As someone who studies religion and politics, I often find myself in “fun” conversations at the Thanksgiving table. As the turkey’s carved, the stuffing passed, and the pies put out to cool, my aunts or cousins or their plus ones will ask me to agree that America is in decline. It used to be, they will say, that this was a Christian nation, but now the government isn’t doing what it needs to do to defend our values.

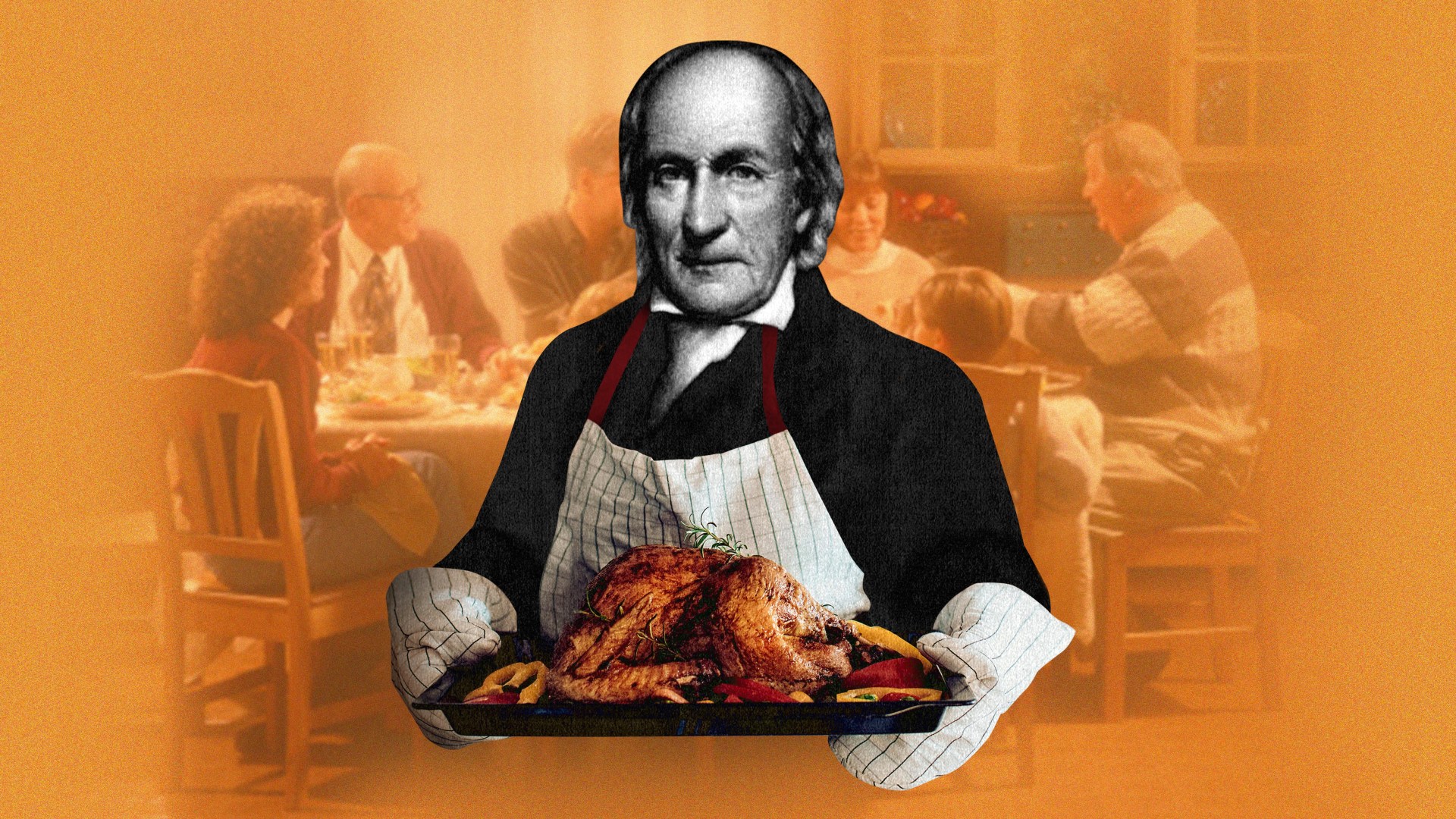

As they nostalgically recall a golden age when America was a Christian nation, I am reminded of an eccentric Baptist minister with a 1,200-pound wheel of cheese who offered an alternative vision of confident religious conviction in the public square—confident enough that it didn’t need government support.

Maybe it’s not fair to call John Leland, a Revolutionary-era Baptist minister, eccentric. But he did once give President Thomas Jefferson a four-foot, four-and-a-half-inch wheel of cheese made from the milk of 900 cows. The author of the Declaration of Independence called it “an ebullition of the passion of republicanism.”

So, he was at least a little eccentric.

More important to me is that Leland spent his life articulating a vision of Christian confidence. He was a passionate advocate for religious freedom, arguing the truth needs no support from the government and doesn’t depend on social privilege.

Congregationalists and Anglicans at the time appealed to the state’s authority to uphold religious doctrine. They believed that an ordered society could not stand the jostle of diverse religious beliefs and that the truth needed protection from the government. Leland, along with other Baptists and evangelicals at the time, rejected this. He said only error needed support; the truth could flourish without the assistance of laws and law enforcement.

His argument for religious liberty is a model for Christians engaging culture because it recognizes both the inviolability of conscience and the inability of falsehood to stand in the face of truth. He shows us how to hold to the truth of the gospel with confidence, in a spirit that opposes fearmongering over a declining Christian culture.

