After touring the United States in the early 1830s, the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville concluded that “the organization and establishment of democracy among Christians is the great political problem of our time.”

We the Fallen People: The Founders and the Future of American Democracy

InterVarsity Press

304 pages

$18.89

Nearly two centuries later, the problem in the United States has evolved from establishing to sustaining democracy, but the underlying challenge for American Christians remains unchanged. As citizens of a democratic republic, we are called to think Christianly about democracy, respond rightly to it, and live faithfully within it. Among other things, this means figuring out what to make of the populist wave currently transforming American politics on the left and the right.

Before we can do so, however, we must first define what we mean by “populism,” and that turns out to be more complicated than you’d think. At first glance, the term seems so malleable as to be useless. Populism can appear among Democrats and Republicans, socialists as well as capitalists. Since 2016, the two best-known populists in the United States have been Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Think about that for a moment. What kind of phenomenon can bridge such a great divide?

All-consuming urgency

The answer begins to take shape once we shift our attention from policy to strategy. What unifies populism is its consistent rhetorical approach—its distinctive way of framing political issues, appealing to voters, and justifying the exercise of power once in office. Psychological research suggests that fact-based political arguments play a minuscule role in influencing the votes that we cast. The most persuasive political arguments come packaged as stories. They are narratives that help us to situate our lives, explaining who we are, what we should fear, and where our hope lies. To evaluate populism, we need to focus on the story that it tells.

The plot of the populist story is simple, unchanging, and melodramatic: Life consists of a perpetual struggle between “common people” and the elites who exploit them. The former are noble, virtuous, and righteous; the latter are corrupt, arrogant, and self-serving. The key to eradicating social ills and injustices lies in helping “the people” recognize their true enemies and mobilize to defeat them.

Within this basic template, it’s possible to plug in a broad range of specific details, sort of like a game of populist Mad Libs. Populists on the left often target greedy Wall Street financiers, “freeloading billionaires,” or an amorphous “corporate America” as the villains in the melodrama. Those on the right aim at Marxist intellectuals, Hollywood liberals, or the talking heads of the mainstream media.

Populists on both left and right condemn “Big Tech,” as well as the out-of-touch officeholders and bureaucrats of the “political establishment.” Significantly, both also tend to champion charismatic heroes, strong and “straight-talking” leaders who promise to obliterate business as usual.

Aspects of this story echo the typical appeals US politicians have been making for centuries. In democracy as Americans have known it since the early 1800s, vote-seekers routinely pay tribute to the wisdom of the people and impute moral authority to their preferences. They identify themselves as “outsiders” and denounce political corruption. They claim the mantle of the people’s champion, frame elections as “us versus them,” and warn that common folks will be worse off if the other side wins. Populism echoes each of these refrains.

What populist rhetoric adds to the mix is fear, outrage, and an all-consuming urgency. These traits aren’t incidental; they are indispensable. Populism—whether from the left or from the right—withers without them. Where they don’t arise naturally, they must be actively promoted, for a shared sense of grievance and affliction is what gives populism its distinctive emotional fervor.

At its most idealistic, democratic rhetoric has portrayed Americans as unified by a shared commitment to the principles enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. Seen in this light, our us-versus-them political battles may be messy and contentious, but they’re part of a principled struggle over how best to live out a common creed. Populism counters that our political opponents aren’t merely rivals; they are enemies. Far from sharing our principles, they hate what we love and despise what we cherish.

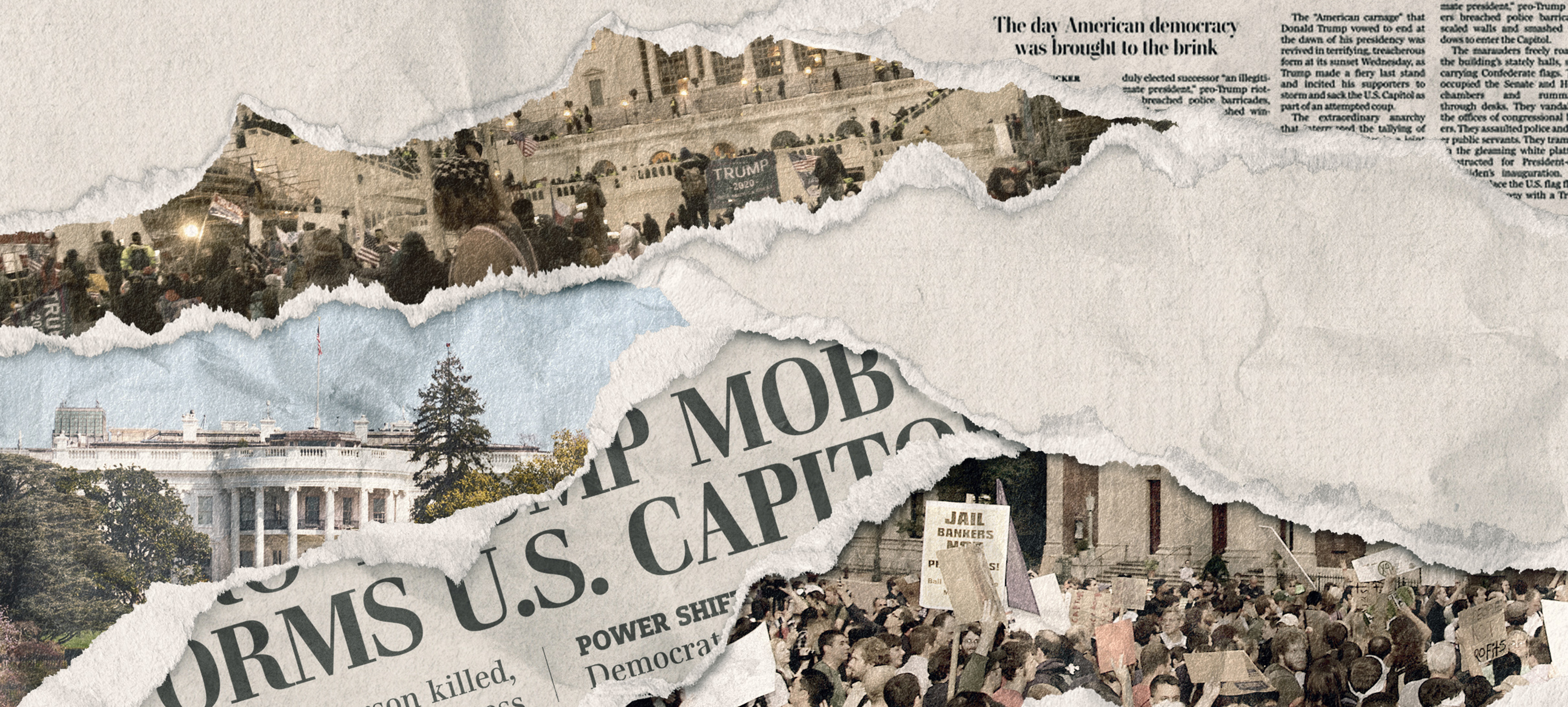

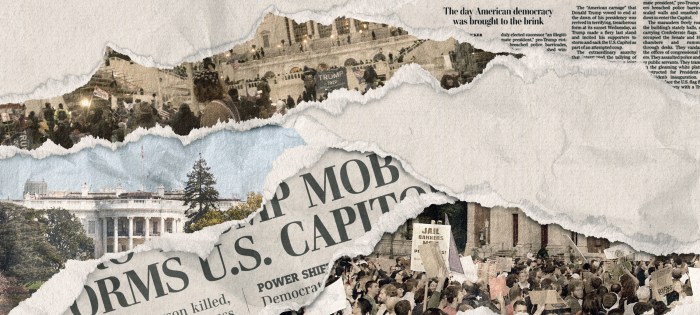

This assumption, in turn, transforms every national election into an Armageddon-like showdown, a “Flight 93” emergency (to borrow the framing from Michael Anton’s viral 2016 essay) in which we must storm the cockpit or die trying. Defeat, in this mindset, means the end of the country as we know it, an irreversible loss of freedom.

Disturbing tendencies

What should we think of the populist story? To the degree that Americans embrace it, how might it affect US democracy? To the degree that American Christians embrace it, how might it affect the purity of the gospel message and the witness of the church?

We’ll address each question in turn, but first a couple of caveats: There are some upsides to populist rhetoric, at least regarding its political consequences, and I can readily imagine why many Americans—on both sides of the partisan divide—might find populist rhetoric inspiring. Additionally, I don’t impugn the motives or question the sincerity of rank-and-file voters drawn to the populist message. My goal is not to rebuke but to exhort. We need to think more deeply.

Let’s begin with US democracy. The Bible teaches us to love our neighbors and to seek the peace and prosperity of our communities. What is the populist story teaching Americans about how to think and act politically?

