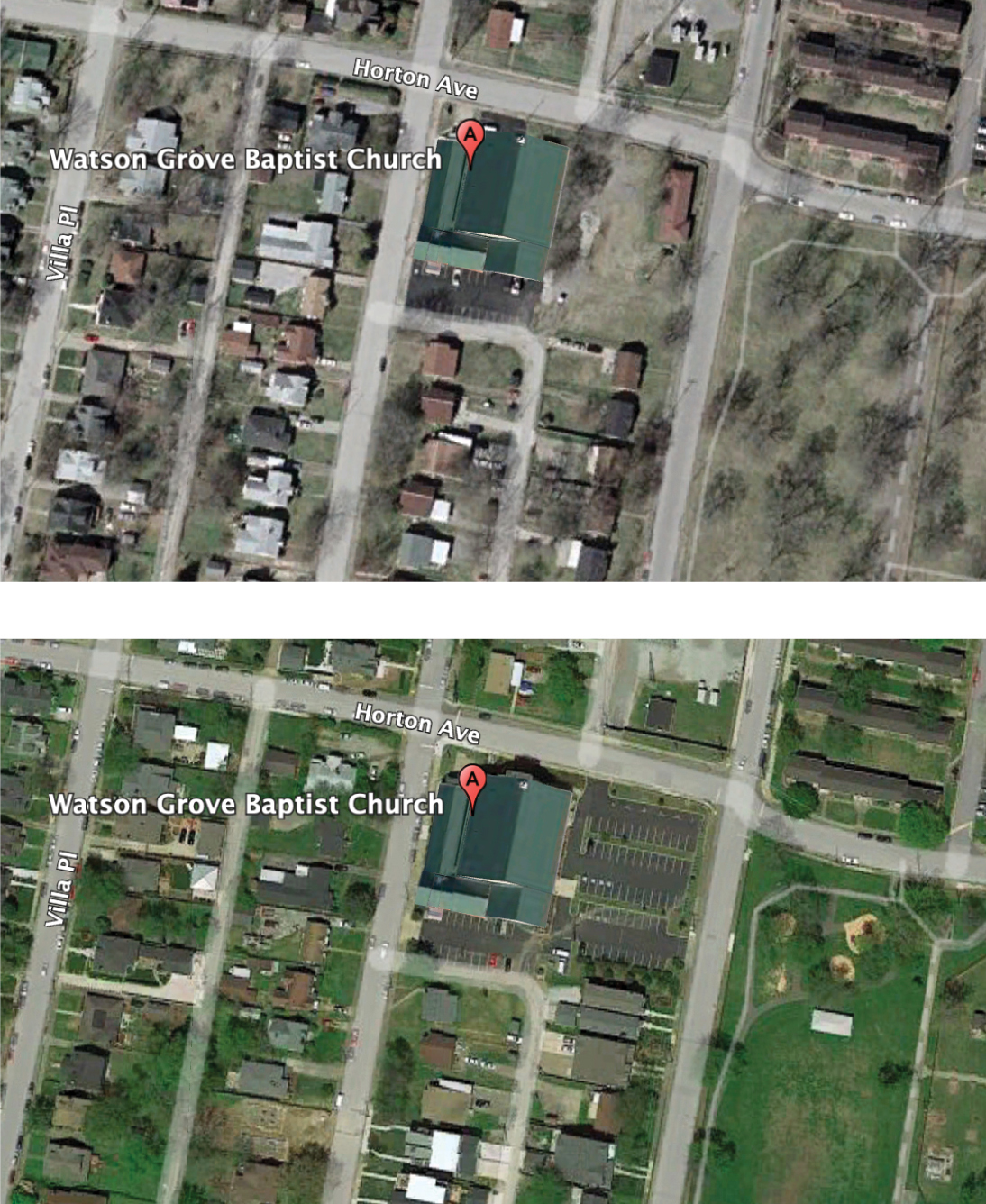

To understand what’s happening at Watson Grove Baptist Church, you have to understand its parking lot.

The modest patch of blacktop near downtown Nashville holds 100 cars. It’s framed by a manicured lawn and colorful shrubs and wraps around a group of connected redbrick buildings that has expanded with the congregation over the years.

