I can’t remember at what point I realized that I would probably go two years without a hug. Nobody knew how much worse the pandemic would get, but I knew I would be stuck in place for the duration. My friends felt a world away. Phone calls with my family had become strained. I couldn’t tell how they were really doing or articulate how I was handling the stress. (Not all that well: I had stopped showering altogether, and I was watching the Lord of the Rings movies repeatedly.)

I believe winter was approaching when the realization about huglessness hit me. Holidays loomed in the near future, and I wondered if I could deal with a Thanksgiving by myself, with horse meat instead of turkey.

I was in Central Asia. It was 2004, in the thick of the bird flu pandemic.

That period, when I was a Peace Corps volunteer, was one of my deepest experiences of loneliness. I was in a community where only one person I knew spoke English well. I could talk on a pay phone with people in the United States—through a very bad connection where I could always hear a third person breathing on the line—once every two weeks. I got sick a lot. I didn’t bathe much since the Turkish bathhouse was open to women just one day a week, during a time when I was scheduled to teach. People I didn’t know would come to my house to ask me to help them cheat on their English tests. I started talking to myself.

Some bluegrass songs, especially Emmylou Harris’s cover of “If I Needed You,” still whisk me back in time to a daybed in a little room on a steppe where Scythians’ horses had grazed, where I sat smelling like sweaty wool and writing long letters in Word XP.

And it turned out well enough. Some of my prayers for hugs were answered in the form of packages. The bird flu was brought under control. I made a local friend or two. I acquired a taste for horse and was able to celebrate holidays with my wonderfully warm, funny house church.

Loneliness is the distress someone feels when their social connections don’t meet their need for emotional intimacy. So, it’s lack. It’s disappointment. It’s something we are conscious of, even when we don’t call it loneliness. Loneliness is a thirst that drives us to seek companionship—or, perhaps better, fellowship. Without fellowship, we go on needing others and seeking relief for that need.

According to research I did in collaboration with Barna Group, one-third of US adults felt lonely at least once a day in the winter of 2020, before COVID-19 was surging in the United States. And a majority had felt lonely in the past week. About one in seven Americans indicated they felt lonely all the time.

Most people who feel lonely at least weekly say that it’s intense but not excruciating. However, of those who did feel lonely, about one in ten are suffering deeply, saying their loneliness is unbearable or one degree from unbearable.

When loneliness is chronic and miserable, it starts to chip away at a person’s quality of life and health. Loneliness gives Americans a bigger push toward early death than even obesity.

Loneliness defies our expectations in other ways, too. It’s worst among young people and least prevalent among older Americans. In the winter of 2020, almost two-thirds (64%) of boomers said they had not felt lonely in the past week. Forty-three percent of Gen Xers said the same, along with nearly one-third (32%) of millennials. The pattern of less intense loneliness for older Americans holds true not only for experiencing loneliness at all but also for its frequency and painfulness.

Loneliness and the church

Is there a cure in the church? Churchgoers experience longer life, better sleep, improved immunity, lower likelihood of heart trouble, less depression, and less stress. These sound like the mirror image of loneliness’s symptoms.

Before the data came in, I had expected to see that practicing Christians were much less lonely than other groups. Given the socializing, the singing, the opportunity for meaningful work, the average age, and the marriage rate—as well as the sense of being a significant portion of our society—I’d hypothesized that the advantage would be significant.

I had also guessed that some of those benefits against loneliness would dissipate when churches stopped meeting in order to slow the spread of COVID-19.

I was wrong on both counts. The church has a loneliness problem in more than one sense.

Despite the ways church could be expected to protect against loneliness, churchgoers were lonely about as frequently as Americans in general and slightly more often than those who didn’t go to church. In the winter of 2020, about one in six people (16%) who attend church regularly said they were lonely all the time. A majority were lonely at some point in any week.

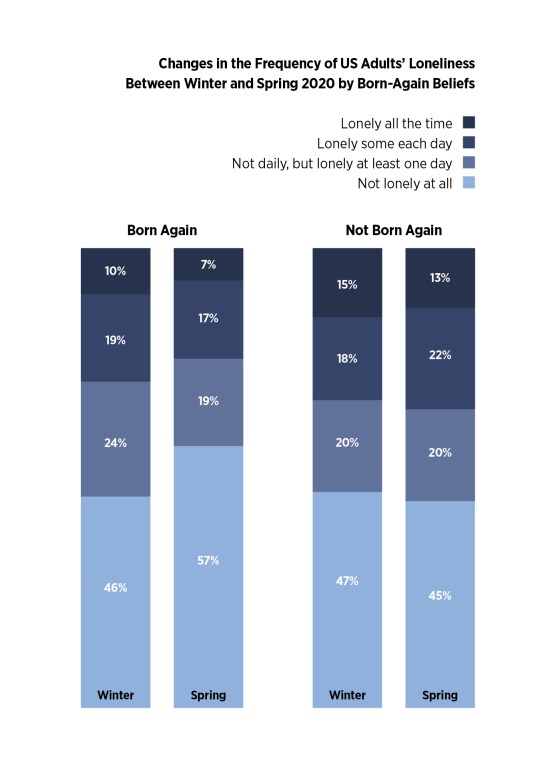

During the winter of 2020, there weren’t significant differences in the rate of loneliness between the born-again and the not-born-again groups of survey takers. But by the spring, when the COVID-19 pandemic had changed life, Christians appeared to be faring much better: Fifty-seven percent of born-again Christians said they had not felt lonely, in contrast to only 45 percent of people not born again.

In this kind of research, where we take a sort of snapshot of a situation, we don’t know some important things about loneliness. There are several possible explanations, none of which we can prove or disprove without tracking individuals over time.

What if lonely people start to come to churches at a high enough rate to keep the rate of loneliness in the church the same as the US average? Do those people who came lonely become less and less lonely as they stay? What if churches are ministering to a group of people who are especially lonely, and they are keeping those people a lot less lonely than they would be without church? Those explanations could mean that churches are a force against loneliness.

But what if people become lonely in churches and leave, driving down the average rate of loneliness in the church? What if the different rates of attendance by older and younger Americans mean that churches minister to people already unlikely to be lonely? Or perhaps, even before the pandemic, Christians were shaken, grieved, or isolated in a way nonpracticing Christians weren’t. Those explanations would mean that churches don’t protect against loneliness.

In short, it’s possible that churches, by their nature, might just be places where people experience loneliness at above- or below-average rates.

Stigma against loneliness

There is another explanation for the unexpected boost many Christians got during the pandemic. What if Christians underreported their loneliness because they wanted to be “good”?

Many people who start online searches about loneliness want quotations—and quite often Bible verses. Between 2004 and 2020, the phrase “Bible verses” was the 17th most popular term searched for in conjunction with “loneliness.” Clearly, many people interested in loneliness are also wondering what the Bible says about it, and it’s safe to assume many of them are experiencing loneliness and looking for comfort.

For better or worse, a word search in the Bible for “lonely” and “loneliness” will yield sparse results; few verses of the day are going to match the experience. Nevertheless, the Bible records a whole lot about loneliness—but it’s in the Bible’s context.

Many Christians have an idea about loneliness that goes like this: If you feel close to God (as a direct consequence of your devotional life), he will meet all your relationship needs. Wish you had more friends? You don’t need them; Jesus will be your friend. Wish you weren’t single? Jesus will be your spiritual spouse. Did someone let you down? Jesus will take the sting away.

There’s some truth to this, but I want to emphasize that God doesn’t always do these things for us when we suffer disappointment. And he certainly doesn’t do them because he is compelled by our praying a certain amount or a certain way, or because he has determined that they are “the desires of your heart” (Ps. 37:4). The expectation that we’ll get what we want if we just have the right attitude can lead to a lot of suffering and a lot of effort while trying to get God to cooperate with our agendas.

Many Christians conflate feeling bad with sin, despite knowing that Jesus was “a man of sorrows” (Isa. 53:3). Because of that, they may have put the “right” answer on the survey, indicating that they felt lonely far less than they actually did.

This may have happened in the surveys that showed similar levels of loneliness between Christians and others before the pandemic and less loneliness among some Christians during the pandemic. Churchgoing Christians do seem to have more negative views of loneliness than other religious groups do. Fifteen percent of practicing Christians said loneliness is always embarrassing, three times the rate of non-Christians (5%) and twice the rate of nonpracticing Christians (8%). A quarter of practicing Christians said loneliness is always bad, making them more likely than nonpracticing Christians and non-Christians to say so.

This embarrassment might have caused some practicing Christians to deny their loneliness. Even on anonymous surveys, many people don’t tell the truth. And if something is completely embarrassing or always bad, how likely are you to admit to it—even to yourself?

Does this mean practicing Christians are actually much lonelier than the general population? Or are their responses as accurate as other religious groups’? That we don’t know. Unfortunately, in this case, a survey cannot do more than tell us whether people think a certain answer is a better people pleaser.

Still, we should take what people say about themselves seriously. This data shows that even with the world trying to isolate people during a pandemic, practicing Christians experienced a boost, becoming less lonely than both non-Christians and nonpracticing Christians. That indicates a good deal of resilience, and maybe even some antifragility. What might be behind this, in addition to spiritual factors?

Churchgoers’ advantage

The church already does many of the things that address loneliness. Some of these are even things that doctors might be prescribing post-pandemic, like group singing (which makes people feel happier and closer), community service, being part of a community that meets in person, having confidants/confessors, and having people you can call on in an emergency.

Still, there are gaps in our Christian lives that demonstrate an inability to transform loneliness into belonging. For example, before the coronavirus pandemic, almost a third of Christian households barely, if ever, practiced hospitality. Sixty percent had guests to their homes once a month, and only 39 percent had guests who weren’t family members. In an intimacy-starved society, shouldn’t Christians be open enough to have people over (when safe)?

We also don’t know what the longer-term effects of the pandemic will be on churchgoers’ loneliness. People often simply return to the state they are used to, even after a big event, a phenomenon known as the hedonic treadmill.

If, however, their routines have changed, so might their loneliness. Christians who stop going to church will find their loneliness affected, as well as their health. On the other hand, Christians who resume in-person church services and continue spending increased amounts of time with their families as they did during the pandemic might find their loneliness lower than before.

Something is working against the advantages practicing Christians have against loneliness: In-person time, singing, and more ought to give an obvious boost but don’t. And something seems to be giving practicing Christians resilience against loneliness, even when their churches are not meeting in person.

Although we don’t have all the answers to these questions, there are some clear steps that leaders in the church can take to protect against loneliness, whatever is going on. They can go on with the good traditions of Christian meetings, like singing, rallying around the work laid out for us in the Bible, and resisting the temptation to dilute meaningfulness.

What if the church took ministry for mental health, including loneliness, more seriously? What if churches spend at least the amount of energy addressing loneliness as they do getting meals to new parents? Loneliness is a less simple burden, but we are to carry one another’s burdens nevertheless.

We shouldn’t lose track of what’s actually at stake, though. If we aim only to reduce loneliness, we will miss. Loneliness is a gauge telling us about the state of our relationships. It is relationships we need to invest in when those we love feel lonely. Loneliness should prompt an investment of attention, naming and talking about loneliness as we aim at godliness, neighbor-love, hospitality, and peace.

Susan Mettes is an associate editor at Christianity Today. This essay is adapted from her forthcoming book, The Loneliness Epidemic. Copyright © 2021 Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group. Used by permission.