On the plus side, populist rhetoric can often identify genuine social ills and highlight critical obstacles to national flourishing. It can motivate more citizens to pay attention to the public sphere, to educate themselves on the issues, and to hold their elected representatives accountable. These are essential traits for a healthy democracy, and without them self-government becomes little more than a figure of speech. And yet the quality of grass-roots activism is as important as its impact, and there are two tendencies in populist rhetoric that should particularly alarm us.

The first is its inclination to demonize and dehumanize opponents. As the story is commonly told, the political elites who oppose the populist agenda are evil—racist bigots or socialist radicals equally determined to destroy our liberties. The rank and file of voters who agree with them aren’t necessarily malevolent, but neither are they citizens of “the real America.”

Since populism extols the wisdom and virtue of ordinary people, populist logic dictates that those who oppose the movement can’t truly be a part of the people. When populist leaders invoke “the people,” then, who they really have in mind are the folks who agree with them. Everyone else is an enemy. This divides the political universe into two groups—nothing new there—but it goes on to insist that only one of those groups deserves a voice. Taken to this extreme, the message of populism becomes fundamentally incompatible with an open, pluralistic society.

The second disturbing tendency is a penchant for catastrophizing the consequences of defeat at the polls. This doesn’t just magnify our animosity toward the other side. The greater danger is that it will gradually erode our commitment to the rule of law and increase our tolerance for authoritarian solutions to the “existential threat” that we face. If everything we hold dear is really at stake, the argument for dispensing with constitutional procedures can’t help but gain force.

For several years now, opinion polls have found that a fourth to a third of Americans are open to accepting a political system that features “a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress or elections.” Just this summer, a survey of the Public Religion Research Institute found that 15 percent of respondents (including 28 percent of Republicans) agreed with the statement that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” What is this but the logical outworking of the populist message?

In sum, to the degree that we internalize the populist story, we are likely to have less patience with complicated solutions, less motivation for constructive engagement with other perspectives, less openness to compromise across the aisle, less space for genuine pluralism, and less willingness to submit peacefully to electoral defeat. In the process, we will find ourselves more prone to intolerance and more accepting of authoritarianism.

To the extent that we are shaped by the populist promise, the long-term threat to democracy is dire. But its long-term impact on the church and its witness may be worse.

Heightened fear and misplaced hope

Blatantly, if unconsciously, the populist story undercuts two pillars of historic Christian orthodoxy. The first is the doctrine of original sin, the understanding that we all enter the world as natural rebels against our rightful ruler. The second is the concept of imago Dei, the doctrine that each of us bears the image of God, a status that confers equal dignity on us all.

These truths offer a vivid reminder, in the words of Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, that “the line separating good and evil” never falls neatly between political parties or movements. It passes instead “through every human heart.”

Populist rhetoric, in contrast, implies that the dangers that assail us lie wholly outside of us. Evil is real, but it resides only in our enemies. In practice, the us-versus-them populist story denies original sin in us and God’s image in them. In the process, it teaches that our most pressing problems can be solved while leaving our hearts unchanged.

Our nation’s first populist president, Andrew Jackson, set the mold for such rhetoric two centuries ago. Old Hickory assured his followers that they were “uncorrupted and incorruptible” and “renowned for their high tone of moral character.” But his fellow countrymen who opposed his agenda were “vile,” “wicked,” “cowardly,” “sordid,” and “despicable.” Jackson further warned the people that their liberty was in danger, accused much of official Washington of accepting bribes, and implied that without him the people’s cause was hopeless.

More recently, we listened as our nation’s second populist president, Donald Trump, echoed the same themes. Trump praised his followers as “good and virtuous people” and denounced his political opponents as (among other things) “cowards,” “human scum,” and “bad people” who “hate our country.” Lamenting that “traitors” in Washington were bent on destroying America, Trump ridiculed the corruption and incompetence of the federal government and echoed Jackson by proclaiming, “I alone can fix it.”

Strip away the verbal abuse, and the underlying message of both presidents remains quintessentially populist: An innately great people is being betrayed by evil enemies in their midst. The institutions of government can no longer be trusted. The only solution is to fall in line behind the people’s champion, a strongman who pledges to be their deliverer.

We would rise up in righteous anger to condemn a politician who made sure to insist in every speech that “God is dead,” or “Christianity is a myth,” or “religious faith is a crutch for the weak and feeble-minded.” Why would we cheer when a public figure proclaims that we are good, they are evil, and our only hope is in him? Aren’t such claims just as corrosive to Christian truth? Aren’t they just as antithetical to the gospel?