Watson Grove sits on the corner of 14th and Horton streets in a place called Edgehill, a rapidly developing neighborhood bordered by Music Row to the north and 12 South, one of Nashville’s trendiest neighborhoods, to the south. Edgehill contains both public housing and a commercial district with a lively nightlife and lifestyle-brand stores like Warby Parker.

The church’s parking lot, in some ways, encapsulates the evolving story of the traditionally working- and middle-class African American community around it. It tells of Edgehill’s increasing urban bustle (the church installed speed bumps in the lot as more drivers were cutting through and endangering children crossing it to board the school bus) and of the neighborhood’s struggles with crime (police cars monitor the neighborhood from the parking lot, which hosted a hearse after a teenage girl from the community was killed in a drive-by shooting).

The blacktop also tells of gentrification, of supply and demand. Like Edgehill itself, where home prices have soared in recent years, there is not enough parking lot to go around.

A historically Black congregation, Watson Grove has grown over the past decade from around 300 people to more than 3,000 over two campuses just before the pandemic halted in-person services. Its modern sanctuary seats 750 people. And it became a multisite church in 2019, when it opened its second location in suburban Franklin, Tennessee.

Google Earth

Google EarthBut at the Edgehill campus, the influx of new worshipers has not come from surrounding homes and apartments. Most church members have either moved out of Edgehill or have never lived there.

Because there was so little space to put all those commuters’ vehicles, the church increased to four services. Cars spilled out onto the surrounding streets, into the library parking lot around the corner, and into a parking lot offered by a nonprofit a quarter mile away.

“I believe we grew in spite of gentrification” rather than because of it, said John Faison Sr., who pastors the 133-year-old congregation known as “The Grove.”

But some of The Grove’s neighbors, especially new neighbors, haven’t been excited about that growth. They’ve pushed for resident parking permits, which would prevent commuters from parking on the street. So far the church has persuaded the neighborhood association not to go that route.

“We tried to be neighborly,” Faison said. “We shouldn’t be blocking your driveway. However, you shouldn’t be cursing out Black people who are parking in front of your house.”

Courtesy of The Grove

Courtesy of The GroveThe Grove’s parking woes are a symptom of a larger phenomenon that might be called “spiritual gentrification.” As neighborhoods change, church communities are often forced to reevaluate their identity, asking hard questions: If the people of a church move elsewhere, should the building and pastors follow? How different can a neighborhood become before it’s no longer the neighborhood a church is called to serve?

In other words, who is a church for?

“It makes a church reexamine its call. Every single church is called to make disciples,” Alvin Sanders, a former church planter and president of the nonprofit World Impact, told The Tennessean in 2017. “It has to decide is it there to reach its community even if its community changes? That’s really the biggest pressure.”

Gentrification, a term invented by British sociologist Ruth Glass, is commonly understood as the process of wealthier—often white—people buying and developing property in urban neighborhoods, displacing lower-income residents who can no longer afford to live in the area.

Thanks to troves of census and real estate data, the trend has been heavily studied in recent years. Unsurprisingly, gentrification is complex. When property values in a neighborhood rise, working-class residents sometimes leave and sometimes do not. They may be forced out by unaffordable rent, or they may reap a windfall by selling a home that is suddenly worth a lot. “Gentrifiers” may be higher-income white residents, or, especially in major cities, they may also be higher-income Black and Latino residents.

Often overlooked in studies, however, is faith. A significant impact of gentrification is secularization, sociologist Orvic Pada argued in Biola’s Justice, Spirituality & Education Journal. “Religious organizations are forced to move out of the area, cease to operate due to rising property values, or reconfigure their identity, methods, and approach to cater to a different demographic group,” he wrote.

Churches that provide social services can help “slow down the effects” of gentrification by preventing lower-income residents from being pushed out, according to David Kresta, a researcher with Duke Divinity School. However, Pada observes, “gentrified” church outreach is often simultaneously targeting the wealthier creative class in changing communities—for instance, running cafés, restaurants, and other forms of social-entrepreneurship-as-ministry.

In the 1950s, The Grove’s Edgehill neighborhood was a popular area for African Americans, including many Black doctors, professors, and business owners, Faison said on the Vanderbloemen Leadership Podcast last year. The church building was built by a local Black-owned construction company. But times changed. There was redlining—where banks withheld loans from homebuyers in low-income areas—and white flight. Interstate 65 cut through the neighborhood. The church watched crime rise and education plummet. Public housing was put in.

In contexts like these, Faison said, the Black church was a place where Black people found affirmation, identity, and were “celebrated in a community that saw your inherent value” during a time of segregation and Jim Crow laws. “You’d show up to Black church and, while you were called racial epithets throughout the week, at church you were Deacon Jones.”

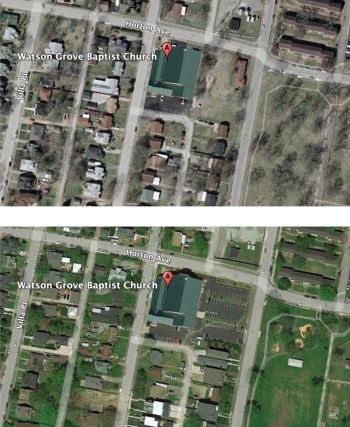

Top: Nashville Public Library Metro Archives / Bottom: Google Maps

Top: Nashville Public Library Metro Archives / Bottom: Google MapsGentrification has torn at that sense of cohesion in Edgehill. It “impacts our church in manifold ways,” Faison said. “First of all, many of our members can no longer afford to live in the neighborhood and the area they were living … so they have to leave and go to different places. Well, that now separates them from the center of the Black community: the Black church.”

Pastoring an increasingly commuter church, Faison observed his congregants have a harder time attending in-person Bible studies and students have a harder time making it to youth group.

Churches change when their members move out of a neighborhood or to a city’s outskirts. Some churches die: Countless empty urban church buildings, abandoned for myriad reasons by Catholics and Episcopalians and Methodists and Baptists, have been turned into bars and houses and luxury apartment buildings.

Other congregations decide that, to stay faithful to their call, they must abandon their original neighborhood and follow their members.

When Aaron and Michelle Reyes planted a church in Austin, Texas, in 2014 with a core group of 10, they were passionate about reaching the area where Aaron had grown up and creating a church centered on Black and brown communities. Most of their congregants were Latinos and blue-collar families. The East Austin church slowly became multiethnic as other families joined, and now about half of the more than 200 congregants are Latino, joined by white, Asian, and African American families.

In those early years, however, they quickly realized they had a problem. Marketing themselves as a “new” church was not attracting the people they had intended to reach in the changing neighborhood.

“We realized ‘new’ isn’t going to communicate what we want to express,” Aaron Reyes said. It instead communicated concepts like higher taxes and displacement. It sounded more like the coffee roaster down the road and less like a community. “So we started calling ourselves a ‘young’ church.” They also changed their name, from Church of the Violet Crown, which was being used by a lot of gentrifying businesses, to Hope Community Church.

Still, they noticed more of their folks being pushed out of the neighborhood. It was difficult and expensive for many attendees to get to church via public transportation. “As folks were moving, we just knew we had to leave,” he added. They found a building farther northeast, in Austin’s Windsor Park neighborhood.

But not all churches go. Many choose to stay. Life Change Church in Northeast Portland, Oregon—a neighborhood known to many as “the Hood”—relocated in the 1990s from a small A-frame on a cul-de-sac where it started in the 1960s to an old shopping complex. Now, according to pastor Mark Strong, the building is “dwarfed by several new developments.”

Courtesy of Life Change Church

Courtesy of Life Change ChurchIn his recent book, Who Moved My Neighborhood?: Leading Congregations Through Gentrification and Economic Change, Strong recounts reading an article about the top 10 “hippest” cities in the US and being surprised to find that Portland was No. 1. And the accompanying photo showed his church’s neighborhood. “Wow,” he thought. “What was once the Hood is now a national Hipsterville!”

