This article is the second of a four-part series based on the upcoming book by Marvin Olasky and Leah Savas, The Story of Abortion in America: A Street-Level History, 1652–2022.

Millions of expectant parents have now seen ultrasound video of their unborn children. The technology is new, but the desire to see what’s invisible is not. We can trace six steps in prenatal visualization technology during the past 170 years—and then wonder what the seventh will be.

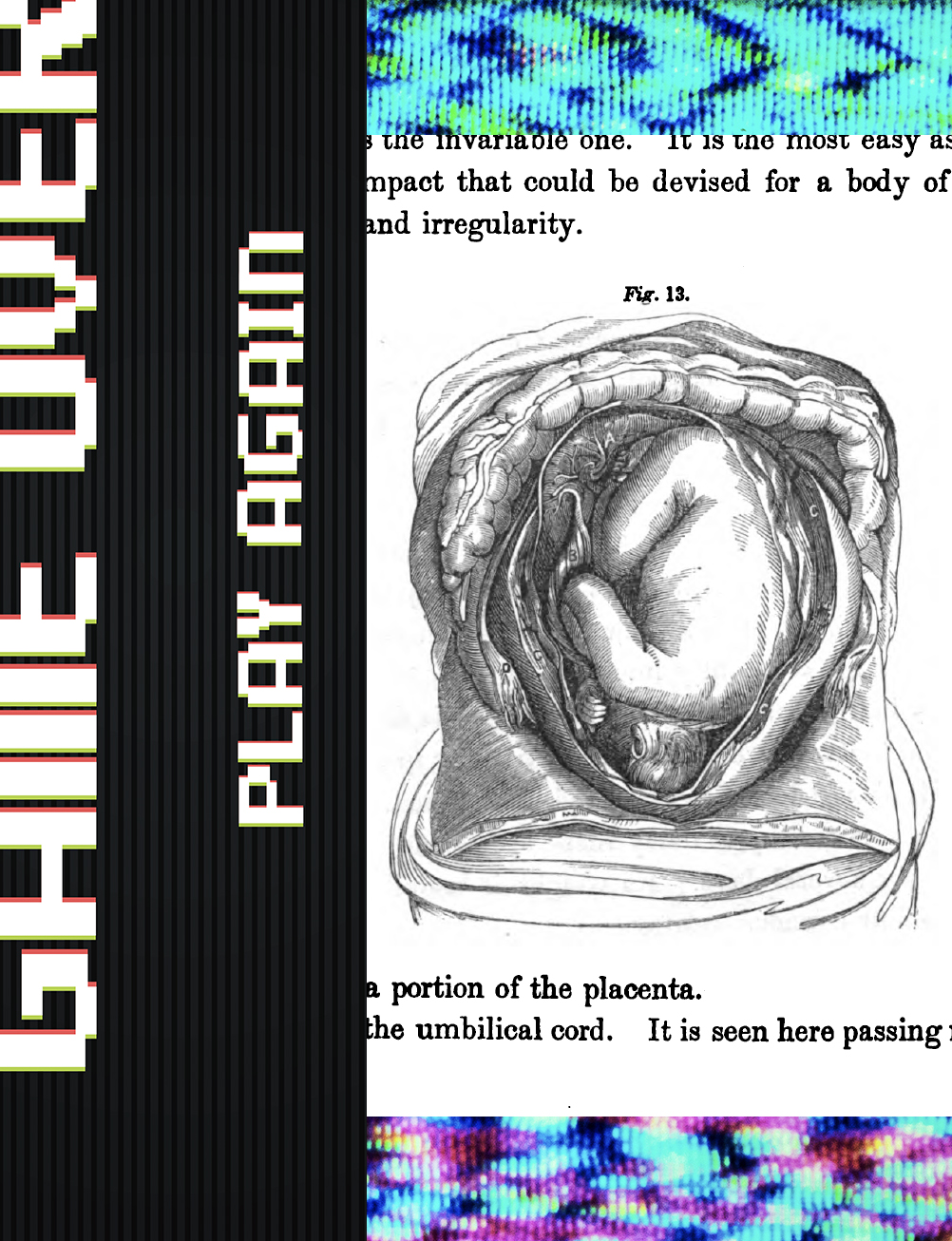

The first three steps involved word pictures. Stephen Tracy’s The Mother and Her Offspring (1853) was one of the first books I’ve seen that took readers week by week and month by month through the early development of unborn children:

At forty-five days … the head is very large; the eyes, mouth, and nose are to be distinguished; the hands and arms are in the middle of its length—fingers distinct. … At two months, all the parts of the child are present. … The fingers and toes are distinct. … At three months, … the heart pulsates strongly, and the principal vessels carry red blood.

