This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

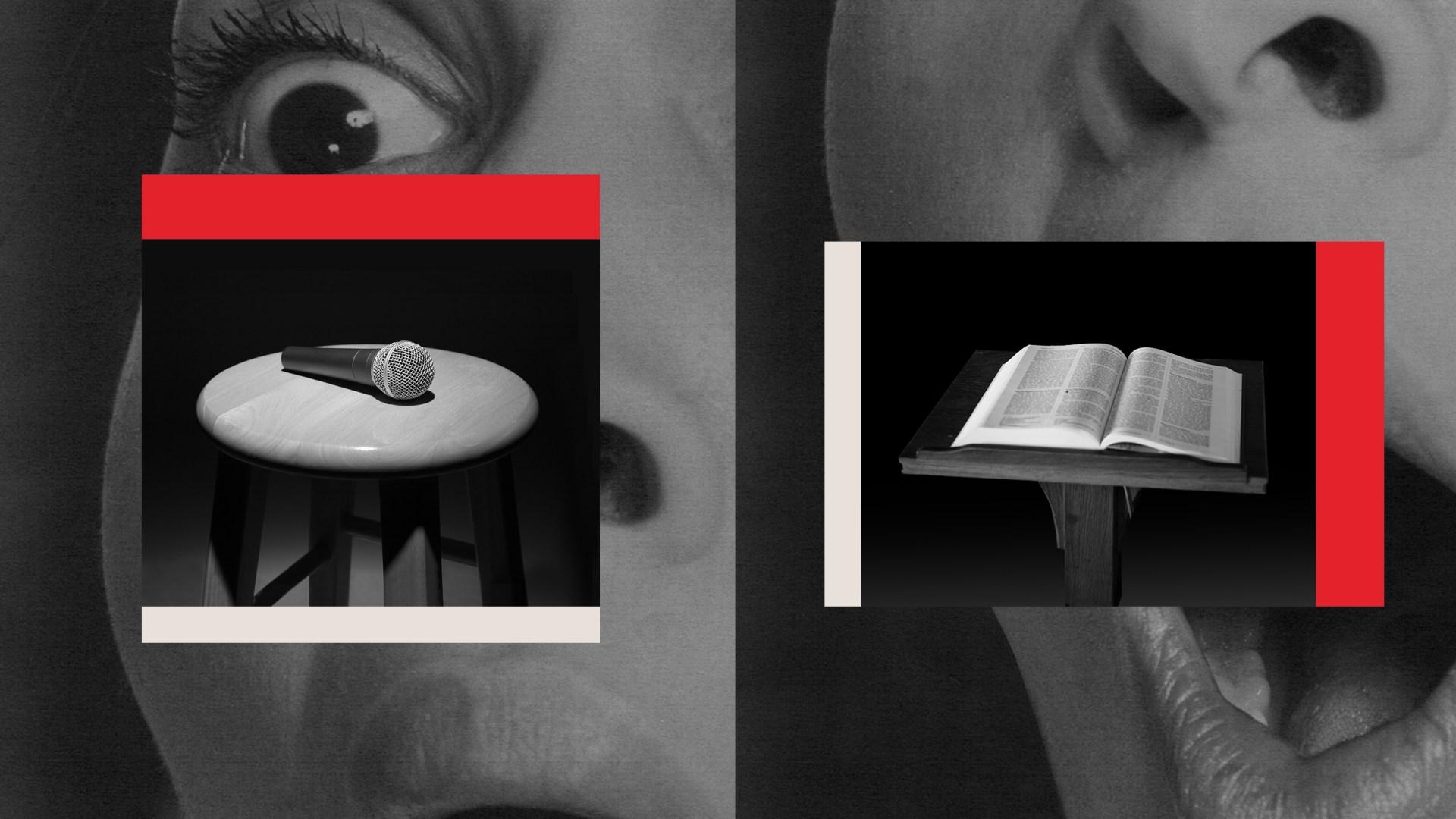

Apparently, comedian Dave Chappelle isn’t welcome at his own high school. According to news reports, the Duke Ellington School of the Arts delayed a ceremony to celebrate the renaming of its theater after the famous alum because students threatened to walk out.

Netflix fielded similar threats from its employees after Chappelle’s controversial standup comedy special aired on the streaming service. Many felt it was insulting toward transgender people and others. Chappelle’s special has since prompted a thousand debates about political correctness, cancel culture, and the nature of respect and civility in the public square.

While those debates are important, let’s set them aside for a moment and reflect instead on the question of who was laughing—and why.

As the Chappelle controversy has unfolded, I have found myself in conversations with two specific people on opposite sides of the “love him or hate him” spectrum. Both of these individuals were surprised by their mixed feelings—not about the social commentary or the rhetoric of the comedian but by their own reactions and responses.

One of them is a staunch conservative who’s been concerned about our country entering a “What are your pronouns?” era. He agreed with Chappelle’s arguments on that point but said he never laughed at them. In fact, he cringed several times at the crude language in the routine. “I was with him on the issue,” he said. “It just wasn’t my kind of humor.”

The other person is a committed progressive outraged by what he sees as Chappelle taking cheap shots at a vulnerable population—and yet he had the reverse response. “I hated what he was saying, at least at those parts,” he said, before looking down and wincing. “But I have to admit, he was funny.”

