We got this invitation once,” Bono tells me. He speaks the next sentence with a tone of reverence: “The Reverend Billy Graham would love to meet the band and offer a blessing.”

We’re on a video call, and the frontman for U2 is sitting on the floor in front of a green couch, his computer on the coffee table in front of him. It’s golden hour in Dublin, and the just-setting sun makes the room glow. It’s almost theatrical. There’s a twinkle in his eye, too. He knows he has a good story.

“He’s the founder of Christianity Today,” he reminds me, grinning. “I didn’t know that then, but I still wanted the blessing. And I was trying to convince the band into coming with me, but for various reasons they couldn’t. It was difficult with the schedule, but I just found a way.”

This was in March 2002, just a few weeks after U2 played their legendary Super Bowl halftime show and days after their single “Walk On” won the Grammy for Record of the Year.

“His son Franklin picked me up at the airport,” Bono says, “and Franklin was doing very effective work with Samaritan’s Purse. But he wasn’t sure about his cargo.” He laughs. “On the way to meet his father, he kept asking me questions.”

Bono reenacts the conversation for me:

“You … you really love the Lord?”

“Yep.”

“Okay, you do. Are you saved?”

“Yep, and saving.”

He doesn’t laugh. No laugh.

“Have you given your life? Do you know Jesus Christ as your personal Savior?”

“Oh, I know Jesus Christ, and I try not to use him just as my personal Savior. But, you know, yes.”

“Why aren’t your songs, um, Christian songs?”

“They are!”

“Oh, well, some of them are.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, why don’t they … Why don’t we know they’re Christian songs?”

I said, “They’re all coming from a place, Franklin. Look around you. Look at the creation, look at the trees, look at the sky, look at these kinds of verdant hills. They don’t have a sign up that says, ‘Praise the Lord’ or ‘I belong to Jesus.’ They just give glory to Jesus.”

For four decades, Bono has found himself in conversations like this one, responding to Christians who aren’t quite sure what to make of him or U2.

The band’s rise to fame coincided with the emergence of contemporary Christian music (CCM), which by 1980—when U2 released their first album, Boy—had gone mainstream. Young artists with sincere faith and fresh (often beautiful) faces were being marketed to parents and kids who were looking for music that was “safe for the whole family.”

Success in the new industry was a double-edged sword. Record labels needed bands that could play a church service and sell albums in Christian bookstores, so along with having talent and charisma, CCM artists were expected to maintain a squeaky-clean image and load their songs with overtly Christian lyrics. Some musicians jokingly refer to this as CCM’s “JPM” quotient—the “Jesus Per Minute” count in a song.

U2 evolved outside this ecosystem, and by the 1990s had become one of the biggest bands in the world. Their lyrics were often saturated with Christian imagery, biblical language, and spiritual longing, but they were just as often about sex, power, and politics.

“They formed five years before the debut of MTV and were true to their post-punk leanings,” musician Steve Taylor tells me. “They avoided letting their music be overshadowed by any overly refined band image or marketing gimmicks.”

Taylor was an “outsider’s insider” in CCM through the 1980s and ’90s, skirting the edges of acceptability with satirical and edgy post-punk and alternative music. He often skewered the hypocrisies of evangelical fellow travelers.

“CCM chose image and marketing over substance, eventually becoming a straightjacket that rewarded lowest-common-denominator thought and craft. So if the CCM industrial complex was suspicious of U2, I’m sure the feeling was mutual,” Taylor says. “That wasn’t true of the artists I knew,” he added. “U2 were our Beatles.”

AP

APYour origin story,” I say to Bono, “there’s a sense that you’re haunted by ghosts.”

He laughs. “Was it T. S. Eliot … Four Quartets?” he asks, “‘The end is where we start’?”

We were talking about Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, Bono’s nearly 600-page memoir that was just a few weeks away from its November release.

“Nineteen seventy-four took my mother away from me, but it gave me so much in return,” Bono tells me.

“My mother collapsed as her own father was being lowered into the ground, and I never spoke with her again,” he adds. “I saw her a few days later in her hospital bed as she took her last breaths. It was … I mean, people have gone through a lot worse,” he says, describing a few of the horrors he’s witnessed in his work with some of the poorest and most vulnerable people on earth.

“But yeah,” Bono continues, “death is ice-cold water on a boy entering puberty. T. S. Eliot is right, the end is where we start. You begin your meditation on life often in that kind of moment. I mean, we’re all really in denial most of our life.”