At the core of Leland’s approach to religious liberty is a bedrock assumption that the conscience is inviolable. Leland is not alone in this sentiment among historic Baptists. In 1612, Thomas Helwys, an early English Baptist, argued for religious liberty for “heretics, Turks, Jews, or whatsoever.” In 1644, Roger Williams equated the violation of conscience by the Parliament of England with the violation of the body. But it is clearest in the words of John Leland who plainly stated, in his aptly named 1791 sermon “The Rights of Conscience Inalienable,” that the government has no right to interfere with the religious beliefs of its citizens.

“If government can answer for individuals at the day of judgment, let men be controlled by it in religious matters,” he wrote. “Otherwise, let men be free.”

This is not to say that the conscience is perfect. Leland, as a believer in the sinfulness of humanity, believed that the internal compass could err. But if it was to err, it should be because the individual freely chose it, not because of an outside compulsion such as the threat of punishment or the enticement of honors.

So strongly did he believe in this maxim of the relationship between the government and religion that he was willing to scuttle the United States Constitution when it was sent to Virginia for ratification. He and other members of the Baptist General Committee considered voting it down unless there was a guarantee of an amendment to secure religious liberty. This was noticed by James Madison, who was warned in several letters that the Baptists were against the proposal, especially John Leland, “the leader of the Virginia Baptists.” Only after Leland secured promises from Madison (in a meeting that has assumed legendary status) that an amendment to the Constitution securing the rights of conscience would be proposed did Baptists mobilize in support of the Constitution.

In his defense of conscience, Leland understood what should be increasingly clear to modern Christians: The privileges of the state do not lead to true converts. Rather, privileges encourage Christians to be nominal—more concerned with cultural favor than faithfulness.

This is becoming increasingly clear in contemporary America as those privileges are taken away, a point my family members rightly recognize in their holiday questions. Church membership has dropped below 50 percent for the first time since Gallup started asking the question. The religiously unaffiliated—often referred to as “nones”—are one of the fastest-growing and largest groups in America. Granted, there are many reasons for this, not the least of which is a devaluing of institutions in all areas of American life and rejection of the abuses and harms that have been revealed inside and perpetrated by the church. But where previous generations were more likely to at least identify as Christian to benefit from the social advantages of association with a church, that is changing.

But the changing landscape reveals the joy of Leland’s method for engagement. The truth does not need the protection of the government; it needs only a vocal and committed proponent. In this moment of history, each person must live convinced of his or her own position, and we are required only to hold it with humility. There must be a freedom to disagree, even vigorously. But at the end of the day, our minds should always be open to conviction, and each of us should be convinced of what we believe because we believe it to be true.

Christians used to be able to rely on governmental or even just cultural support for their positions. Now, with a crumbling Bible Belt and secularizing public square, that is no longer the case. But “it is error, and error alone, that needs human support,” according to Leland. Those who need the support of the government for their position reveal their underlying belief that something in their position cannot stand up to the light of scrutiny.

It is not because the truth is weak that Christians turn to cultural support. It is because Christians are unconvinced of their own positions. Leland calls for us not to protect the truth but to actually believe it and to confidently assert it in the public square, just as he did regularly in Virginia and New England.

And though Leland was a strict separationist (he even argued against Sabbath laws), he did not want the public square to be naked of religious claims, which, as public theologian Richard John Neuhaus has argued, is impossible. Leland just wanted neutrality. The same man who argued against state sponsorship of religion also preached to Congress in 1801. This requires a confidence on the part of Christians who do not bemoan declining acceptance of their beliefs but who boldly and prophetically declare to the world the truths of the kingdom of God and the rule of Christ over all areas of life—political, spiritual, sexual, economic, racial, and personal.

It also requires humility from Christians because we recognize that today’s atheist may be our future brother or sister. Christianity is not transmitted genetically but rather through the renewing of hearts and minds (Rom. 12:1–2). As CT’s public theologian Russell Moore has written, the next Billy Graham is likely not currently a believer. So, we do not enter the public square seeking to protect ourselves or to overthrow our enemies. Rather, like Leland, we seek the freedom to proclaim the truth and allow it to work in the minds and spirits of those who are listening. And Leland’s context for convictional engagement, the Second Great Awakening, should offer hope and optimism to those who worry about the state of religion in America.

Leland’s optimism about the power of reason and truth appears naïve in our age of outrage, sound bites, and fake news echo chambers. However, for the Christian, his method is incredibly useful. It recognizes that our interlocutors are not enemies even if they are ideological opponents. They are, at worst, deluded by a lie and thus need to be confronted with the truth with confidence and humility.

The tension between those two is one that we could all recover in an age of hot takes and attempts to score points for our tribes. It will take a confidence in the power of our arguments rather than the number in our voting bloc. It will take a humility able to admit error or be proven wrong rather than a bombastic spirit seeking to score points in the latest Twitter sparring match.

The same day Leland delivered that wheel of cheese to Jefferson, Jefferson wrote his famed letter to the Danbury Baptists declaring a “wall of separation” between government and religion. Leland supported this separation, even if he disagreed with Jefferson about what that looked like practically. Leland saw in America neither an embattled Zion nor a Babylonian exile but rather an Athenian hill asking for debate (Acts 17:16–34).

So, when we’re eating some pumpkin pie and listening to a cousin’s husband talk about the outrage du jour, maybe we can be more like Leland. Instead of wringing our hands about the threats of the future and bemoaning our inability to live in the past, we can follow the example of that eccentric Baptist and go about the work of proclaiming the truth and defending each individual’s right to live in accordance with the convictions of his or her conscience.

Alex Ward serves as the lead researcher for the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.