Earl “DMX” Simmons kept it real whether he was testifying about his angels or his demons.

While it’s common for grief, depression, anxiety, and faith to come up in popular music today, Simmons rose to fame at a time when hip-hop songs about flashy cars, jewelry, and expensive clothes ruled the charts. The rapper best known by his stage name DMX shot videos in his childhood neighborhood wearing workman’s jumpsuits and few gold chains.

Simmons—who died last week at age 50—is the first and only rapper to have five albums debut at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart, and he did so while making Christianity a central element of his music. DMX’s witness over his 30-year career reshaped how the genre engages faith in public.

“Before DMX, black R&B artists would generally wear a cross, briefly mention they were reared in the black church in their youth, or thank Jesus for their success during award shows,” said Cassandra Chaney, a professor at Louisiana State University who researched how rappers discuss heaven in their music. “When DMX came on the scene, he showed the world that they could and should have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.”

Simmons grew up in the projects of Yonkers, New York, the only son of a teenage mother. Raised a Jehovah’s Witness, his favorite childhood book was a Jehovah’s Witness children’s Bible. But Simmons wrote in his autobiography that he left the Witnesses when his mother declined an insurance settlement after he was hit by a car as a child, citing a religious belief against accepting charity.

Simmons had a troubled childhood. His father abandoned the family. His mother was abusive and sent him to a children’s home. He was first arrested at age 10. But he found solace in the arms of his grandmother. In “I Miss You,” Simmons celebrates her influence: “I thank you for my life / I thank you for my Bible / I thank you for the song that you sang in the morning ‘Amazing Grace.’”