Surrender is an extended confrontation with the denial of death, beginning with a heart scare in 2016 that almost killed him. But his mother’s death looms largest in the story—her absence from their home and her presence in his heart and imagination for five decades since.

Before he was Bono, he was Paul Hewson, son of Bob and Iris Hewson. Bob was Catholic, an opera fanatic, and a man whose angular face hinted at the sharp edges of his demeanor. Iris was Protestant, mischievous, warm, and prone to uncontrollable laughter at inappropriate moments—like during an opera performance or when Bob ran a drill into his crotch and thought he’d done irreparable damage. (He was fine.)

Courtesy of Hewson Family Archive

Courtesy of Hewson Family ArchiveBono was 14 when she died. Her absence filled the Hewson home, intensifying the distance that he’d already felt between him and his father.

“There are only a few routes to making a grandstanding stadium singer out of a small child. You can tell them they’re amazing … or you can just plain ignore them. That might be more effective,” he writes in Surrender.

“The wounds that loss opened up in my life became this kind of void that I filled with music and friendship,” Bono tells me. “And really, an ‘ever increasing faith,’” he adds with a big grin, “as the Welsh evangelist Smith Wigglesworth would tell you.”

The friend that renamed him “Bono” introduced him to the kind of Christianity that has shaped his life. Derek Rowen, aka “Guggi,” was a serial nicknamer, and most of the kids who passed through their gang of friends got a new name at some point or another. (One of them, David Evans, got the moniker “the Edge” because of his sharp Welsh features. That one stuck too.)

Bono writes, “Guggi introduced me to the idea that God might be interested in the details of our lives, a concept that was going to get me through my boyhood. And my manhood.”

At the churches and prayer gatherings they attended, Bono found a direction and a name to attach to what he called an innate but “inchoate and formless” sense of the divine. It struck him to the core, and it still does. He writes,

The Bible held me rapt. The words stepped off the page and followed me home. I found more than poetry in that Gothic King James script. … I’d always be first up when there was an altar call, the “come to Jesus” moment. I still am. If I was in a café right now and someone said, “Stand up if you’re ready to give your life to Jesus,” I’d be the first to my feet. I took Jesus with me everywhere and I still do.

Iris Hewson’s death wasn’t the only earth-shattering event in 1974. Four months before she collapsed, three car bombs exploded in Dublin and a fourth in Monaghan, killing 33 and wounding more than 300.

One exploded near Dolphin Discs, the record shop that was Bono’s regular afterschool hangout, but he wasn’t there. A bus strike that same day meant he’d ridden a bike to school and back, and he was home when the bombs went off. He writes, “I didn’t dodge a bullet that day; I dodged carnage.”

Getty

GettyTwo years passed. For Bono, they were two years of internalizing trauma, terror, and grief. Then, in 1976, Larry Mullen Jr. posted a sign on the wall at his school: “Drummer seeks musicians to form band.” Among those who answered the call were Bono, the Edge, and Adam Clayton.

U2 is part of the post-punk musical era and emerged alongside bands like The Clash, Stiff Little Fingers, and the Sex Pistols. Post-punk evolved from the blunt force of predecessors like the Ramones, but the sound was more dynamic, the songs more composed. It was an era when rock-and-roll’s rebellious spirit became more political, more disgusted by the hypocrisy of elites and the abuses of the powerful.

But while their contemporaries indulged cynicism, singing about having “no reason” or “no future,” U2 sang laments, crying out, “How long?” and a mournful “We could be as one.” The band was more prophet than dissident, aware that underneath a sense of injustice was a hope for restoration.

I asked Bono about that contrast. “Even in the darker threads in your lyrics,” I say, “they don’t read like despair. They read like lament. And underneath lament, there’s always a certain kind of hope. Punk music is the sound of rebellion. You have all this trauma in your background, this sense of loss. It seems like hope itself was a rebellious act in your world at that time.”

He thinks about it for a moment, repeating a phrase. “Behind lament lurks hope. Yeah, grief becomes a kind of invocation, doesn’t it? A prayer to be filled?” He laughs. “Yeah. Punk rock prayers. That’s probably what they were.”

“It was an amazing time, punk rock,” he says. “They really inspired me. I suppose what we rebelled against in U2 was something a little more elliptical, maybe harder to follow for some, but we were rebelling against ourselves.