His congregation realized that neighborhood change was taking place when they found themselves asking questions such as “What happened to this or that business?” and “Where is this family or that family?”

Strong realized that the problem his congregation faced “wasn’t so much these changes were occurring but that our community was not being included in this new neighborhood narrative,” whether from ignorance of how to seek change or from being exhausted trying to do so.

Strong offers seven steps for how he thinks churches should navigate the often-painful shifts of gentrification and remain resilient: Remember the old neighborhood, recognize the neighborhood shifts, realize the moved neighborhood, reconstruct your moved neighborhood, allow yourself rage, reconcile with the idea, and finally, revamp your church in the new neighborhood.

“Sure, it would be nice if God miraculously healed our pain and immediately restored what has been removed,” Strong writes. “However, he chooses to walk us through the valley and not transport us out of it.”

But generally, his call to churches undergoing similar changes is to stay. “Your neighborhood needs your church. And your church has the potential to be the best neighbor that the people in your neighborhood will ever have,” he writes.

Darryl Williamson and his 150-person church have chosen similarly. The lead pastor of Living Faith Bible Fellowship in Tampa, Florida, could only think of one family, in addition to his, that hadn’t moved in the past decade. He prefers the term “spiritual exodus” to describe their experience.

But like The Grove, instead of relocating with its congregation, Living Faith became more of a commuter church and saw its demographics shift with the changing neighborhood.

Courtesy of Life Change Church

Courtesy of Life Change ChurchWilliamson, who is also a board member at The Gospel Coalition, is careful with the language he uses to describe neighborhood gentrification. Many historically African American churches like his are not populated by people originally from the neighborhood, he said.

After talking to other Black pastors who have ministered for four decades and watching wealthy Black families relocate out of the cities, Williamson is not convinced gentrification “is quite being ‘done’ to us.” Even as someone who admits he left his hometown of Nashville, he pushes against an escapist mindset.

Rather, Williamson is passionate that his church be rooted in its geographical location. “I don’t know that we have discipled people to have responsibility for their neighborhood,” he said. “There are multiple Black communities that have experienced gentrification where what was needed was a greater conversation about how to lead and not just to personally aspire.”

While gentrification tends to secularize a neighborhood, it does, of course, often bring in new churches pastored by outsiders. And just as new neighbors can bring new conflicts, so can startup churches.

“If you’ve been in the neighborhood for 20 years trying to care for a congregation, and Planter A comes in and doesn’t greet you or anything and sets up shop down the road, it is an affront and grievous,” said Thabiti Anyabwile, who founded the Crete Collective, a church planting network that focuses on Black and brown neighborhoods.

“Folks that are planting communities that are in transition are often overlooking churches that already exist,” he said. “And, less politely, they are charging that these churches are less faithful to the gospel. Instead of being a revitalizing force, they are displacing in some cases decades-long or century-long presence.”

All of these pastors have grappled with the question of identity—Who are the people in my church? To whom does the local body belong?

In fact, Anyabwile believes the majority of new multiethnic church plants are not actually in the poorest areas of a city. They are “hood adjacent,” as he refers to it. His view is consistent with research on gentrification showing that gentrifiers tend not to move into very Black or very poor neighborhoods unless, say, the neighborhood is right next to a central business district.

On the other hand, researchers like Duke’s David Kresta have found that white churches in nonwhite neighborhoods can signal as a “beacon or an amenity” for new residents and contribute to further gentrification.

Among others, the Acts 29 church planting network has recognized this problem and recently launched a cohort called Church in Hard Places, sending or supporting a diverse group of pastors in poor neighborhoods—both rural and urban.

“The leadership reassessed that church planting was doing really well in upper-middle-class affluent neighborhoods—reaching white people, basically,” said Tyler St. Clair, a network leader and pastor of a church plant in Detroit. “But we had no traction in poor white and poor Black [communities] all around the world.” Their urban track equips city church leaders specifically to deal with gentrification and poverty.

After watching new church planters “parachute” into neighborhoods and draw people from the suburbs rather than their city block, St. Clair coaches new pastors to plant their lives in a community and learn as missionaries, not saviors. “You should receive the compliment ‘I see you everywhere,’ ” he says. “I don’t just sleep here.”

