Two years ago on this site, I defined Christian nationalism and warned of its dangers. Last year I published my book on the subject. Despite that, there still seems to be a persistent chorus of voices complaining that the term lacks clear definition and is mostly useless.

This becomes a real problem when we’re trying to assess the actual threat Christian nationalism poses in our country. For instance, Religion News Service ran a piece last month announcing the results of a recent Public Religion Research Institute poll, which found that nearly a third of Americans—most of them white evangelicals—were Christian nationalists.

However, former faith coordinator for the Obama administration Michael Wear pointed out on Twitter some flaws with the way this poll was conducted and the conclusions drawn from its results.

This is due, in part, to the fact that the poll questions were worded in a way that was ambiguous at best and misleading at worst. It turns out that some of the respondents included in that “one-third” statistic did not, in fact, understand what the term Christian nationalism even meant.

That poll, as well as the Twitter controversy surrounding it, further highlights the fact that an issue as serious as Christian nationalism demands a clear and unequivocal definition.

Whatever we think of the term Christian nationalism, the thing it refers to is real, and the thing needs a label. The thing I’m trying to label is simple: Americans who believe that America is a “Christian nation” and that the government should keep it that way.

Of course, that does leave a lot to unpack, so it is worth spending some time trying to make it more specific. What exactly does Christian nationalism (or whatever you want to call it) look like in practice? How do we know the difference between (bad) Christian nationalism and (good) Christian political engagement?

Christian nationalism looks like the 45 percent of Americans who believe the United States should be a Christian nation and the 44 percent who believe that “God has granted America a special role in human history.” Christian nationalism looks like the 35 percent of Americans who believe that a citizen should be a Christian to be “truly American.”

Christian nationalism looks like citing Psalm 33:12 (“Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord”) or 2 Chronicles 7:14 (“If my people, who are called by my name…”) in reference to the United States, implying that America is the nation whose God is the Lord, that we are God’s people called by his name—a common practice in white evangelical circles.