“I had a Bible, and I remember highlighting Ephesians 6: For our battle is not against flesh and blood, but against spiritual powers and principalities, therefore take up the full armor of God, the breastplate of righteousness, the shield of faith, the helmet of salvation, the shoes of the gospel of peace. … It made a huge impression on me. And, as an 18-, 19-year-old, I thought, That’s the real fight that’s going on. The rest is an expression of that. And, by the way, I didn’t think religious people understood their own Scripture because they were often using their religion—certainly in Ireland—as a club to beat the others down. I mean, the Catholics and Protestants … it’s kind of ridiculous, if you think about it. Yeah, we picked a more interesting fight.”

He sits up and laughs. “If you’ll spare an earnest Irish rock singer quoting their own lyrics, there’s a song on No Line on the Horizon called ‘Cedars of Lebanon,’ and I think it’s ‘Choose your enemies carefully because they will define you. Make them something interesting because in some ways, they will mind you.’ And then it goes, ‘They’re not there in the beginning, but when your story ends. Gonna last with you longer than your friends.’ I think what U2 probably got right was we just … we picked a fight with a much more interesting enemy than the more obvious for punk rock.”

It reminded me of something Bono once said in an interview with David Fricke in Rolling Stone. Fricke was covering U2’s 1992 tour for their album Achtung Baby, in which the band was indulging in wild, absurdist, self-parodying glam. Commenting on the contradiction between critiquing the excesses of rock-and-roll while also indulging them, Bono said, “Mock the devil and he will flee from thee.”

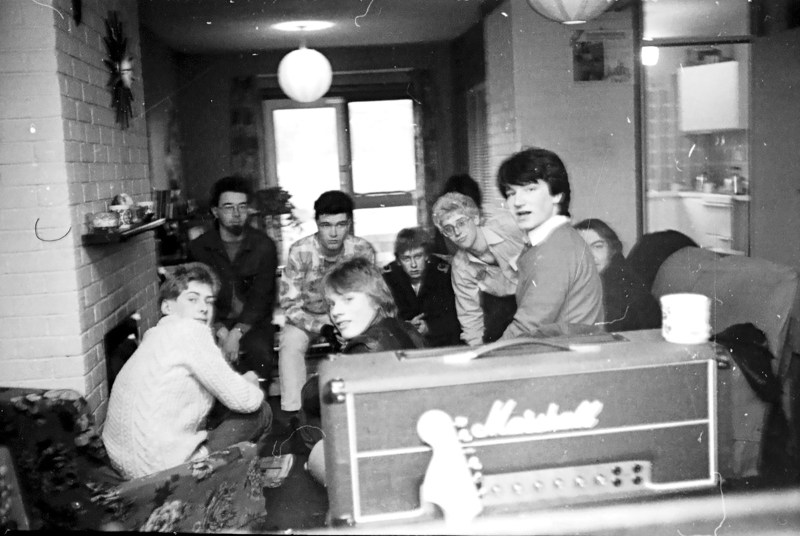

Photograph by Patrick Brocklebank

Photograph by Patrick BrocklebankAfter the release of their first record, U2 came to a crossroads. “They were seriously convicted that we were seriously on the wrong path,” Bono says, describing the leaders of the tight-knit Christian community they were a part of in Dublin. They put a lot of pressure on the band, convinced that following God’s call meant leaving the road and focusing on evangelism and church life in Dublin.

The Edge quit. Bono couldn’t imagine U2 without him, so he quit too. Larry understood. Adam did not but wasn’t going to put up a fight. They drove to the home of their manager, Paul McGuinness, and told him U2 was at the end of the road. Bono describes the scene in Surrender:

“Am I to gather from this that you have been talking with God?” he asked.

“We think it’s God’s will,” we earnestly replied.

“So you can just call God up?”

“Yes,” we intoned.

“Well, maybe next time you might ask God if it’s okay for your representative on earth to break a legal contract?”

“Beg your pardon?”

“Do you think God would have you break a legal contract? … How could it be possible for this God of yours to want you to break the law and not fulfill your responsibilities to do this tour? What sort of God is this?”

Good point. God is unlikely to have us break the law.

That conversation was pivotal. Without realizing it, McGuinness had given them the permission they needed to live in the tension of being in the world but not of it. Bono writes, “As artists, we were slowly uncovering paradox and the idea that we are not compelled to resolve every contradictory impulse.”