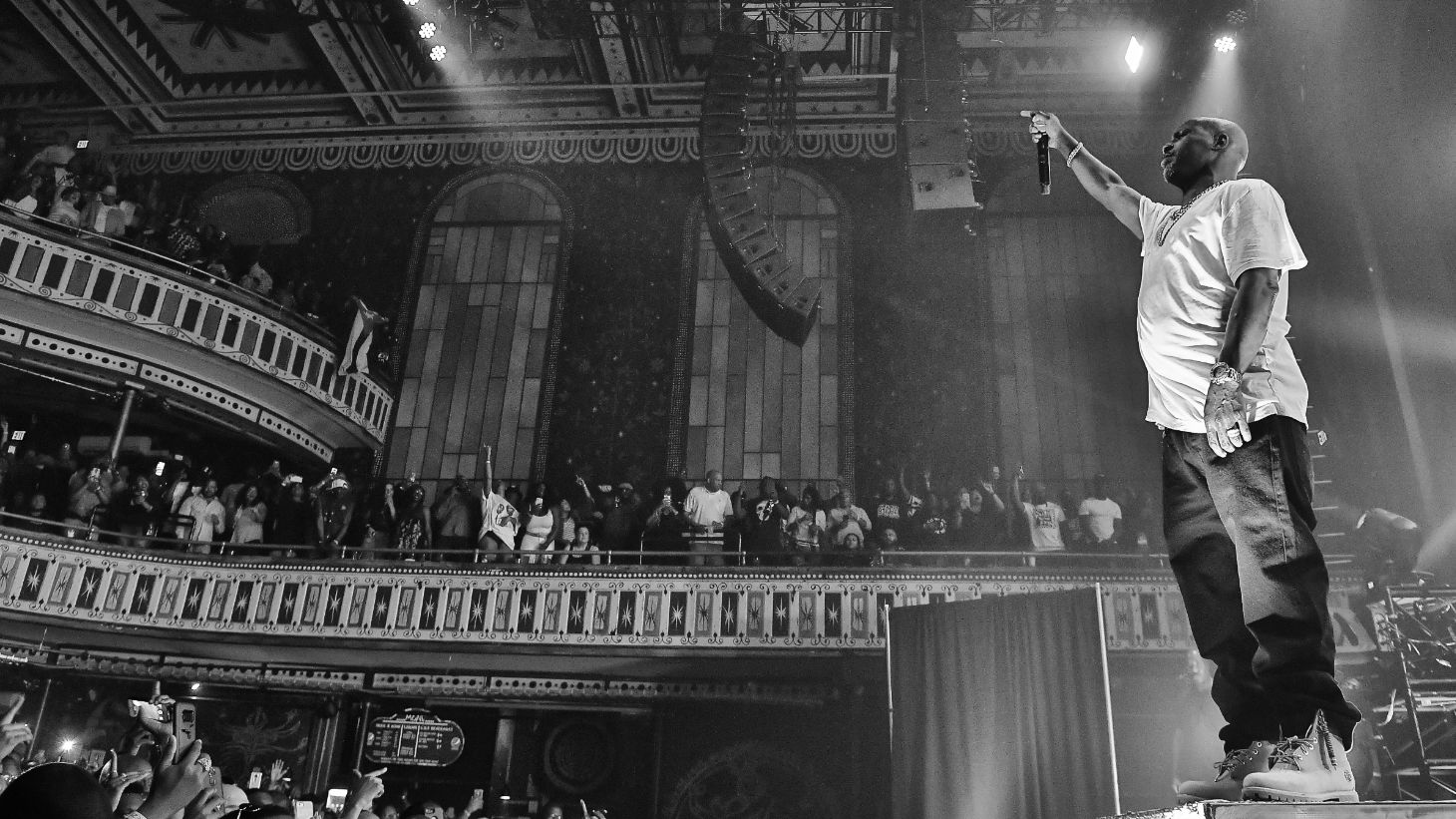

Despite his difficult upbringing, Simmons would become a multiplatinum artist and grow deeper in his Christian faith. In one of his Instagram Bible studies last summer, he called “every album a prayer.” He had a habit of concluding both his albums and concerts with prayer.

“I grew up in church right outside Yonkers and always struggled with it not being cool to pray or talk about Jesus near friends,” said Jordan Rice, pastor of Renaissance Church in NYC. “I’ll never forget at the end of Summer Jam in ’98 or ’99 where DMX closed out his set with a prayer. He was crying, and so were thousands of people in the audience. That honestly emboldened me to say that I was a Christian.”

Simmons died April 9, after spending more than a week on life support following a heart attack. In both his life and his tragic death, he challenges the notion that Christianity leads to a life free of trouble. Simmons struggled openly with substance abuse, after having been tricked into smoking crack for the first time at 14 by a friend and mentor. He was arrested multiple times and served several prison sentences for offenses ranging from tax evasion to assault.

Simmons battled his demons just as publicly as he fought for his better angels to prevail. His song “Angel” begins with a paraphrase of Mark 8:36: “What good is it for a man to gain the world / Yet lose his own soul in the process?” He then raps, “I’m callin’ out to you, Lord, because I need your help / See, once again I’m havin’ difficulty savin’ myself / Behavin’ myself, you told me what to do, and I do it / But every and now and then it gets a little harder to go through it.”

Simmons was an ordained deacon at Morning Star Baptist Church, the church he attended while living in Arizona. He told GQ in an interview in 2019 that he had read the Bible completely three times, and in the same year he led prayers at Kanye West’s Sunday Service.

Alejandro Nava, author of In Search of Soul: Hip-Hop, Literature, and Religion, said Simmons’s “unabashed willingness to bare his sins and soul to the world” made him unique. “Unlike most gangster rappers, who almost always put on masks of machismo and hardness, DMX revealed to the world the crippling burdens and struggles eating away at his psyche,” said Nava, a professor at the University of Arizona.

In the hit song “Slippin,” he brings up drugs, prison sentences, abuse, and abandonment: “ I’m slippin’ I’m fallin’ I can’t get up / Ay yo I’m slippin’ I’m fallin’ I can’t get up / Ay yo I’m slippin’ I’m fallin’ I gots to get up / Get me back on my feet so I can tear s— up.”

This song reflects the message of another popular early ’00s song by gospel artist Donnie McClurkin, “We Fall Down.” McClurkin sings, “We fall down / But we get up / For a saint / Is just a sinner who fell down / But we couldn’t stay there / And got up.”

It can be hard to look at the life of someone who struggled so publicly to stay sober and out of prison, and see the hand of God in their life. Many Christians believe—or at least hope—that once saved, life goes perfectly, our demons are excised, and we are only tempted toward minor sins we can privately confess in our quiet times.

