The American mosque increasingly resembles the American church.

New data released in the US Mosque Survey 2020 reveals a plateau of conversions, a shift to the suburbs, and a challenge with “unmosqued” youth.

“Muslims and their mosques are becoming more integrated into American society,” said Ihsan Bagby, the lead investigator, “and more adjusted to the American environment.”

Released every 10 years, the survey aims to comprehensively dispel misconceptions about the locus of Muslim community in the United States.

How might the findings guide American evangelicals?

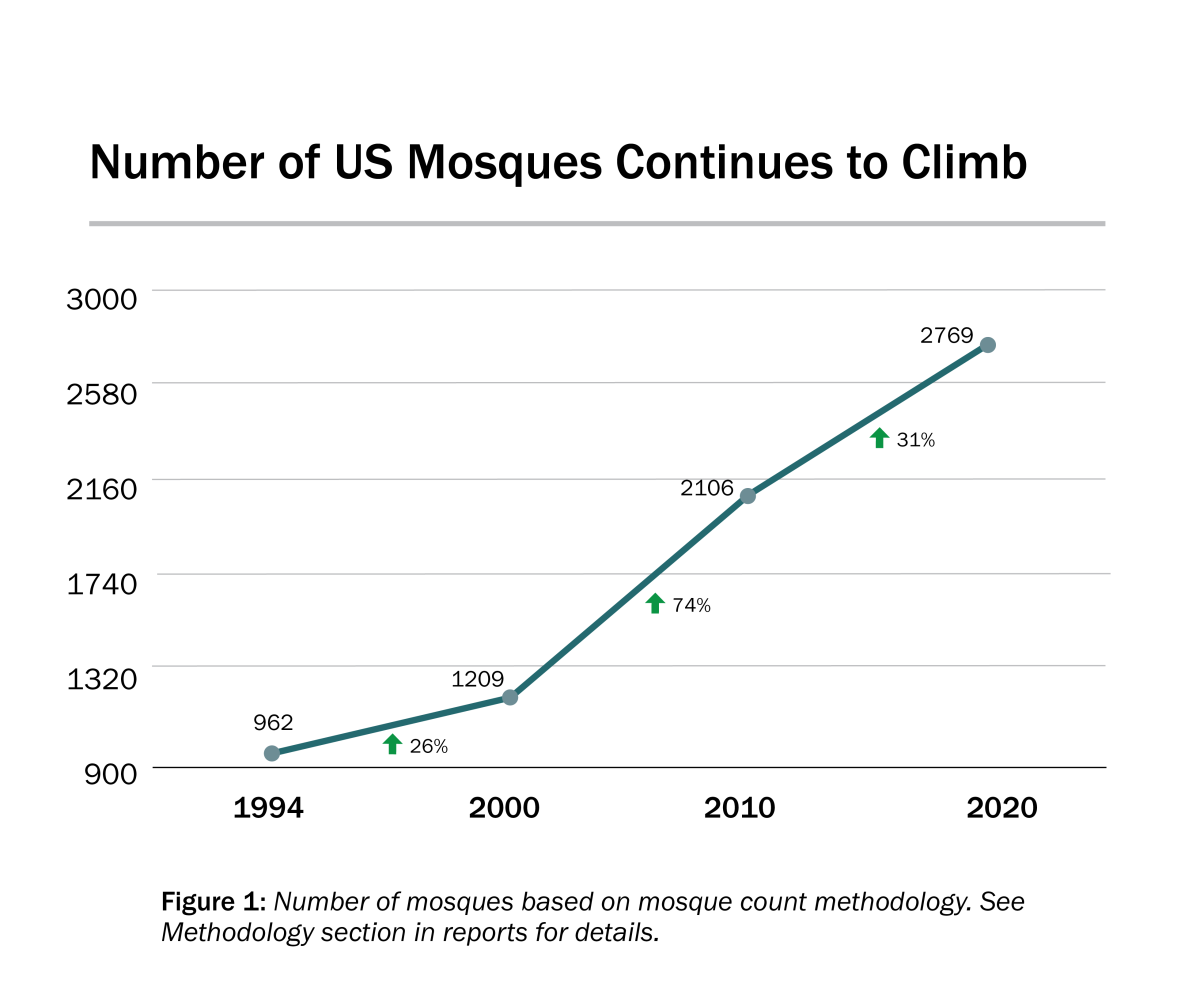

Begin with the contrast: an increase in the number of new mosques—the Muslim equivalent to church planting.