“His work is always ‘yes, and,’” Sandra McCracken tells me. An artist herself, McCracken takes music into church sanctuaries and smelly bars—something that would have been unimaginable for many Christian musicians a generation before her. Bono demonstrated what it could look like for Christian artists to live in those liminal spaces, letting love and imagination lead them to make music they believe in, first and foremost.

“It’s like he bled the newspapers and Scripture equally. There’s no distinction, he lives with both in front of him,” McCracken says. “And that was so compelling to me. It reminds me of the best kinds of conversations you try to have with your kids. You notice what’s captured their attention and ask, ‘What do you love about that?’ There’s a kind of generosity to it.”

It’s February 2002. The first Super Bowl after 9/11 has been a nonstop display of American flags, anthems, and former presidents. But it’s the four Irishmen of U2 who take the stage at halftime.

It’s hard to imagine another band or artist as capable of speaking to the anxieties that simmered in the American psyche after 9/11. In the two decades since the release of their first record, their punk rock prayers had made them credible witnesses for the presence of God and the hope for justice in a dark world.

When the music began, the Edge was playing the Gibson Explorer he’d bought in New York City as a kid. Bono appeared in the middle of the crowd, singing,

The heart is a bloom,

Shoots up from the stony ground.

Makoto Fujimura, the painter and author of Art and Faith: A Theology of Making, has described “culture war” as a polarized mindset, viewing culture as territory to dominate rather than a common space Christians share with their neighbors. Rather than a zero-sum game, he invites us to a posture of “culture care” and “generative creativity”—creating and collaborating to bring beauty and healing to a broken world.

“It takes a certain kind of courage to stand in the middle of devastation and not become cynical,” he tells me. “Given Bono’s story, it makes sense that he would want to speak ‘Shalom’ over the suffering in the world.”

During the halftime show, “Shalom” sounded an awful lot like “It’s a beautiful day.”

Getty / Michael Caulfield

Getty / Michael CaulfieldIt’s easy to forget the shock of 9/11 and the anxiety it left throughout the Western world. When we experience that kind of violence, we need prophetic witnesses who can not only reignite our courage and hope but also teach us to lament.

As U2 began their second song, a black scrim rose high behind them, with the projected names of 9/11 victims scrolling skyward. The Edge began the familiar percussive chimes of “Where the Streets Have No Name,” and Bono prayed from Psalm 51:15: “Oh Lord, open my lips so my mouth shall show forth thy praise.” The band crashed into the song together, Bono shouting, “America!” and offering an open-mouthed cry somewhere between a primal scream and a hallelujah.

“Artists have to learn to stand on the ashes of ground zero and believe they’ll have a new mission and a new song,” Fujimura tells me. “That means paying attention to all of it—the good and the bad. … For someone like Bono and U2, their experiences of trauma enabled them to hear a call. To pay attention to burning bushes—these places where God is speaking—and to share what they see and hear with the world.”

“Where the Streets Have No Name” is a lament, a prayer for a unity that transcends the divisions of race, class, and nation. As the song ended, Bono opened his jacket and revealed the stars and stripes stitched into its lining—one more symbol of solidarity.

Bono later described it as a night of “defiant joy.” It’s a description that suits not only that night, but all of his unique witness.

Too often, Christian artists are confronted with unwritten codes— subjects to avoid, self-images to project, messages to cram into their projects, people not to offend, and politics to endorse or avoid. Few things are more poisonous to creativity than that kind of dogmatism.

U2’s response to these confrontations has been to accept the paradox and contradiction of living in an in-between space. It’s led some to suggest they’re too Christian for the mainstream and too mainstream for Christians. It strikes me that this framework gets it exactly wrong. Living in that liminal space has made them more able to speak to both communities. It afforded them the opportunity on that night in 2002 to give the gift of grief and hope to a watching world.

Bono also found himself confronting these divisions in a new way. Near the turn of the century, he got involved with a campaign to end developing-world debt called Jubilee 2000. The success of that campaign and the exposure it gave him to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa inspired a much deeper level of commitment to activist work, eventually leading to founding the ONE campaign—including a massive effort to provide antiviral drugs to the continent.

For that campaign to succeed, he needed buy-in from conservative politicians and evangelical leaders, but polling data at the time suggested that evangelical Christians had very little interest in helping AIDS victims, including orphans. Bono took the initiative to build bridges with politicians he’d never imagined sharing a table with. He writes, “I was coming to see that the Bible was a door through which I could move with people who might otherwise stay put.”

