Seven years ago, First Presbyterian Church of Deming, New Mexico, had to replace the rope hanging from its bell tower. After 75 years of regular use, it had finally unraveled. The bell has been ringing since the Pueblo mission-style building was constructed in 1941, and the church itself dates back further, to the turn of the 20th century.

Not much else has endured like the bell. Today, the church building’s original adobe walls are covered by white paneling and a powder-blue roof. Out front, the steps leading to the entrance have been replaced with a wheelchair ramp. There was a time when the congregation nearly filled its 200-person sanctuary. On a recent Sunday, five people showed up.

“That’s the lowest it’s ever been,” Liv Johnson said. In the three decades since she started as secretary at First Presbyterian, Johnson has watched a slow trickle of people leave. “When I first came here, the average attendance—because I had to do that report—was 82,” she said. “I remember having 35 kids for Sunday school, and now we have none.”

Still, Johnson doesn’t despair. She believes strong, stable leadership could turn things around. But recently, consistent leadership has been difficult to come by.

In 2018, First Presbyterian’s pastor, Adam Soliz, passed away after a short battle with lung cancer. A new, younger pastor took over the congregation just as the COVID-19 pandemic decimated church attendance. The new pastor reconsidered his vocational trajectory, and in August of 2021, he accepted a better-paying job and left.

Unfortunately, replacing a pastor is far more difficult than replacing a bell rope. And the longer it takes, the more it costs.

To make its monthly budget, the church scrambled to find a family to rent the parsonage. “I have to play landlord. I’ve even preached,” said Johnson, the only person left on staff. With the help of guest preachers, they’ve had sermons every week. But many former attendees say they won’t come back until the church finds a permanent pastor.

Last fall, Dale Cook, the head deacon at a Presbyterian church in Las Cruces, New Mexico, drove the 60 miles to Deming to preach at the Deming church. They liked him and asked if he would consider preaching on a regular basis.

Cook is now working to become a commissioned lay pastor for First Presbyterian of Deming. He believes God has been preparing him for this role since he was a kid. “I grew up in the home of a Southern Baptist minister. He was with the Home Mission Board, and he went around jump-starting small churches and rebuilding older churches that had lost all their congregation,” he said.

Cook plans to minister bivocationally so he can move into the parsonage and support the church with his rent and proximity. “I was told, ‘If you move up there, you’re going to be right next door to the church. You’ll be expected to be on call 24/7.’ And I said, ‘Well, that’s what I always thought a minister did anyway.’”

First Presbyterian’s struggles to find and keep a pastor are not uncommon in small churches across the United States. And according to many experts, they may become even more common as the nation potentially approaches a surge of pastoral resignations.

In his list of “10 Things Trending in the Church for 2022,” author and researcher Thom Rainer predicted a looming pastor shortage: “Departures of pastors will increase by 20%. The Great Resignation will hit pastors hard.” And in September of 2021, author and pastor Dane Ortlund tweeted, “A tidal wave of pastor resignations is coming in 2022.”

If they’re right, more churches than ever may find themselves with a leadership deficit—and few will have a Dale Cook to take the reins. A nationwide pastor shortage could be a death knell for many smaller churches.

But a deeper look at pastoral employment data suggests that, while tales of a Great Ministry Resignation are being told everywhere from The Washington Post to The Wall Street Journal, there’s reason to question whether a mass clergy walk-off is really on the horizon. There’s also reason to think that the more likely alternative—a future in which pastors aren’t quitting—could be even more concerning.

“The great resignation is coming,” warned Texas A&M professor Anthony Klotz in a May 2021 Bloomberg article about American workers at large. “When there’s uncertainty, people tend to stay put, so there are pent-up resignations that didn’t happen over the past year.”

It didn’t take long for this resignation backlog to unjam. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), more Americans left their jobs in April 2021 than in any month on record. A disruption that seemed to almost single-handedly dominate the news cycle, the Big Quit gained momentum into the summer, peaking at 4.5 million people quitting their jobs in November.

These resignations hit some professions harder than others. The health care sector bled hundreds of thousands of employees and spiraled into a crisis it has yet to recover from. Many of the nurses who left are not looking back.

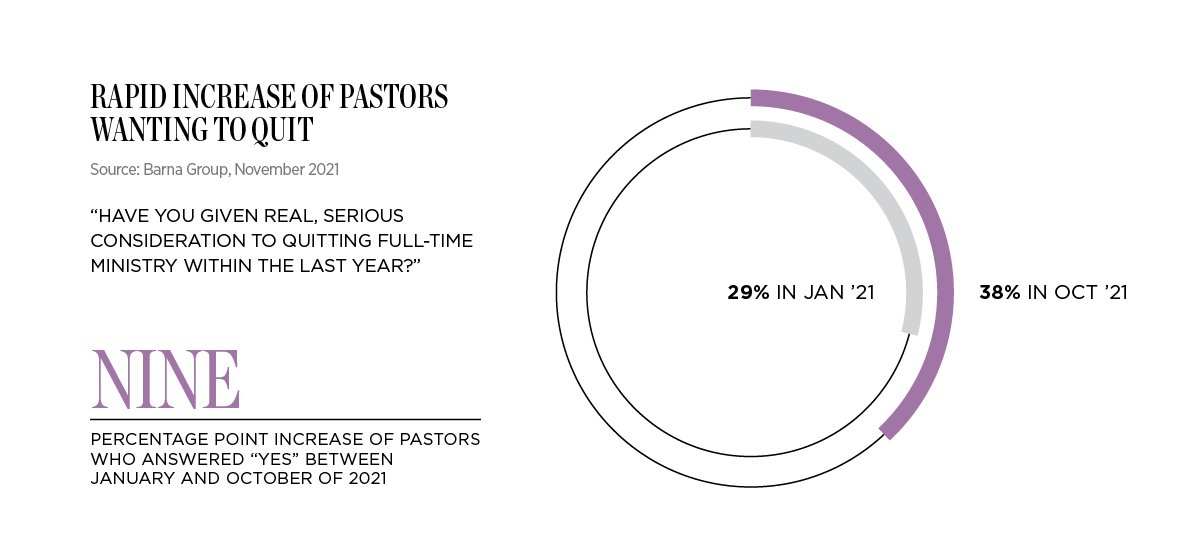

There are far fewer pastors in America than nurses, but some anticipate a similar exodus from pastoral ministry. As Christianity Today has reported, an October 2021 Barna Group survey revealed that 38 percent of Protestant pastors had seriously considered quitting full-time ministry that year—nearly a third more pastors than when Barna asked the same question that January.

At first glance, this tracks with what we’re seeing in America broadly. A Yahoo Finance/Harris Poll survey last year found that 37 percent of US workers “are either thinking of leaving their current jobs or are already preparing to make the move.”

But the Great Resignation is more complex than its name implies. Think of it more as a Great Reshuffling. In an article for The Atlantic, Derek Thompson wrote, “The increase in quits is mostly about low-wage workers switching to better jobs in industries that are raising wages to grab new employees as fast as possible.”

Despite higher-than-ever levels of exits in hotels and restaurants, the accommodation and food services sector grew by two million employees last year. It’s a job-seeker’s market, but the dramatic worker shortages we’re seeing in health care are an outlier in the Great Resignation.

While the nursing shortage is well documented, there’s less evidence that pastors are leaving ministry in droves—at least for now.

In a remarkably thorough survey of the available ministry attrition data, Duke University’s Allison K. Hamm and David E. Eagle concluded last year that “best estimates suggest that annual attrition rates across Protestant denominations in the United States are generally around 1%–2%, with occasional context-specific anomalies.”

This aligns with a 2015 Lifeway Research study that found a 1.3 percent annual attrition rate among evangelical and Black Protestant senior pastors. So if we’re looking for any spike in clergy leaving ministry, 1 or 2 percent annual attrition is a reasonable baseline to start from.

“I was walking toward the church one day, and I felt something inside of me snap, like a rubber band had been stretched too far.” Jonathan Dodson

To learn how the past two years have affected pastoral employment, consider BLS’s data on clergy. For the first time since 2011, its estimate for national employment of clergy dropped in 2020, from 53,180 in 2019 to 52,260. It dropped again in 2021 to 50,790. We should look at those numbers with a raised eyebrow, though. The Southern Baptist Convention alone had 47,592 churches in 2020, so the BLS is only measuring a fraction of all US clergy.

In a national employment matrix showing next-decade employment projections, the BLS uses a more realistic number for total 2020 clergy employment: 260,600, up from 243,900 the previous year. They predict a slower-than-average 3 percent growth rate between 2020 and 2030, but that’s far from a shortage.

A more reliable measure comes from a 2021 Lifeway Research study that mirrors the one from 2015. It found that, over the past decade, only 1.5 percent of evangelical and Black Protestant senior pastors left ministry each year—a statistically insignificant increase from the 2015 study and well within expected attrition rates.

“Typically, when [pastors] step away from a church—if it’s a really bad situation there—they’re stepping into another pastoral role,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “And that’s still what we see today.”

A survey by Scott Thumma and the Hartford Institute for Religion Research conducted during the summer of 2021 revealed that, while 37 percent of pastors seriously considered leaving ministry in the past year (similar to Barna’s findings), most of them did so only once or twice in fleeting moments of unusually high discouragement. Thumma concludes, “Overall, our data just doesn’t provide much evidence of a pending mass exodus of clergy.”

In fact, there’s reason to believe senior pastors are more reluctant than usual to leave their churches. Sarah Robins, former vice president of client relations at pastor search firm Vanderbloemen, said the company has struggled in the past two years to find senior pastor candidates willing to consider other ministry positions. “The idea of leaving their church in the middle of what we’re going through is too much for them,” Robins said.

Angie Ward, assistant director of the doctor of ministry (DMin) program at Denver Seminary, has also seen transition hesitancy in her students, many of whom are working senior or solo pastors. “People aren’t making big transitions, whether that’s starting school or moving to a different church. They don’t feel like they’re in a stable enough place to leave,” she said. “Among my students, more are saying, ‘I can’t do DMin right now because I need to drill down with my congregation.’”

When it comes to overall ministry employment, fewer entrances can account for lower numbers just as much as more exits. Among Protestant and nondenominational seminaries that are part of the Association of Theological Schools (ATS), MDiv enrollment dropped slightly in the 2020–21 school year. But that’s nothing new—MDiv enrollment has trended down almost every year since 2013.

A clearer slip appears in the number of students graduating. MDiv and total degree completions at ATS schools in the US both dipped in the 2020–21 year, with only general theological degrees seeing a small increase. It’s possible some students were waiting to see how the pandemic would progress before completing their programs.

Even if we haven’t seen a dramatic increase in pastoral attrition, many people believe it’s still coming. Sean Nemecek serves as the West Michigan regional director for Pastor-in-Residence Ministries, where he works with pastors who have been let go from their churches. He is bracing for a wave of pastors to leave in the next year or two and has noticed a shift in the conversations he’s having with the pastors he coaches.

“In the culture at large, we’re seeing an increase in people saying they expect their employers to treat them well. Fair pay and time off. Flexibility and working from home,” Nemecek said. “A number of pastors are saying the same type of thing to me: They’re tired of being woefully underpaid or having to work a second job to support the ministry.”

If the bubble does burst later this year or next, all eyes are on three demographics: pastors early in their careers, those nearing retirement, and bivocational ministers.

Young, beginning pastors are often told that the first five years of ministry will weed out those who aren’t in it for the right reasons. Some put the five-year attrition rate at as high as 85 percent. But most reliable studies estimate that number actually ranges from 1 percent to 16 percent. (Compare that to the 44 percent of new public and private school teachers who leave education before their fifth year ends.)

Still, the past two years have gnawed at younger pastors more than established ones. Barna discovered that pastors under the age of 45 are more likely to consider quitting full-time ministry (46%) than pastors 45 and older (34%). And in the 2021 Lifeway Research survey, pastors ages 18–44 were more likely than pastors over age 65 to agree that “the role of being a pastor is frequently overwhelming,” that “I frequently get irritated with people at the church,” and that their congregations have experienced conflict over politics.

As part of his doctoral work, Prince Raney Rivers, senior pastor at Union Baptist Church, studied postpandemic burnout among African American Baptist pastors in North Carolina.

“I was surprised that the younger pastors—those under 40—reported more cynicism and a greater sense of depersonalization than older pastors in the study,” he said. “A certain amount of attrition happens, so if you make it to 60 or 65 years old, then you’ve already worked through those issues and you have built-in resilience. Maybe younger clergy are less patient with the time it takes to bring about change in a congregation. If you think you’re going to save the world in two years and everybody takes seven just to know what needs to be saved, that’s going to be a real challenge.”

Rivers continued, “I find that younger clergy in particular, who have more of an activist mindset, may have felt led to lean into that activism, but that may not have been where their congregations were ready to go at that time. That made some clergy say, ‘You know what, I think I would find it more life-giving to use my gifts and talents and calling outside of the church because of the pressure I’m getting not to do certain things from within the church.’”

But young pastors aren’t the only ones Rivers identified as standing on the edge of burnout and resignation.

“I have several friends who told me recently that they’re going to retire a lot sooner than they ever expected,” he said.

By this point, the aging of American pastors is a well-established phenomenon. Baby boomers have stayed in ministry longer than expected, and we should expect to see a natural rise in retirements as they finally transition out of lead roles. But the pressures of the past two years could cause many to retire early.

At Vanderbloemen, Robins recalled having more conversations with baby boomer pastors who were calling it quits earlier than expected.

She remembers one particular pastor in his early 60s. “He was so worn out from leading that church,” Robins said. “He had a couple board members say, ‘From the pulpit, you need to endorse Trump.’ And he said, ‘That’s not my job as a pastor.’ And they said, ‘Well, then we’re leaving your church.’ He had a room full of elders who loved him, but he was just so exhausted.”

Between the 2015 and the 2021 Lifeway Research surveys, the number of pastors who had retired in the previous decade rose from 17 percent to 20 percent. “That would be within the margin of error. But we do see it starting to inch up there,” McConnell said. “Between 1 in 5 and 1 in 4 Protestant pastors is of retirement age. If all of those at retirement age in any given year were to decide to retire, it would create a huge hole that couldn’t be filled.”

As the Great Resignation creates job openings across sectors, some experts believe that pastors with a second, “tentmaking” job are also more likely to leave ministry in the next year, since they already have one foot outside the ministry bubble.

“Some of the pastors I coach are bivocational,” Nemecek said, “and one of the things I’m hearing is, ‘Maybe I should just invest full time in my other job and pull away from the church for a little while.’”

Bivocational pastors are at a higher-than-average risk for burnout if they juggle long hours working a full-time job and pastoring a congregation. Curtis Dunlap, family life pastor at Epiphany Fellowship Church in Philadelphia, said his full-time staff position is atypical at a mostly Black church like his. “The vast majority of pastors I know in urban cities that are ministering to people of color are bivocational,” he said.

Dunlap pointed out that it’s harder for bivocational pastors to schedule vacations or sabbaticals. “Pastors like me who are full time have more flexibility to control our schedules,” he said. “Sometimes in church culture, if the lead pastor is not preaching, a lot of people don’t show up. That’s a lot of pressure—especially in a smaller church where you have to think about how that will affect giving week to week, and especially in the summertime when giving already drops.”

Burnout, discouragement, and emotional exhaustion can devastate pastors and congregations if left unaddressed. Even if most of the 38 percent of pastors who considered quitting full-time ministry last year never actually leave, we should still ask why that number rose so quickly in 2021. Perhaps our greatest concern shouldn’t be empty pulpits, but rather empty pastors standing in them.

Jonathan Dodson has one word to describe his experience in ministry over the past two years: “excruciating.”

“I thought about quitting multiple times,” he said. “Put me in that 38 percent.”

God captivated Dodson’s heart at the age of seven. He read missionary biographies and tried to meet with missionaries when they came to town. “It was a sovereign planting of the Lord in my heart to this kind of missionary spirit,” he said. As an adult, Dodson planted City Life Church in the heart of Austin, Texas.

But in the years leading up to the pandemic, Dodson’s ministry enthusiasm took a hit from a series of grueling events, starting with a particularly distressing meeting. Before terms like social distancing or coronavirus entered the American vocabulary, Dodson sat down with a couple in their mid-50s, mentors at the church who had contacted him to share that they didn’t believe in the Trinity anymore.

At that meeting, the warm, Bible-loving people Dodson had known for years turned icy and cold. “When I asked to pray,” Dodson said, “he pinned me to the wall with daggers in his eyes.” The couple had discovered a rabbi on the internet whose aim was to deconvert Christians. “They swallowed it hook, line, and sinker.”

That was the first in a series of conversations with deconverting congregants. “That’s one of the worst things—for pastors to see people they love abandon the Messiah,” Dodson said. “It’s just heartbreaking.”

Then came COVID-19 quarantines, which further battered his spirits. “You’re preaching to a cold, dark camera instead of living, beating hearts in front of you, Sunday in and Sunday out,” he said.