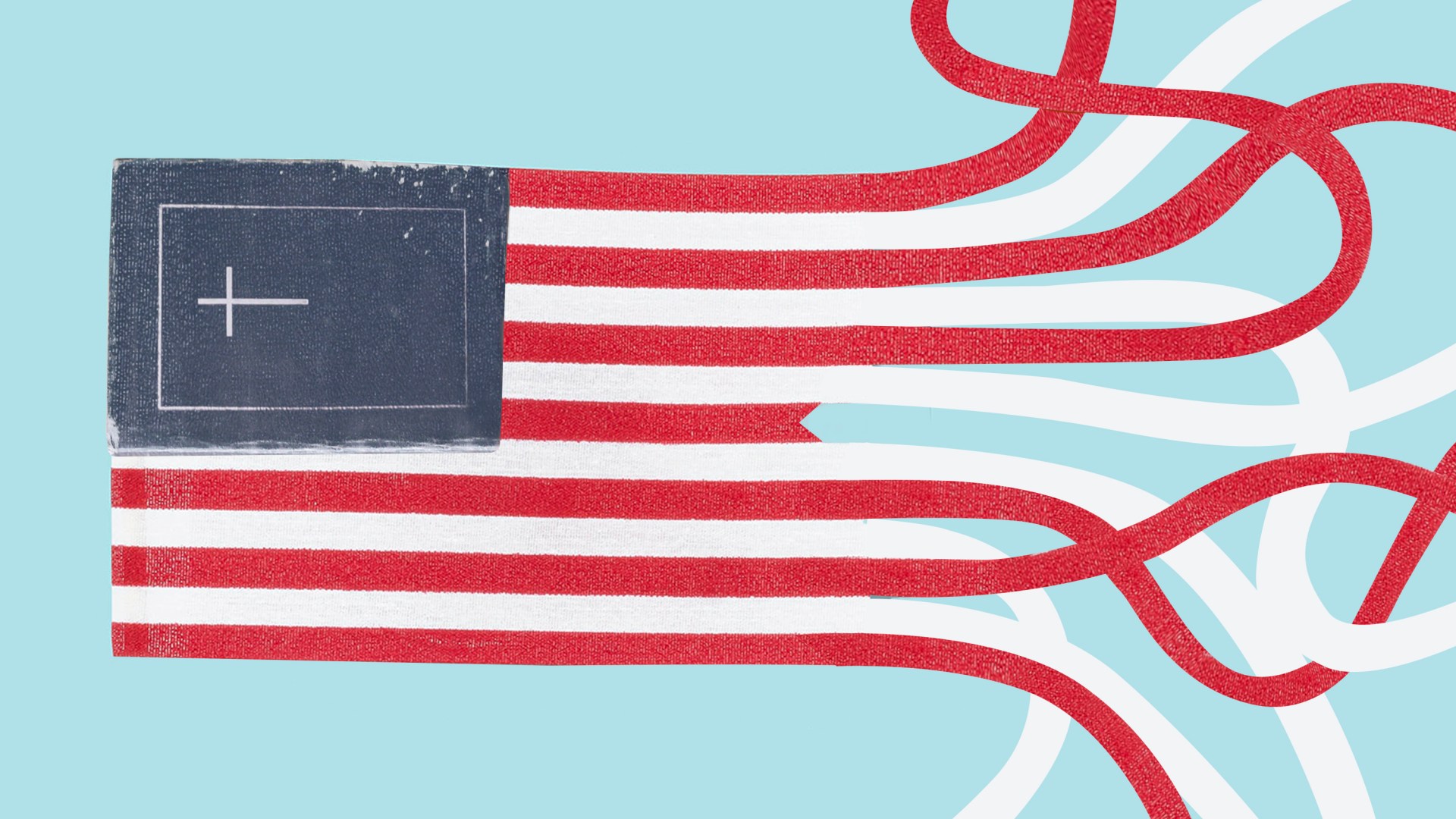

Christian nationalism looks like the American Patriot’s Bible, which “shows how the history of the United States connects the people and events of the Bible to our lives in a modern world. The story of the United States is wonderfully woven into the teachings of the Bible.” Christian nationalism looks like putting the American flag on central display in your local church.

Such images of Christian nationalism show a broadly popular, mainstream, peaceful movement that is wrongheaded, foolish, and both theologically and constitutionally suspect. But they also show that American evangelicals need a better understanding of political theology and American civics.

It is important to add, however, that Christian nationalism can also show up in more sinister guises. For example, Christian nationalism looks like a xenophobic candidate for the US Senate tweeting his opposition to welcoming Afghan refugees because, he argued, they endanger our “Judeo-Christian way of life.”

Christian nationalism looks like the ReAwaken America Tour, in which thousands of Christians packed churches for political rallies to cheer on conspiracy theories about the 2020 election or the COVID-19 pandemic.

And Christian nationalism looks like invoking Jesus’ name and offering a prayer to God on January 6, 2021, thanking him for the opportunity to storm the US Capitol to show “that this is our nation,” for “filling this chamber with patriots … that love Christ” so that “the United States [could] be reborn.”

Christian nationalism is an attitude, a stance toward America and the world—a way of situating ourselves and our nation in a moral and theological framework. In this framework, Christianity and America go hand in hand: They’ve gone together since the founding of our country, and they should continue to stay in sync for as long as faithful American Christians can manage it.

Christian nationalism is a presumption that Christians are America’s first citizens, architects, and guardians and that we have the right to define the nation’s culture and identity. It is a sense of ownership, a proprietary or possessive feeling: Christians invented America and therefore have the right to stay on top.

Christian nationalism can be oddly difficult to translate into specific policy positions. It focuses much more on demanding symbolic recognition for Christianity. “Public life should be rooted in Christianity and its moral vision,” according to the National Conservatism website, “which should be honored by the state and other institutions both public and private.”

Policies driven by Christian nationalist goals focus on things like bringing back teacher-led prayer and Bible study in public schools, restricting immigration only to people who share our values, or mandating the teaching of American history as a Christian nation. It might eventually include an attempt to revise the US Constitution to acknowledge Christianity, as a group of ministers proposed in 1863.

Christian nationalism also advocates for much stronger and more robust morals legislation—which, by itself, can be a good thing, but not if it appeals to a sectarian or discriminatory standard of morality. Christian nationalists tend to overestimate the popularity of their view of morality and the competence of the state to enforce it and to underestimate the dangers of blowback (as with Prohibition).

That said, none of the dangers of Christian nationalism preclude patriotism, Christian involvement in politics, or working for justice in the public square. Being pro-life or pro-religious liberty is not Christian nationalism. Being grateful for America, honoring the founding fathers, recognizing the blessings of the US Constitution (as amended) and Declaration of Independence, and recognizing the positive influence of Christian principles on American life are all good things.

In between, there is a gray area of America’s “civil religion,” the traditions and pageantry of our civic life that often borrow generically religious language and symbolism. Political leaders often invoke God in their addresses, ceremonial occasions begin with prayers, there are crosses on public grounds across America, and many churches celebrate American holidays, like the Fourth of July and Memorial Day.

I tend to think that such instances can, in principle, be harmless but have the potential to become harmful. A lot depends on the specifics and on the heart attitudes of those leading the way. Is public prayer truly intended to honor God or to troll secular progressives? Are crosses on public lands a true and inclusive reflection of American history that can also include other religious symbols, or are they intended as exclusionary symbols of Christian supremacy?

The most important difference between bad Christian nationalism and good Christian political advocacy is in our heart posture. Are we seeking to advance Christian principles or Christian power? Are we seeking equal justice for all or privileges for our tribe? Are we seeking to love our neighbor with our political witness or show our neighbor who’s boss?

Christians are called to seek the welfare of the city in which we are presently exiled (Jer. 29:7). In a nation in which we have the privilege of democratic citizenship, seeking our city’s welfare means loving our neighbors by voting for justice and righteousness. It does not mean securing our tribe’s predominance or ensuring the nation makes our culture central to its identity.

Paul D. Miller is a professor of the practice of international affairs at Georgetown University, a research fellow with the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, and a veteran of the war in Afghanistan. His most recent book is The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism.