In 1904, thousands of indigenous people were brought to the St. Louis World’s Fair to be put on public display. Scientists offered them as examples of lower stages of human evolution. Some were even presented to the public as “missing links” between humans and apes.

Two years later, an African named Ota Benga was exhibited in a cage next to an orangutan in the Bronx Zoo primate house. The display attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors. It also drew protests from Black and white clergy. Black minister James Gordon attacked the presentation for propagandizing on behalf of Darwinian evolution, which he regarded as “absolutely opposed to Christianity.”

“Neither the Negro nor the white man is related to the monkey, and such an exhibition only degrades a human being’s manhood,” he declared.

Scientific and cultural elites, meanwhile, saw nothing wrong.

Leading evolutionary biologist Henry Fairfield Osborn of Columbia University praised the zoo exhibit, while The New York Times complained it was “absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation” of Benga. The Times took special umbrage at Gordon’s skepticism of evolution: “The reverend colored brother should be told that evolution, in one form or other, is now taught in the text books of all the schools, and that it is no more debatable than the multiplication table.”

Only recently have many members of the scientific community begun to grapple with evolutionary biology’s disturbing past. Last year, the science journal The American Naturalist published an article acknowledging that “the roots of evolutionary biology are steeped in histories of white supremacism, eugenics, and scientific racism.”

This fraught history helps explain why biologist Joseph L. Graves Jr. reports in his recently published book that he was “the first African American to earn a PhD in evolutionary biology.”

The work is titled A Voice in the Wilderness: A Pioneering Biologist Explains How Evolution Can Help Us Solve Our Biggest Problems (Basic Books). Part autobiography and part polemic, it recounts the author’s powerful personal story of how he overcame the obstacles of racism to pursue a successful career in biology. His various struggles—including the death of his younger brother from AIDS contracted as a hospital doctor—are raw and affecting.

But A Voice isn’t simply about Graves’s backstory. It also addresses the broader social, political, and cultural problems that America faces. The author offers a way to meet these formidable challenges: by leaning into evolutionary theory and its wide-ranging implications.

Given current debates, a fresh take on evolution and its implications is certainly timely. Over the past decade, increasingly sophisticated scientific challenges to Darwin’s theory have proliferated. In 2016, England’s Royal Society—one of the most august scientific bodies in the world—convened evolutionary scientists from around the globe to rethink how evolution works. Why? Because a fair number of biologists are recognizing the inadequacy of the Darwinian mutation-selection mechanism to explain how the major features of life developed.

Alas, Graves doesn’t grapple with these new developments, preferring to present the evolution debate through the trope of Christian fundamentalism versus science. He caves to stereotypes that say only ignorant or religiously motivated people raise questions about evolution.

By doing so, he misses all the current conversations going on in biology and related fields. Science is rife with fresh debates about teleology, design, and purpose. The old dichotomy of evolution versus creation has increasingly given way to competing versions of evolutionary theory and the re-emergence of design-based science.

Graves’s writing is equally unsatisfying in its exploration of social and metaphysical questions raised by Darwin.

To his credit, he acknowledges the role that social Darwinism, eugenics, and racism played in the history of evolutionary biology. One of the best parts of the book is his takedown of scientific racism and his effort to disentangle evolutionary biology from its past. For example, he critiques misguided efforts to tie variations in IQ to race and DNA, pointing out that “evidence supporting a differential genetic foundation for racialized intelligence has never been found.”