Courtesy of The Grove

Courtesy of The GroveFaison has observed this tension between his historically Black church and the white church planters that come to his Nashville neighborhood. In the past decade, he says, only one of the 12 churches that were planted near him has survived.

“Their motives will be tested by their willingness to be part of that community,” he said. Instead of connecting with existing neighborhood churches, he thinks, many church plants see them as theologically or ecclesiologically inferior, or as competition. “It’s not even evangelical; it’s economic. It’s seen in how they relate to the community. Their goal is to build a kingdom that’s theirs and like them,” he said.

But Williamson sees the flip side. He sees gentrification as an opportunity for legacy Black and brown churches to “grab the reins” of the multicultural conversation and lead the way, rather than being on the defensive and waiting for majority-white churches to debate the need for racial reconciliation.

He believes Black and brown churches can pursue multiethnicity and attract white brothers and sisters who are allies. “What does that mean for the next generation?” he said. “Who are we in 30 years if there is a mass migration of white brothers and sisters out of white megachurches to Black and brown churches around the city to be led and be discipled and lead and be disciplers?”

He’s not alone. Only one-third of Black Americans think historically Black congregations “should preserve their traditional racial character,” according to a 2021 Pew study. And 61 percent of Black Americans say that historically Black congregations “should become more racially and ethnically diverse,” whether they attend majority-Black churches or not.

And in Portland, while Mark Strong’s church ministers in a gentrifying African American neighborhood, he argues that the “issue of moved neighborhoods is not exclusively a Black neighborhood problem.” All kinds of neighborhoods change, and Jesus is concerned equally about them, writes Strong.

All of these pastors have grappled with the question of identity—Who are the people in my church? To whom does the local body belong?—alongside questions of geography and space. Whether they realize it or not, they have wrestled with a theology of place.

“We don’t want to be a commuter church, we want to be a community church.” John Faison

David Leong, a missiologist at Seattle Pacific University, has been studying this concept for two decades. He says a theology of place starts with a recognition that to be human is to be placed. “Embodiment requires space,” he said in an interview with CT. But it’s not just about the biological reality that we are taking up space and sucking up air. Place demands that we ask, “What does it mean to live in this world?”

Scripture refers to Jesus as being “of Nazareth,” Leong writes in his book Race and Place, signaling that he “came from, and was shaped by, a particular place and the local communities found there” that “defined Jesus’ life and ministry.”

Ultimately, while Leong feels an understanding of place is vital to effective ministry, churches can still flourish even if they’re navigating gentrification imperfectly. “When we look at Jesus’ ministry and, after Pentecost, the ministry of the Holy Spirit, we find that the human boundaries we’ve constructed don’t seem to interfere with God’s work in particular places,” he told CT in 2017.

Aaron Reyes, for one, doesn’t think “theology of place” is the right way to approach the issue of gentrification and understanding church community.

“It’s a theology of people rather than a theology of place,” he said. In the New Testament, he pointed out, churches were described by a group of people rather than an address. The location could be anywhere, in any person’s house (as in Acts 16:40).

Both Leong and Faison say pastors need to figure out their church’s calling. Leong tells churches to be “really intentional” about the decision to stay and commit to a neighborhood even if there is pressure to leave. Those who do stay must be aware of and hospitable toward folks who are being displaced, he said.

“Churches can struggle to turn their direction outward,” Leong said.

Faison also advises pastors, “You have to wrestle with Are you called to this area? Are you called to this space? And for every church it’s a different answer. Maybe I’m called to those people that I serve, but I’m not called to this space.”

For Watson Grove, the answer is clear. Faison says their calling is to be a Black church and not a multicultural one. And yet their calling is not to follow their people out of the city. It’s to minister to their surrounding community.

“We have to adapt to what this community looks like. I cannot be stuck in remembrance only and wanting it to be what it used to be. It just ain’t,” he said. “Our calling is to be a community church. That’s who we’ve been since 1889. We don’t want to be a commuter church, we want to be a community church.”

Kara Bettis is an associate editor at Christianity Today.