After the 2020 presidential election, Dodson saw an increase in criticism from politically left-leaning congregants. “We are a gospel-centered church,” he said. “We care about justice, racial justice. We’ve been growing in our expression of that, to be sure, but this group became highly critical. There were lots of critiques. Three-page emails. Anger. ‘Why aren’t you doing this?’ ‘Why aren’t you doing that?’ And then people began to leave the church.”

A glimmer of hope came as the pandemic seemed to subside and City Life Church began gathering in person again. But then the delta variant arrived. This time, criticism came from the right, and the target was masks.

“We rent a facility downtown. We’ve been there 10 years, and we have to abide by their policies,” Dodson said. “We received bizarro emails from people we’ve known for 10 years. I’ve dedicated their children. I’ve mentored them, walked with them through seasons of hardship, and poof: ‘If we have to wear masks, then we’re out of here.’

“The density of those kind of encounters in the last two years was so atrophying and exhausting,” he said. “One of the real hard things for pastors across the country is that our role tends to be treated as relationally disposable. We value pastors when they give us what we need or want, but when we think we need something else, suddenly they’re inhuman. They’re a religious commodity to be unsubscribed from.”

And then, on top of everything else, the facility City Life Church rented kicked them out.

“I was walking toward the church one day,” Dodson said, “and I felt something inside of me snap, like a rubber band had been stretched too far. I became emotionally decoupled from the church. It was like the reserves were gone. The thought of walking into a room full of Christians I’m responsible for was harrowing. I’ve never had that kind of experience.”

Discouragement and thoughts of leaving ministry aren’t uncommon in the life of a pastor. Charles Spurgeon described them as “the minister’s fainting fits.” He wrote, “It is not necessary by quotations from the biographies of eminent ministers to prove that seasons of fearful prostration have fallen to the lot of most, if not all of them.”

Eugene Peterson, reflecting on his pastorate at Christ Our King Presbyterian Church, said, “I can think of three times since I’ve been here when I was ready to leave.” During one such episode, on his way to comfort the family of a woman killed in a car accident, Peterson thought, “Lord, I can’t do this. I don’t want to be a pastor anymore. I just can’t enter into that deep pain again. Or if I can, I don’t want to. I just don’t want to do this anymore.”

What’s unusual about our current situation, though, is the sheer number of pastors wanting to leave ministry simultaneously throughout the US and across demographics and traditions.

But whether all those pastors will actually jump ship is, in a sense, less important than understanding why they’re so eager to get out. When so many pastors are discouraged or burned out, it is—ironically—not especially pastoral to fixate on whether a ministry labor shortage is brewing.

Instead, we should be asking, What is happening to our pastors? We should ask because we care, certainly. But the stakes are bigger than any single leader.

It’s well established that unhealthy leadership often leads to an unhealthy organization. Rivers, the North Carolina pastor, said, “If the pastor is less available, if they’re pulling back, that’s going to spread over into less enthusiasm for the mission of the church, the vision of the church. It will probably cause greater conflict and less healthy ways of managing conflict.”

But there’s a more sinister risk that accompanies burnout: “Burnout makes a pastor vulnerable to all kinds of ethical and moral failure,” Rivers said. “The more emotionally exhausted you are, the more vulnerable you become to making choices you would not make at healthier times and in a healthier frame of mind.”

Nemecek has seen much the same thing in the pastors he’s coached.

“A lot of the moral failures and spiritual abuse we’re seeing in the church right now have some foundation in the culture that pastors are working in,” he said. “As I talked to pastors who have experienced moral failure, they didn’t start off as spiritual predators. They found themselves in a place where they were searching for some sort of affirmation and ended up in sexual temptation or other types of moral failure because of it.”

Ministry leaders caught having affairs often use the excuse that they felt they were owed some happiness after their unacknowledged hard work for the church. Although he wasn’t a pastor, Ravi Zacharias reportedly used this logic to justify his sexual abuse. According to a CT investigation, he told one woman that “the Lord understood what he had sacrificed and implied their sexual exchanges were God’s way of rewarding him.”

Robins said that at Vanderbloemen, “Almost every single time we’ve walked into a church and helped them navigate replacing a pastor after a moral failure, that has been correlated with extreme exhaustion in the senior pastor. That does not excuse bad behavior, but there’s a correlation there. Even monetarily—‘I’m exhausted. I deserve to spend this kind of money on this sort of thing because of all that I’m doing for this church.’”