The survey counts 2,769 mosques in the United States, an increase of 31 percent since the 2010 report. The prior decade had a growth rate of 74 percent, from 1,209 mosques counted in the 2000 report to 2,106 in 2010.

The survey also shows that Muslims increasingly appreciate the suburbs.

The share of mosques in the downtown areas of large cities has dropped from 17 percent in 2010 to 6 percent in 2020, while the share in small towns has dropped from 20 percent to 6 percent. The survey found that 8 in 10 Muslims now live in a residential or suburban area.

“As we begin to share the same neighborhood, engaging the Muslim community is no longer just the domain of missionary specialists,” said Mike Urton, the associate director of Immigrant Mission, a ministry of the Evangelical Free Church of America.

“It is now the domain of the local church.”

Muslims also “tithe” similarly to their Christian neighbors.

Including contributions toward operating expenses and the obligatory zakat charitable giving to the poor, the survey calculated average mosque income to be $317,140, compared to a calculated average church income of $311,782.

Many Muslims are doctors and teachers, said Kevin Singer, codirector of Neighborly Faith. And many contribute to the good of their society. He noted the effort of a South Carolina Muslim youth group to provide groceries for medical shut-ins during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There is a real eagerness,” Singer said, “to make a positive, demonstrable impact.”

And just like evangelicals, Muslims experience the “strangeness” of a secular culture. While many youth are engaged, others keep their distance from the practice of faith.

Noting separate data by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), the new survey establishes that the US Muslim population is young, with 54 percent aged 18–34. But in terms of mosque attendance, this age bracket represents only 24 percent of the total.

Bagby said it is well known within American mosques that this age segment is difficult to integrate into congregational life. He just hopes the data keeps Muslims from being complacent.

(The survey notes the share of US church attendees aged 18–34 is 11 percent.)

Urton believes first-generation Muslim immigrants represent an “amazing opportunity.” Since they are still connected with relatives and friends in their countries of origin, Christians who reach out to them in friendship also communicate Christ’s love to the other side of the world.

But it is easier to reach the second generation in the US.

“With English as their first language and their familiarity with sports and pop culture,” Urton said, “common ground is available, and relationships easier to initiate.”