The second step emphasized woman-to-woman lectures about the unborn. In the 1850s Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female to receive a medical degree in the US, pleaded with mothers to “look at the first faint gleam of life, the life of the embryo. … The cell rapidly enlarges. … Each organ is distinctly formed. … It would be impious folly to attempt to interfere directly with this act of creation.”

In the 1860s Anna Densmore French explained fetal development to teachers who planned to pass on this knowledge to their teenage students. French said, “Women would rarely dare to destroy the product of conception if they did not fully believe that the little being was devoid of life during all the earlier period of gestation.”

She showed week by week that “life processes were going on from the very beginning of embryonic development.”

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Itsarasak Thithuekthak / Tetra Images / Getty

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Itsarasak Thithuekthak / Tetra Images / GettyIn the 1870s Rachel Gleason gave talks warning that women who aborted would feel what we today call post-abortion syndrome: “Remorse for the deed drives women almost or quite to despair.” And at century’s end, Prudence Saur lectured about life beginning “from the moment of conception, [as] modern science has abundantly proven. It follows, then, that this crime is equally as great whether committed in the early weeks of pregnancy or at a more advanced period.”

Books for children and teenagers were a third step. Mary G. Hood’s For Girls and the Mothers of Girls: A Book for the Home and the School Concerning the Beginnings of Life (1914). Here’s how she introduced the first moments of fetal anatomy:

The two cells unite, and become one, much as two drops of water, when they come into contact, merge into each other and become one drop. Thus the two cells, which in their origin come from two different beings, unite to form the new cell, which will result in a completely new and different human being.

