I find the Germans have a word that perfectly encapsulates a particular feeling that’s been lingering within me lately. They call this one weltschmerz, while the French refer to it as the mal du siècle. Though foreign to me, these words describe a very familiar feeling: a melancholy ache in the pit of my stomach when I realize the world is not as it should be—that selfishness and greed pervade the nations, that humans are capable of indescribable acts of violence against each other, that the most terrible things can happen without cause or reason.

Today, I sat with a friend whose daughter died last year at just 11 days old. The death of a child is a pain so unbearable that it’s terrifying to look this grief in the eye, even from a distance. That we live in a world where such a thing can happen is a heartache that looms under the surface for many of us. Weltschmerz describes this realization—an epiphany of sorts where we resonate with what philosopher Frederick C. Beiser defines as “a mood of weariness or sadness about life arising from the acute awareness of evil and suffering.”

Perhaps it was a feeling that was easier to ignore before, when rolling cable news banners and social media alerts did not invade our safe spaces. For many of us, the badness feels ever-present now and the shadow of world-weariness is able to grow until it feels suffocating in a way that was not possible before.

Like many other millennials, I have been gripped by an acute sense that the world is getting worse, with disaster around every corner. From climate catastrophes to polarization and political unrest to economic uncertainty, we have been forced to confront our own helplessness.

I am someone who likes to fix things. If I see a problem or witness someone suffering, I can’t help but try to come to the rescue. I have grown addicted to the affirmation that comes with playing the hero. But part of the discomfort of weltschmerz is the realization that I can’t mend the world’s brokenness. I am subject to its precarity, incapable of standing above it. Its wholeness does not lie in my hands.

During this season of Lent that leads up to Easter, I feel we must put to death the idea that we were ever the ones in control. We need to put to death a self-reliance that wrongly suggests we might be able to fix the world rather than relying on God, the only one who is able to make things right. As St. Augustine writes in his Confessions: “But you, Lord, ruler of heaven and earth, turn to your own purposes the deep torrents. You order the turbulent flux of the centuries. Even from the fury of one soul you brought healing to another.”

And yet, despite God’s omnipotence, Jesus wept. The incarnate God in human form stands alongside us as we bear witness to the pain and suffering of this world. Through Lent, we remember Jesus’ arrival at Bethany in the days before his death, where Martha and Mary are in despair, angry at him for having let their brother Lazarus die. Jesus stands with them in their emotional turmoil and makes their pain his own. He weeps with them. And in the garden of Gethsemane, as Jesus begs that the cup of suffering and death be taken from him, he is in such anguish that his sweat falls like drops of blood. Not polite and containable tears but a torment that rises from the depths of his soul. This is a God who weeps—a God who ugly-cries. God is intimately acquainted with the ache of weltschmerz.

How then shall we live in light of the knowledge that the world is not as it should be, that we are not omnipotent, but that God is? Few have said it better than Mr. Rogers: “I'm fairly convinced that the Kingdom of God is for the broken-hearted. You write of 'powerlessness.' Join the club, we are not in control. God is.”

We could be forgiven for responding with apathy in the face of this world-weariness, giving in with a shrug of the shoulders to the understanding that “everything is futile,” as we read in Ecclesiastes. But we know that the wrongness of the world will be made right through the arrival of the kingdom of God. We know that we should not grieve as those who have no hope (1 Thess. 4:13).

Recognizing that we live in the now and the not yet of the kingdom of God, we cling to the eschatological hope that all will be made new. After Jesus’s crucifixion comes his resurrection. The light breaks into the darkness. The veil of suffering, darkness, and despair is torn in two.

As we put to death our self-sufficiency and self-reliance when it comes to the idea that we alone can fix the brokenness of this world, surrendering to something—or someone— greater, we reject the futile apathy of the hopeless. Jesus in the Garden still prays in the middle of his pain and anguish. Jesus does not give up on relationship.

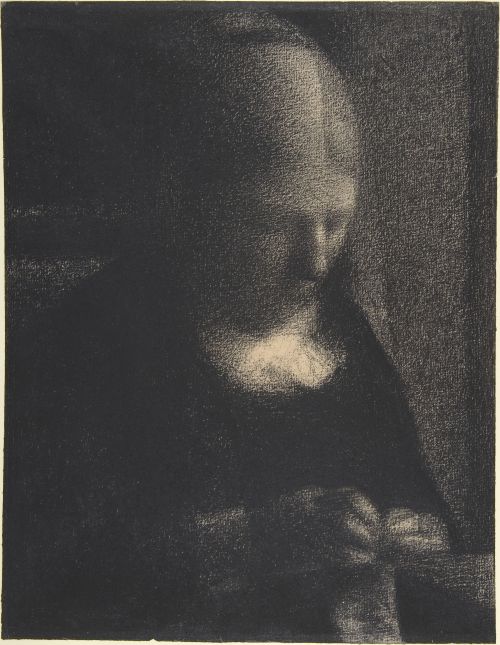

George Seurat / Wikimedia Commons](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/secure.notion-static.com/9c381fe2-9143-41b3-9a96-e694496306db/The_Artists_Mother_188283_Georges_Seurat_.jpeg) The Artist’s Mother by George Seurat / Wikimedia Commons

George Seurat / Wikimedia Commons](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/secure.notion-static.com/9c381fe2-9143-41b3-9a96-e694496306db/The_Artists_Mother_188283_Georges_Seurat_.jpeg) The Artist’s Mother by George Seurat / Wikimedia CommonsGod is in control, but we too can play our part. Rather than wallowing in weltschmerz, we can take up God’s invitation to be colaborers in building the kingdom. Instead of being paralyzed into inaction and apathy, we can do something—even the smallest of things—to offer glimmers of wholeness, of shalom.

My friend who experienced the tragic death of her baby daughter last year has chosen to do something rather than resign herself to the existential apathy of unimaginable loss. She and her husband have raised thousands for the hospital where their daughter died that will go towards rooms that other parents can stay in during the first few days of their child being admitted.

This is what hope looks like in the face of world-weariness. Fervent prayers through the anguish in the Garden of Gethsemane. Action instead of apathy, love instead of hate, prayer instead of silence; and ultimately recognizing that despite the familiar ache of weltschmerz that lurks just beneath the surface, we can choose hope instead of despair because of what Christ did on the cross. As Jesus said: “I have told you these things, so that in me you may have peace. In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world” (John 16:33).

Chine McDonald is a writer, broadcaster, and author of God Is Not a White Man: And Other Revelations. She is the director of Theos, the UK’s leading religion and society think tank.

This article is part of New Life Rising which features articles and Bible study sessions reflecting on the meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Learn more about this special issue that can be used during Lent, the Easter season, or any time of year at http://orderct.com/lent.