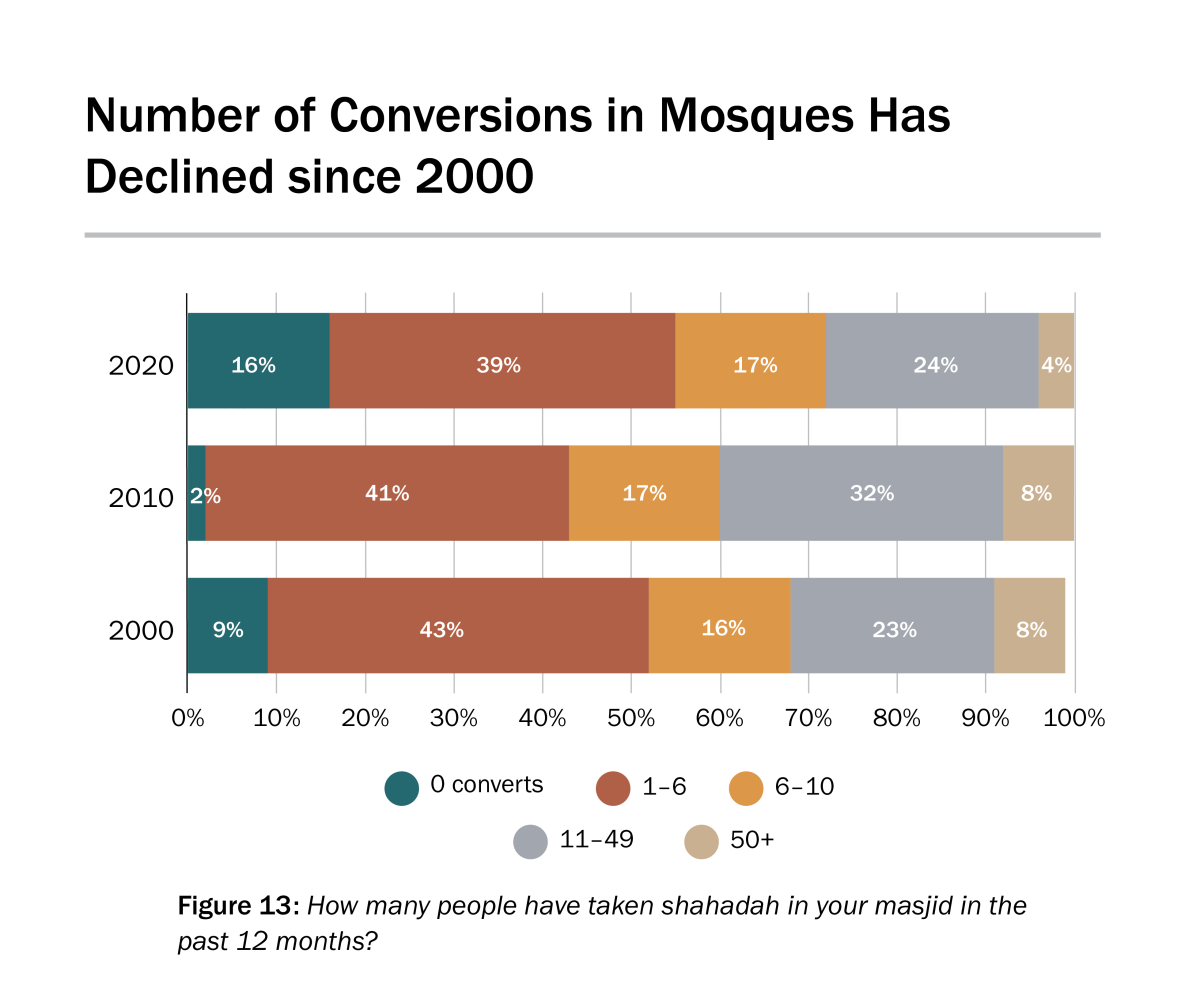

Of course, common ground goes both ways. The survey found a Muslim convert population of 31,290.

However, conversions are plateauing, and the survey sponsors attribute the growth in the number of mosques to immigration and birth rates. Converts now make up 11 percent of mosque attendees, compared to 15 percent in 2010 and 16 percent in 2000. The overall tally of converts declined roughly 2,000 individuals.

No conversions were reported in 16 percent of mosques. In 2010, this was true of only 2 percent.