“These are not partisan issues,” Michael Gerson tells me. He was a speechwriter and policy aide in the George W. Bush administration and has worked with the ONE campaign in the years since. “Bono found common ground with other people because of his own sense of human dignity, which is rooted in the Bible.”

That’s how Bono found himself being prayed over in the office of senator Jesse Helms (who was one of the inspirations—and not in a good way—for U2’s anti-war song “Bullet the Blue Sky”). It’s hard to imagine a politician with views more diametrically opposed to Bono’s. Helms had called AIDS “the gay disease” and had been an opponent of civil rights legislation for decades. “And here he is,” Bono writes, “putting his hand on my head.”

Helms was praying for him.

“He has tears in his eyes and later he will publicly repent of the way he has spoken in the past about AIDS. As big a shock to the left as to the right. It was the leprosy analogy from the scriptures that moved him. He had to follow his Jesus there.”

Throughout the Bush administration, Bono and others in the ONE campaign built bridge after bridge, resulting in more than $100 billion of taxpayer money being allocated toward efforts to prevent HIV transmission and provide treatment.

“The thing that turned America around,” Bono tells me, “that helped inspire a conservative president of the United States to take up the fight against HIV/AIDS and lead the world in what was the greatest, largest intervention in the history of medicine, were conservative Christians.”

I tell him I’m fascinated by these stories, especially in our current polarized times.

“I will define myself as the radical center,” he says. “Having your faith hijacked by politics is something we all need to be really careful of.”

If hopeful lament was an act of rebellion in 1981, when Boy was released, maybe being in the radical center is punk rock in 2022.

“I don’t think we should allow ourselves into this binary view of the world between progressive and conservative. I think that’s very divisive,” he says. “We’ll find common ground by reaching for higher ground.”

“We need to get through it to a place of wisdom,” Bono continues. “And I predict revival.” In fact, he predicts that churches, of various denominations, “could be filled instead of emptied. But it depends on how they’re used. We have to hope that people will live their faith, rather than just preach it. We have to preach it. If you’re a preacher, preach it. But if you can’t live it, stop.”

When I first envisioned interviewing Bono, I found the scale and scope of his life kind of overwhelming. He’s not just one of the world’s biggest rock stars— he’s one of its most visible and effective activists. And of course, in reading Surrender, I was struck by how his extraordinary life is also full of the ordinary complexity of our human experience—love, loss, grief, grace, wounds, redemption.

“I wanted to explain what I’ve been doing with my life to my family and friends and fans,” Bono says of Surrender. “I also wanted to explain to my family what I’ve done with their life. It was they that permissioned me to be away, whether it was the traveling circus that was U2 or my activism. I just wanted them …” He pauses for a long beat. “I wanted them to understand what I was doing with my life.”

As someone who’s spent most of my life identifying with the spiritual ethos of Bono’s lyrics, I think it makes perfect sense that Bono would write a spiritual memoir. It’s a genre that Augustine probably didn’t invent but certainly set the standard for in Confessions. Augustine’s expressions of desire, regret, and hope resonate to this day because they reflect the experience of every soul that allows itself to feel its longing for God. Augustine’s most famous prayer, “Our heart is restless until it rests in you,” sounds an awful lot like U2’s “I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.”

Even in Surrender’s final pages, Bono identifies himself as a pilgrim, not a sage—someone still on the search. He tells a story about seeing his son play with his band, Inhaler, and the conversation they had afterward. Bono tells him, “To be yourself is the hardest thing, and it’s easy for you. I’ve never once been myself.”

I tell Bono that line really surprised me.

“The word surrender still seems out of reach for me. The integratedness you expect from a person who’s been made whole by their faith, I’m probably missing. I have the joy, I have some insights, I have a lot. But being comfortable in my skin is what I was talking about,” he says.

“You know, the U2 thing on stages … a lot goes in,” he says. “We really have to prepare ourselves before we walk out on stage. We have to pray for each other. And it’s like, ‘Come on, lads. It’s just a rock-and-roll show. Get over yourself.’ But we can’t do it without that. I was just speaking to my high school yesterday, to the sixth-year students. I was reading them the book; I was so nervous.”

He takes a slow breath. “But I will tell you, deep down, there is an anchor,” he says. “I’m fixed to a rock, and that rock is Jesus.”

Mike Cosper is director of CT Media.