It would be unwise to attribute all spiritual abuse and moral failure in ministry to emotional exhaustion, but if we’re considering how burnout can wreak havoc on churches, those things should top our list.

Burnout is like a pressure cooker. Tension slowly builds, and without some kind of release valve, the temperature of discouragement becomes unbearable. In his Atlantic article, Derek Thompson wrote, “Strange as it sounds, the increase in self-reported burnout is happening in industries where workers are less likely to quit.” And pastoral ministry isn’t a vocation that people quit often.

The reasons for this are many and complex. “Few vocations are as deeply vocational as pastoral ministry,” said Ward at Denver Seminary. “There’s this deep sense of calling by God and to the people of God. It’s not something you just shake off and go into insurance.”

There are numerous reasons pastors might stay too long: a sense of obligation, or unhealthy ownership, or misunderstood duty to God. Financial struggles can also keep the exit locked as pastors approach retirement.

In a 2017 report on the economic challenges facing pastoral leaders, C. Kirk Hadaway and Penny Long Marler wrote, “In most surveys conducted by projects in the National Economic Initiative, retirement saving is the most serious financial concern expressed by clergy.” Across the US, pastoral salaries are relatively low, and retirement benefits are often nonexistent.

When Nemecek experienced his own season of burnout and stepped away from congregational ministry, he discovered another reason many pastors find it difficult to leave, even for a season.

“There’s a lot of stigma,” he said. “People assume that whenever a pastor says, ‘I’m stepping out of ministry,’ they must have some secret sin, or just couldn’t hack it, or were never really called in the first place. But when you actually sit down and ask, ‘What’s going on?’ a lot of times, they’re actually making really strong moves in their faith in Christ.”

Dodson put it like this: “Just because you’ve lost the power to do ministry doesn’t mean you’re in sin. It may be, in fact, that you’ve been sinned against.”

Forces both internal and external pull at pastors—and they’re nothing new in the church. In 1589, the 70-year-old Genevan reformer Theodore Beza faced many of the greatest challenges of his long ministry tenure.

His health was waning, yet his duties seemed heavier than ever. He was providing pastoral care for situations as awful as a cobbler demanding a divorce from his wife who had been raped by soldiers and may have gotten pregnant. And he was still expected to preach several times a week and give theology lectures at the Genevan Academy.

“Remember to pray more and more for your friend Beza as he looks down the final stretch of his course,” he wrote to a friend. “Although I am worn out, the Lord has never before given me a heavier load to carry.”

The next year, he asked the council of Genevan pastors if he could step down from his ministry obligations. Scott M. Manetsch writes, “The Genevan clergy agreed to relieve him of his weekday preaching responsibilities, but insisted that he continue his lectures at the academy and his Sunday sermons. Geneva had too few ministers and professors to permit the old reformer a respite.”

Even given history, something different is afoot today. Pastors’ pressures feel greater than they have in generations. Thumma’s survey found two-thirds of pastors called 2020 “the hardest year in their ministry experience.”

COVID-19 might seem the obvious culprit. But none of the pastors interviewed for this story identified the pandemic as the primary cause of their burnout. It depleted their spiritual and emotional reserves, but it didn’t land the final punch. That came from other cultural disrupters—some recent, some decades old—disordering their relationships with churchgoers. When those things manifested in ugly, brutal ways, many pastors no longer had the fortitude to withstand them.

The most widely used measure of burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory, developed by Christina Maslach and Susan E. Jackson. It measures three factors: emotional exhaustion, cynicism or depersonalization, and self-perception of professional efficacy.

Most people associate burnout with only exhaustion, but according to Rivers, “Individuals are different. Some people can have high emotional exhaustion and really high satisfaction in ministry. They’re tired but not burned out.” So burnout is a greater threat for weary pastors who also have heightened cynicism and low professional efficacy.

What sorts of things are likely to raise pastors’ cynicism and lower their job satisfaction? Barna identified “lack of commitment among laypeople” as the frustration most pastors considered the worst (35%). “People’s apathy and lack of commitment” also topped the list in a Lifeway Research study asking pastors about the greatest needs they face.

The digitization of church services, sped along by the pandemic, has twisted the knife in that regard. Local pastors have bemoaned people’s preference for disembodied sermons since Paul Rader first preached the gospel message from a makeshift radio station on the roof of Chicago’s City Hall in 1922.