Rice, the pastor and fellow Yonkers native, emphasizes grace in the story of an artist who kept turning to God in his struggle.

“In practice, all of us can identify with the disappointment of living beneath what a holy God requires from us,” he said. Simmons’s “life and tragic death highlight, not extinguish, for me the nature of grace. Undeserving people get unearned benefits by an unobligated giver.”

The gospel is not some magic formula for the perfect life, as Paul attests, and some of us will fail spectacularly. But the good news is that Jesus will always meet us in the pit.

“It’s important to recognize that the men and women of the Bible that we like to put on pedestals were pretty messy people,” said Nicola Menzie, founder and editor of Faithfully Magazine. “Their testimonies, and [Simmons]’s testimony, show that there is room in the presence of God for all of us. God sees us exactly as we are and His love doesn’t fade— whether we’re at our best or at our lowest moments.”

Simmons represents a different kind of testimony, but one the church needs to hear.

“His faith in God, however, was a constant reminder that there was love in the world, and that love could be more powerful than the forces of violence and death,” said Nava, who referenced how DMX addressed this tension explicitly in his music. His song “The Convo,” from the 1998 album It’s Dark and Hell is Hot, “describes the voice of God as exhorting him to choose life over death, poetry over guns: ‘No,’ God says, ‘Put down the guns and write a new rhyme.’”

Robert Tinajero, an English professor specializing in the rhetoric of rap at the University of North Texas – Dallas, referenced another track from that album, “Prayer,” where Simmons prays, “I come to you hungry and tired, you give food and let me sleep / I come to you weak, you give me strength and that’s deep / So if it takes for me to suffer, for my brother to see that light / Give me pain till I die, but please Lord treat him right.”

“Like a number of rappers (and people in general), [Simmons] seemed to struggle between living a godly life and living a life of vice and indulgence,” Tinajero said. “His lyrics could be quite violent and misogynistic, but he also had a caring and spiritual side to him.”

In addition to preaching and reading Scripture on social media, he also took to the pulpit after his ordination as a deacon. A 2015 sermon was recently posted online, showing Simmons speaking of God as a God of second chances and bringing up his desire for God to remove his impulse to do drugs. He talked about breaking sinful patterns: “Being born again, that’s the first step, and the second step is to stay in that Word.”

Sharing the love of God with others was part of Simmons’s testimony both on and off the stage. In the aftermath of his death, several stories went viral on social media about his kindness and generosity to regular people he encountered on airplanes and in the streets of Mt. Vernon, New York. Nava says that is one of the biggest takeaways from Simmons’s life that reflects one of the fundamental messages of Jesus’ life.

Simmons shared Jesus’ devotion “to the poor and outcast of the projects, ghettos, and barrios of the world. … Those he called his ‘dogs’ essentially meant the disenfranchised individuals and groups of society, those whom society treats like animals or lepers, those whom Jesus cherished above all,” he said.

Through his life and lyrics, Simmons invites us to reconsider our own relationships with those who are suffering or marginalized. In his song “I’ma Bang,” Simmons raps, “I speak for the meek and the lonely, weak and hungry / Speak for the part of the street that keep it ugly.”

Despite Simmons’s exceptional career and fame, his story also brings up systemic issues that affect millions in our country: poverty, the availably and quality of affordable housing, abuse, and the brokenness of the criminal justice system.

Chicago pastor Jonathan Brooks says Simmons’s life reminds us that “we all live in complex neighborhoods full of complex people and complex structural issues. Therefore, our understanding of how the gospel message is actually understood and applied there will also be complex.”

In Romans 7, we meet Paul at war with himself, lamenting the good he desires but seems unable to do. Earl Simmons, the rapper known as DMX, understood Paul’s internal battle. His willingness to speak and rap about that struggle gave contemporary language for every Christian who has a heart to follow God, but must continually fight temptation or substance abuse.

Just as the grace of God was available to Paul, it was also available to Earl “DMX” Simmons.

Kathryn Freeman is an attorney and former director of public policy for the Texas Baptist Christian Life Commission. Currently, she is a master of divinity student at Baylor University’s Truett Seminary and one half of the podcast Melanated Faith.