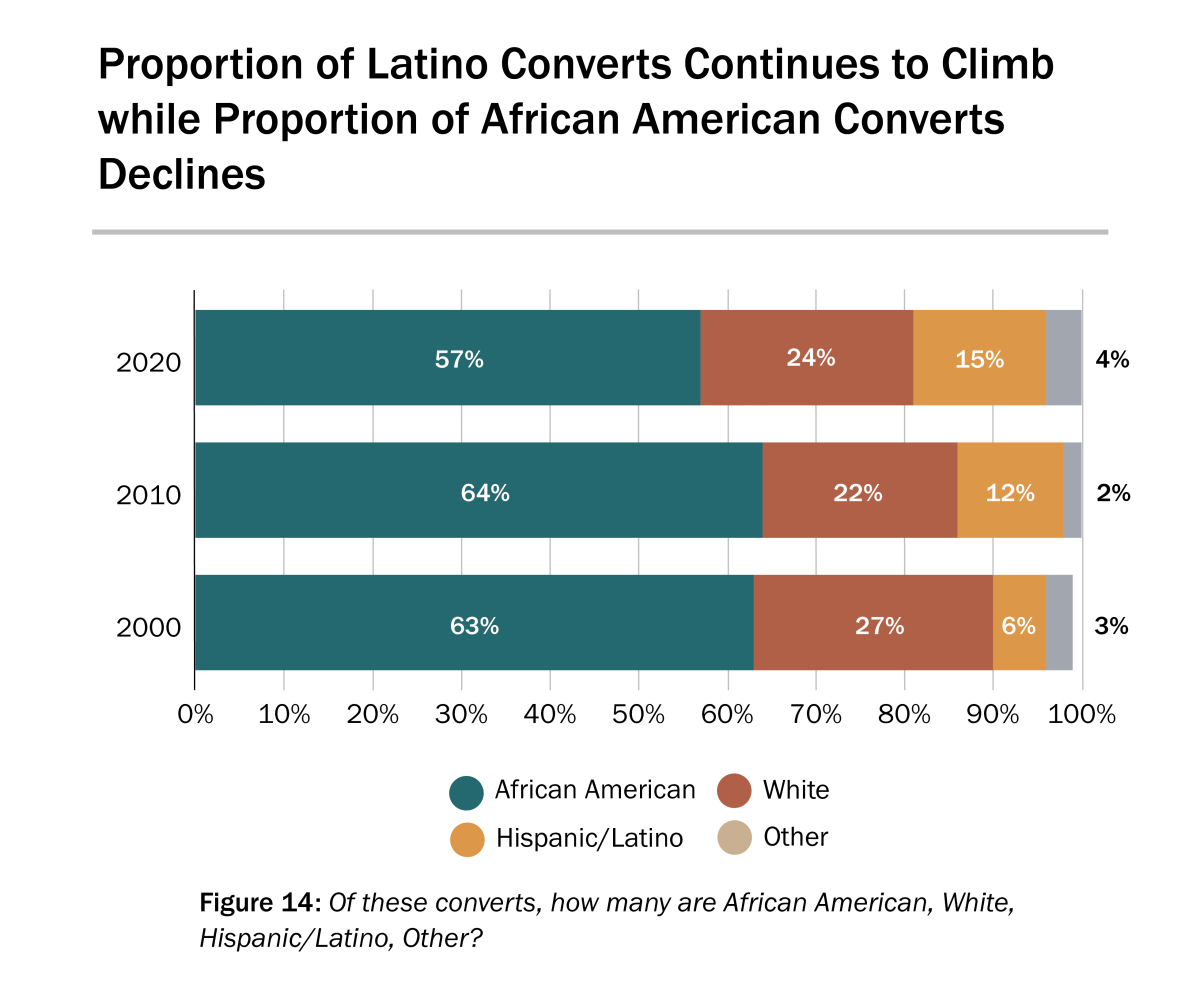

Looking more closely, the survey suggests this is tied to the plateauing of African American Islam. In 2010, such mosques constituted 23 percent of the total and 24 percent of individual attendees. But by 2020, other ethnicities had surged, leaving African American mosques at 13 percent of the total and their attendees at 16 percent. This population is aging, said the survey, noting most conversions took place in the 1960s and ’70s.

Damon Richardson, founder of UrbanLogia Ministries, recalled W. E. B. Dubois’s “double consciousness” to interpret the data.

“As Black and as an American, there is a constant sense of having to always look at oneself through the lens of others,” he said. “Perhaps now a triple consciousness—adding Muslim—has taken a significant toll.”