So while the conservative felt obligated to laugh, he felt left out because he didn’t. And although the progressive despised what was said, he felt guilty because he did laugh.

In September, David Sims of The Atlantic profiled another controversial and politically charged comedian, Norm Macdonald, after Macdonald’s death from cancer. As with Chappelle, part of Macdonald’s legacy was that he could prompt people to “laugh and gasp in shock in equal measure.” The key to all of this, Sims argued, was not Macdonald’s place on the political spectrum, which was to the right of most of his cohort. It wasn’t even his comedic material itself, which was often rather coarse. Instead, it was Macdonald’s view of what comedy is meant to do—or, more specifically, of how laughter works.

According to Sims, Macdonald argued that standups should “hunt for laughter, not applause.” The comedian went on to explain, “There’s a difference between a clap and a laugh. A laugh is involuntary, but the crowd is in complete control when they’re clapping. They’re saying, ‘We agree with what you’re saying; proceed!’ … But when they’re laughing, they’re genuinely surprised. And when they’re not laughing, they’re really surprised. And sometimes I think, in my little head, that that’s the best comedy of all.”

This seems to have little to do with the witness of the church. After all, we’re not trying to make people laugh. But that element of surprise—an involuntary reaction that goes beyond our sets of ideologies and expectations—is actually a key part of what we are called to do, and the lack of it partially explains why we so often fail.

In the mid-20th century, theologian Reinhold Niebuhr wrote an essay on the relationship between humor and faith that was utterly humorless but nonetheless insightful. In it, Niebuhr argued that at the core of human existence is a paradox. We see ourselves as insignificant in the broad sweep of space and time, per Psalm 8: “What is mankind that you are mindful of them, human beings that you care for them?” (v. 4). But our very ability to ponder that insignificance seems to place us at the center of the universe: “You have made them a little lower than the angels” (v. 5).

A person’s melancholy “over the prospect of death,” Niebuhr wrote, is “proof of his partial transcendence over the natural process which ends in death.” Our inner and outer worlds often fail to align—and humor and faith are two different human responses to this tension.

“Laughter is our reaction to immediate incongruities and those which do not affect us essentially,” Niebuhr wrote. “Faith is the only possible response to the ultimate incongruities of existence which threaten the very meaning of our life.”

Humor, in Niebuhr’s view, is a kind of no-man’s land between cynicism and contrition. When laughter is taken to its extreme, it becomes a kind of bitterness. Think about the people you know who are hilariously fun to be around but who became that way in order to create a kind of defense mechanism—either to distract themselves from sadness or to protect themselves from potential ridicule. This is not the worst way to survive, unless one adopts the kind of sarcasm and nihilism that laughs at everything and cries at nothing.

Successful comedians—whether the skilled millionaire professionals airing on Netflix or the kids whispering jokes in the church balcony—know how to point out the incongruities of life. They recognize, as Norm Macdonald said, that laughter works best when it is least expected, when it can surprise and even startle us. Good jokes that bring genuine laughter often relate and connect to the human experience in an unpredictable way, whether it produces a reaction of “Ha! I see what you did there!” or “I can’t believe she just said that!”

Most of us have experienced times when we laughed unexpectedly—sometimes at inappropriate moments or in inappropriate contexts.

Years ago, at a funeral in Louisville, I sat next to an elderly man who was a former faculty member at the seminary where I served at the time. One of his equally elderly colleagues, whom I’ll call Harold, began walking to the front of the chapel to give a eulogy. At that very moment, my seatmate (whose hearing was basically gone) said to me in a “whisper” loud enough that everyone could hear, “Look at how bad Harold looks! Man, he has aged! Mark my words—his funeral’s next!”

All of us watched in horror as Harold turned around mid-aisle to glare in my seatmate’s direction. Then a small smile crept to the corners of Harold’s mouth as he turned back to walk to the pulpit. The more I tried to stifle my laughter—the more I said to myself, “You can’t laugh! This is a funeral!”—the harder it was for me to keep my composure.

The Christian gospel itself is not humorous. Indeed, it deals with the most serious of matters. Its ultimate aim is not laughter, but nor is it applause. The power of the gospel took the first-century Roman Empire by storm—not because it met the expectations of Rome’s cultures and subcultures but because it was perceived as thoroughly strange.

A crucified Messiah. The resurrection of the body. A church of both Jew and Gentile, slave and free. None of these fit the existing expectations and formed opinions of almost anybody in that day and age. And that’s precisely why it stood out as so different.

When it comes to Dave Chappelle, there is plenty to debate about—for instance, whether he or any other comedian is “punching down” or whether that type of comedy becomes ridicule. How far is too far before comedy ends up trespassing the bounds of civil discourse? These are important conversations. However, it’s still worth observing the way standup comedians can make the familiar surprising and the strange relatable.

Comedy can involve social commentary or political advocacy but only in a very specific way. To make us truly laugh, not just applaud, it must strike us at a surprising place—one that’s much deeper than our surface-level opinions and stances.

Laughter does not always signify joy—just as melancholy does not always equal contrition. But sometimes it’s a start.

Russell Moore leads the Public Theology Project at Christianity Today.