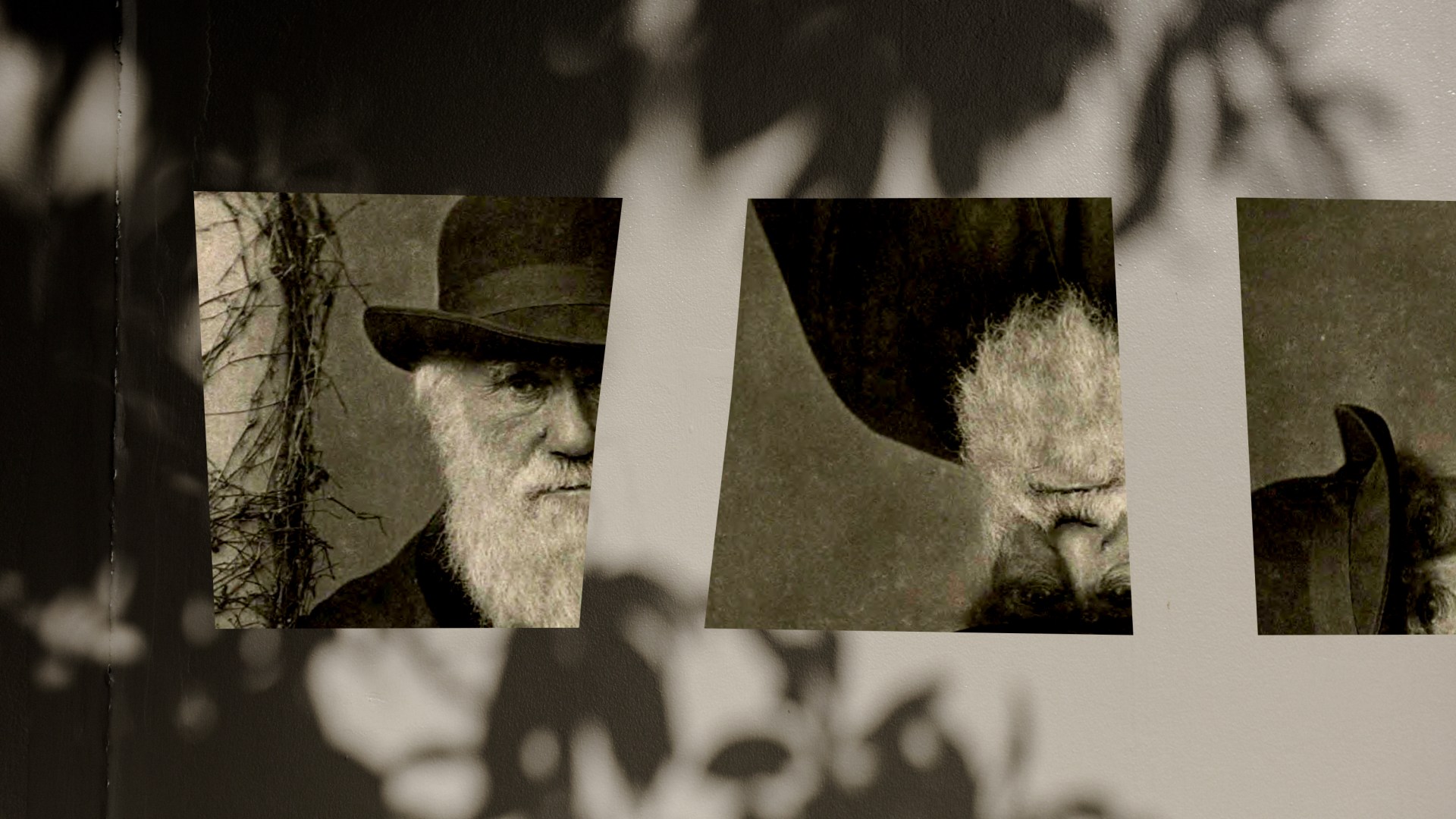

Less successful is Graves’s overly protective effort to airbrush Darwin out of the picture. He’s correct in arguing that Darwin didn’t invent racism and even opposed slavery. Nevertheless, he avoids grappling with how the 19th-century thinker played a pivotal role in the development of scientific racism and related evils like eugenics.

In The Descent of Man, Darwin claimed that the break between humans and apes fell “between the negro or Australian [aborigine] and the gorilla.” In his view, Blacks were the closest humans to apes. He also argued that the differences in mental faculties “between the men of distinct races” were “greater” than the differences in “mental faculties in men of the same race.”

As Nigerian scholar Olufemi Oluniyi has pointed out, Darwin’s writings “clearly demonstrate that by ‘barbarous,’ ‘inferior,’ or ‘lower’ peoples, he usually meant dark-skinned people. The terms ‘highly civilised’ or ‘superior’ he applied to Caucasians.”

Darwin offered a seemingly plausible scientific rationale for racial inferiority. According to him and his supporters, we should expect races to have unequal capacities, because natural selection will evolve different traits for different populations based on their survival needs. These ideas unquestionably helped solidify and spread scientific racism.

As evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould writes in Ontogeny and Phylogeny, “biological arguments for racism may have been common before 1859,” when Darwin published On the Origin of Species, “but they increased by orders of magnitude following the acceptance of evolutionary theory.”

Seeking to absolve Darwin, Graves largely blames the origin of scientific racism on those in history who believed in “special creation.” To do so, he cherry-picks Christians who claimed that God created different races. But he misses the fact that such “polygenist” views contradict orthodox Christian teaching. A plain reading of Genesis 1:27 (“So God created mankind in his own image”) and Acts 17:26 (“From one man he made all the nations”) makes clear that God created one human race, all in his image, and all descended from a single couple (Gen. 3:20).

Far from promoting racism, biblical passages on the special creation of humans give Christians a foundation to argue for the equality of all. They inspired Christian abolitionists like Olaudah Equiano, Albert Barnes, J. D. Paxton, and Theodore Weld.

Two other features of A Voice in the Wilderness may also give some readers pause. The first one concerns Graves’s invective against those who hold views different than his own—political conservatives in particular. For example, he compares Donald Trump with Stalin and Hitler. He attacks “the insane logic of capitalism.” And he too easily labels his opponents as “white supremacist[s]/fascist[s].”

Whatever the merits of Graves’s scientific and political perspective, his language is likely to strain bridges rather than build them.

Second, Graves’s autobiographical story hampers his message. By his account, he became an atheist after reading two authors. One was Karl Marx. The other was Charles Darwin. He says reading Darwin “raised monumental theological questions in my mind concerning the nature of God” and made him “militantly atheistic.” Graves does not regard his experience as exceptional: “I am a member of the community of professional evolutionary scientists, most of whom are … atheist.”

Unlike his colleagues, Graves found a road back to faith of a certain kind. What he embraced post-Darwin was not the Bible-believing faith of his parents. In fact, he came to view Scripture as a fallible document that “evolved naturally across time,” and he embraced old-style higher criticism like the discredited “documentary hypothesis” of the Pentateuch. He also rejected historic biblical teachings about sex and gender. For Graves, this “progressive” Christianity seems to be the only viable form of faith in light of Marx and Darwin.

Altogether, A Voice in the Wilderness serves as a cautionary tale. At times, it movingly portrays the struggles of a Black man facing racist oppression as he pursues his passion for science. This part of the story deserves more attention. At other times, however, Graves’s story is less compelling. He glosses over the negative impact of evolutionary theory on Blacks and other minorities and ignores new developments in biology that raise questions for textbook Darwinism.

On the social and political front, Graves lacks charity toward his opponents. And his personal faith journey is a story of fracture and biblical infidelity. In the end, A Voice in the Wilderness speaks a distinct and memorable message. Unfortunately, it’s unlikely to lift up the valleys or make the rough places smooth.

John G. West is vice president of Discovery Institute and director of the documentary Human Zoos: America’s Forgotten History of Scientific Racism. Eric M. Wallace is a biblical scholar and president of Freedom’s Journal Institute for the Study of Faith and Public Policy (FJI).