There’s a downside to going someplace where everyone knows your name.

Author and Bible teacher Beth Moore discovered that reality in the months after making a public break with the Southern Baptist Convention, which had been her spiritual home since childhood.

Whenever she and her husband, Keith, would visit a new church, the results were the same. People were welcoming. But they knew who she was—and would probably prefer if she went elsewhere. Once the very model of the modern evangelical woman, she was now a reminder of the denomination’s controversies surrounding Donald Trump, sexism, racism, and the mistreatment of sexual abuse survivors.

When Moore would no longer remain silent about such things, she became too much trouble to have around. Even in church.

“I was a loaded presence,” she told RNS in a recent interview.

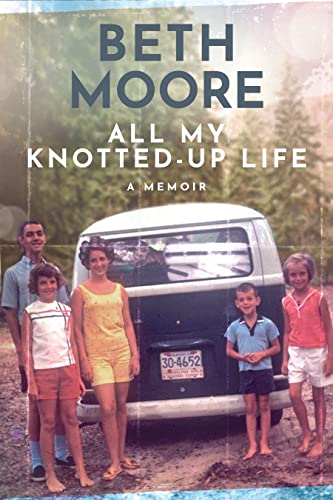

In her memoir, All My Knotted-Up Life, out this week from Tyndale, Moore recounts how the couple ended up at an Anglican church in Houston, largely at the suggestion of Keith Moore, who’d grown up Catholic and felt more at home in a liturgical tradition. When they walked in, the rector greeted them and asked their names.

When she told him who she was, the rector brightened up.

“Oh,” he said, with a smile, “Like Beth Moore.” Then, having no idea who he was talking to, he added, “Come right in. We’re glad to have you.”

After the service, a handful of women who had gone through one of Moore’s best-selling Bible studies, gathered around her. They knew who she was and wanted Moore to know she was safe in that place and that there was plenty of room for her in the community.

“Can I simply ask if you’re OK,” Moore recalls one of the women saying.

In that moment of kindness, Moore says she felt seen and at home in the small congregation, which became her new church. She could just be herself, not defined by the controversies she’d been through.

“Never underestimate the power of a welcome,” she said.

The kindness of ordinary church people has long sustained Moore — providing a refuge and believing in her, even when she did not believe in herself.

Raised by an abusive father and a mother who struggled with mental illness, Moore has long said that church was a safe haven from the chaos of her home life. In her new memoir, Moore gives a glimpse into that troubled childhood and the faith—and people—who rescued her.

Displaying the skills that made her a bestselling author, Moore tells her story with grace and humor and with charity toward the family that raised her, despite their many flaws and the pain they all experienced.

Moore introduces her late mother, a lifelong chain smoker, with: “I was raised by a cloudy pillar by day and a lighter by night.”

She sums up her late father’s abusive behavior in a simple but heartbreaking sentence: “No kind of good dad does what my dad did to me.”

Moore also tells the story of how she and her sister Gay saved their parents’ marriage when their whole world was falling apart. Moore’s mother had long suspected her father of infidelity. He had always denied it and claimed Moore’s mother, who suffered from severe depression, was crazy and unstable.

Then Gay found a love letter from her dad’s mistress taped to the underside of a drawer in his desk. The two girls sprang into action, calling their father’s lover and telling her to stay away. It was an act of desperation, Moore told Religion News Service, born out of fear that the family would break apart and they’d be left homeless.

“More than anything it was a way to exercise what little power we had,” Moore said, who dedicated her memoir to her husband and siblings, including Gay and her older brother Wayne, a retired composer who passed away two weeks before the memoir was due to be published.

That call, which Moore credits to her “fearless” sister Gay, changed the course of the family’s life. Knowing the truth about her father’s infidelity gave her mom confidence after doubting herself for years.

Moore said her mother’s story resonates with people who have experienced abuse in church—or know that something is not right in their congregation—and have faced opposition. In many cases, their suspicions were correct, she said.

“But they were told they were unspiritual—that they were trying to destroy (the church),” she said. “It’s what we know now as gaslighting.”

One of the most gracious parts of her memoir comes when Moore gives thanks to two of her mentors. The first was Marge Caldwell, a legendary women’s Bible teacher and speaker. Caldwell met her when Moore was first starting out—giving devotions while also teaching an aerobics class at First Baptist Church in Houston.

Caldwell told Moore that God was going to raise her up to teach the Bible and have an influential ministry. For years, Moore said Caldwell attended her classes, even though her style was very different from her mentor.

“I would read the expression on her face—wondering, how on earth did this happen?” Moore said, laughing at the memory. “I knew she loved me so much.”

The other mentor was Buddy Walters, a former college football player who taught no-nonsense, in-depth Bible studies in Texas for years and who instilled in Moore a love for biblical scholarship. When she met Walters, Moore was filling in for a women’s Bible study teacher at her church who had gone on maternity leave. Under Walters’s tutelage, what started as a temporary assignment became a lifelong passion for Moore.

“I don’t think he would have picked me as a student,” she said. “It just was that I could not get enough.”

In the memoir, Moore, who has historically been very private about her family life, also opens up about the struggles she and her husband have faced. In the past, Moore had made comments about getting married young, and that they had struggled, but gave few details.

With Keith’s permission, she shared more in this memoir, in particular about a family crisis that was going on behind the scenes as her public ministry imploded. In 2014, two years before his wife clashed with Southern Baptist leaders over Donald Trump, Keith had been saltwater fishing, near the border of Texas and Louisiana.

While hauling in a redfish—also known as a red drum—Keith cut his hand on the fish’s spine. What seemed like a minor injury led to a life-threatening infection. As part of his treatment, Keith had to go off all other medications, including ones he had taken to manage mental illness and PTSD from a traumatic childhood accident in which his younger brother was killed.

That sent him into a tailspin that lasted for years, one the Moores have kept private until now. They decided to disclose it in the memoir, she said, because discussing mental illness remains taboo in churches.

“It’s such a common challenge and a crisis and yet we are all scared to talk about it,” Moore said. “We asked each other, what do we have to lose at this point?”

Despite the challenges of the past few years, Moore said she has not given up on the church, because it had for so long been her refuge. She knows other people have different experiences and have suffered abuse or mistreatment at the hands of fellow Christians, something she remains all too aware of.

Yet, she can’t let go.

“I can’t answer how it was that even as a child, I was able to discern the difference between the Jesus who is trustworthy with children, and my church-going, prancing-around father who was not,” she said. “There were enough people that loved me well, and in a trustworthy way, that it just won out. I can’t imagine not having a community of faith. That was too important to me to let any crisis take it away.”