But since the pandemic, the debate over in-person versus impersonal preaching has been complicated considerably. For the first time, due to the recent proliferation of livestreamed and recorded services, local pastors are in stiff competition with obscure preachers from other states.

Glenn Packiam, associate senior pastor at New Life Church in Colorado Springs and author of The Resilient Pastor, told the story of a churchgoer who confronted him about his face mask.

“He told me about another pastor in Texas whose sermon he just listened to about how this is all a government attempt to create a fake crisis so they can increase their control,” Packiam said. “He’s listening to a pastor who doesn’t know his name and didn’t baptize his kids, and he’s using that YouTube sermon to rebuke me, a pastor in his own church.”

Even as mask mandates have subsided in the United States, pastors will remember the chaos they sowed for years to come. Some have joked that masks became the new carpet-color argument for churches.

But Packiam feels the divisions they caused may be more historic. “Mask-wearing is the latest iteration of our pseudo-religious culture,” he said. “One hundred years ago, the divide was between mainline and evangelicals, and you had the whole Social Gospel thing. If you were pro-evangelism, then you were a conservative church, and if you were all about feeding the hungry, then you must be liberal. The latest iteration of that is ‘If you’re pro-mask, then you must also be liberal in your politics and likely in your theology; and if you’re anti-mask, then you’re definitely conservative in your politics and theology.’”

The underlying issue causing pastors so much angst right now isn’t the existence of streaming technology or a particular mask policy. It’s lack of congregational trust. “There’s a sobering reality that we’re not living in the day when people would say, ‘My pastor said we need to wear a mask to protect the vulnerable, so we’ll do it.’ It’s just not like that anymore,” Packiam said.

The recent proliferation of high-profile ministry scandals hasn’t helped things, but Americans’ confidence in clergy has been falling for some time. Gallup asks people every year about their level of trust in various professions. In 2012, more than half of respondents ranked clergy “high” or “very high” in honesty and ethics. In 2018, that number dropped to a little over a third.

More concerning in 2018 was that, even among American Christians—the very people who pay pastors’ salaries—only 42 percent had a high level of trust in clergy.

In other words, do people trust their local pastor to have their best interests in mind, to do their theological and biblical homework, and to shepherd them well even if they disagree on a social issue or two?

The answer, increasingly, is no.

And as trust in pastors wanes, the amount of criticism they receive from churchgoers is increasing, Nemecek says. “When I first started in ministry in the early 2000s, it might be two or three days after you preached a sermon that somebody would come to you [with critical feedback]—maybe even a couple of weeks. Now it’s seconds. You may receive a text the same day or even while you’re preaching.”

Packiam worries we’ve missed the forest for the trees when it comes to ministry health.

“The greater need is not to say, ‘Oh gosh, we need to raise up new pastors to fill in all these gaps that are being created.’ The need is to strengthen and help pastors become resilient.” What can churches do to help pastors build spiritual fortitude and to support them during times of crisis?

It stands to reason that churchgoers looking to support pastors right now should simply increase the amount of affirmation they give to balance out the discouraging conversations. And they should. But 90 percent of pastors already say that their family regularly receives genuine encouragement from the church, according to Lifeway Research. While affirmation hums, criticism screeches.

“Let’s be consistent stars; let’s stay in the sky for a bit longer.” Glenn Packiam

According to Nemecek, “One pastor I was talking with several months ago was really discouraged about what’s going on and was thinking of quitting. I said, ‘Tell me, what are some good things that have happened recently?’ He thought for a second and said, ‘Oh, I baptized 30 people last week.’ That’s huge! He had such a hard week of so much intense criticism that he couldn’t even remember the positive stuff that happened earlier.”

A pat on the back or a “Good sermon, Pastor!” won’t be enough to match the crisis many pastors are facing.

When Jonathan Dodson experienced his sudden-onset ministry burnout, he went straight to his elders and explained the situation to them.

“They said, ‘Let’s just sit in the dirt with you. Let’s mourn. We know it’s been an atrocious two years,’” he said.

Dodson was as surprised as most pastors might be by such a response. More often, they fear the kind of encounter he heard about a short time later. “I was meeting with a group of pastors who I have lunch with every six weeks, and I told them the story of this sitting in the dirt together. And the wisest and oldest pastor in the room said, ‘I can’t believe they responded like that. My elders would have tried to fix me.’”

