics and they live in this culture, so why should they look to other cultures, such as Saudi Arabia, for cues on how to live here?

I would argue their reasoning, while going back to scripture, is less about parsing the fine points between the experience of early Muslims in Mecca or Medina and more of a pragmatic presentation that argues this different, American way of being Salafi is also authentic.

How does this compare with traditional Islam?

The relationship between traditional and Salafi Islam is mirrored in the mainline Protestant and evangelical divide. I contrast the educational institutions that Salafis have built in America, like AlMaghrib Institute, with more traditional Islamic educational institutions like Zaytuna College.

Zaytuna follows more of a madrasa form of Muslim education, translating it into the American liberal arts model. They teach the various traditions of jurisprudence, concerned about raising up the next generation of formal religious leaders. It is a vanguard model of education: training scholars and leaders in the tradition who can then interpret the tradition for everyone else.

The Salafi ethos resembles evangelicals in the spirit of empowering ordinary people not only to study scripture but to equip them with tools to teach others. AlMaghrib Institute has taken more of a parachurch—or paramosque—approach to education.

It reminds me of when I was a student leader with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. I’m studying the Bible, and I’m teaching the Bible, but I’m not at all accredited by an institution. Evangelicalism and Salafism both have the egalitarian sensibility that scripture is not sectioned off as the realm of the elite.

What’s fascinating to me is that America has always been a laboratory of religious pluralism, where you have, originally, all these different forms of Protestantism—and then Judaism and Catholicism and other religions—that are learning to work without state establishment.

So it is not shocking to me that Salafism would not only flourish in this space, but evolve in ways that make it very distinct not only from traditional Islam but from the traditional forms of Salafism worldwide.

What are three tips for evangelicals to make friends with Salafis?

First, focus on your love for scripture. And then allow them to talk about theirs. Muslims across the board love talking about the impact of the Quran on their lives, and Salafis do so to the nth degree. Both communities treasure the text.

Second, look for surprising places of agreement. Similar to evangelicals, Salafis have anxieties about liberal or progressive tendencies in culture—while looking for spaces of collaboration. They practice their faith by serving the poor, and friendships can be cultivated around social justice and concern for society.

Third, don’t forget the simple dialogue of life. Everyone deals with the same stuff: bills to pay, food on the table, grocery shopping, and after-school activities. Many times, we think we have to center dialogue on the religious questions and make everything a conversation about faith. But that’s not how friendship works; friendship is life, together. The more we engage in small talk, the more trust can be built for more complicated religious conversations.

What do you recommend for sharing the gospel?

The best dialogue, the best conversations, even the best evangelism, begins in an authentic witness to what you love about the religious identity that you hold. And more than with any other community within Islam, evangelicals and Salafis can come together and say: We really love the text. Let’s study the text together.

You can even say you want them to follow Jesus. Just be ready for them to reply that they would like you to become a Muslim.