As white Americans increasingly racialized Islam, stereotyping it as dangerous and radical, any African Americans contemplating conversion would need to consider another social barrier, he said.

But the response of the Black church has also made an impact. Richardson grew up in the Nation of Islam until becoming a Christian at age 16. His apologetics ministry addresses the attraction of alternative spirituality to those suffering ethnic identity and socioeconomic issues.

This attraction exists among Hispanic Americans also.

In the 2010 survey, Latino converts to Islam represented 6 percent of total converts. In 2020, they increased to 15 percent.

“Millions of spiritually oriented Hispanics are disillusioned with their historical Catholic roots,” said K. R. Green, director of catalytic movements for PLAN panta ta Ethne (named for the Greek phrase often translated as “all nations” in the New Testament). “Muslims then speak of Islam as ‘a return to Latino roots’—that is, the 800-year Moorish rule of Spain.”

Since 1990, first from Colombia and now from Houston, Green has mobilized Latin Americans to be missionaries to the Islamic world. Working with refugees, he finds Muslims are also increasingly disillusioned with their faith, while ethnic and linguistic similarities make Latinos especially effective at relating the gospel to them.

“What God is doing to mobilize Hispanics for gospel work is staggering,” said Green. “He has endowed them to reach the last of the unreached peoples of the world.”

Richardson just hopes white Americans don’t get in the way.

“Muslims in the US tend to view Christianity as ‘the white man’s religion,’” he said. “While world missions has effectively come to our doorsteps, the credibility of the Christian witness has significantly diminished as evangelicals have become more politicized and nationalistic.”

The American mosque, meanwhile, is multicultural. Only 4 percent are composed of a single ethnicity or nationality (defined in the survey as 90 percent of attendees); however, 3 out of 4 do have one ethnic group that “dominates the mosque.” Overall, 39 percent of American Muslims are South Asian, 28 percent are Arab, 16 percent are African American, 8 percent are African, and 9 percent are other ethnicities (such as Turkish and Iranian).

Other data in the new survey—sponsored by the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), the Center on Muslim Philanthropy, and ISPU and conducted in conjunction with Faith Communities Today research— shows how mosques are institutionalizing in the US.

Though only half of US mosques employ a full-time imam, this has increased from 43 percent in 2010, showing evolution toward standard religious practice in American churches. Traditionally within Islam, the imam only conducts prayer and gives a sermon, while the mosque is a gathering place without religious authority.

And as mosques have institutionalized in the US, authority is shifting to a board. The imam is now the “leader” of only 30 percent of US mosques, down from 54 percent in 2010.

Paid imams, however, are increasingly American. While only 22 percent are US-born, this is an increase from 15 percent in 2010. Overall, 32 percent of imams were born in the US, with 47 percent of these being African American. (ISPU notes that 51 percent of US Muslims were born outside the US.)