Our first instincts, when we see a church leader spiraling, might be to jump to their rescue with book suggestions or time management recommendations. But ailing pastors need something deeper.

“We’re in a fix-it culture,” Dodson said. “If there’s something broken, we think, How do we get it healthy? How do we get it back on track? The category of lament is very inefficient. It’s unproductive.”

Dodson’s leadership team knew the greatest need of the moment wasn’t to get him back to preaching ASAP. His wounds were deep, and he needed time to heal. So they granted him an immediate sabbatical. No agenda. No strings attached. Just a promise of some time to process the previous two years without the weight of congregational leadership resting on his shoulders.

“The first few weeks were weeks of lament, of spontaneous crying, having to pull over because the tears were just coming so fast and hard. Not being able to walk into church. Feeling paralyzed and having to sit in the parking lot for 30 minutes and then sneak in the back,” he said.

“Then I moved into a second phase. I got away to the Colorado Rockies. Natural beauty is healing and restorative for me. I had some days of silence and solitude, and it was just so wonderful.”

Dodson found respite in Isaiah 53 and Lamentations. “In Lamentations 3, there’s a long argument that basically talks about the wormwood and the bitterness of [Jeremiah’s] sufferings. It only gets into that bit we’re familiar with about mercies being new every morning after [more than] 10 verses of suffering. But after that, he says, ‘It is good.’ The Lord does good to those who wait for him; the Lord is good to those who sit quietly and wait.”

This message and time with the Lord were just what Dodson needed. “It was in that quiet and waiting that restoration began to happen, where I wasn’t responsible for people, and the grief began to slip away.”

If there’s a silver lining in all of this, it is that recent years have placed an accent mark over pastors’ need to prioritize sustainability over tenacity.

“When I was first starting out in ministry,” Nemecek said, “some of the older pastors who mentored me had been taught things like if they took care of the church, God would take care of their family. And my generation saw that disintegrate and these pastors suffering from broken families and difficulties because of that lack of self-care.”

Packiam shared a similar story. “There are several retired pastors in my congregation who have said to me, ‘Back in my day, you had better preach 50 or 52 Sundays out of the year, and if you didn’t, people would wonder what the matter was; where did you go?’ ” he said. “I grew up on the radical missionary stories of people who moved overseas and left their families and were shooting stars—they burned out quickly. We’ve moved from that paradigm to say, ‘Let’s be consistent stars; let’s stay in the sky for a bit longer.’”

This trend toward sustainability is showing up in the data. In an article reflecting on the 2021 Lifeway Research study, Scott McConnell wrote, “Fewer pastors agree they must be ‘on-call’ 24 hours a day, declining from 84% to 71%. Perhaps even more telling, the majority of pastors (51%) strongly agreed with this expectation in 2015, while only a third (34%) strongly feel this obligation today.”

Pastors have no special well of spiritual strength to draw from, no secret tools to reinforce their spiritual fortitude beyond what any of us has. It’s easy to forget that Christ’s undershepherds are still sheep in his flock. If we treat pastors like spiritual superheroes, we do them a disservice. Superman doesn’t need to do pushups, but ministers still need permission and margin to do their spiritual exercises: time alone with God, time praying, time in Scripture beyond sermon prep, time with spiritual directors and counselors and other pastors who get what they’re going through.

Will pastors end up joining the Great Resignation? The answer may be up to us. Ward believes the pandemic “exposed a gap between clergy and laity as to who is carrying the load as far as pastoral care and leadership, not just leading programs.”

Her dream is to see pastors stop shouldering all the church’s weight alone. After all, an equipped and commissioned church laity has a better chance of not only retaining their pastor but also carrying on in strength if the pastor leaves. “How can laity pick up that load of caring and ministering? Hopefully we will see an increase in every-member ministry,” she said.

As a closing thought, Dodson added one more thing pastors need right now from the people in their churches: “invitations to nonthreatening lunches.”

He shared about the time leading up to his burnout experience. “I was shell-shocked, so when I got invitations to lunch, I started asking immediately, ‘Is this an emergency? Is there something I need to know about?’ I don’t think people realize how many of those meetings their pastors are having. If you’re a thoughtful church member, take your pastor to lunch or coffee and let them know, ‘I just want to encourage you and express my gratitude for you.’ That would mean a lot to pastors.”

Kyle Rohane is an acquisitions editor at Zondervan Reflective in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Before that, he was CT Pastors editor at Christianity Today.