We should also be leery of populism’s do-or-die narrative of impending catastrophe: It is tailor-made to resonate with—and politically exploit—the fear that plagues so many white evangelicals today. Historian John Fea has written persuasively about what happens to our public witness when fear of man overshadows hope in God. To conservative Christians who understandably lament the rapid secularization of American culture, the populist message too often leads to heightened fear and misplaced hope.

We should hear alarm bells any time a politician promises to help Christians “take our country back.” Embedded in such promises is a proposal to exchange cultural power for political support. The price of such transactions is high. Democratic candidates have largely given up on appealing for white evangelical support on any basis, but Republican politicians frequently make such tempting offers.

Not surprisingly, Trump has been among the most explicit in defining the terms of the transaction. In an interview with the Christian Broadcasting Network early in the 2016 campaign, Trump introduced a theme that he would return to repeatedly: “Christians in our country are not treated properly,” he lamented. “I want to give power back to the church because the church has to have more power.” As he told an evangelical audience prior to the Iowa caucuses, a Trump presidency would mean “Christianity will have power … You’re going to have plenty of power. You don’t need anybody else.”

Christianity will have power … You don’t need anybody else. To say these words and believe them is the height of hubris. To hear these words and believe them is the epitome of idolatry.

Rhetorical Trojan horses

If this sounds like a jeremiad, it is. I’m not remotely suggesting that populism is intrinsically an enemy of democracy, nor do I think for a moment that voters who are drawn to populist candidates intentionally seek its downfall.

But as a historian of the United States, I am convinced of two truths: Democracy is fragile, and many of the most important developments in our past have been unintended rather than premeditated. There are tendencies in the populist message that, however seductive, have the potential to weaken American democracy by subtly eroding Americans’ commitment to it. It’s entirely possible for us to undermine democracy while believing we are working to preserve it.

Nor am I arguing that populist rhetoric is always at odds with Christian truth, much less that Christians who endorse populist rhetoric are invariably guilty of sin. But I do know that zeal without discernment is not a virtue (Rom. 10:2). There are tendencies in populist rhetoric that we must resist. Too often the populist story misleads us about who we are and where our hope lies, which is another way of saying that populist rhetoric is prone to declaring a false gospel and proclaiming a false god. A fallen world is listening. The danger is that the church is listening as well.

So what are we to do? How are we to respond? It’s unlikely that populism will go away anytime soon. It’s shown far too much appeal for that. As long as voters reward them, more than enough office-seekers will be willing to proclaim the populist message that our “itching ears” are happy to hear: We are virtuous, they are evil, and all social ills can be remedied while leaving our hearts untouched. But even as the populist message persists, we can resolve not to affirm it unconditionally, and we can actively resist allowing it to shape our hearts and redefine our faith.

This will require at least two things of us. First, we must revitalize our appreciation of the foundational Christian truths that populism contradicts. We need to feel afresh the weight of original sin and remind ourselves daily that, just as it marks each of us individually, it also leaves its imprint on every political institution we revere, every political party we champion, every incumbent we cheer, every candidate we vote for.

Similarly, we must marvel anew at the miracle of imago Dei, perpetually remembering with C. S. Lewis that there is no such thing as a “mere mortal,” that even our most bitter political opponents are fearfully and wonderfully made in the image of the God who loves them and gave his own Son for them.

Our second task, already implied, is that we must begin to take political rhetoric more seriously. In recent years, evangelical political engagement has been defined by a worldly pragmatism that emphasizes ends above means. “Actions speak louder than words,” we say, and if candidates agree with us on important issues, isn’t that what counts? As a prominent conservative columnist advised on the eve of the 2020 election, just evaluate the candidates “with the sound off.”

Of course, Christians are supposed to frown when our favorite politicians engage in “locker-room talk” or take the Lord’s name in vain, but apart from such transgressions, why should we care how they frame the issues as long as they’re on our side and seem likely to deliver results?

This is a tragic misunderstanding of the power of speech, and we need to renounce it. I’m not primarily suggesting that we heighten our sensitivity to vulgarity and profanity in the public square, although that might not be a bad thing. What I’m recommending is biblically informed scrutiny of the stories that our leaders tell us while they’re soliciting our votes. They are verbal Trojan horses, crammed with heart-shaping assumptions that we ignore at our peril. Even as candidates promote policies we hold dear, they may be framing their arguments with narratives at war with the gospel we proclaim.

Robert Tracy McKenzie is a professor of history and holds the Arthur F. Holmes Chair of Faith and Learning at Wheaton College. This article is adapted from his book We the Fallen People: The Founders and the Future of American Democracy.