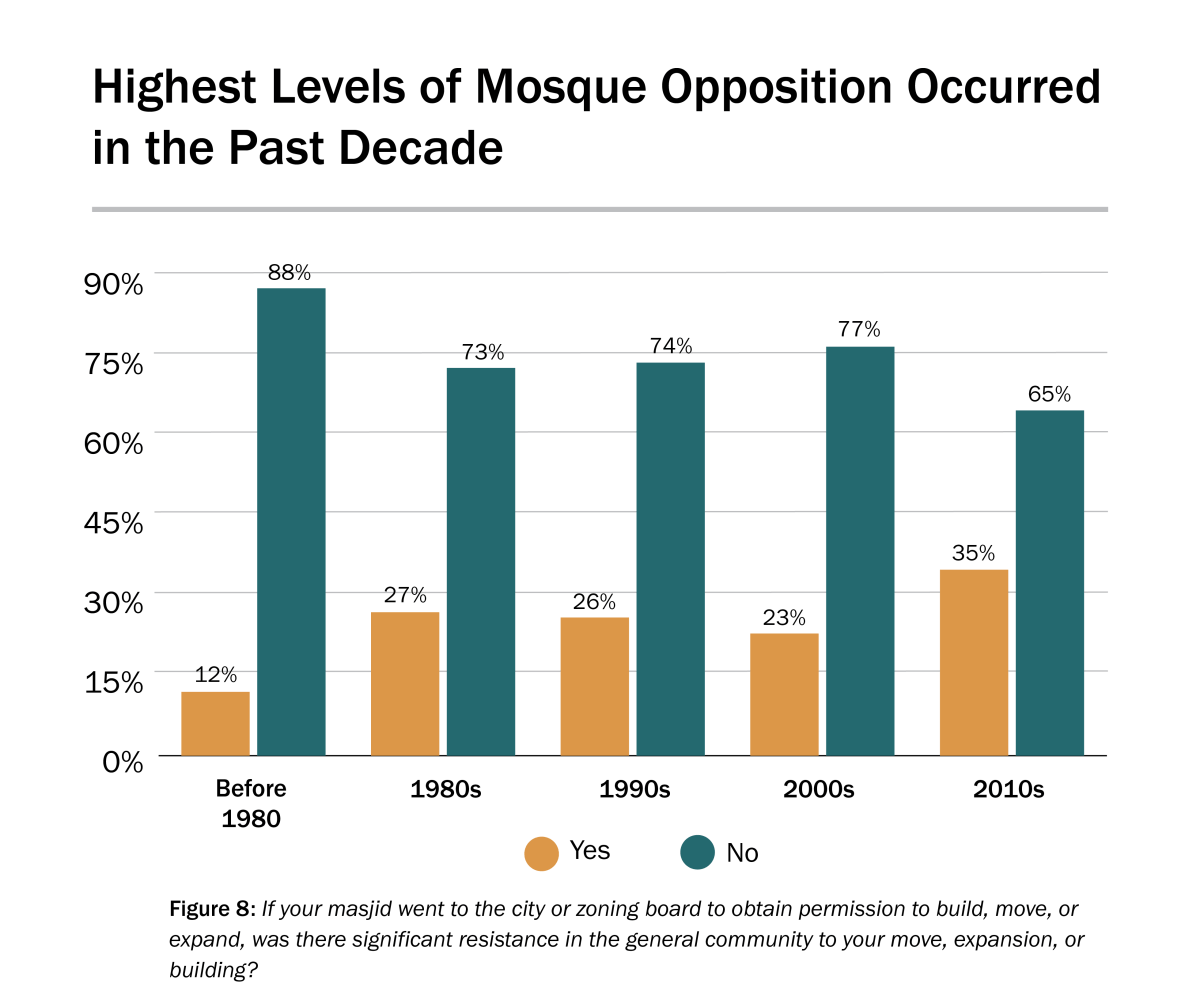

But as US Muslim communities increasingly resemble America, they are finding more localized resistance. A new question in the 2020 survey revealed that over the past 40 years, 28 percent of mosques faced “significant resistance” when they sought zoning board permission to build, move, or expand their houses of worship.

In the last decade, it increased to 35 percent.

“Our communities are just as much theirs, though evangelical Christians typically have more influence,” said Singer. “We can make a significant difference to ensure Muslim communities are welcome and safe and even be generous toward their families.”

Bagby linked opposition to mosques to Islamophobic political rhetoric, saying that increased societal interaction tends to lead to greater acceptance. Volume 2 of the survey, to be released in July, will demonstrate how mosque-based Muslims are involved in political, social, and interfaith activities.

“The Muslim community is laying down roots in the United States and is here to stay,” said Urton.

Some evangelicals view this as a “bad thing,” said Singer. Instead, they should remember the biblical injunctions to walk in faith, not fear, as they seek to live peaceably with all.

“New mosques in our communities give us an opportunity to practice these teachings,” he said, “and, most importantly, to share and demonstrate the love of Christ.”