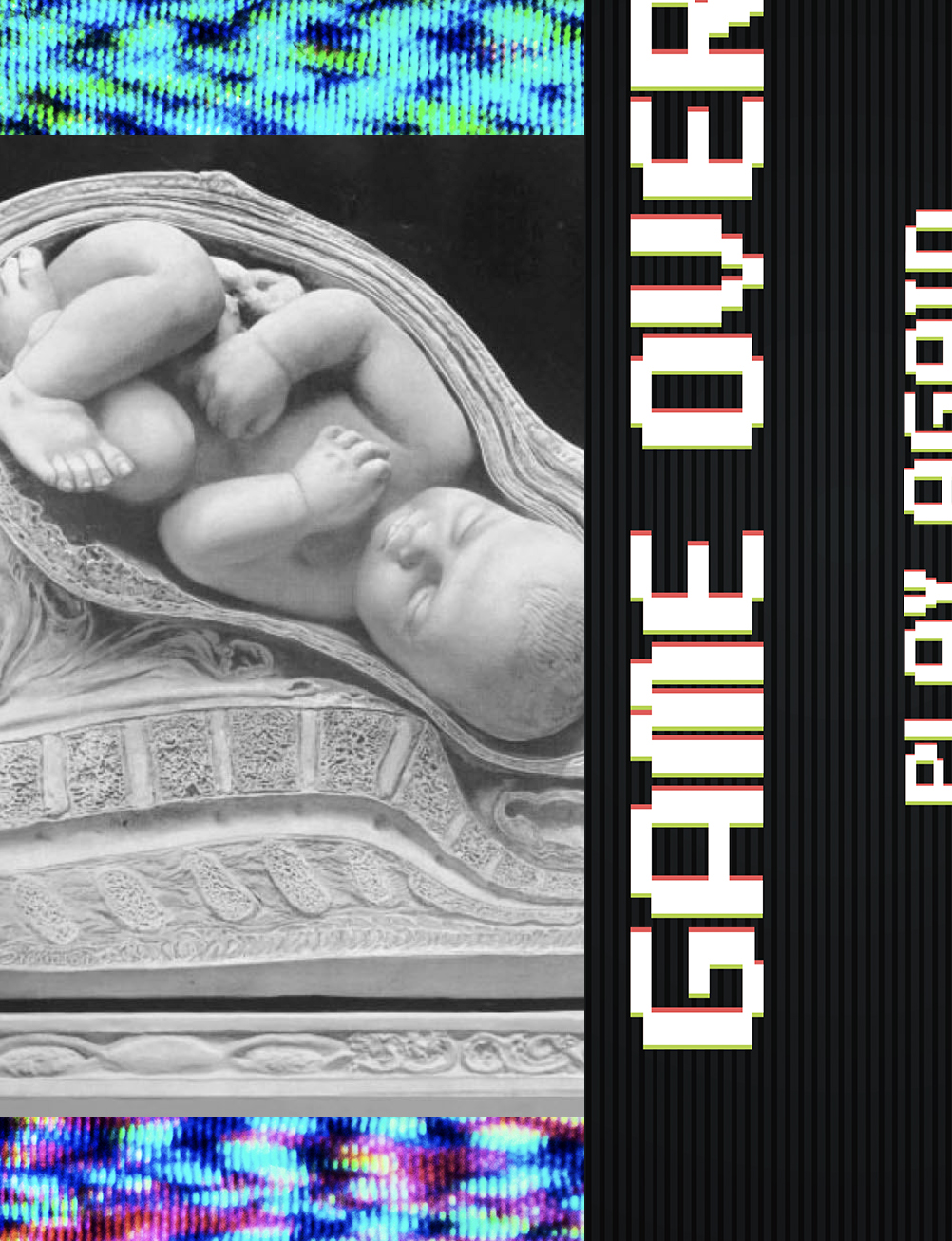

The next three steps involved showing rather than telling. At the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, more than two million people viewed the most realistic and beautiful sculptures of unborn children ever created.

People stood in line for hours “with wonder on their faces” to see what before was invisible, as historian Rose Holz recounts: “Neither rain nor shine stopped the crowds from coming; nor did the occasional stampede.” The sculptures combined scientific accuracy with artistic beauty to depict development as a romance beginning with conception and unfolding all the way to birth.

Ironically, the obstetrician in charge of the sculpture project, Robert L. Dickinson, wrote (but did not publish) a personal essay, “Blessed Be Abortion,” that praised abortion as a relief from “intolerable” burdens like “added maternal care” or “life-long shame.” During the 1940s he was a Planned Parenthood senior vice president and director. (It takes all kinds of people to increase pro-life understanding.)

It also takes all kinds of motives. Like Dickinson, the Gerber Products Company also had commercial interest in distributing at the World ’s Fair and elsewhere a How Does Your Baby Grow? pamphlet with photos of the sculptures. It explained, “A baby ’s life begins not when he puts in his squalling appearance but at the moment the sperm (from the father) meets the egg (from the mother) in the Fallopian tube.”

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Itsarasak Thithuekthak / Tetra Images / Getty

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Itsarasak Thithuekthak / Tetra Images / GettyAfter the fair Gerber added a warning—“Abortions Are Dangerous!”—that summed up the physical and psychological consequences for women who “live with unhappy memories of what might have been. If you are thinking about an abortion—stop! Go to your family doctor. … Don ’t make a move you ’ll regret.”

Meanwhile, the sculptures traveled to medical and public health institutions in many cities. Then came mass reproduction and eventually low-cost plastic models.

The fifth step came from abroad. Swedish photojournalist Lennart Nilsson during a visit to New York told editors of Life magazine that he wanted to photograph unborn children. The editors were technically skeptical but supportive: That partnership led to a Life cover in 1965 featuring a Foetus 18 Weeks photo of an unborn child floating within an amniotic sac. The issue was Life’s all-time fastest seller at checkout counters. Nilsson’s A Child Is Born became one of the top-selling illustrated books of all time.

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Itsarasak Thithuekthak / Tetra Images / Getty

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Itsarasak Thithuekthak / Tetra Images / GettyThe sixth step is ultrasound imaging, which has been worth more than a thousand words in changing the hearts of some who were contemplating abortion. Some states now require abortion providers to perform ultrasounds and show them to patients, leading pro-abortion advocates like the Guttmacher Institute to complain that “the requirements appear to be a veiled attempt to personify the fetus and dissuade an individual from obtaining an abortion.”

What will the seventh step be? Every technological development adds opportunities for both sin and grace. Some video games now have characters like Giant Baby Fetus Monster Boss. An Argentinian pro-abortion activist created a game where a player wins by shooting an unborn baby with a shotgun. The game then compliments the player for defeating “fetito” (little fetus) and urges him to send an abortion pill “to those in need so they might defeat it too.”

Will pro-life gamers create lifelike video games that lead to more empathy for unborn children?

Whether or not such creativity occurs, thinking about different steps toward visualization reminds us that America’s abortion tragedy did not begin with Roe v. Wade and it will not end with a Roe v. Wade reversal. Legal change will help to save some, but many hundreds of thousands will still die as long as mothers (and fathers) visualize them not as sucking their thumbs but sucking life out of their parents.

Content adapted from The Story of Abortion in America by Marvin Olasky and Leah Savas, ©2023. Used by permission of Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.